- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Atlanta Mystery Solved in Cooperstown

#Shortstops: Atlanta Mystery Solved in Cooperstown

In William Shakespeare’s "Romeo and Juliet", Juliet asks, “What’s in a name?”

For Baseball Hall of Fame curator emeritus Ted Spencer, the name of Norman Ladelle Brown has led to almost 25 years of research, acquaintanceship and answers to baseball mysteries.

Unlike Shakespeare’s tale of medieval-era, star-crossed romantics, the connection between Spencer and Brown started on Memorial Day of 1995 when the Museum’s Baseball Enlists exhibit debuted. The exhibit explored baseball’s involvement during World War II, from ballplayers who joined the armed forces to the women taking their roles on playing fields in various parts of the country.

One of the features of the exhibit was a list of the major leaguers and Negro Leaguers who had served their country during the war.

“One of the things we wanted to do,” Spencer recollected, “was to illustrate the drain of talent in the majors during that four-to-five-year period. … It was about 590 guys – 500 left the majors and the other 90 (that) we know of left the Negro Leagues.”

It was on that list that one of Brown’s son’s neighbors had seen the hurler’s name listed.

“About a month or so after the exhibit opened, I got a call from this guy saying that his neighbor had been up here on vacation and thought he saw (the caller’s) father’s name on the wall,” Spencer noted. “I said, ‘What’s your father’s name?’ and he said, ‘Norman Brown.’

“He said, ‘Could you take a picture of dad on the wall so that it’d be great for his grandchildren to have a picture of their grandfather’s name on the wall in the Hall of Fame?’ and I said, ‘Sure.’”

Spencer proceeded not only to send the photo to Brown’s son, Rocky, but also offered a copy of the materials in Brown’s clipping file from the Hall of Fame Library. He said the Brown family was thankful and “that was the end of it” – to that point.

Brown, who passed away on May 31, 1995, just days after Baseball Enlists opened, was born in 1919 in Evergreen, N.C., but lived most of his life in South Carolina. He pitched in professional baseball for over a dozen seasons, coming along in the Boston Red Sox farm system, where he was seen as a top prospect. Brown tossed a 3-0 no-hitter for Rocky Mount (N.C.) against Portsmouth (Va.) on July 16, 1940. In 1941, Heinie Manush, who managed Brown in Rocky Mount, claimed his pitches were “as fast as any pitcher in base ball, including Feller and Newsom.”

Herb Pennock, who also coached Brown, said the righty possessed “blinding speed.”

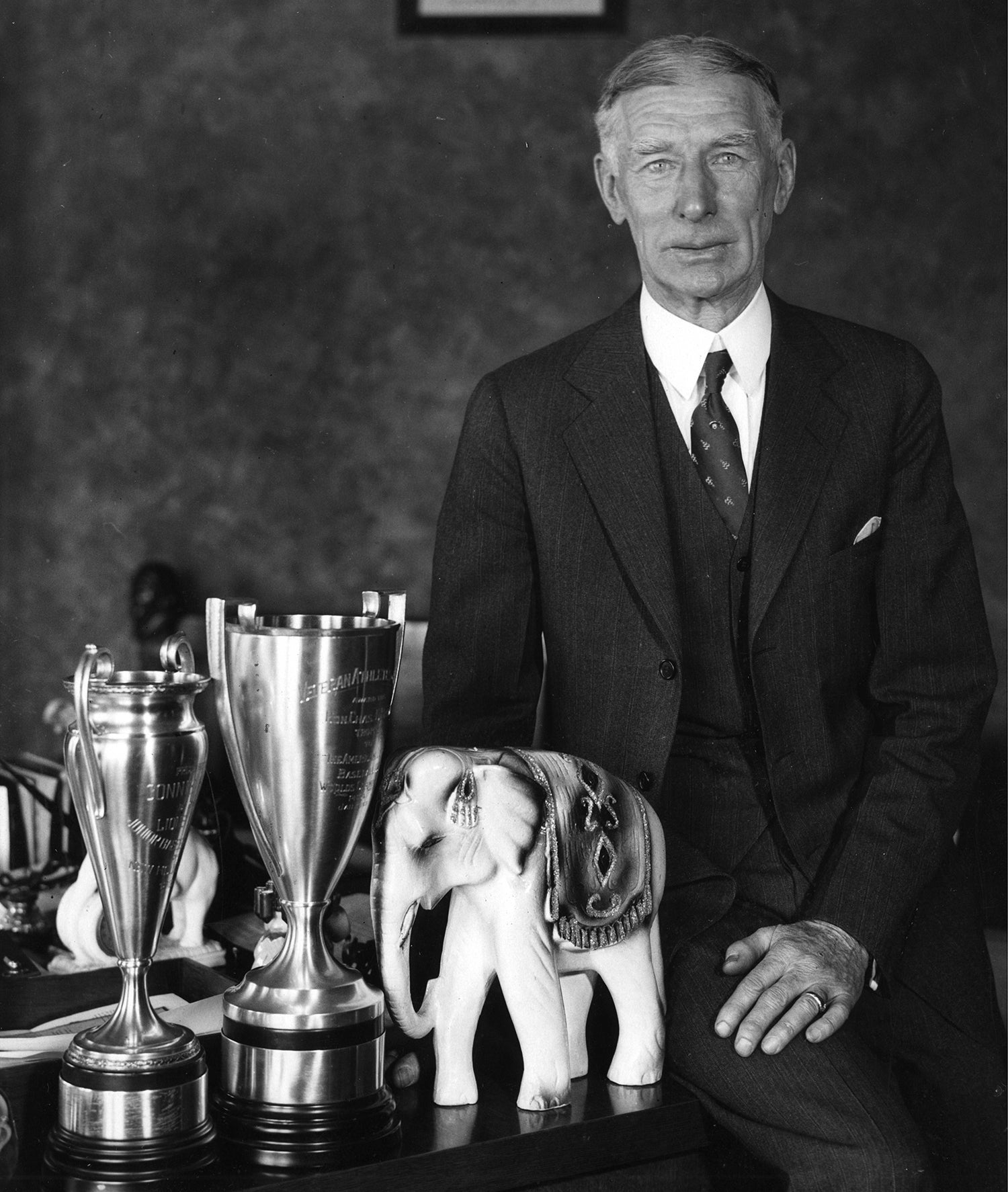

Despite that promise and advancing to the highest levels of the Red Sox minor league system, Brown was traded to the Philadelphia Athletics on Sept. 27, 1943, one of a flurry of deals the A’s made that day. The 1943 A’s, firmly ensconced as the doormat of the American League, went into the season finale against Cleveland on Oct. 3 with a 49-104 record. With nothing to lose, skipper Connie Mack decided to go with Brown on the mound.

In his major league debut, Brown went seven innings, allowing four runs – all unearned thanks to fielding errors – on five hits and struck out one batter. He left the game with the score tied, but the A’s fell 8-4 when reliever Carl Scheib gave up four runs in the top of the 11th inning.

Connie Mack had called for Brown. Now it was Uncle Sam’s turn.

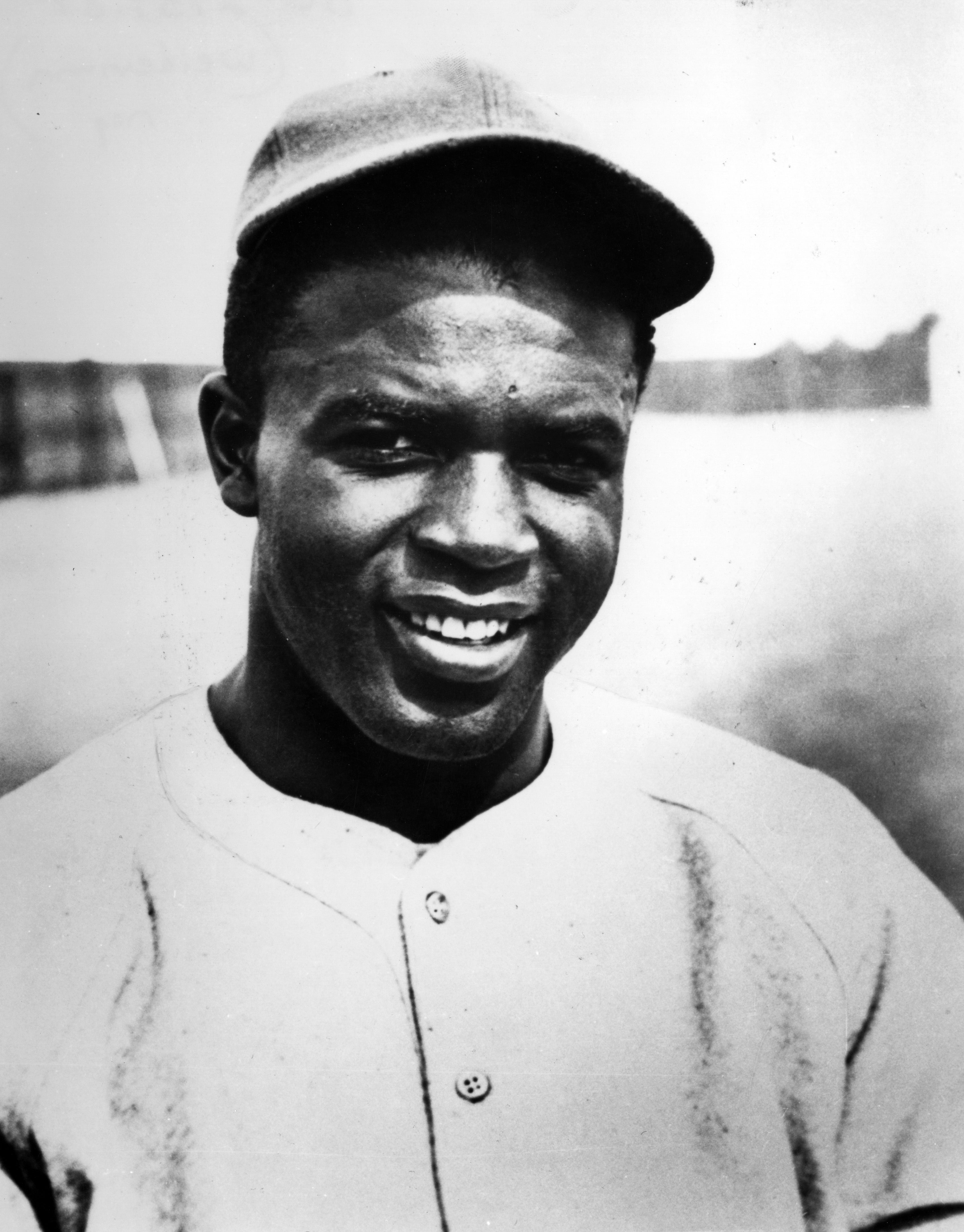

Jackie Robinson of the Dodgers waits on deck to face pitcher Norm Brown of the Atlanta Crackers in this April 10, 1949, photo from the Hall of Fame's Photo Archive. The photo, which features Duke Snider batting, was identified after a chance connection between Brown's son and Hall of Fame curator Ted Spencer. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Brown enlisted at Fort Jackson, S.C., in Jan. 1944 and was discharged in Sept. 1945, missing the 1944 and 1945 baseball campaigns to serve in the US Army. He returned to the major leagues in 1946, but only appeared in four more games for the Athletics before spending the remainder of the year – and his pro career – in the minors. Brown went 0-1 with a 6.14 ERA in 7.1 innings of work that season.

After a couple of tough seasons spent with the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Triple-A International League, Brown settled down in 1948 when he joined the Atlanta Crackers of the Double-A Southern Association. He must have found comfort in the south, as he went 22-14 in 1948 after going 12-20 in Toronto the previous two years combined.

Little did he know he would take part in Atlanta history just before the 1949 regular season started.

That is where Spencer and Brown would intersect once more.

“Fast forward to about 2008, (Hall of Fame senior curator) Tom Shieber gives me a call and says, ‘I found this photograph. … I can’t figure out what it is. I want you to look at it,’” Spencer said.

The photograph, one of many in the Hall of Fame collection which lacks some detail and background, featured a somewhat large ballpark, whose stands were overflowing with fans.

“It’s a pretty big park. To not know that park is really a mystery,” Spencer remarked. “So Tom says, ‘Look who’s on the on-deck circle.’ I look down and say, ‘Holy [cow], that’s Jackie Robinson!’ He says, ‘It’s the Dodgers, but I don’t know where they are or who they’re playing.’”

Shieber then pointed out some the signage in the photo. Beyond the perimeter fence atop the bluff in right field are signs for two businesses: Frick Co. Machinery and Stodghill and Company Textile Chemicals. Knowing the city in which these businesses were located – and where they were located within proximity to each other – could be the key in unlocking one part of the mystery photo.

A few days later, Shieber had put the clues together to solve the conundrum.

“In those days, when teams broke camp to come north, to stay fresh and promote a minor league club, would play a weekend series somewhere along the way,” Spencer said. “[Shieber] says, ‘This is Ponce de Leon Park and the Dodgers are playing the Crackers and it was a three-game series. And the guy pitching for Atlanta is some guy named Norman Brown.’”

To be more specific, the date was April 10, 1949, and this was the rubber match of a three-game series the Dodgers played in Atlanta at Ponce de Leon Park, a ballpark famous for its grand magnolia tree in right-center field. Brown pitched a complete game for the Crackers in their 8-4 victory over Brooklyn. Even more important was that this series marked the first integrated baseball games held in the state of Georgia, just under 250 miles from Cairo, Ga., Robinson’s birthplace.

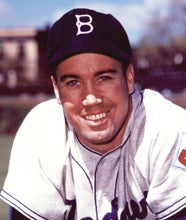

In the photo, Duke Snider is batting as Robinson waits on deck.

Paid attendance for the three-game series, played despite threats by the Ku Klux Klan, was 49,299, a new record for Atlanta. More than half of the fans that Sunday were African Americans there to see Robinson perform.

“Jackie drew war whoops from the Negro sections in the outfield with a double and a single and two scores,” an Associated Press report claimed. “The big thrill for them was Robinson’s steal of home in the second inning.”

Despite the KKK’s threats, the AP noted “[t]here was no unfriendly demonstration of any kind for Robinson except for a few scattered boos on his first appearance at the plate.”

New York Daily News sportswriter Dick Young reported the scene at Ponce de Leon Park:

The sight of the swarming humanity was incredible. In addition to the heavy overflow of whites in the left-field foul territory Negro fans fringed the vast outfield, covered the steep 50-foot hill that rises from deep center field, and even were perched by the scoreboard on the four-tier, terraced billboards in right field. Hundreds of non-paying spectators on hills outside the park actually were closer to the action than many of the cash customers on the peak of the incline in distant center.

Judging from the photograph, Young’s description is quite accurate. In the sixth inning, umpire Jocko Conlan ejected Snider after the former claimed Snider’s catch was deemed out of play due to the crowd on the field. Snider heartily disagreed with Conlan’s assessment of where the playing field began and the crowd ended, thus earning his banishment.

When Shieber identified the game in question in the photograph, Spencer went into action.

“I’ve got to get a copy of that picture,” Spencer remembered saying, “because somewhere in this country there’s a guy who really needs this picture.”

It had been over a dozen years since Spencer was last in touch with Rocky Brown, and he was having difficulty finding Brown’s contact information. Spencer thought Brown might have lived in Western Massachusetts. Letters sent to Norman Browns west of Worcester came up empty. As time passed, Spencer continued to think about the photo every once in a while. Eventually, he decided to take another look at Norman Brown’s file, which contained the pitcher’s obituary and therefore, Rocky’s location as of 1995, Bennettsville, S.C.

Spencer reached out to Rocky Brown but instead spoke to Brown’s wife. She said it was “awesome” that a photo was found, and even better, Rocky’s birthday was the following week and a photo would make a great present. Spencer overnighted the photo to ensure it would arrive on time.

Spencer said Rocky Brown “was absolutely thrilled.”

Norm Brown would pitch for the Crackers in 1949 and for multiple other teams before wrapping up his career in the mid-1950s. Ponce de Leon Park was demolished in 1967, after the Braves moved into town, and the site is now a shopping center. However, the buildings behind the perimeter fence, which housed Stodghill and Company and the Frick Co. are still in existence, as are the magnolias.

And yet, the story still does not end there.

Not more than a year or two ago, Rocky Brown contacted Spencer about some goings on in Bennettsville, which is roughly halfway between Charlotte and Myrtle Beach.

The town had received funding to develop some land near the town offices into a city park. However, the undeveloped land stood next to the town’s old ballfield, and the plans were to raze the ballfield and incorporate it into the park. Rocky Brown wanted to know whether the field had any professional history to it.

As it turns out, the old ballfield is located, conveniently enough, on Ball Park Street in Bennettsville, a town of just over 9,000 residents.

Spencer consulted with Hall of Fame researcher Bill Francis, who determined that various Eastern League teams held spring training in Bennettsville in the 1940s and 1950s. Spencer then forwarded that information to Rocky Brown.

Checking in with Brown earlier this year, Spencer learned that money earmarked for the park was needed elsewhere, placing the project in limbo for the time being. Spencer checked in again with Francis to locate some more information.

“There was an article saying that the chamber of commerce was in a tizzy because … the Phillies were going to play an exhibition game and (Robin) Roberts and (Richie) Ashburn and (Willie) ‘Puddin’ Head’ Jones … were going to appear. I said, ‘That’s just what we need,’” Spencer remarked. Jones, who played 13 seasons for the Phillies, was born in nearby Dillon, S.C., and a solid drawing card.

The ballpark, known in 1954 as Carrol Field, was filled to capacity as the Phillies became the first major league club to play in Bennettsville, downing their minor leaguers, 7-5. Ashburn and Jones both played.

A few more relevant articles were found by Francis. Spencer sent those over to Brown, as well.

Most recently, Brown forwarded photos of the ballpark during the flooding the region endured after Hurricane Florence this year. Only the dugout roofs and foul poles were visible.

“Because we were able to give them this information and these dates, that’s now energized the publisher of the local newspaper,” Spencer said. “Now the publisher and editor are energized to go into their own archives and do some work … to lay out the story that there is some significant baseball history in a town that size.”

“There are a couple of things to take away from this,” Spencer continued. “This is what we do, and everybody’s important.

“This is what organizations like us do. … It isn’t just about the exhibits in the Museum. It isn’t just about the exhibits at a historical society. It’s what we do and the scope and the great value of it.

“You go into this business, you’re not going to get rich. But you’re certainly going to be enriched.”

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum