- Home

- Our Stories

- One hundred years later, sale of Ruth to Yankees remains pivotal point in history

One hundred years later, sale of Ruth to Yankees remains pivotal point in history

For fans of the Boston Red Sox, the unthinkable, unimaginable, unfathomable happened 100 years ago with the sale of Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees.

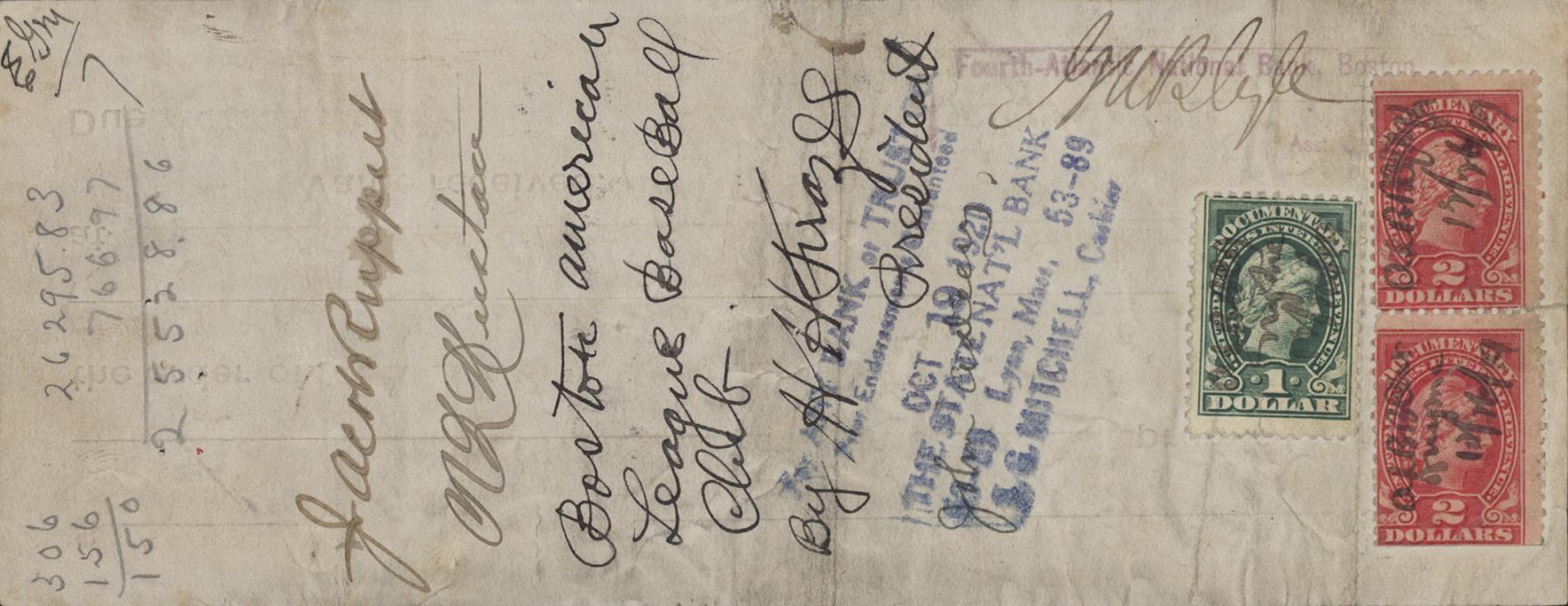

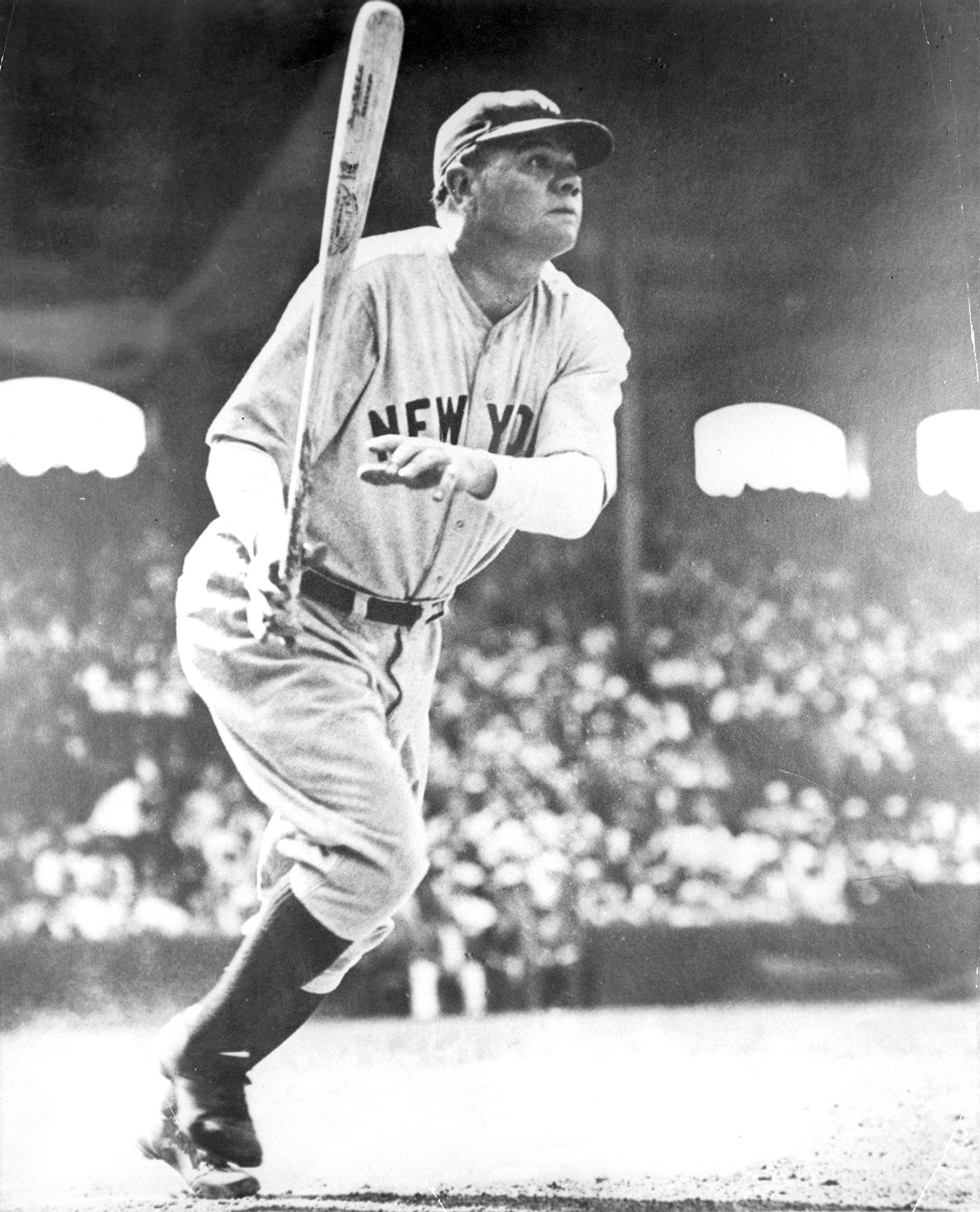

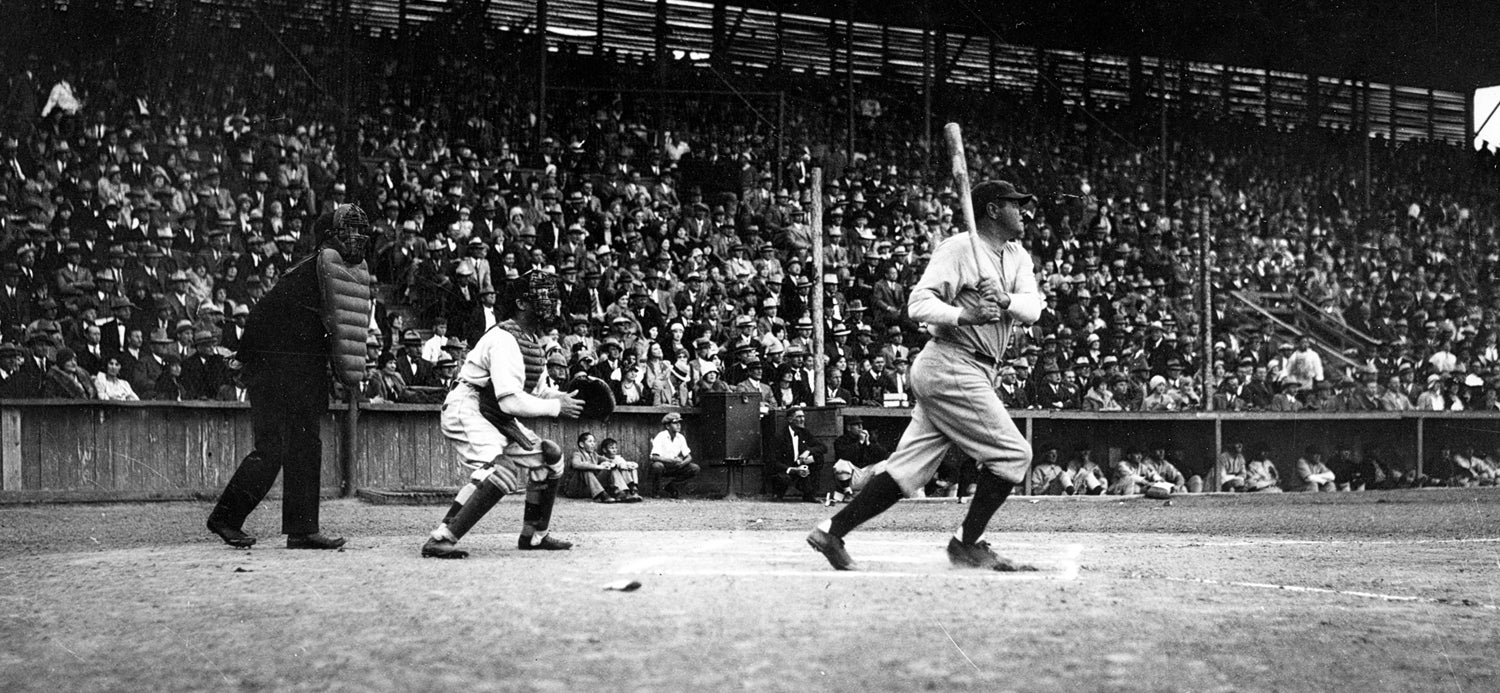

Ruth, all of 24 years old, had made the transition from star southpaw pitcher to the premier slugger in the game by 1919. Now patrolling left field for Boston, and thanks to his powerful left-handed stroke, he clubbed 29 home runs that set a new single-season big league record. But then the news broke. Ruth would soon be playing 77 game at the Polo Grounds – his home ballpark until Yankee Stadium opened in 1923 - with its short right field fence.

It was announced on Jan. 5, 1920 – though the transaction had been consummated a week earlier – that Ruth was now a member of a rival American League franchise.

Newspapers across the country shared the news with provocative headlines: “Red Sox Sell Ruth for $100,000 Cash” read the Boston Globe; “Ruth Bought by New York Americans for $125,000, Highest Price in Baseball Annals” blared The New York Times; “New York Yankees Buy Babe Ruth from Boston Red Sox” stated the Chicago Tribune.

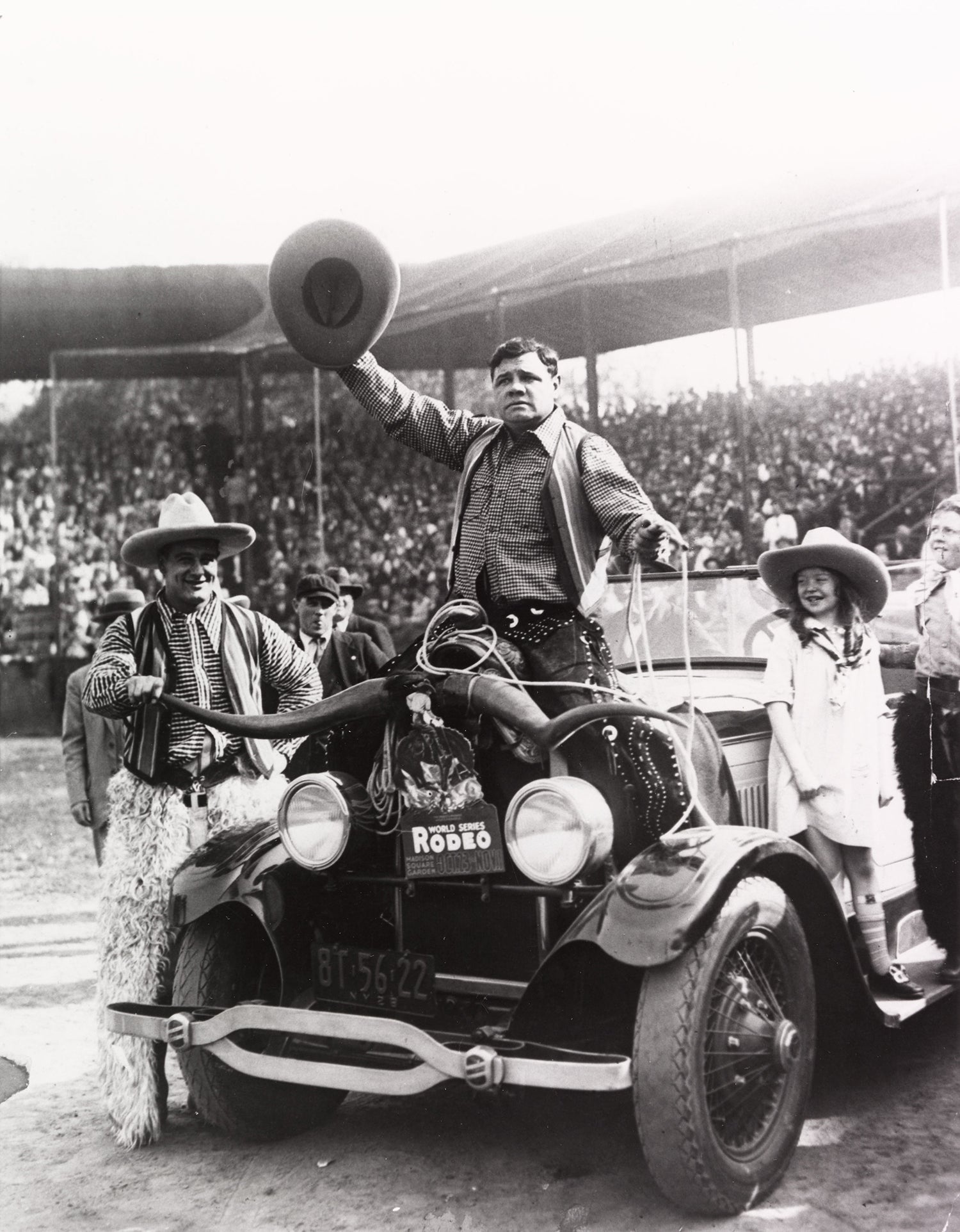

“Like all things Ruthian, everything about Babe Ruth’s sale from the Red Sox to the Yankees was outsized,” said Tom Shieber, the lead curator on the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s

“The price tag was unparalleled in sports history, the story was obsessively covered in the press, and every last detail was voraciously consumed by baseball fans nationwide. With the possible exception of the Louisiana Purchase, what other acquisition has reached the same level of long-term recognition in the American public’s conscience?”

So how did it come to this, that Ruth, a legend in his own time, was shipped out of Boston just as his offensive prowess was emerging? Coming off a 1919 season in which he led the Junior Circuit with not only his 29 homers but also 113 RBI and 103 runs scored, the Colossus of Clout wanted a new contract that would pay him $20,000 per season. Prior to the 1919 season, Ruth had signed a three-year deal with the Red Sox that would pay him $10,000 annually.

“You can say for me,” said Ruth to the Boston Globe in on Oct. 24, 1919, while awaiting train in Boston station heading to Los Angeles, “that I will not play with the Red Sox unless I get $20,000. You may think that sounds like a pipe dream, but it is the truth. I feel that I made a bad move last year when I signed a three-year contract to play for $30,000. The Boston club realized much on my value and I think that I am entitled to twice as much as my contract calls for.”

By December 1919, the war of words had escalated, and Red Sox president and owner Harry Frazee hinted he might sell Ruth, stating: “I’m willing to trade any man on my team, excepting only Harry Hooper.” Those Boston baseball fans whose ears were close to the ground were thus prepared to eventually hear Ruth had been sold to another club.

“The price was something enormous, but I do not care to name the figures. It was an amount the club could not afford to refuse,” said Frazee when making the announcement of Ruth’s sale to the press at Red Sox headquarters. “I should have preferred to have taken players in exchange for Ruth, but no club could have given me the equivalent in men without wrecking itself, and so the deal had to be made on a cash basis. No other club could afford to give the amount the Yankees have paid for him, and I do not mind saying I think they are taking a gamble. With the money, the Boston club can now go into the market and buy other players and have a stronger and better team in all respects than we would have had if Ruth had remained with us.

“I do not wish to detract one iota from Ruth’s ability as a ballplayer nor from his value as an attraction, but there is no getting away from the fact that despite his 29 home runs, the Red Sox finished sixth in the race last season,” Frazee added. “What the Boston fans want, I take it, and what I want because they want it, is a winning team, rather than a one-man team which finishes in sixth place.”

The 1919 Red Sox, with Ruth leading the way, finished the campaign with a 66-71 record, good for sixth place in an eight-team AL. The Yankees, without Ruth, finished in third with an 80-59 mark. By 1920, the Yankees were on their way to long-term success at 95-59, while Boston, at 72-81, continued a lengthy championship drought that would finally end with a World Series title in 2004.

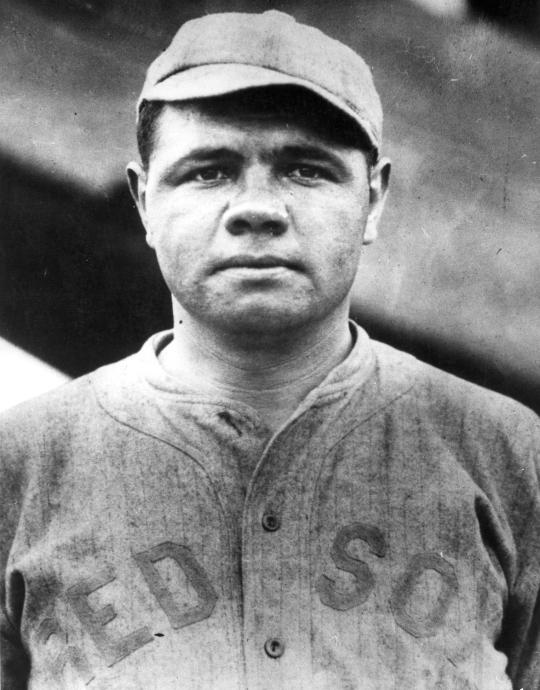

“I am not at liberty to tell the price we paid,” smiled Yankees co-owner Jacob Ruppert after he had made the announcement of the Ruth acquisition. “I can say positively, however, that it is by far the biggest price ever paid for a ballplayer. Ruth was considered a champion of all champions, and, as such, deserving of an opportunity to shine before the sport lovers of the greatest metropolis of the world.”

Then, in a bit of foreshadowing, Ruppert added, “It is not only our intention, but a strong life purpose, moreover, to give the loyal American League fans of greater New York an opportunity to root for our team in a world’s series. We are going to give them a pennant winner, no matter what the cost. I think the addition of Ruth to our forces should held greatly along those general lines. Yet the fans can rest assured we by no means intend to stop there. Eventually we are going to have the best team that has ever been seen anywhere.”

Ruth, contacted in Los Angeles where Yankees manager Miller Huggins helped secure a contract that would pay the home run king $20,000 per season in 1920 and ’21, claimed to be not surprised by sale to New York, adding: “When I made my demand on the Red Sox for $20,000 a year I had an idea they would choose to sell me rather than pay the increase and I knew the Yankees were the most probable purchasers in that event.”

Yankees pitcher Bob Shawkey, who was at the team’s offices when Ruppert announced the sale, said jubilantly: “Gee, I’m glad that guy’s not going to hit against me anymore. You take your life in your hands every time you step up against him. You just throw up anything that happens to come into your head, with a prayer, and duck for your life with the pitch.”

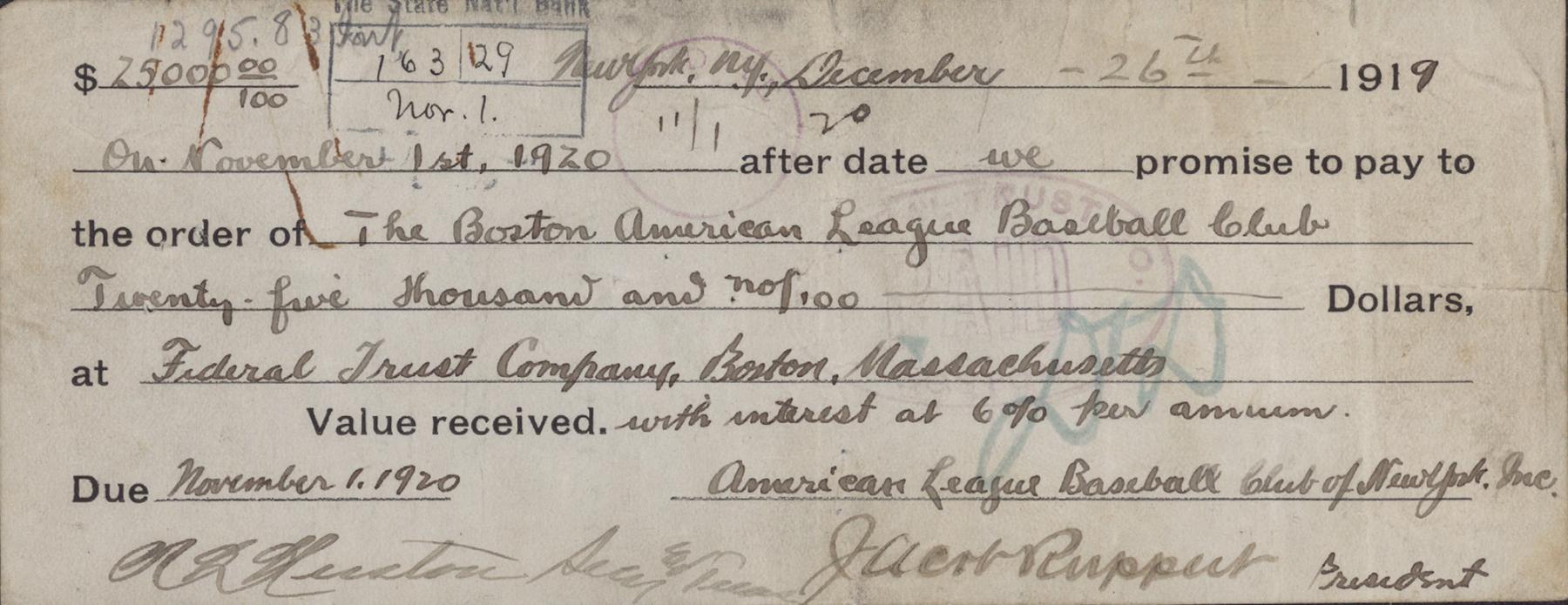

While the official sale price of Ruth was not made public at the time of the transaction, numbers were speculated about. According to research compiled by Michael Haupert, Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, the actual purchase price was $100,000, payable in four annual installments of $25,000 at six percent interest, with New York making the first payment on Dec. 19, 1919.

“When news of the sale first broke, there were reports that the deal was more complicated than the simple cash transaction announced by Colonel Ruppert,” wrote Haupert in the book The Babe. “Rumors began to crop up about a second part to the deal: a loan from the Yankees to Frazee in an amount ranging between $300,000 and $400,000. In this case, the rumors proved to be true. On May 25, 1920, Ruppert made a personal loan to Frazee for $300,000, with Fenway Park as collateral. Because Frazee owned the Red Sox and Ruppert owned half of the Yankees, and the collateral for the loan was Fenway Park, it was very much a part of the Ruth transaction.”

Part of the permanent collection at the Hall of Fame is a Ruth promissory note, dated Dec. 26, 1919, and donated in 1999. The note, signed by Ruppert and Frazee, is for the sum of $25,000.

“The 1919 promissory note for the sale of Babe Ruth from Boston to New York is a critical piece of baseball history,” said Hall of Fame Librarian James Gates. “The results of this transaction had immediate impact on the caliber of both teams for many years to come, and long-term implications on the growth popularity of baseball as America’s National Pastime.

“This event is a pivotal moment in baseball history and in American history. We are pleased to have this document as part of our archival collection. Given that we did not acquire this item until 80 years after the original event, it also shows the importance of patience and persistence in our efforts to further develop our collections.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum