- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: The forgotten hero

#GoingDeep: The forgotten hero

On Oct. 1, 1874, a Dr. J. W. H. Hacks published an open letter in the Philadelphia City Item.

Now, friends of the lamented Catto, please help me in an honest and just cause, that is, to raise Money enough to erect a creditable Tomb Stone at, or as near the place where the body rested, as possible; I think we can find the spot. To further this object, I propose we reorganized the Famous, Reliable, and well-known PYTHIAN BASE BALL CLUB, and hire Ten of the best Base Ball players that can be obtained; pay them as much wages as possible; the same to be under regular base-ball restrictions and forfeitures, and for non-compliance to the rules and law; said players to be ready to enter the field on or about the 1st of April 1875, and continue in our service until the middle of October following.

Coming across the name “Catto” would have certainly struck a nerve for readers of the Philadelphia newspaper on that early autumn morning. Almost to the very day three years ago, he had been murdered in broad daylight a block away from his home on 814 South Street, caught in the jaws of a brutal race riot during the most important election in the city’s history.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

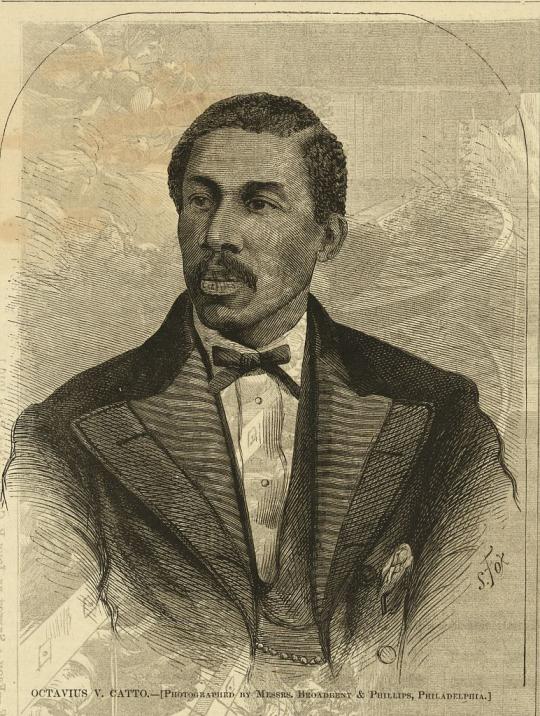

A Civil War veteran and a leading figure in Philadelphia as a voice for civil rights, Octavius Catto’s funeral was the largest the city had seen since Lincoln’s funeral train made its slow passage across Broad Street. Suffice it to say that Catto’s final resting place didn’t match that grandeur of the public spectacle and Dr. Hacks wanted to remedy that. It speaks volumes that he thought his best shot at accomplishing this goal –finding a way to ensure that Octavius Catto was remembered – was through baseball.

How fitting that Dr. Hacks would send out a baseball challenge in October to get a team together to play starting the following April. October has always been baseball’s true field of dreams: As one season ends, there is always next season; a diamond in the distance that sparkles and sings to the dreamer just as the cold winds start to blow and the bats are put away until signs of spring return.

But Dr. Hacks’ dream would go unfulfilled.

The grave of Octavius Catto would remain a plot of grass dozing alongside countless other unremarkable plots of grass in Lebanon Cemetery. And Philadelphia’s most prominent black baseball team, “the Famous, Reliable, and well-known PYTHIAN BASE BALL CLUB”, would remain in their current state, something between dormant and disbanded, as they had for the past three years – which is to say, ever since they lost their heart, soul, co-founder, captain, team manager and star: Octavius Catto.

That Dr. Hacks made no bones about finding the best ballplayers and paying them “as much wages as possible” showed how much the times had quickly changed. Not very long ago, the same City Item newspaper that welcomed Dr. Hacks search for paid ballplayers had published the following:

What must be the contempt for those who would degrade our great national game and make it a business? When such becomes the case, farewell to baseball. The excitement which is at present attended on these contests will cease.

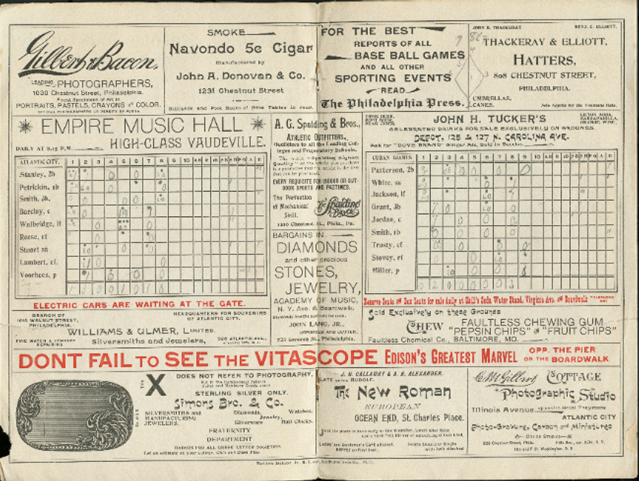

Just a few years before, the idea of paying baseball players had been looked upon with suspicion. In 1869, the all-white Cincinnati Red Stockings openly paid the 10 players on their roster, some seven times more than the average worker, and went on to log a 57-0 record. But by the end of 1870, the club’s costs had proved unsustainable, and the Red Stockings were no more. Dr. Hacks, however, was undeterred. This wasn’t a matter of looking to assemble a group of old friends or work colleagues for a sociable couple of hours of outdoor recreation. Dr. Hacks wanted the Pythians to return as a force capable of taking on all comers. The fourth season of baseball’s first professional league – the National Association – was rounding the corner toward its end, as baseball continued to hold the City of Brotherly Love in its thrall. So much so, in fact, that the National Association boasted not one, but two Philadelphia-based teams: The prominent Athletics and the less-regarded Whites. The two teams were on their way to third and fourth-place finishes, respectively, as the Boston Red Stockings – a team stacked with five future Hall of Famers – pulled away from the competition.

With the exploits of these big league teams appearing regularly in the local papers’ game reports and box scores, Dr. Hacks must have thought about what once might have been. The Pythians had received some press as well once upon a time. The New York Clipper, having witnessed a game between them and another team of Black ballplayers visiting from Washington, D.C. flashed across one of their pages the headline:

COLORED BALL PLAYERS

Dr. Hacks remembered them as more than that: Cannon on the mound and leading off; Catto at second; Graham in left; Hauley behind the plate; Cavens at first; Burr in right; Adkins at third; Morris in center; and Sparrow at short and batting ninth. They racked up nine wins against only one loss. But that late July day in 1867 already seemed so long ago. As did the promise of those days, when other Black social clubs would come to town with their baseball nine and seed a rich social atmosphere of picnics, dances and banquets that would last for days. The promise of those days. The Pythians flourished as time passed and, feeling they had found the best calling card by which to publicly challenge the status quo, they sent a formal challenge to every white baseball team in the city.

And, eventually, one accepted the challenge.

On Sept. 3, 1869, the Olympics of Philadelphia – a team with roots dating back to the 1830s – became the first white baseball team on record to play a black baseball team. And their 44-23 victory over the Pythians did better for the Pythians than the final score would lead one to think. The press had descended onto Philadelphia for the game and left impressed with the skill and fight displayed by the city’s premier Black baseball team. So much so that the event even landed on the front page of The Baltimore Sun. “The novelty of the affair drew an immense crowd, it being the first game between a white and a colored club.”

The Pythians would beat the next white team they played. And Hacks, in looking to memorialize Catto, also found himself caught up in the rapture of those days: He contemplated getting the band back together.

The wounds of the Civil War were still fresh, but the lure of baseball did not discriminate. Instead, baseball had become the perfect vehicle for Catto’s views of racial equality and social change. And he was not alone. Even Frederick Douglass was known to take time out of his schedule to enjoy a ballgame. The Clipper reported of one such day in which “Mr. Frederick Douglass was present and viewed the game from the reporter’s stand.” Douglass’ son, Charles, played third base for the Pythians' rivals – the Alert – that day. And the Alert were yet another all-Black baseball team, one of many flourishing at the time – there were the Mutual Base Ball Club and the Excelsior Base Ball Club, also of Washington, D.C.; the Moravian Base Ball Club of Harrisburg, Pa.; the National Excelsior Club of Philadelphia; the Monitors and the Uniques of Brooklyn; the Oneida Base Ball Club of Bergen, N.J.; the Liberty Base Ball Club of Jersey City, N.J.; and scores more. America was barely out of the shadow of the Civil War and Black baseball was already burgeoning. That same October, the Uniques and the Mutuals squared off for a self-proclaimed “championship of colored clubs” and, heartened by the success of their season – in which they not only hosted traveling black teams from out of state but also played several well-attended games against white teams – the Pythians decided to apply for official recognition as a professional team.

They were turned away. Twice. First, in October 1867, by their local professional organization – the Pennsylvania State Base Ball Association – about which the Pythian club secretary (and Catto’s best friend) Jacob White, Jr. noted:

Whilst the Committee on Credentials were making up their report, the delegates clustered together in small groups to discuss what action should be taken. Sec. Domer stated although he, Mr. Hayhurst, and the President were in favor of our acceptance, still the majority of the delegates were opposed to it, and they would advise me to withdraw my application, as they thought it were better for us to withdraw than to have it on record that we were black balled.

And then again in December 1867, when the Pythians, undeterred by their prior setback, again applied for membership at the year-end conference of the National Association of Base Ball Players. By the time the Association had concluded its business at the conference, it had accepted “eight State Associations, representing 237 clubs…eight clubs [as] probationary members…eight clubs whose applications are more or less irregular” and to ban all Black ball players from the Association. And further, to make sure they had finessed away any confusion regarding the matter, any team caught with a Black player on its roster from that point on would face expulsion from the ranks of “organized” baseball.

But as you can never unring a bell, so, the Pythians persisted playing the game they loved despite being relegated to permanent amateur status. They traveled out of state for games against other Black clubs, much like the Mutuals and Actuals did when they visited Philadelphia for the 1867 championship. In 1868 and 1869, the Pythians consolidated their standing as an elite team, albeit an elite team blackballed from the professional ranks by its white peers. They arrived at their games wearing blue pants and a white bibbed shirt with a large gothic “P” emblazoned on the chest; and the club, by 1868, was so bursting at the brim with players that they had four distinct teams.

And yet, come 1870 the Pythians weren’t playing at all.

In February of that year, Congress passed the 15th Amendment, which was the third and final of the “Reconstruction Amendments” – this one granting Black men the right to vote for the first time since 1838. Catto, along with many of his other prominent teammates were swept up in this seismic event, although the initial tremors could never anticipate what was eventually to come.

Catto’s skill in coordinating, organizing and encouraging extended well beyond the bounds of a baseball field. He was a committed social activist: During the Civil War, he had fought for Blacks to have the right to serve in the military; he led organized protests of the Philadelphia trolley system that led directly to its desegregation; he served as secretary of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League; and he was a major and inspector general of the Fifth Brigade, First Division of the National Guard of Pennsylvania – a position which required he have a horse, a sword and a firearm. With the new political reality, Catto knew he would be needed in some, and perhaps all, of these capacities in the year ahead: There was an election upcoming in October and the following year would bring the event everyone in Philadelphia had their eye on – the mayoral election of 1871.

Under the circumstances, the more minor election of 1870 came and went with far less fireworks than one would have expected. A little rioting was reported to have taken place when whites, many from Catto’s integrated and heavily immigrant Fourth Ward, attempted to prevent Blacks from voting. None of these flailing efforts worked: Catto’s planning had helped ensure a high Black voter turnout in the Fourth Ward as well as throughout the city that day. Like the Pythians, Black voters had been tightly organized and well-drilled: They had gone to the polls early with ballots filled out beforehand and made sure to vote quickly. By nine o’clock in the morning, just about any Black resident of Philadelphia who had any intention of voting had already done so. The voting tactic had caught would-be instigators by surprise and played a major role in suppressing violence instead of suppressing votes. But, with the mayorship up for grabs the following year, the 1871 election would prove a sterner challenge.

Meanwhile, it took a year for the Pythians to regather without the guiding light of their second baseman. But after a year in the void, the team took to the field once more for the 1871 season…although only twice and without their beacon, Catto, who would take another year’s sabbatical from the game, devoting his time to traveling to Washington and social organizing in preparation for Philadelphia’s high-stakes general elections, which was set for the 10th of October of that year. Baseball was part of Catto’s vision of a more perfect union. But baseball, for him at least, would have to wait.

Still, as a sign of Black baseball increasingly simply becoming part of the news, the Philadelphia Inquirer went with the simple title of:

BASE BALL

when on, Sept. 20, 1871, the paper reported on a game between the Pythians and the Unique – a team from Chicago that had also taken to challenging black and white baseball clubs. Unbeknownst to either team at the time, tragedy awaited them. The Unique would return to Chicago and find themselves in the middle of the Great Fire of Chicago that would burn unchecked for three days. And when the fire was finally put out in Chicago, on Oct. 10, Philadelphia would barely survive a day that would go down as one of the worst in its long history.

The phenomenal Black voter turnout for the 1870 election only increased the opposition’s desperation to snuff it out, especially with the city’s very seat of power up for grabs. Violence erupted as never before through the Fourth Ward and across the city as rioting whites attempted to intimidate Black voters to keep them from the polls. One contemporary account noted that “the voters, contrary to all precedent, were ranged in two lines, one of blacks, the other whites, between whom there was a perpetual struggle to get in votes of the rival races, resulting almost invariably either in the colored man giving up the attempt or else a fight, in which after a drubbing by his white antagonist he would be arrested and locked up.” Two Black men were shot and others waiting in line to vote were attacked by mobs. Catto, always aware of this possibility, had dismissed his students from the Institute early that day.

His short walk home to South Street became a longer one amidst the chaos of that afternoon, as he followed a friend’s advice on a safer, more circuitous route back to his door. Nevertheless, a block from his home Catto ran into a white mob. An argument ensued, then seemed to peter out and Catto continued past them only for a volunteer fireman named Frank Kelly to pull out a pistol and shoot at Catto from behind. One bullet lodged into his right arm. One lodged into his left shoulder. Catto stumbled and tried to find cover behind the trolleys that he had worked so tirelessly to desegregate. Kelly chased after him and fired again. And again. One bullet found Catto’s left thigh. And a fourth lodged into the right ventricle of his heart.

While one police officer who had rushed to the scene held Catto in his arms as he died, another helped Kelly escape out a backdoor. Six years later, Kelly would be found – in the Unique’s hometown of Chicago – and he would stand trial in Philadelphia, where an all-white jury would find him innocent on all counts.

The Pythians would not rise from the dead at Dr. Hacks’ suggestion. Not even the offer of money could stir 10 ringers in need of cash to stand up, be counted and put the blue “P” on their chest. Eventually, in 1887, some form of the Pythians would emerge again and do what up until that point had never been done: They founded an all-Black baseball league. It wouldn’t last a season, as logistical challenges, financial challenges and Jim Crow led to the league folding after only a few games. The Pythians would never play the game of baseball again. And it would be another 120 years before Catto’s grave – after first being relocated to suburban Collingdale – would receive that upgrade Dr. Hacks wished for way back in 1874. In 2007, the Octavius Catto Foundation funded a large black headstone at Catto’s grave. At the top it reads:

THE FORGOTTEN HERO

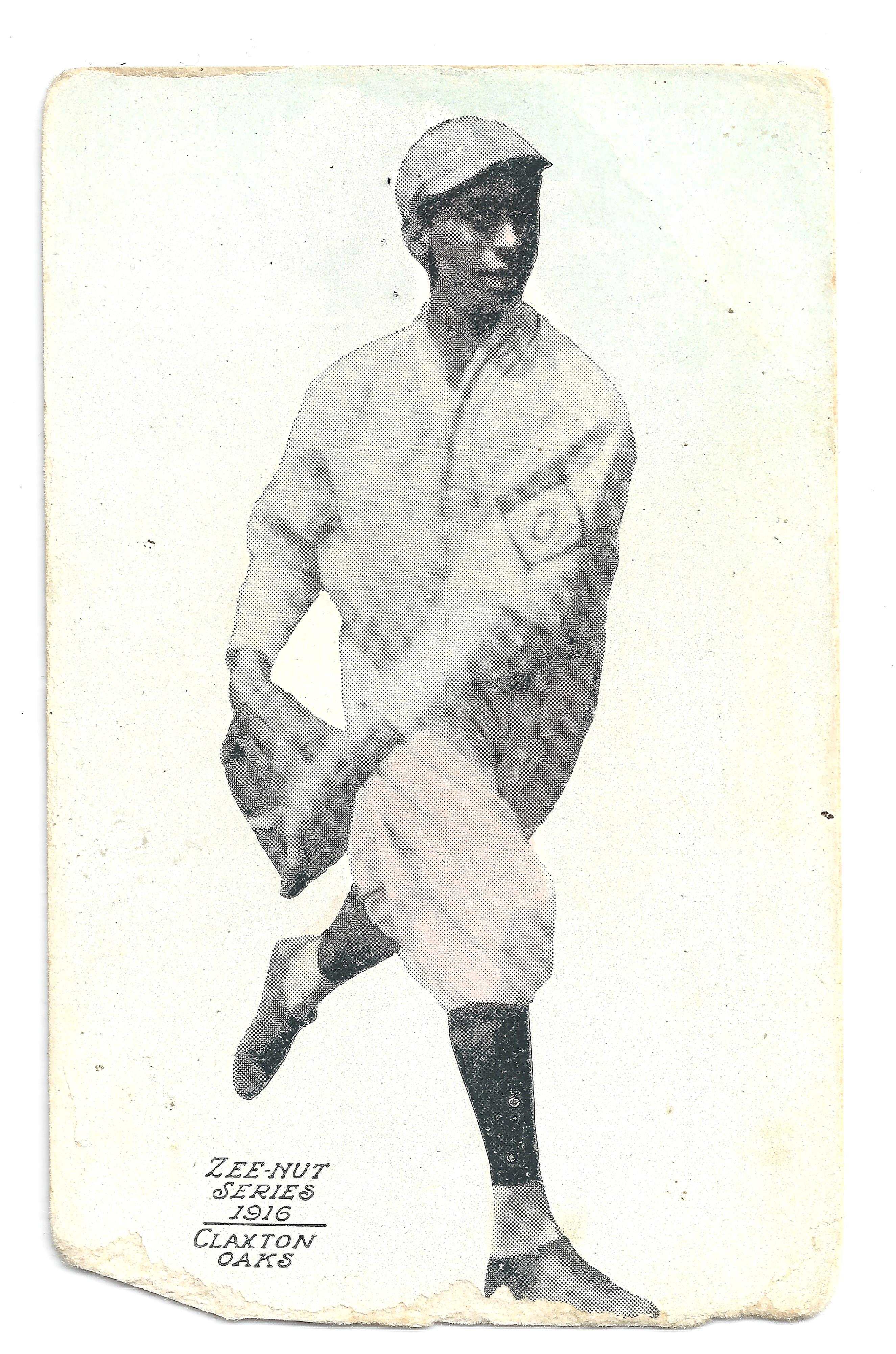

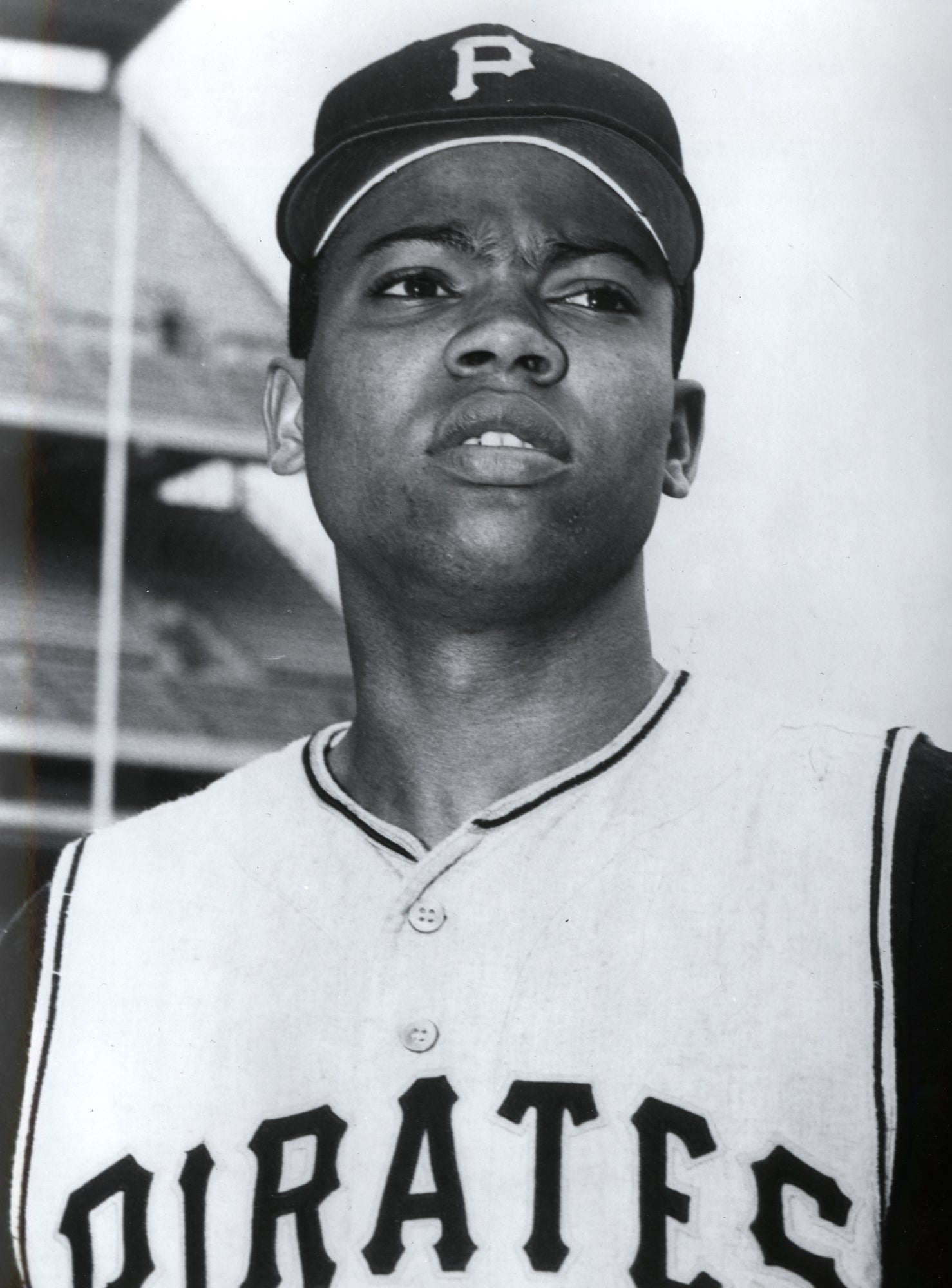

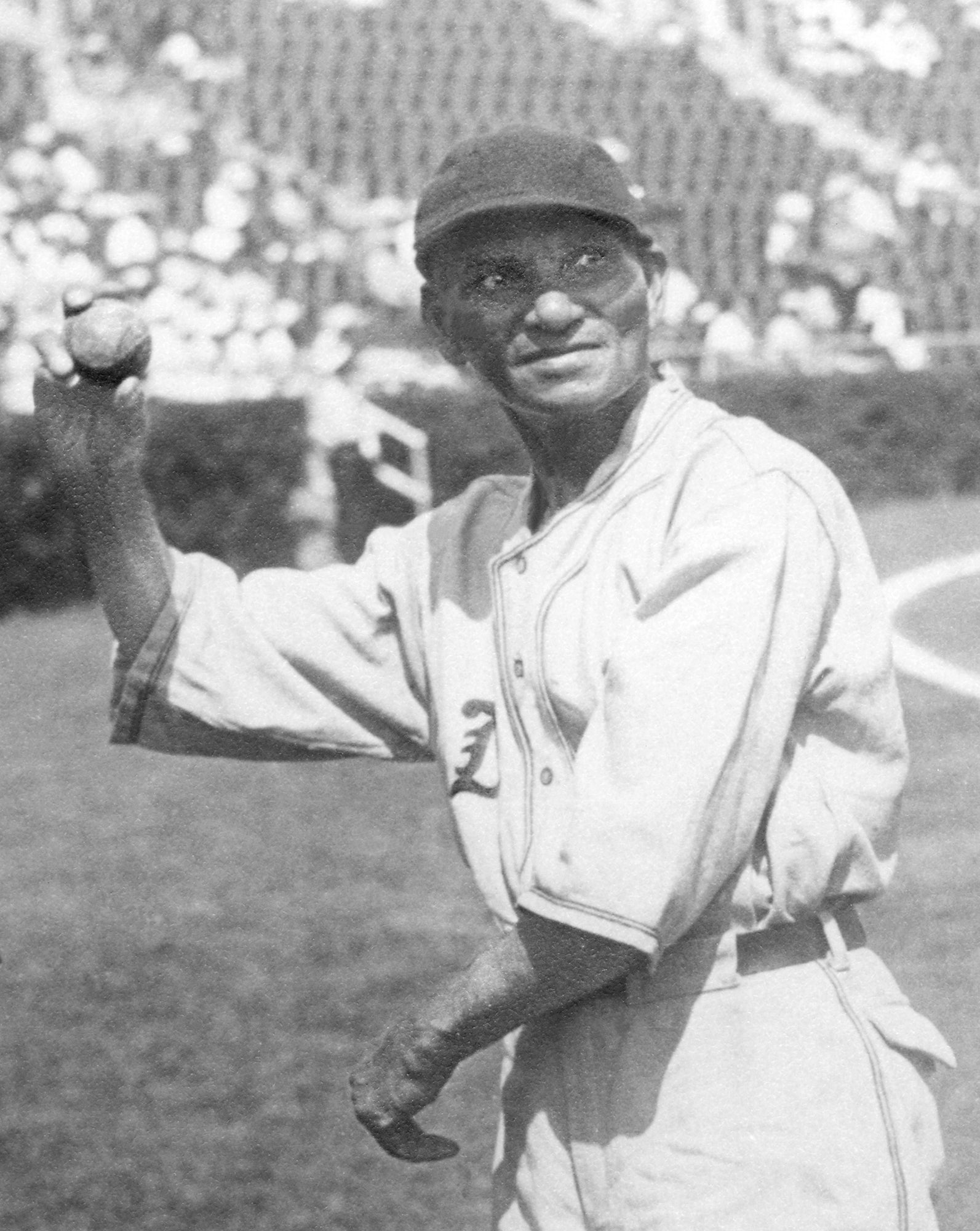

The Pythians were gone, never to return. But their efforts solidified Philadelphia as a haven for Black baseball. The Philadelphia Giants would rise in 1902 and be around until 1911. Then came the Hilldale Club, one of the most renowned Black baseball teams of the 1920s. Hilldale proved to have more staying power than its predecessors, flush with fresh talent from the Great Migration and the surging popularity of the game. They signed great players, including future Hall of Famers Judy Johnson, Oscar Charleston and Biz Mackey. Ten years into their existence they joined up with other Black baseball teams as Negro League baseball was thriving.

In the span of four September days in 2017, the city of Philadelphia erected a statue of Catto in his honor outside of City Hall – the city’s first memorial statue of a Black person in its 338-year history – and a commemorative plaque at the Jefferson Ball Parks in North Philadelphia in honor of the Pythians’ game against the Olympics that broke baseball’s first color barrier. The dots that connect Catto’s historical legacy to his baseball legacy span from one end of the city to the other, drawing a line across the heart of the city that can never be erased.

Rowan Ricardo Phillips is a Curatorial Consultant for the Hall of Fame’s ongoing Black Baseball Initiative.