- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Star-spangled jersey

#Shortstops: Star-spangled jersey

In October 1917, the world was in uproar: A war was being waged, bringing in nations from all over the world – with millions dead in the three years since it began. The United States had abstained from entry into the conflict until earlier that year, when it was revealed that German forces contacted Mexico, attempting to bribe them into the war against the United States.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

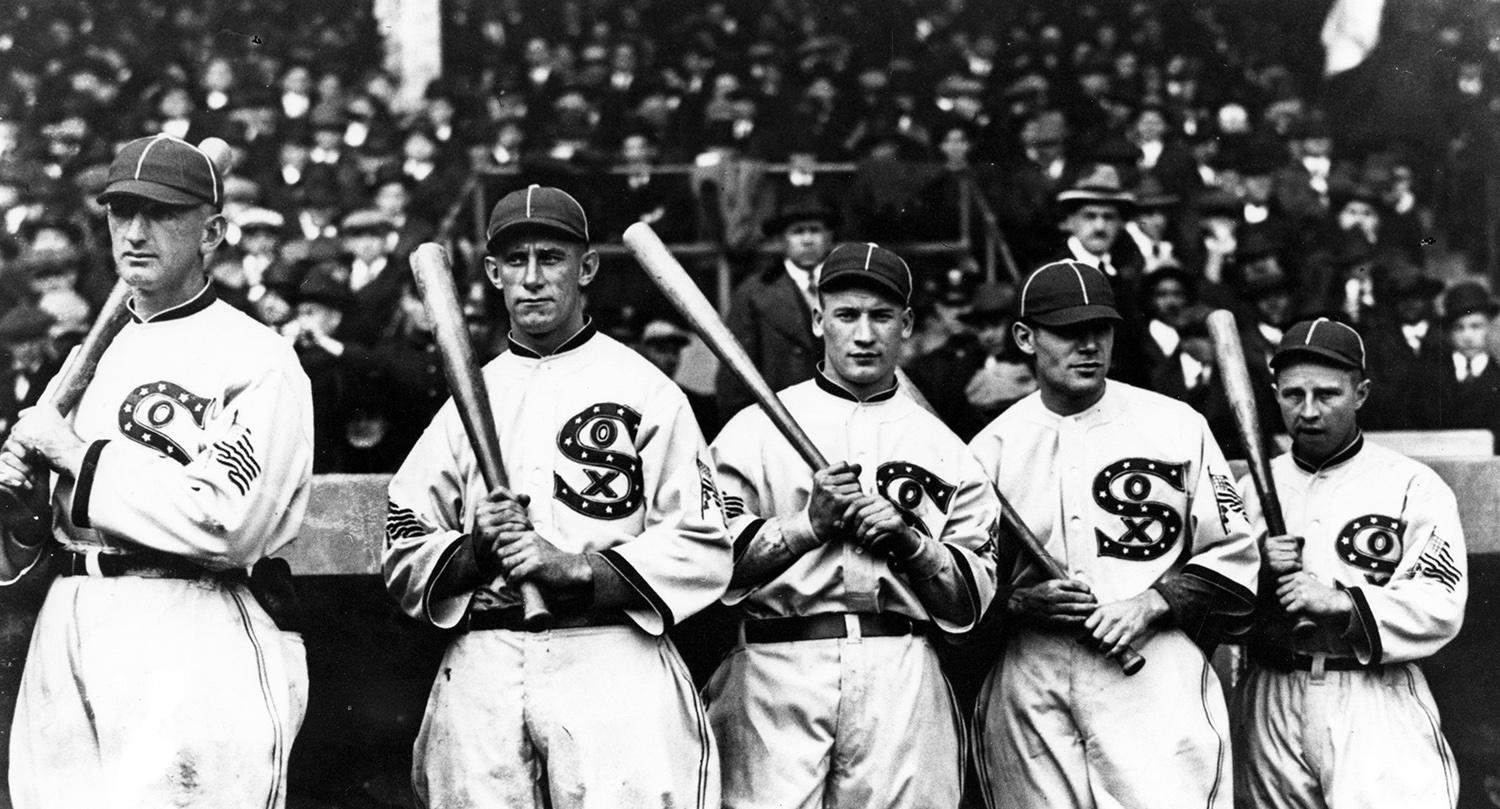

A bright spot amid the political tension was the Chicago White Sox, who seemed nearly indomitable. The team finished the season with a 100-54 record, a winning percentage of .649, which is a franchise record intact to this day. Their pitching staff, including the fiery knuckleballer Eddie Cicotte, spitballer Red Faber and the powerful southpaw Lefty Williams, led the league with a 2.16 ERA and could quickly and easily vanquish opponents. Their defense was sharp for the occasions that a ball did get hit with fielders like Shoeless Joe Jackson, Happy Felsch, Eddie Collins, and Chick Gandil, all of whom also made up a powerful offense which led the league in runs.

But this juggernaut could not keep the political climate out of their sport. When the White Sox appeared in the World Series, they wore patriotic uniforms to show their support of the war effort. Instead of their typical black logo, the white wool jerseys sported their signature “Sox” on the breast in blue text, outlined in red and white with stars along the shape of the letter S.

They also wore two American flag patches, one on either sleeve. This is one of the earliest special occasion uniforms worn in the major leagues, and among the first to support a political, military effort. These jerseys brought outside current events inside the stadium, rather than leave the worlds separate.

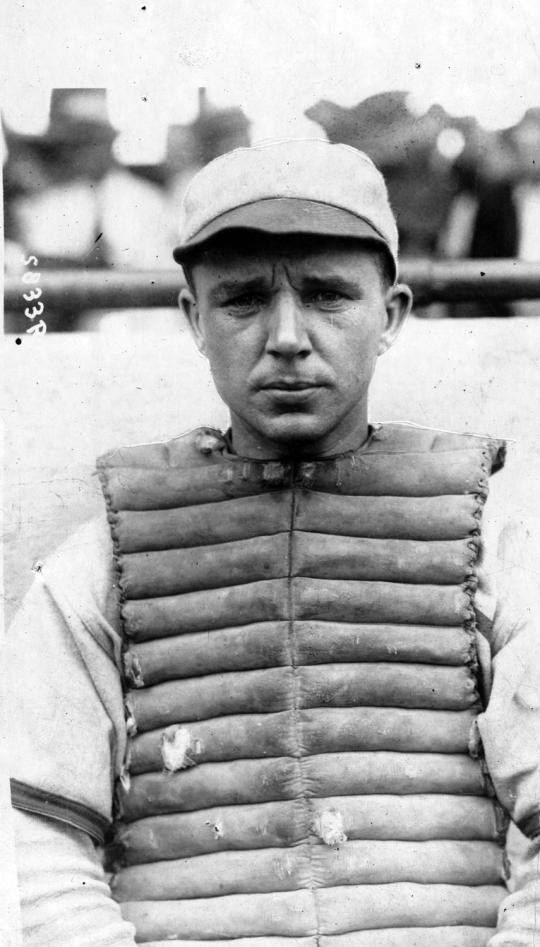

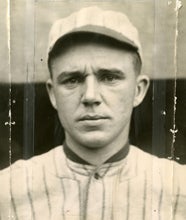

This particular jersey was worn by future Hall of Fame catcher Ray Schalk. Born in 1892, he joined the White Sox just shy of his 20th birthday in 1912. The baby-faced backstop quickly took a commanding role in the clubhouse when he proved to be an extremely capable defensive player. Small, agile, and powerful, he was a force to be reckoned with on the diamond. And his dependability was legendary: In 12 of his 18 major league seasons, Schalk caught more than 100 games, 139 of 154 in 1917 alone.

With his keen knowledge of his pitchers’ abilities and of the rest of his team, Schalk knew something was amiss during the World Series in 1919 when his bullpen was throwing sloppily and not listening to him. A year later, the catcher was recognized as one of the “immaculate” White Sox uninvolved in what headlined as the Black Sox Scandal, where eight players were accused of intentionally throwing the World Series.

The scandal, which shocked the nation as among the biggest infringements on baseball’s integrity, sobered fans to the reality that the world outside the stadium could step into America’s pastime quickly and heavily. Acknowledging the brutal war abroad and those that had already stepped up to fight set a precedent for teams to address conflicts affecting their local and national communities. Today, major league teams regularly wear special uniforms for Memorial Day and Independence Day, and clubs fundraise and support social causes like fighting cancer, supporting at-risk youth, and aiding recovery efforts for communities struck by tragedy, like this year’s drives for victims of hurricanes Harvey and Maria. The teams are not isolated from these events, but experience them and therefore address them to show support for the communities that support them. Baseball as a community has a century long tradition of giving attention, support, and voice to moments of difficulty and conflict in our nation’s past.

Peyton Tracy was the registrar at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum