Baseball History, American History and You

OUR NATIONAL PASTIME

We play it as kids, we watch it and listen to it as adults, and we pass down our love of the Game through generations. Baseball is an American family tradition.

It is in Cooperstown where we learn so much about the bond that baseball has with American culture.

Looking back, time and time again, baseball has been there, through the good times and the bad, often bringing us together. Those moments transcend the action on the diamond.

From the Civil War to Civil Rights and all points in between and beyond, the game of baseball reflects American life, from culture to economics and technological advances. It inspires movements, instills pride and even heals cities.

These stories are preserved and shared at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

These are just a few of the times where the history of our National Pastime and American history have crossed...

THE CIVIL WAR

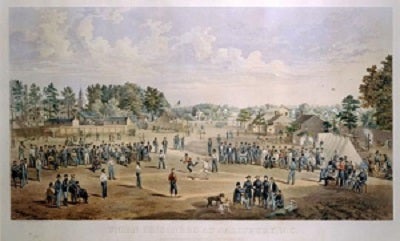

The first professional baseball games were played in the wake of a young nation's darkest days. The amateur version, however, has roots that reach back decades before the war began.

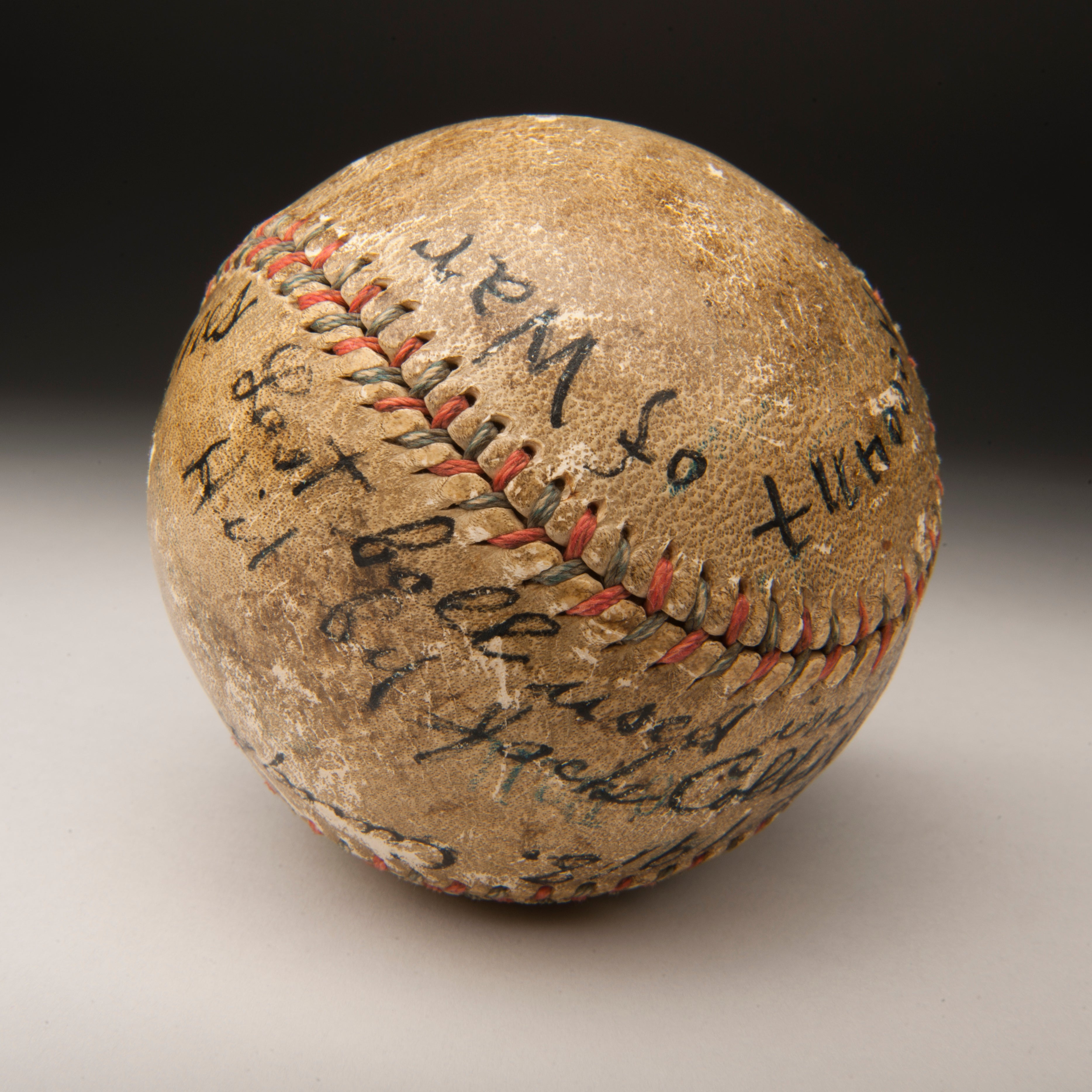

Reporters described baseball as a mania back in the 1840s; the sport was already established as a popular pastime when Civil War soldiers on both sides played it as a diversion. Many veterans took the game home after the war and it became a great unifier in the years that followed the bloodiest conflict in U.S. history.

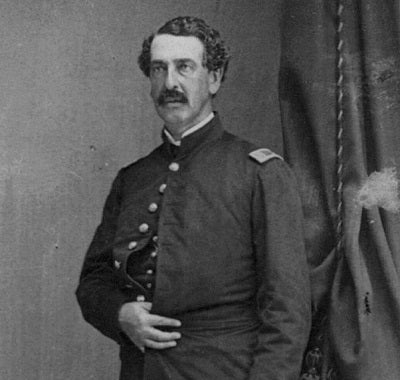

Though since disproved, the invention of the sport was originally believed to have occurred in Cooperstown, N.Y. and was credited to Civil War hero Abner Doubleday. Doubleday was at Fort Sumter in South Carolina when the first shots were fired in defense of the Union. He went on to rise to the rank of Major General and served with distinction during the Battle of Gettysburg.

WORLD WAR I

During World War I, 227 major leaguers served in various branches of the military. Among them were several future Hall of Famers, including Christy Mathewson, Branch Rickey, George Sisler and Ty Cobb, who all served in the Chemical Warfare Service, commonly referred to as “The Gas and Flame Division.” These baseball icons were instructors, training U.S. troops and conducting drills.

One of these drills sent soldiers into an airtight chamber into which actual poison gas was released. During one of these training exercises an accident occurred, causing Cobb and Mathewson to be exposed to the gas. Cobb recovered, but Mathewson was exposed to a much larger dose of poison, which damaged his lungs and contributed to his death from tuberculosis eight years later at the age of 45.

With our Country fighting WW I, Game 1 of the 1918 World Series between the Cubs and the Red Sox, which featured Babe Ruth on the mound for the Sox, was highlighted by a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” that stole the show.

The song would not become our official National Anthem until 1931, but when Red Sox third baseman Fred Thomas, an active-duty sailor on leave from Naval Station Great Lakes, heard the band strike up the song during the seventh inning stretch, he turned to face the flag, snapped to attention and offered a military salute. The other players seeing Thomas, turned to face the flag and put their hands over their hearts.

The fans, seeing what was happening on the field, roared to life, cheering and singing along, in a spontaneous show of patriotism. The “Star-Spangled Banner” has been performed at every World Series game since, and the tradition of playing the song before every big league game started 24 years later during World War II.

WORLD WAR II

In World War II, more than 500 major leaguers – and 37 Hall of Famers – served in the armed forces, with many of them sacrificing prime years of their careers.

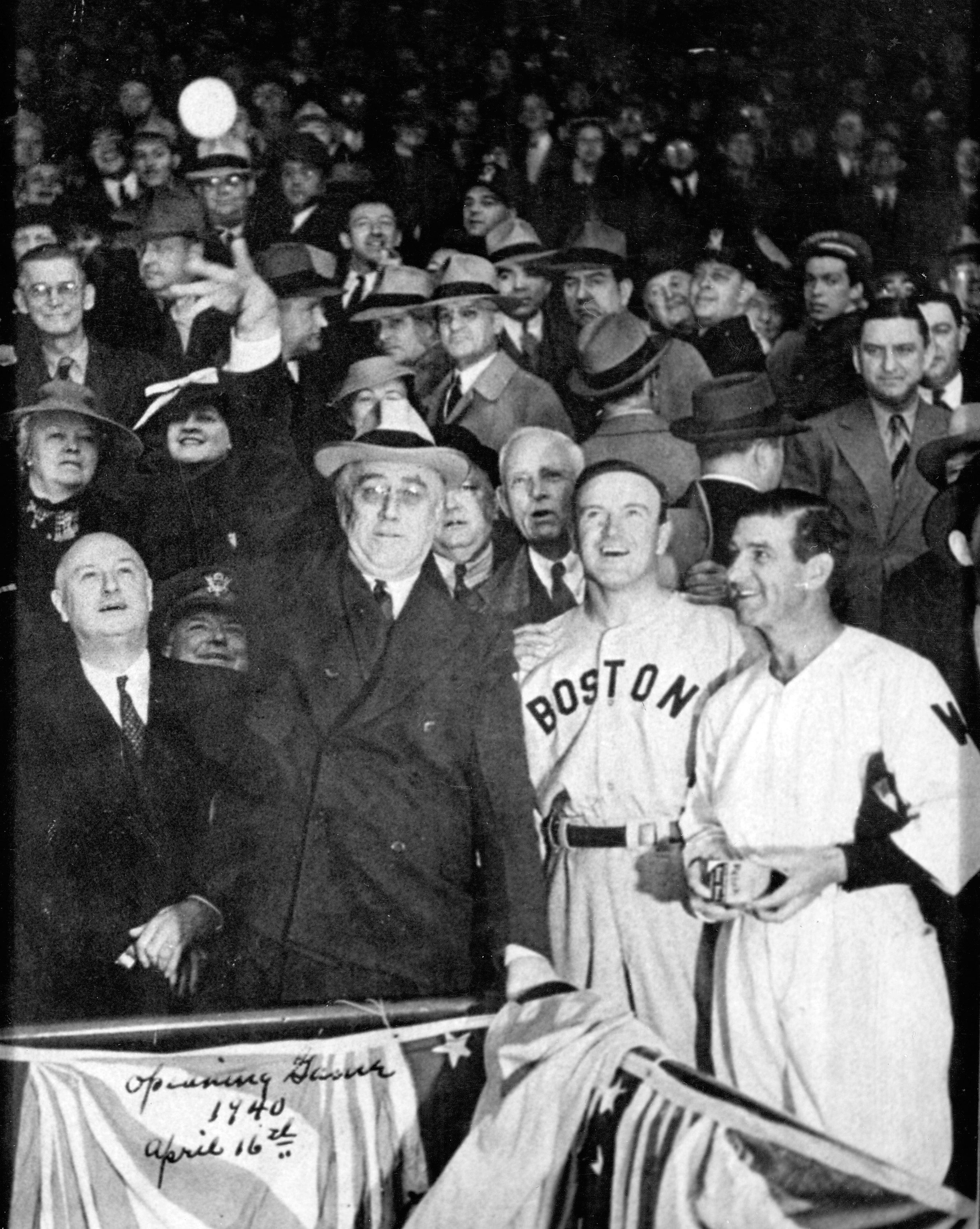

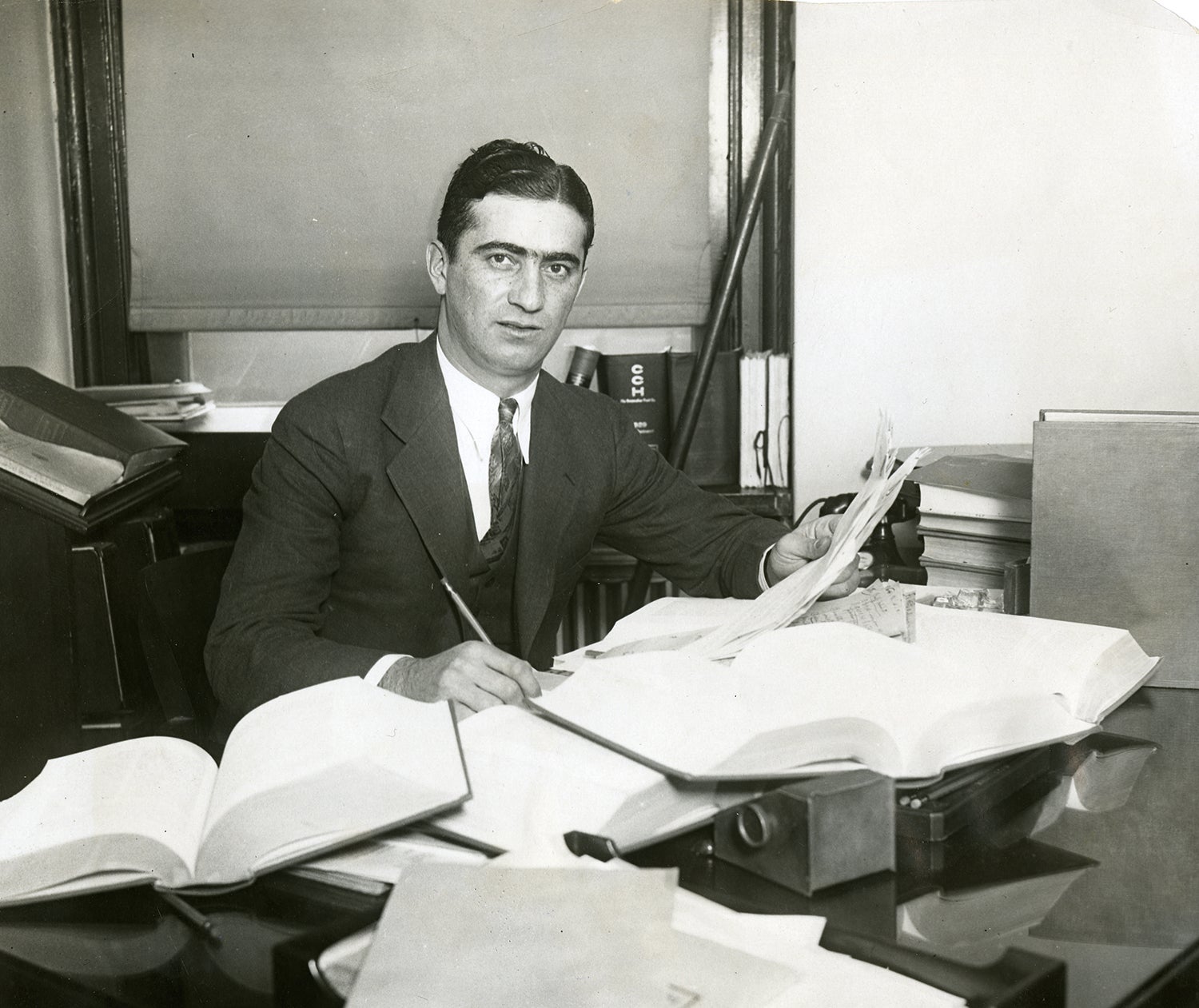

In January 1942, with the United States fighting in World War II, the Commissioner of Baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, wrote to President Roosevelt asking if professional baseball should continue or be suspended during the War.

In response, Roosevelt sent the “Green Light Letter” clearing the way for baseball to continue throughout the war. The President’s response to Landis read in part:

“I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going. There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before. And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.”

This historic letter from FDR to Landis is part of the collection in Cooperstown.

The War years also saw the founding of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, established in part to compensate for the loss of many of the best major league players to the war effort.

CIVIL RIGHTS

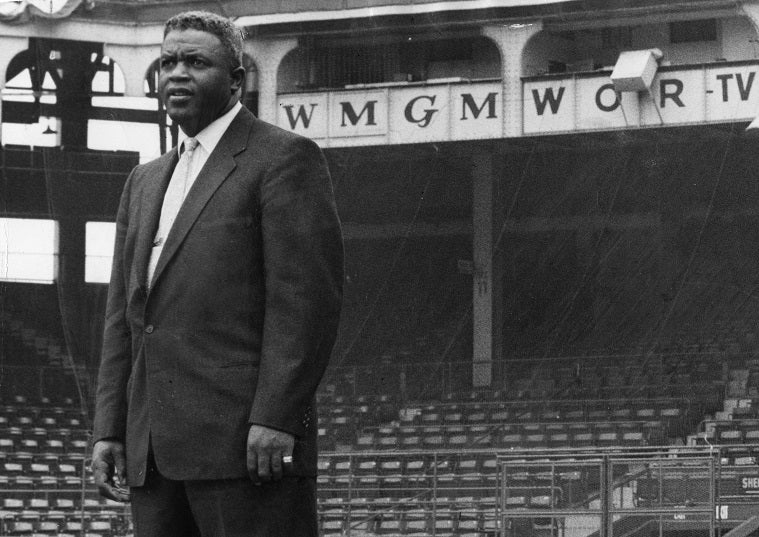

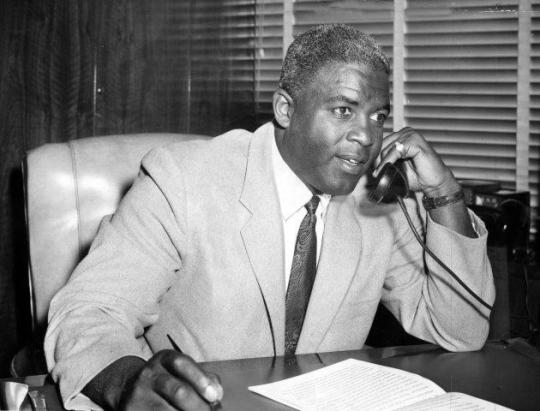

African-Americans played baseball on Southern plantations during the 1850s. A century later, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier and reintegrated the game. There were numerous strides and setbacks in between. An unwritten agreement barred Black players from professional leagues from the late 1800s and into the 20th century. Before that, the professional game had bucked the trend, as Bud Fowler – a native Central New Yorker – played in the 1870s and '80s despite the proliferation of Jim Crow laws.

Within the African-American community, baseball was a great source of pride as dozens of barnstorming teams traveled from town to town to entertain crowds. The Negro Leagues fielded outstanding players, many of whom have been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Baseball led the way on integration, as Jackie Robinson became a key symbol of equality during the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s.

“Jackie Robinson made my success possible,” said Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “Without him, I would never have been able to do what I did.”

The magnitude of those words cannot be overstated. Dr. King’s lasting work as a Civil Rights pioneer touched all areas of the American experience, yet he credited a baseball player with making his dream viable.

King's words speak to the breadth and depth of baseball’s presence in America. The game represents the American ideal at its root: That hard work and fair play are the keys to success.

Once Robinson was allowed to demonstrate his ability in the big leagues, the doors appeared open to everyone. It was a message that only baseball – with its power to cut across cultures – could deliver.

On Sept. 1, 1971, the Pirates became the first AL or NL team to field an all-black, or all-minority lineup. Roberto Clemente was part of the lineup that day, a fitting inclusion for a player who willingly spoke up about issues affecting Latino players of his era.

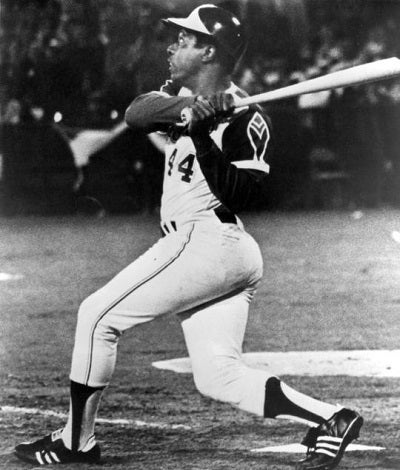

On April 8, 1974, Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run in front of a crowd of more than 53,000 at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, passing Babe Ruth’s record of 714. The Dodgers’ legendary broadcaster Vin Scully summed up the moment with his call:

"It’s a high drive into deep left center field. (Bill) Buckner goes back to the fence… It is gone. What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

Aaron’s uniform from this historic moment is on display in the Hank Aaron: Chasing the Dream exhibit on the Museum’s third floor.

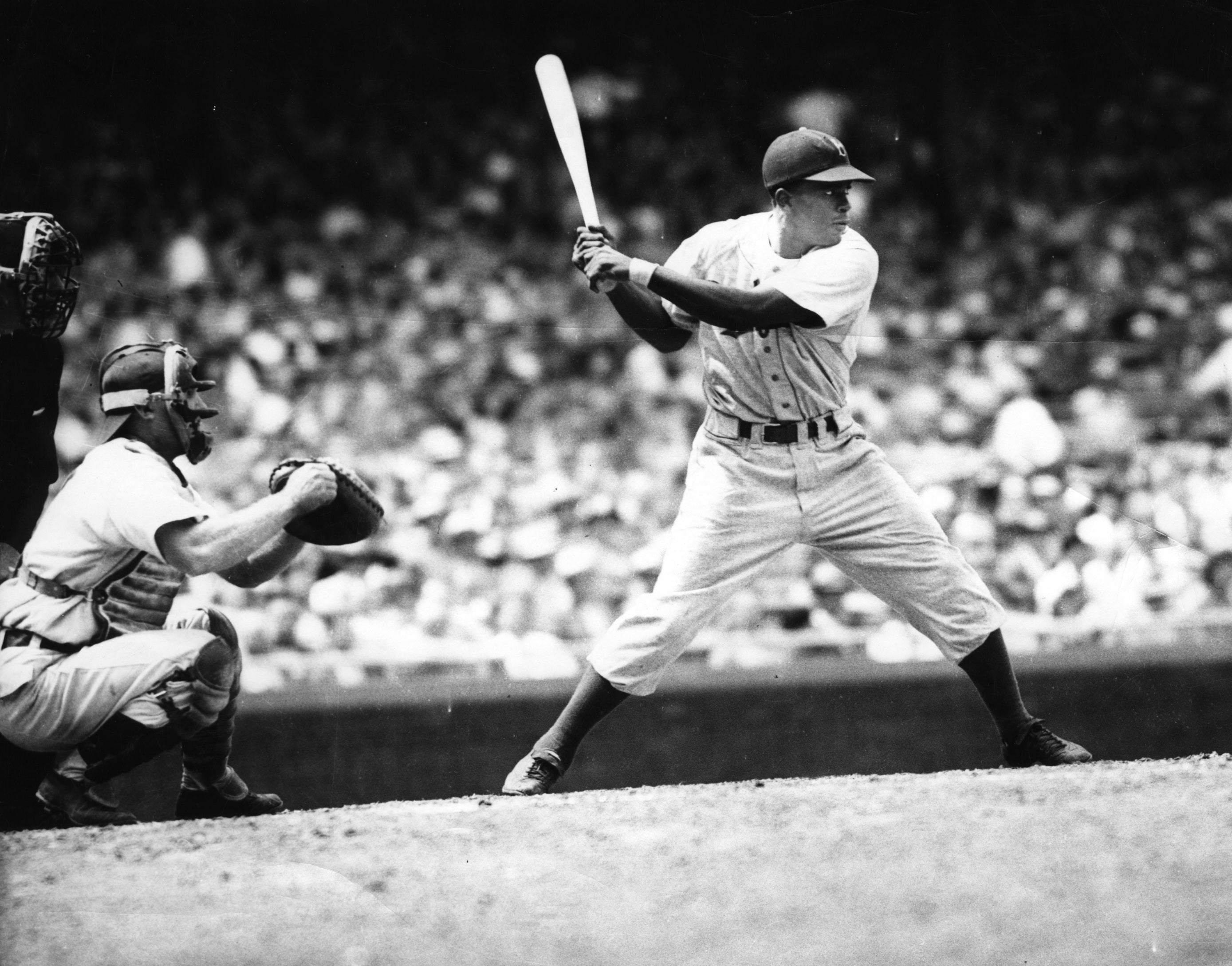

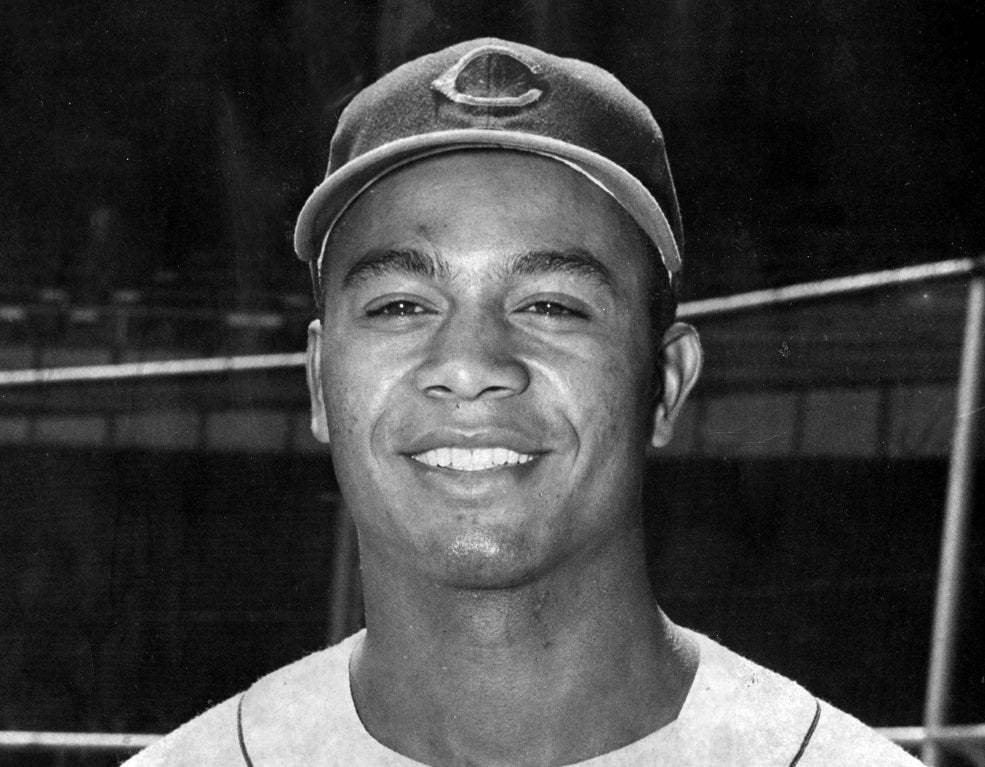

Exactly one year later, on April 8, 1975, Frank Robinson broke new ground in baseball's quest to truly become the National Pastime. Robinson, hitting second for the Cleveland Indians as their new player-manager, he was the first Black man to be a full-time manager in the AL/NL.

THE LAST 50 YEARS

Every baseball fan who is old enough to remember our Nation’s Bicentennial Celebration recalls April 25, 1976.

On that day, Rick Monday of the Chicago Cubs saved the American flag from being burned by protestors on the field during the fourth inning of a game at Dodger Stadium. When Monday came up to bat in the fifth inning, the Los Angeles Dodgers fans gave him a standing ovation and the scoreboard displayed the message, “RICK MONDAY…YOU MADE A GREAT PLAY.”

On the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier and paving the way for Black ballplayers to compete in the National and American Leagues, his No. 42 was retired across the sport. Commissioner Bud Selig, was joined on the field at Shea Stadium by Rachel Robinson and President Bill Clinton, to make the announcement.

BBWAA Career Excellence Award winner Claire Smith, who was covering the ceremony, said:

“When he (Selig) announced it, there was a collective gasp in the stadium, and around baseball. I was stunned. Obviously, it had never been done before in Major League Baseball to universally retire one number. And in the four major sports, it had not been done. ... Jackie Robinson is my hero. He's why I write. And that was the most moving thing I'd ever seen on a baseball field.”

The Character and Courage display features statues of Lou Gehrig, Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente that welcome every visitor to the Museum.

For many of us, 9/11 is a moment etched into our memories. The events of that day left us with a tremendous sense of loss and anger for what had been taken from us, and a heavy feeling that our lives would be changed forever. Thankfully, baseball was there to help us heal again.

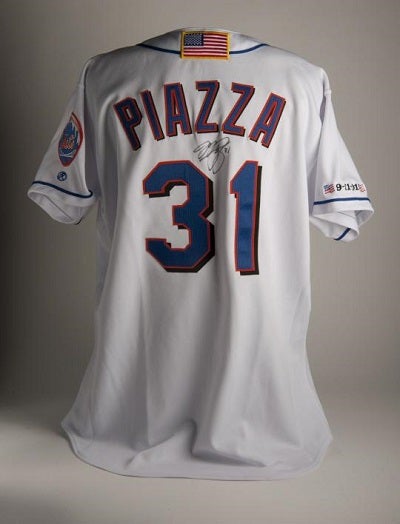

Just 10 days after the attack, on Sept. 21, Major League Baseball resumed in New York. The city was still reeling and coming to grips with a changed world. That game represented hope – and gave people faith that despite our terrible loss, America was going to persevere. The evening reached a crescendo as future Hall of Famer Mike Piazza of the New York Mets hit one out of Shea Stadium to beat the rival Atlanta Braves. The crowd went wild – screaming, jumping, hugging and crying together.

The jersey Piazza wore that day now splits time on display between the Museum in Cooperstown and the Mets Hall of Fame and Museum at Citi Field.

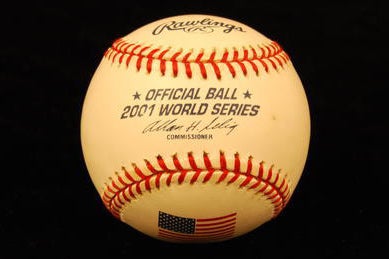

Just a few weeks later, in late October and early November 2001, the New York Yankees were facing the Arizona Diamondbacks in the World Series. Games 1 and 2 took place in Phoenix. When the series returned to New York for Game 3, President George W. Bush was at Yankee Stadium to throw out the first pitch.

In a show of American strength and perseverance, Bush strode to the mound wearing an FDNY jacket to honor the first responders, and as Yankee fans erupted in cheers of “USA, USA, USA,” the President delivered a first-pitch strike.

Years later, President Bush spoke about that moment, saying:

"I had never had such an adrenaline rush as when I finally made it to the mound, I was saying to the crowd, 'I'm with you, the country's with you' ... And I wound up and fired the pitch. I've been to conventions and rallies and speeches: I've never felt anything so powerful and emotions so strong, and the collective will of the crowd so evident."

The video clip of this moment is featured in the Whole New Ball Game exhibit on the Museum’s second floor.

The 2013 Red Sox proved "Boston Strong" with a World Series win in the shadow of the Boston Marathon bombings.

Again in Houston, baseball served an important purpose. As the region crawled back from the destruction of Hurricane Harvey, the 2017 Houston Astros claimed their first-ever World Series championship.

The Museum documents these moments and more. Moments in which baseball and our culture have intersected in powerful ways.