- Home

- Our Stories

- Negro Leagues stars served with honor during WWI

Negro Leagues stars served with honor during WWI

On Nov. 11, 1918, the “war to end all wars” came to an end when Germany and the Allied Forces reached an armistice. The Treaty of Versailles wasn’t signed for another seven months, but for years afterward that momentous fall day was memorialized around the world.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

It became officially known as Armistice Day in 1926, and a Congressional resolution in 1938 made it a national holiday. After World War II, the name was changed to Veterans Day, in recognition of all who served their country.

In the hallowed halls of Cooperstown, 68 bronze plaques are accompanied by bronze medallions, denoting the Hall of Famers who have defended their country during times of war. Of those 68, 27 were veterans of The Great War, and four of them served and fought for their country despite enduring prejudice and injustices at home in the United States due to the color of their skin.

Those four were Oscar Charleston, Bullet Rogan, Louis Santop and Jud Wilson – all of whom had retired or passed away before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947. Charleston, Rogan and Wilson served in the U.S. Army, while Santop was a member of the U.S. Navy, and all but Charleston saw their professional careers disrupted by their military service.

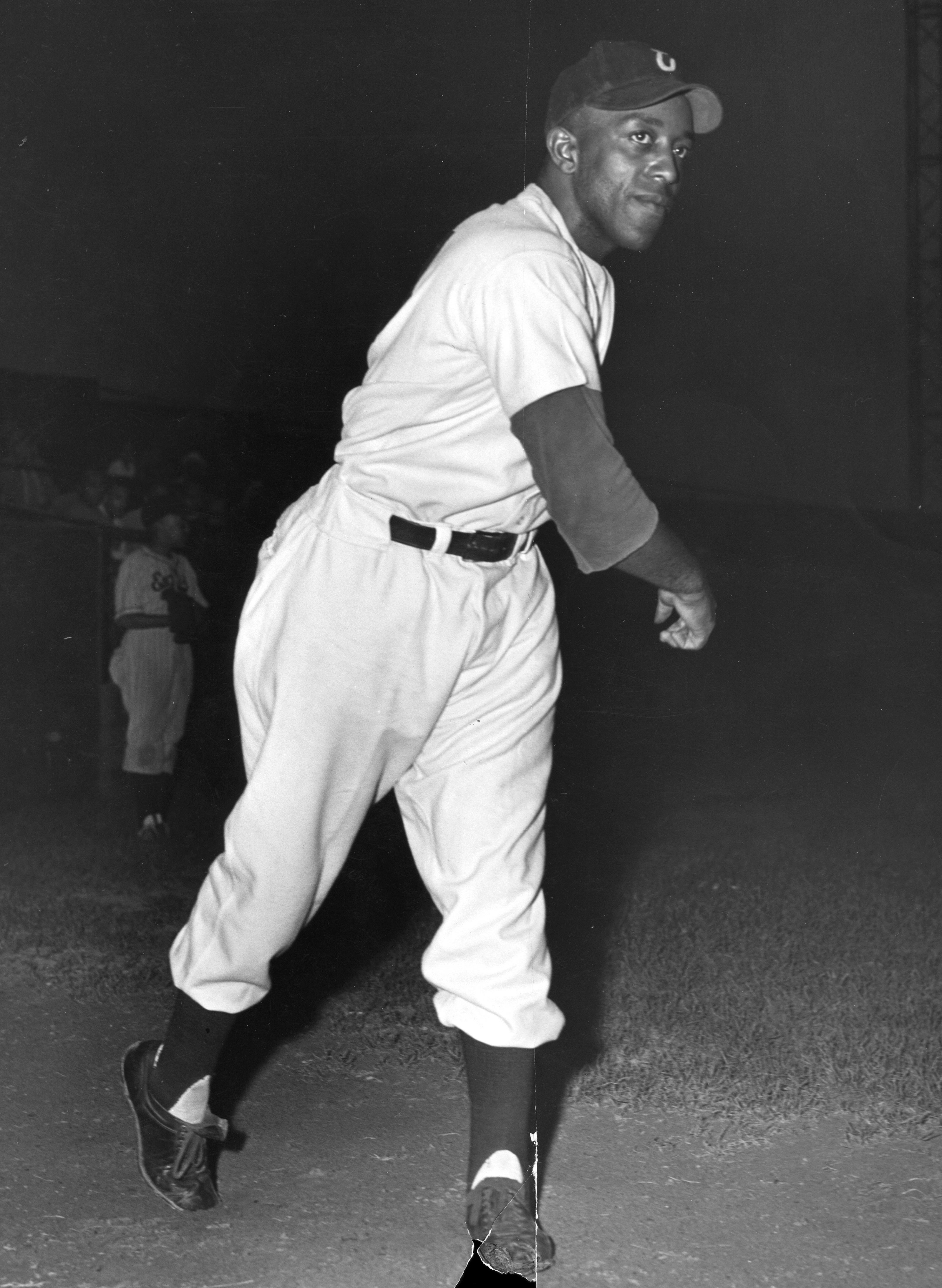

For Charleston, it would have been difficult for his professional career to be interrupted, because by the start of World War I the talented outfielder and manager’s career had not even begun. A batboy for the Indianapolis ABCs, Charleston lied about his age in 1912 and enlisted in the Army at just 15. He was assigned the Twenty-Fourth Infantry, Company B, one of the original Buffalo Soldier regiments: All-Black regiments formed in 1866 after the passing of the Army Organization Act. Shortly after enlisting, Charleston shipped out to the Philippines, where he served until 1915.

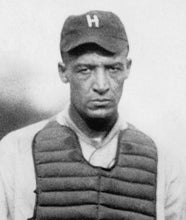

While on duty overseas, Charleston played on the regiment’s baseball team alongside fellow future Hall of Famer Charles Wilber Rogan, better known as “Bullet” or “Bullet Joe,” where they helped establish the 24th as a force to be reckoned with on the diamond.

Upon the end of Charleston’s tour of duty he returned to the states and the Indianapolis ABCs, this time as a player rather than a batboy, and embarked on a professional baseball career that lasted until his death in 1954.

Rogan was honorably discharged in 1914, but chose to reenlist, this time with the 25th Infantry – another Buffalo Soldier regiment stationed at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii and later at Fort Stephen Little in Arizona. It was there that he joined the 25th Infantry Wreckers who, at their peak during Rogan’s tenure there from 1914-1918, are now regarded as one of the finest teams of their era.

The Wreckers were also heavily scouted by baseball executive J.L. Wilkinson, along with the keen eye of Casey Stengel. Wilkinson recruited a number of the Wreckers to his new team in Kansas City – including Rogan, who was discharged in 1920 – and they, along with many members of Wilkinson’s All Nations barnstorming team, made up the inaugural roster of the Kansas City Monarchs.

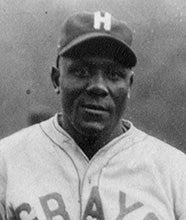

Jud Wilson, born in Remington, Va., was a tried and true D.C.-area man who joined the U.S. Army in June of 1918. He served in Company D of the 417th Service Battalion as a corporal and then returned to the nation’s capital, where he played on local semipro teams until signing with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1922. Wilson starred professionally on the diamond for decades, including with his hometown Homestead Grays and in Cuba. He is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, and is the only Hall of Famer to be buried on those sacred grounds.

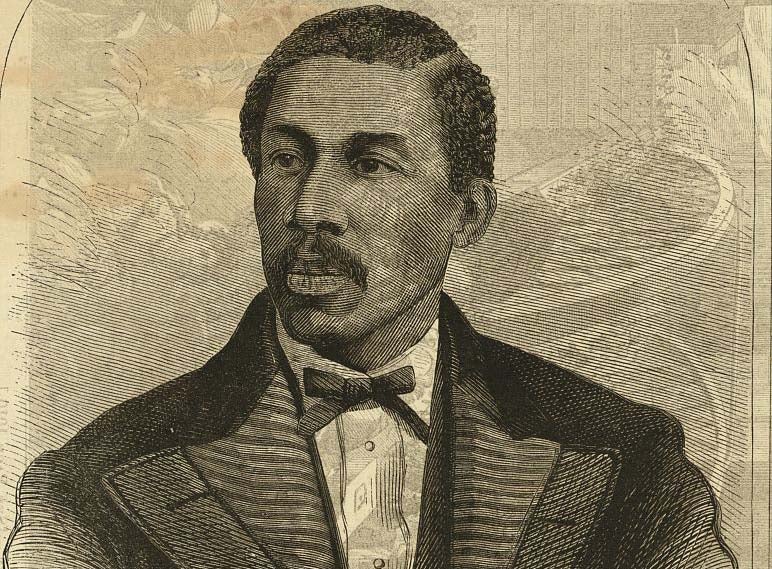

An early superstar, Louis Santop’s baseball career was perhaps the most influenced by his military service. Even his nickname, “Big Bertha,” in reference to his spectacular home run power, was derived from the World War I long-range artillery weapon.

When the slugger initially reported to Fort Dix in July of 1918, he’d been entrenched in baseball for nearly a decade, forming the legendary “kid battery” with Cannonball Redding and excelling on the diamond from New York to Cuba. Santop was initially discharged for being “physically unfit” with an arm that was “broken and badly twisted,” but when he reported again that winter in Norfolk, Va., he was deemed healthy enough to serve. He was a member of the U.S. Navy from 1918-1919 and was discharged at age 29.

The Hall of Fame and Museum honors Charleston, Rogan, Santop, Wilson and the 64 other baseball legends who served their country with bronze medallions in the Plaque Gallery, and celebrates visiting veterans by offering free year-round admission to active duty and retired career military members.

Isabelle Minasian was the digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum