- Home

- Our Stories

- No-pitch intentional walks no new idea

No-pitch intentional walks no new idea

“An intentional walk always comes at a crucial time, and the pitcher should be made to throw the ball. Anything can happen, and sometimes does.”

Sound familiar?

That quote comes from Red Sox manager Pinky Higgins back in 1956 when the American League experimented during Spring Training with directly ushering a batter to first base without tossing a single pitch via an intentional walk.

This particular baseball debate cropped up again recently regarding improving the game’s pace of play when, on Feb. 22, it was announced that the Major League Baseball Players Association agreed to Commissioner Rob Manfred’s request to eliminate the four-pitch intentional walk in favor of a manager’s signal from the opposing dugout, one of a number of rules modifications for the 2017 season.

"The intentional walk with no pitches was a small change in a much larger package," Manfred said. "We don't think that particular change — we know how the math works — is going to have a momentous impact on the game. By the same token, every little change that makes the game faster I personally believe is a good thing for the game over the long haul."

The wording of the new rule: “The start of a no-pitch intentional walk, allowing the defensive team's manager to signal a decision to the home plate umpire to intentionally walk the batter. Following the signal of the manager's intention, the umpire will immediately award first base to the batter.”

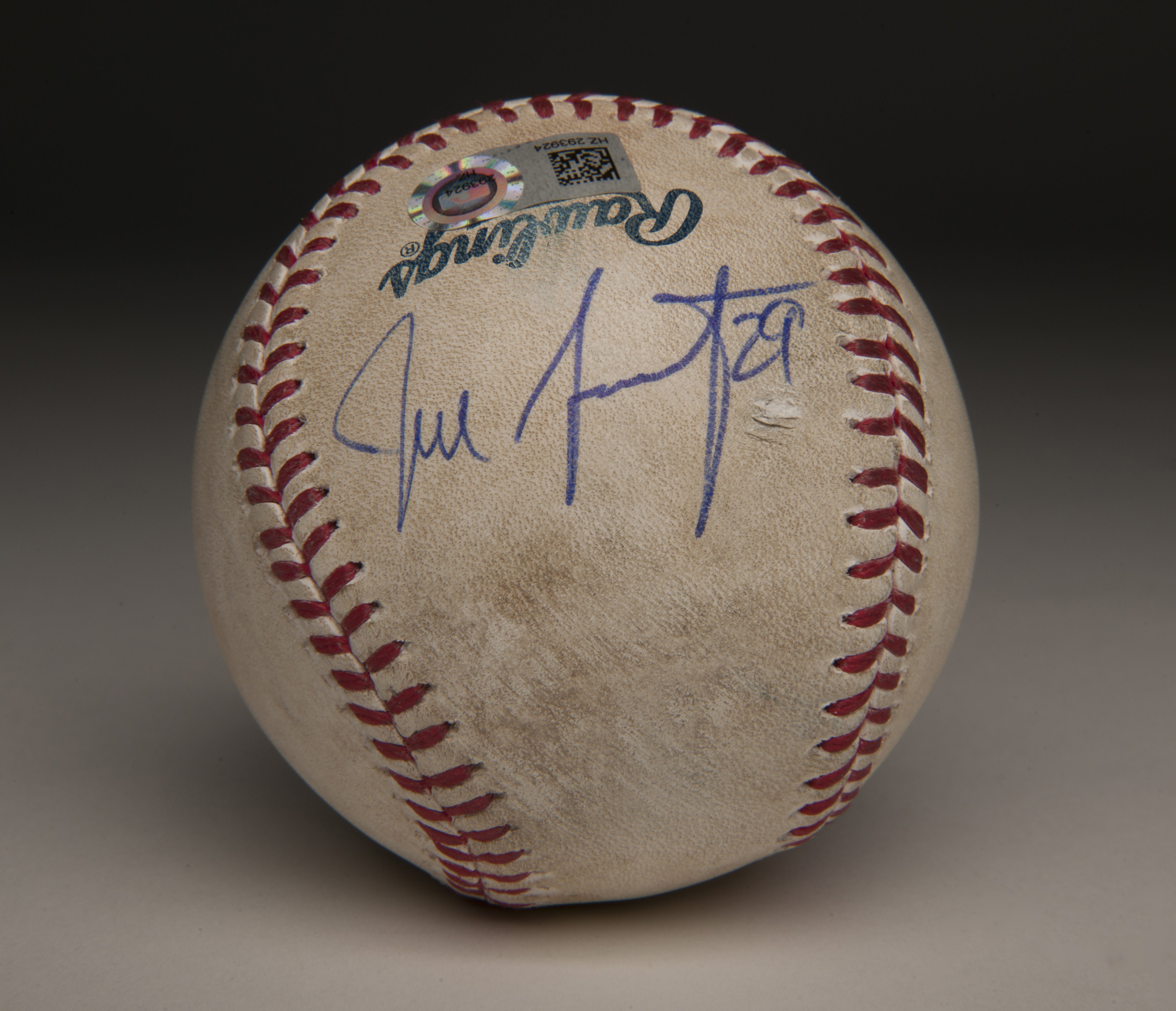

As it stands now, Washington Nationals pitcher Reynaldo López is the answer to the trivia question: Who threw the final regular-season traditional intentional walk?

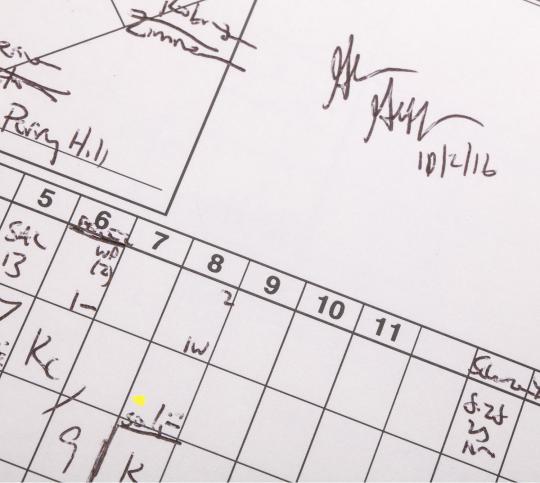

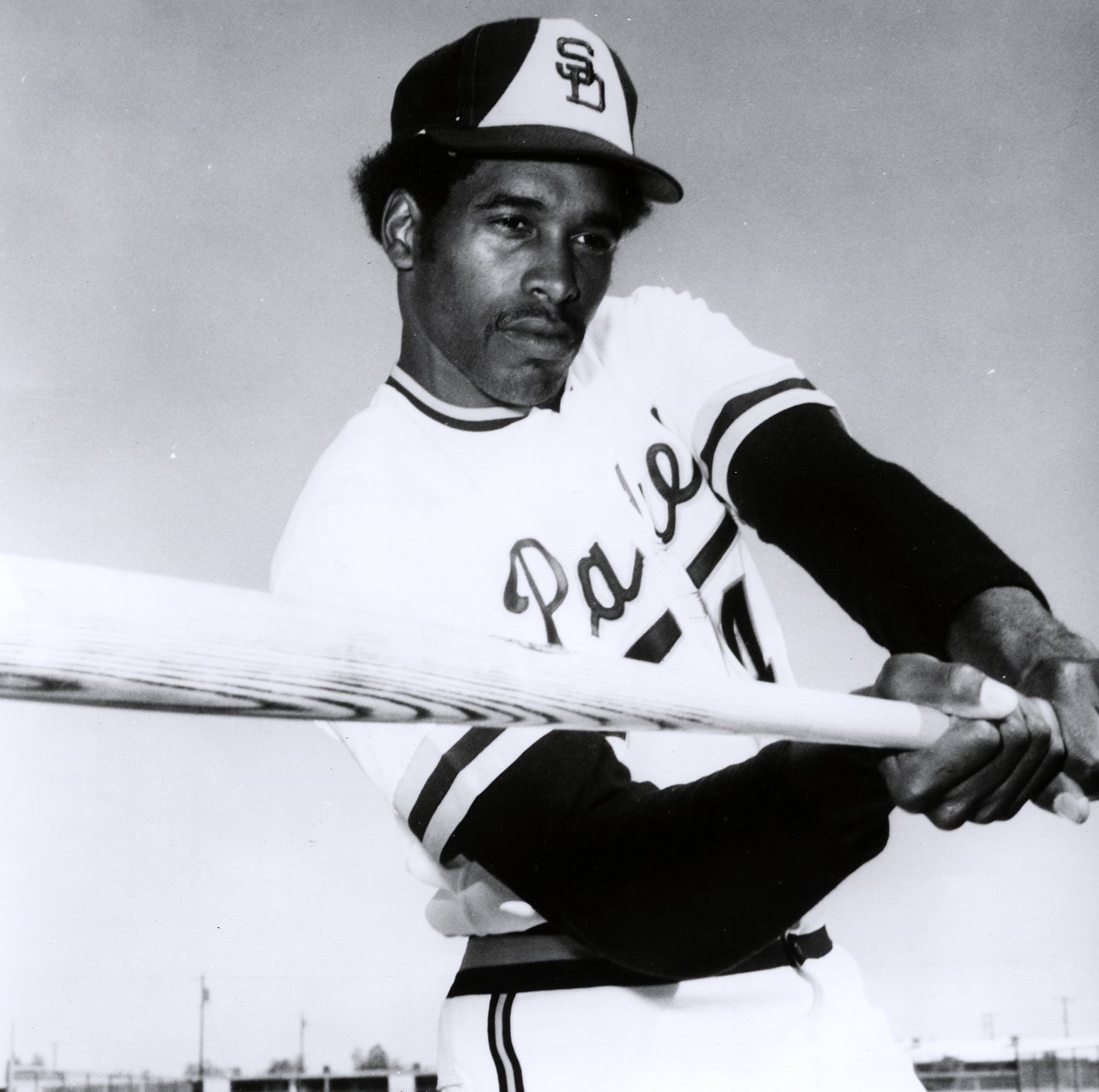

The event took place on Octo. 2, 2016, the last day of the regular season, with the Miami Marlins at Nationals Park. In the top of the eighth inning, with two outs and runners on second and third, Washington’s right-handed relief pitcher López intentionally walked the righty-swinging slugger Giancarlo Stanton, who was pinch-hitting, to load the bases. The next batter, catcher Tomas Telis, would single to right field, knocking in two runs in a game Washington would go on to win, 10-7.

“I hope they never change it [back],” Stanton later said with a smile.

To document the historic occasion, Glenn Geffner, a radio broadcaster for the Marlins, donated the scorecard he kept of the game to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Miami’s Justin Bour, who received on intentional walk a few innings before Stanton’s, later told the Sun Sentinel, “I know there’s been a couple of games won or lost on [intentional walk flubs], but I know [MLB is] all about speeding up the game. We’ll see how it goes.”

In 2016, there were 932 intentional walks in 2,427 regular season games, one every 2.6 games or an average of 0.38 per game.

A pair of longtime big league skippers expressed no apprehension with the new intentional walk initiative, with Cleveland’s Terry Francona saying, “It doesn't seem like that big of a deal. I know they're trying to cut out some of the fat. I'm OK with that."

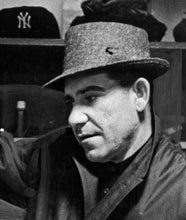

Yankees manager Joe Girardi said: "You signal. I don't think that's a big deal. For the most part, it's not changing the strategy, it's just kind of speeding things up. I'm good with it."

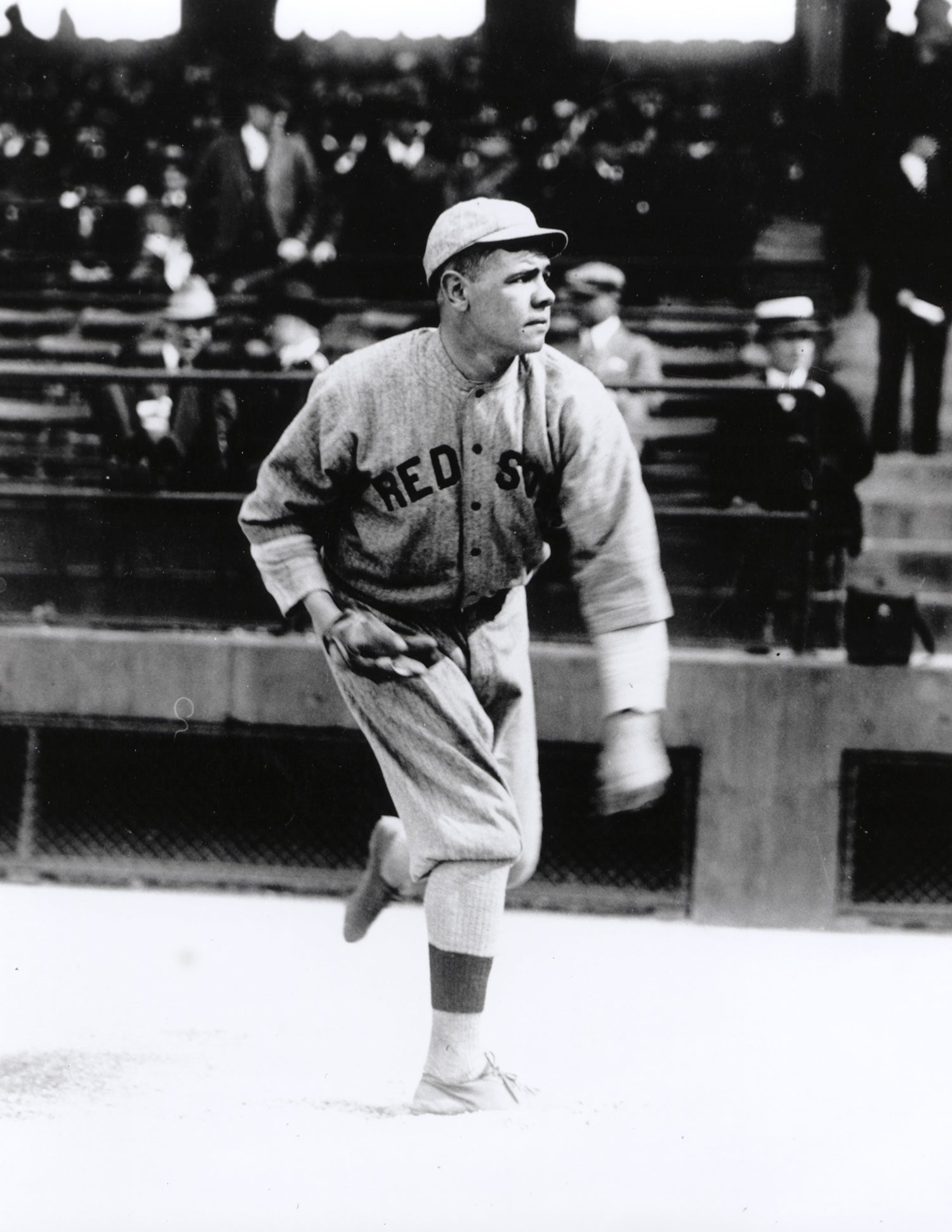

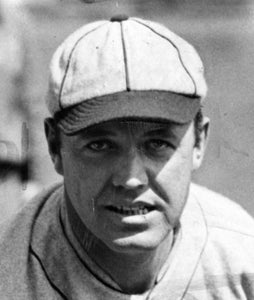

Modern research shows the intentional walk dates back to at least the 1870s. The maneuver has over the decades engendered criticism (Grace Coolidge, wife of president Calvin Coolidge and a baseball fan with strong opinions, once proposed to abolish the intentional walk) and controversy (Hall of Fame pitcher Burleigh Grimes’ purported idea of an intentional walk is four pitches at the batter’s head).

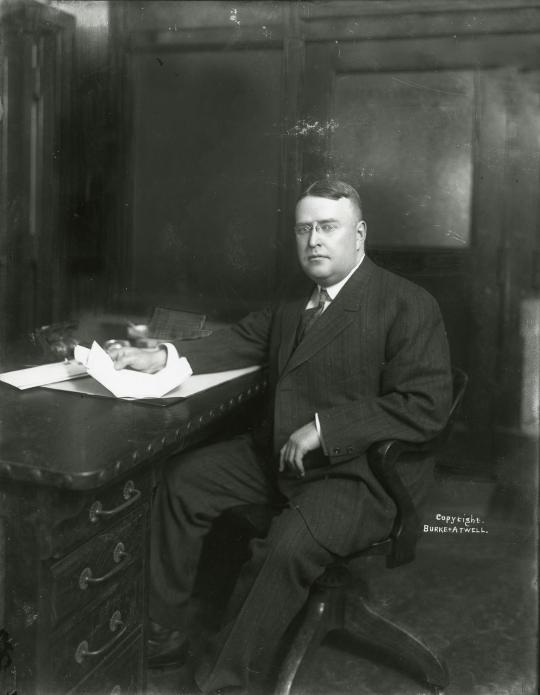

“The intentional base on balls has come to be one of the most, if not the most, unpopular plays in baseball,” said A.L. President Ban Johnson in 1913. “The great majority of the game’s patrons seem to oppose it. So do I, but what are you going to do about it?”

In 1956, the Junior Circuit wanted to speed up its circuit’s games, which had gone from averaging 1:58 in 1943 to 2:31 in 1955.

“We feel that the lengthening time required for completion of our games is a serious problem that must be dealt with in order to keep baseball interesting and attractive to the fans,” said A.L. President Will Harridge, expressing a theme that could come right from the lips of the leaders of today’s game.

“What specifically can be done about it we don’t know yet. Nevertheless, we are going to explore every possibility.”

The eight-team A.L, which saw 312 intentional walks during the 1955, decided to experiment with sending batters immediately to first base without tossing four intentional walk pitches during 1956’s Spring Training.

“This is purely an experiment, but I believe it will be a most interesting one,” Harridge said. “Would we try it in regular season play? Well, let’s just see how it works out in spring training first.”

Writing in the New York World-Telegram & Sun in February 1956, Dan Daniel, a 1972 J.G. Taylor Spink Award honoree, claimed that baseball men in general were not very enthusiastic over the AL’s announced training season automatic pass experiment.

“The Harridge circuit has decided to try out the scheme of the pitcher notifying the plate umpire whenever he wishes to walk a batter intentionally,” Daniel wrote. “The umpire then will wave the batter to first base, and that will be that, without the formality of the pitcher throwing four bad ones.

“The National League has refused to have anything to do with this scheme except in the spring exhibition games with AL clubs. The idea is not exactly new. It has been advocated for some 20 years and, in the past, ridiculed with vehemence by the league which now is going to give it a try.”

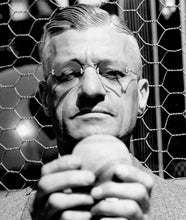

George Weiss, the Hall of Fame general manager of the Yankees, made his strong thoughts known: “It is not a good idea because it goes against baseball tradition, tends toward mechanization, and takes away from the suspense of the game. If the fans holler, well, that’s their right. I don’t like the experiment one bit.”

In an editorial in the Sporting News in March 1956, the “The Bible of Baseball” expressed dismay at this slight alteration to baseball tradition.

“This is an absurdly small gain to make in view of the fact that abolition of the four-pitch walk would remove from the game a small but colorful tradition.

“There’s a bit of drama in the picture of a Williams or a Berra or a Mantle standing helplessly in the batter’s box, while the opposing manager tells him in actions which speak louder than words: ‘You’re too tough. In this situation, we can’t take a chance on pitching to you.’

“Here’s hoping that, when the Spring Training experiment is over, we’ll still see such drama. Much of baseball’s popularity depends on its allergy to change. A change in the intentional pass rule would seem to have little point.”

By the end of Spring Training the results showed the experiment had flopped, with many clubs not even bothering with it during its exhibition games. “I don’t like it,” says Detroit skipper Bucky Harris, who ordered his Tigers pitchers to make the four wild tosses. “It takes too much out of the game.”

Earl Hilligan, chief of the A.L.’s Service Bureau, added, “As far as I know – and I saw a lot of games – not one manager experimented with the idea. Our managers were told the thing was strictly voluntary. They didn’t have to use it. Evidently none of them wanted to use it.”

The National League president at the time, Warren Giles, would later share his unique theory on why the A.L.’s experiment was so short lived.

“The American League,” said Giles, “has deprived its fans of four chances to boo on every intentional walk. Booing is a pleasure that every fan is entitled to.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum