- Home

- Our Stories

- The Sporting News brought baseball to the world

The Sporting News brought baseball to the world

"When baseball wanted to speak, the Sporting News cleared its throat.” –Bill James

Back in the 1920s Jack Potter, whose father had owned the Phillies, was on board an ocean liner in port at Le Havre, France, when he spotted a familiar figure returning from a European vacation with his wife.

He turned to the ship’s captain next to him on the bridge and pointed. “There is the man who wrote the Bible.”

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Who is he, Matthew, Mark, Luke or John?” the captain asked.

“That’s Taylor Spink, and he writes the Bible of Baseball.”

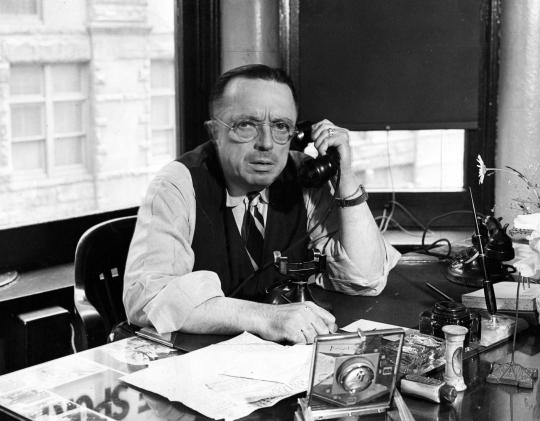

Such was the renown of the Sporting News during the height of its powers under the leadership of J. G. Taylor Spink.

His uncle Al had started the sports weekly in 1886 but his interest strayed to the theater. Al’s brother – Taylor’s father, Charles – assumed leadership in 1890 and within 20 years had devoted the Sporting News’ coverage exclusively to the emerging National Pastime, its masthead declaring: “Official Organ, National Commission, Authority of Game.”

By the time of Charles’ death in 1914, Taylor, who had worked at the paper for five years, inherited a publication of influence embedded in the game’s hierarchy. Ban Johnson, American League president, and Charles Comiskey, White Sox owner, were pallbearers at Charles’ funeral.

The 26-year-old Taylor, fearless and opinionated, hard-working and driven, set out to further the Sporting News’ influence, appeal and profitability.

One of his first moves was to hire correspondents from each city with a team in organized baseball to improve the depth of coverage for “The Base Ball Paper of the World,” the slogan that ran on the masthead. The Sporting News became the go-to source for fans and insiders alike, the only source for baseball news from around the country not found in local newspapers.

“What we used to call ‘dope,’” said Steve Gietschier, who served as TSN’s archivist from 1986-2008. “It was the newspaper not only for fans but for those in the business, a trade paper like Variety or the Wall Street Journal when it concentrated on Wall Street.”

The paper frequently took stands on issues that affected baseball. When Secretary of War Newton Baker ordered an early ending for the 1918 season to make players available for military service, TSN complained: “Baker’s Order a Blow to Nation’s Morale/Not Only Civilians But Boys in Service Are Hot.”

In December 1919, the paper called for an inquiry of charges the World Series had been fixed, and Spink provided Ban Johnson with valuable leads that allowed him to prove the guilt of eight White Sox players.

The Sporting News campaigned against the Federal League, in favor of Sunday baseball, against the practice of leaving gloves and catcher’s equipment on the field and for the use of numbers on jerseys.

After the first All-Star game played in 1933, TSN advocated for MLB to make the game an annual event played in sites rotating among the 10 cities with teams. When the Reds installed lights at Crosley Field, the paper hailed Larry MacPhail, the team’s general manager, as a visionary and encouraged fans to give night baseball a chance. Initially against radio broadcasts of games – hopping the band wagon of fear that they would kill interest in newspapers – Spink shifted course and published a “Radio Log” listing nearly 300 stations.

Spink’s paper occasionally proved prophetic, as with the 1925 headline: “Gehrig’s Bat May Keep Pipp on Bench.” Also in 1925, eight years before the first All-Star Game, TSN polled 102 BBWAA members to select its first major league all-star team, which included future Hall of Famers Dazzy Vance, P; Walter Johnson, P; Mickey Cochrane, C; Jim Bottomley, 1B; Rogers Hornsby, 2B; Pie Traynor, 3B; Goose Goslin, OF; and Kiki Cuyler, OF.

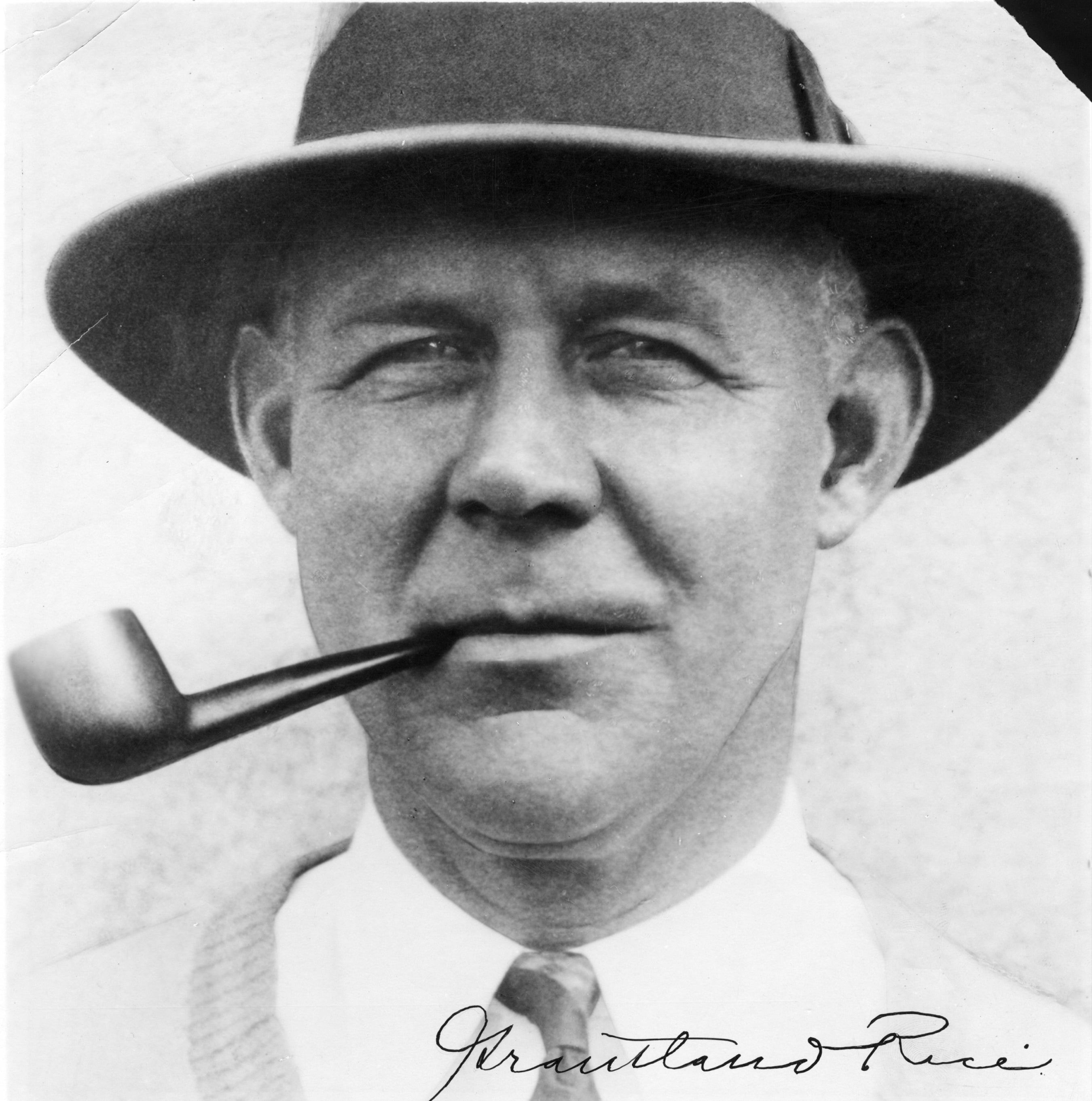

Many of the nation’s best sportswriters wrote for the weekly, including Grantland Rice, Dan Daniel, H.G. Salsinger, Dick Young, Bob Broeg and Jerome Holtzman. Damon Runyan contributed fiction. Fred Lieb’s byline was a constant for 60 years. Spink also employed former players like George Wright, a star in 1869 on the Cincinnati Red Stockings, who wrote highlights from the game’s history, and Al Demaree, who became a syndicated cartoonist after retiring as a pitcher in the National League. Billy Evans, an American League ump, penned a column.

Spink also commissioned photographs from Charles M. Conlon, the premier photographer of baseball players during the first half of the 20th century.

There are more than 8,000 negatives of his in the TSN archives, spanning four decades. Hundreds of other Conlon images preserved at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

The Sporting News dispensed much of its information in the form of regular columns, which included “Stove League Stories,” “Caught on the Fly,” In the Bull Pen,” “Deals of the Week” and “My Funniest Story” (told by players and managers). Readers could register their complaints in “Beef Box,” and the paper (which by 1930 offered the “Latest and Best Baseball News-Gossip”) dished on players’ wives. As early as 1910, three weeks after Rube Waddell’s marriage, the paper reported that his wife was in New Orleans while he was pitching for the Browns on the East Coast.

“Rube is too crazy for me,” TSN quoted her. “I’ve quit him cold.”

The weekly also featured poetry, serialized novels with prominent bylines–such as “Won in the Ninth” and “Pitching in the Pinch” by Christy Mathewson – and the serialized life stories of players like Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins and Honus Wagner.

But box scores were long the backbone of the Bible of Baseball. Since its inception, it ran the box score of every major league game played – triple-checked for accuracy. In the 1920s, after it added the box scores from 12 minor leagues, the statistical summaries filled more than half of its pages (six to seven of 10 total). The box scores were a portal into the games played around the country, and the Sporting News, an early aggregator, the only source.

The addition of minor league box scores boosted circulation. “A lot of subscribers in minor league towns were starved for baseball news,” Gietschier said.

During The Great War, Spink worked out a deal with the American League to purchase 150,000 copies at a discount and send them to G.I.s overseas. During the Depression, he came up with contests, such as a competition on who could provide the best advice to the National or American League president and predicting the precise standings on July 4.

When he offered lifetime subscriptions to the weekly for $25 in 1941, Private Hank Greenberg, stationed at Fort Custer, was one of the first to sign up. A 1942 crossword puzzle about Hall of Famers offered the prize of an all-expenses paid trip to Cooperstown and two World Series games in New York. Spink created The Sporting News Fans Club with Cincinnati pitcher Bucky Walters national president. For five dollars, members received a one-year subscription, copies of the Baseball Register, the Record book and free answers to 25 questions a year.

Spink also initiated awards. In 1936, the paper began naming its picks for the top executives, managers and players in the majors and minors. In 1947, after initially balking at integration, it established its own Rookie of the Year Award, and Spink flew to New York to present its first winner, Jackie Robinson (an “Ebony Ty Cobb”), with a watch.

Franklin D. Roosevelt had sent Spink a letter on the publication’s 50th anniversary in 1936, ending “I wish for it continued success in the service of the fans of whom I am one.” Spink ran the President’s letter on the front page. When FDR issued his “Green Light Letter” in January 1942, Spink printed it across three columns with the headline “Player of the Year/President bestows a Signal Honor–and Responsibility–on Game.”

“He knew if baseball goes out of business, the Sporting News goes out of business,” Gietschier said.

When Roosevelt died three years later, Spink hailed him as “Baseball’s Savior.”

In the fall of 1942, Spink sought to expand interest in the publication by adding coverage of other sports during baseball’s off-season, ending the weekly’s 32-year run devoted exclusively to baseball. By 1946, it started publishing an eight-page football weekly, The Quarterback, printed on peach-colored paper. The following year, it became an insert into TSN that changed to The All-Sports News when the season ended. But TSN continued to bill itself as “The Base Ball Paper of the World” as late as December 1960 even with large drawings of NFL quarterbacks on its cover.

When Bob Feller suggested to Spink in 1955 that TSN pick a player of the decade, he organized a 260-man panel of writers, executives and players who bestowed the honor on Stan Musial. (Ted Williams was selected in 1960, Willie Mays for the ‘60s, Pete Rose for the ‘70s.) Instead of a watch, Spink gave winners a grandfather clock.

In 1958, Spink opposed the way the Associated Press and United Press changed box scores from five columns listing at-bats, runs, hits, putouts and assists to four columns listing at-bats, runs, hits and RBI. He believed eliminating defensive statistics failed to tell the full story of a game. For three years at considerable expense, TSN converted box scores to the traditional format until finally capitulating in 1961.

It was perhaps a sign of the paper losing its influence in changing times. A year later, Spink, who had long suffered from emphysema, died of a heart attack. That same year, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America established the J.G. Taylor Spink Award for “meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”

Spink was the first winner, and all are honored in the “Scribes and Mikemen” exhibit at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Spink’s only son, Johnson – named after the former AL president – took over as editor and publisher following his death. Within a year, he changed the masthead slogan to “The Nation’s Oldest and Finest Sports Paper.” The number of box scores dwindled, and by 1968 only those from the major leagues appeared in its pages. Johnson cut some baseball columns and implemented new ones devoted to hockey, football and basketball. By 1972, he had put a thoroughbred, golfer, alpine skier, racecar and female tennis player (Chris Evert) on the cover, a sign that the Bible of Baseball had changed.

For decades, TSN had thrived without much competition. But in the ‘60s it had to contend with Sport and Sports Illustrated doing more extensive profiles and reporting behind the scenes of multiple sports. But television struck the fatal blow; box scores could not compete with live coverage in living color. At the same time, baseball had grown up into a big business. “It no longer needed the imprimatur of one publication for what it was doing,” Gietschier said.

The paper ceased print publication in 2012. But TSN’s legacy as the Bible of Baseball remains immortal.

John Rosengren is a freelance writer from Minneapolis