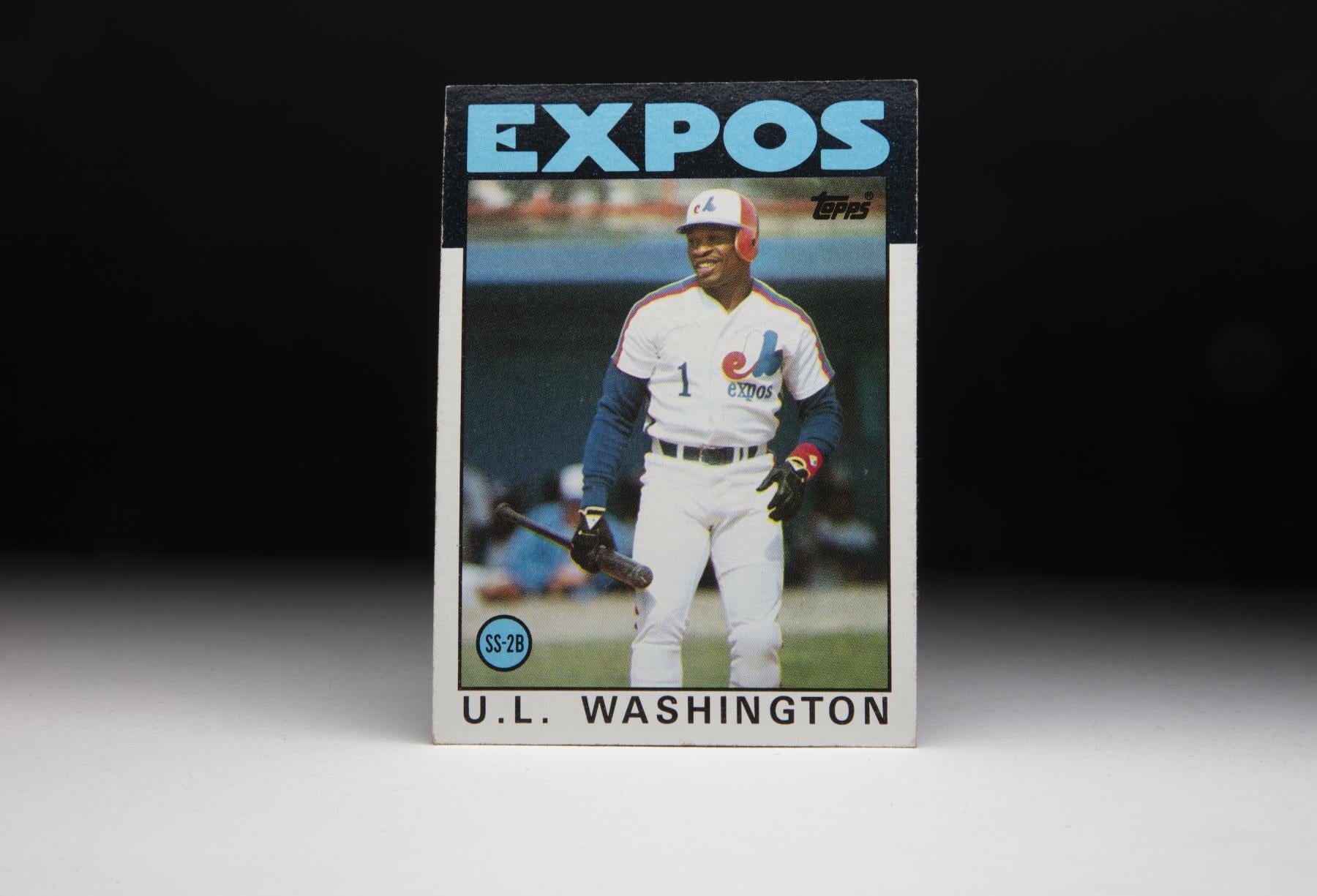

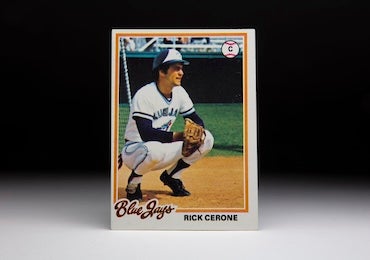

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps U L Washington

Baseball fans from the 1980s had a bevy of memorable stars to follow, ranging from future Hall of Famers to one-season wonders.

But few career .251 hitters are as recallable as U L Washington, whose ubiquitous toothpick gave him a permanent place in history.

Born Oct. 27, 1953, in Stringtown, Okla., U L Washington – the “U” and the “L” did not stand for other names but rather were his given identification; a relative shared the same name – starred in basketball and baseball in high school but went undrafted when his class graduated in 1971.

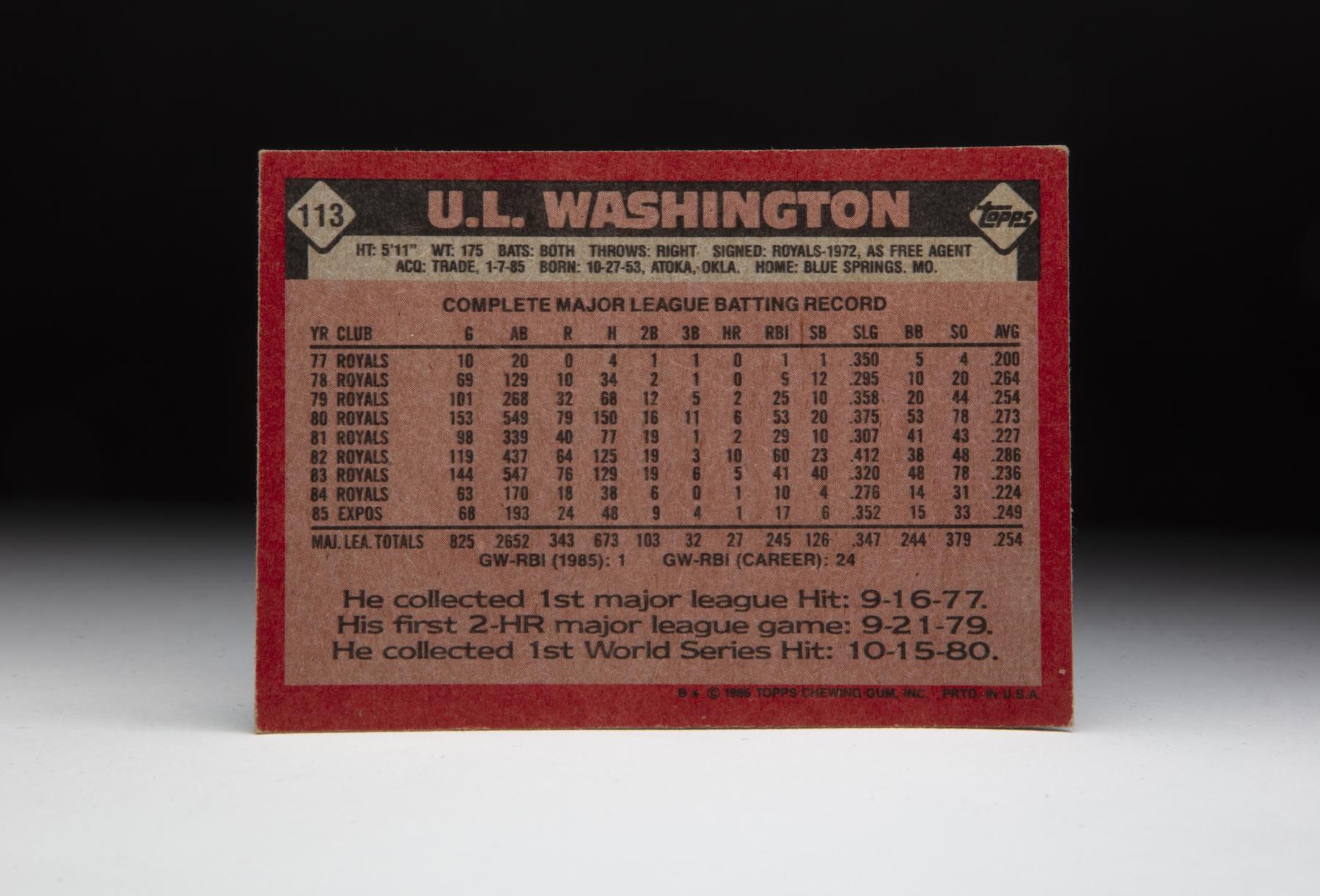

After attending Murray State College in Tishomingo, Okla., Washington heard from a brother about an open tryout for the Kansas City Royals in the summer of 1972. Washington reportedly saved money for bus fare and then traveled to Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, where he was the only player out of 275 hopefuls to be signed.

The Royals then sent Washington to their third class of their Baseball Academy in Sarasota, Fla., where he demonstrated range in the infield and a pesky bat. Eventually, Washington would become one of 14 graduates produced by the Academy over the five years it existed before it was closed in 1974.

Washington hit .283 with 51 RBI and 20 steals in his first season in pro ball in 1973 with Kingsport of the Appalachian League. He also made 36 errors over 68 games at shortstop but showed off the quickness that would eventually bring him to the big leagues.

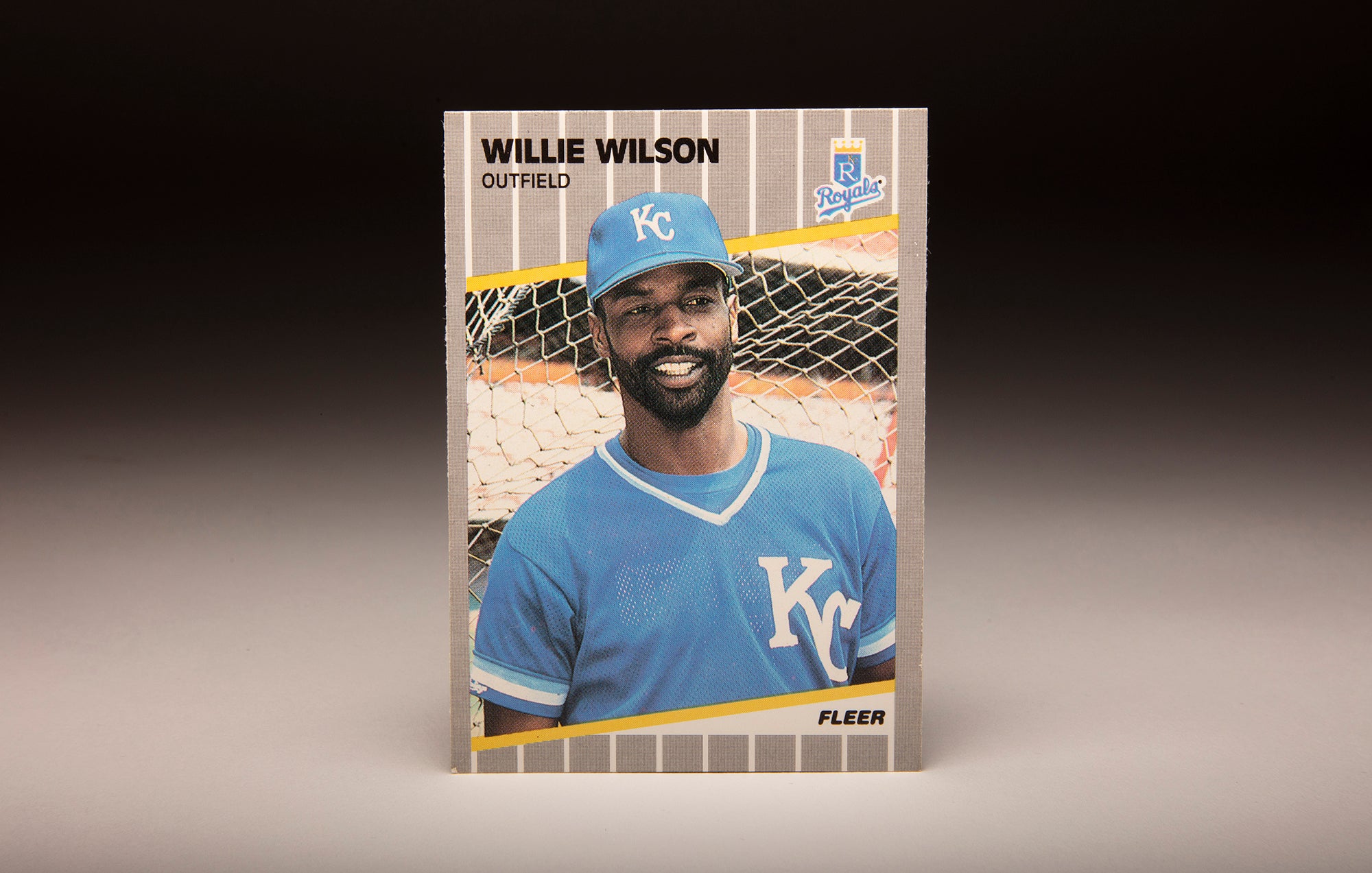

In 1974, Washington split time between Class A San Jose (a team that stole 372 bases, including 34 by Washington) and Double-A Jacksonville, finishing the year with a combined .252 average and 44 steals in 115 games. That performance earned him an invitation to the Royals’ big league Spring Training camp in 1975, and by the summer of that year – which Washington spent with Triple-A Omaha – Royals executive and future Hall of Famer John Schuerholz counted Washington as one of five “blue chip” prospects in the team’s farm system along with pitchers Mark Littell and Lew Olsen and outfielders Ruppert Jones and Willie Wilson.

Washington struggled at Triple-A to start the season but wound up with a .238 batting average and 22 steals in 128 games while making 46 errors at shortstop. The Royals, however, were unwavering in their believe that Washington would soon be in the big leagues.

“He has great speed, quickness and power,” Royals farm director Lou Gorman told the Salina (Kan.) Journal. “He’s struggling now but he has the basic ability.”

Following the 1975 season, the Royals encouraged Washington – a natural right-hander – to try switch hitting. But after a strong start to the season, Washington was limited to just 30 games in 1976 after suffering a broken leg following a collision at first base.

Washington returned to Omaha in 1977 but had impressed Royals manager Whitey Herzog during the spring, setting the stage for his eventual big league debut as a September call-up that year.

“We know that U L Washington has improved vastly,” Herzog told the Kansas City Times during Spring Training in 1977. “We’ll be able to bring him up from Omaha if we need a shortstop for more than a few days.”

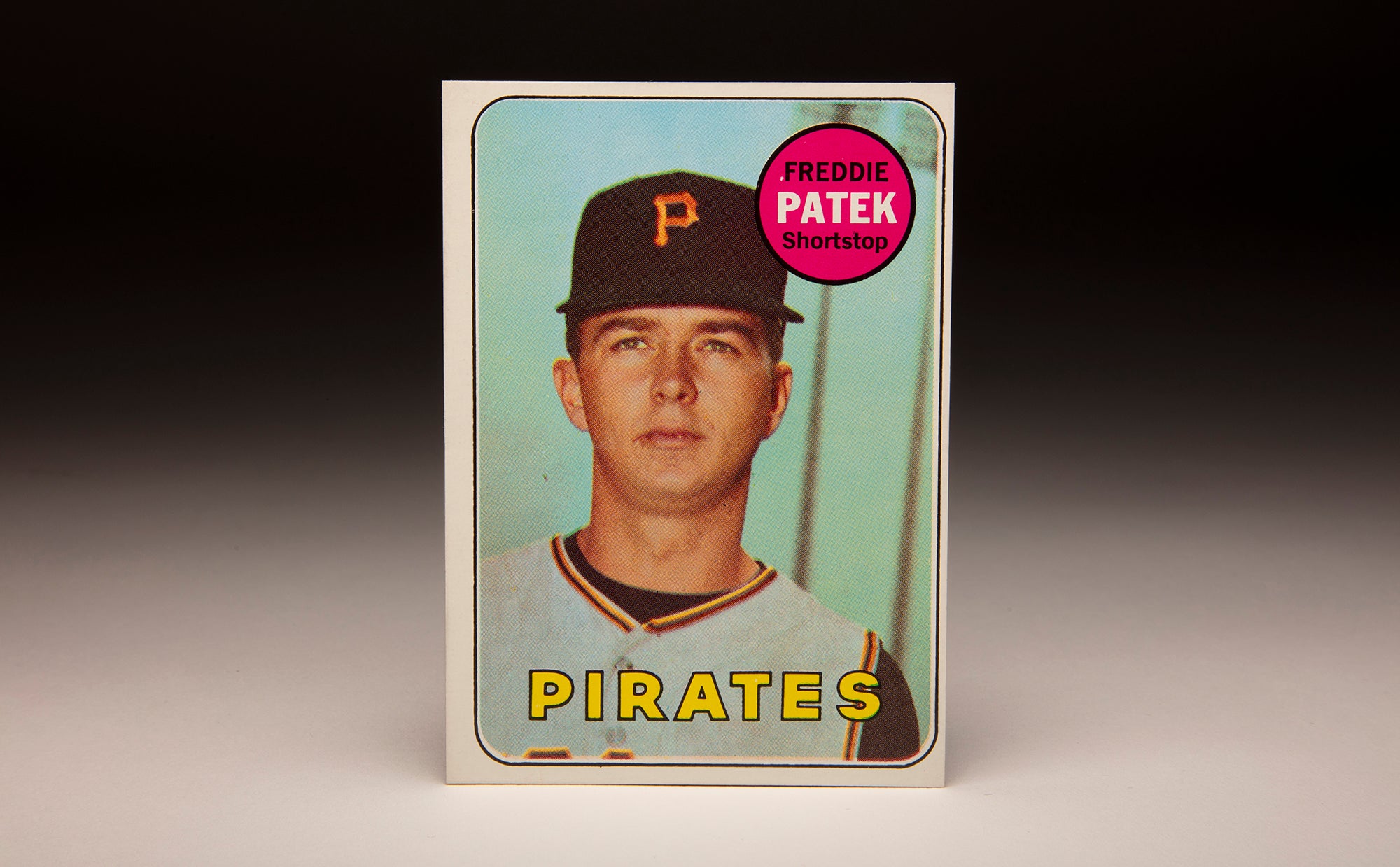

That scenario didn’t happen as starting shortstop Freddie Patek played in 154 games that year and led the American League with 53 steals. But Washington hit .255 with 39 stolen bases in 131 games at Omaha. He debuted with the Royals on Sept. 6 and played 10 games in September, helping Kansas City win its second straight AL West title. He made his first start on Sept. 16 against the Mariners, going 2-for-3 and teaming with Frank White, another graduate of the Royals Academy, as Kansas City’s double play combo. It would be the start of seven straight years where Washington and White would provide stellar defense up the middle for the Royals.

Though he was not eligible for the postseason in 1977, Washington was clearly a part of Kansas City’s long-term plans. And in 1978, Washington made the Royals’ Opening Day roster as a utility infielder. Patek, now 33, was named to the All-Star Game that season and handled most of the shortstop duties. Washington appeared in 69 games, mostly as a defensive replacement, hitting .264 with 12 steals.

Patek, however, played every inning of all four ALCS games in the field – hitting .077 – as the Royals fell to the Yankees for the third straight year.

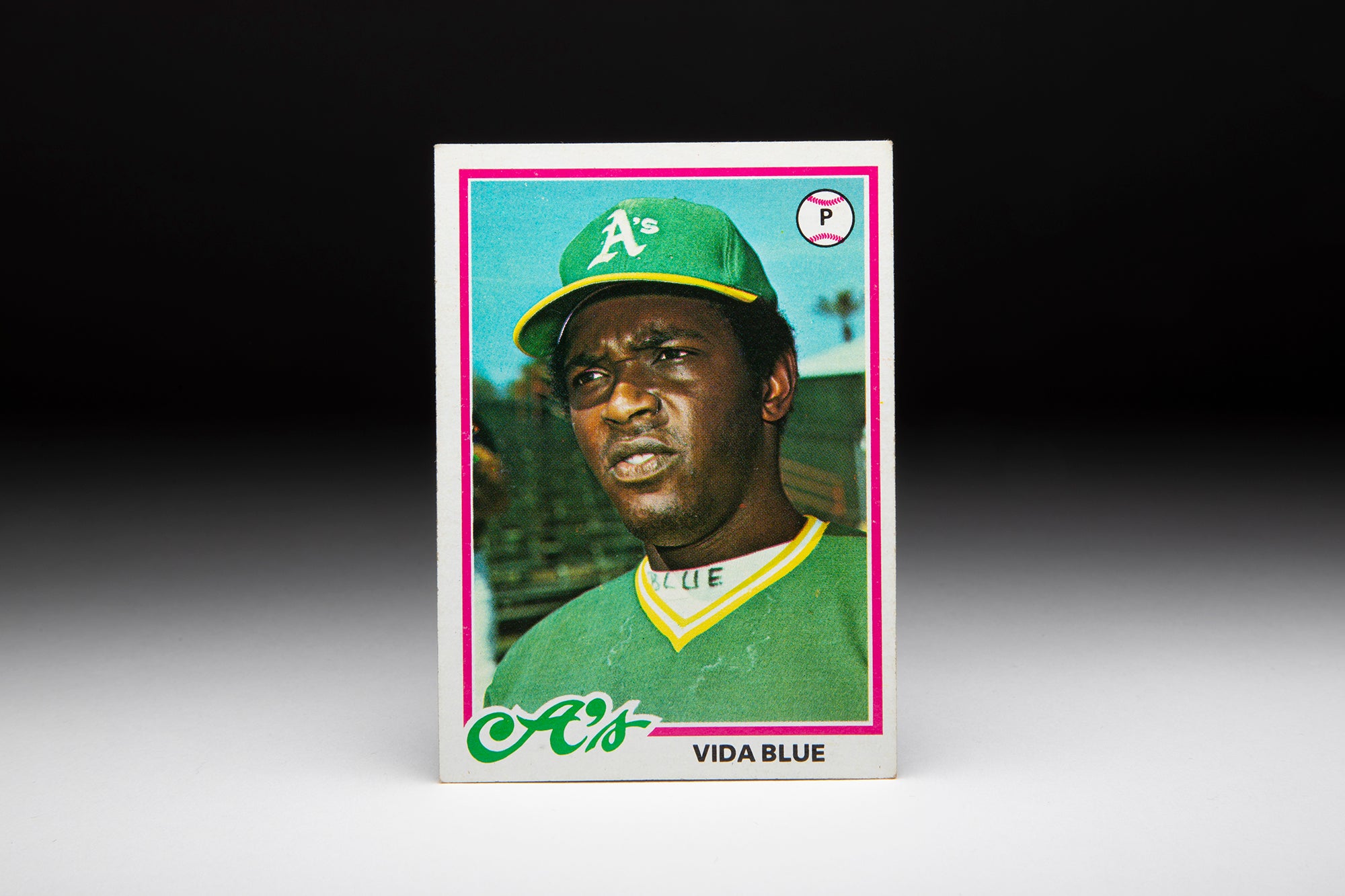

Washington played in 101 games in 1979 in large part due to a broken hand suffered by White on May 8 when he was hit by a pitch from the Rangers’ Ed Farmer. Washington saw regular duty at second base until White returned in June before supplanting Patek at shortstop in September when Patek was slowed with a shoulder injury and went into a prolonged slump. The Royals failed to repeat as AL West champions but Washington hit .254 in 101 games, connecting on the first two home runs of his career – one from each side of the plate – in a Sept. 21 game against Oakland.

“I think it was an accident,” Washington told United Press International of his power surge. “But I wouldn’t mind having a few more accidents like that.”

When Patek signed with the Angels as a free agent following the season, Washington was primed to take over the starting position and beat out Rance Mulliniks for the starting job in Spring Training.

“U L played well the last 30 days of last season and he played well in winter ball in Venezuela,” new Royals manager Jim Frey told the News-Press of Fort Myers, Fla., during Spring Training. “We’ll…let the best man win.”

Washington drew the starting assignment on Opening Day and held the job all year, hitting .273 with 79 runs scored (while batting out of the No. 9 hole much of the season), 11 triples, 53 RBI and 20 steals. The Royals recaptured the AL West title and again faced the Yankees in the ALCS. In his first postseason action, Washington hit .364 and keyed a rally in the decisive Game 3 when his two-out infield single off Goose Gossage extended the eighth inning. With the Royals trailing 2-1 with two on and two out, George Brett homered to give Kansas City a 4-2 lead. Then in the bottom of the eighth, Washington grabbed a Rick Cerone line drive with the bases loaded and no one out, doubling Reggie Jackson off second base to effectively kill the rally.

“I would change my name, too,” Washington told the Associated Press, referring to never-ending questions about what his initials stood for. “But my momma and daddy must have had something in mind when they gave me my name.”

Washington’s fielding improved in 1981 – he made just 12 errors in 98 games – but his batting average dropped to .227. But Washington was still highly coveted around the league and the Mets made a run at him in the offseason. And after missing most of the month of May in 1982 with back spasms, Washington hit .286 that year with 10 homers, 60 RBI and 23 steals. He returned to his toothpick habit that season as well.

The Royals then extended Washington with a three-year deal that ran through the 1985 season.

“I think he’s blossomed,” White said of his double play partner in the spring of 1983.

The blossoming may have been a direct result of the back injury.

“I attribute a lot of things toward the pressure I had on me,” Washington told the News-Press in the spring of 1983. “My job was in jeopardy; a lot of people thought I couldn’t play; there were trade rumors.

“It might have been a blessing that (backup shortstop) Onix (Concepción) was playing well when I returned (from the back injury). I wasn’t completely well, and that gave me an opportunity to get myself together.”

On Jan. 7, 1985, the Royals traded Washington the Expos for Mike Kinnunen and a minor leaguer. The Royals agreed to pay half of Washington’s $650,000 salary in the final season left on his contract.

Slated to be a utility player, Washington hit better than .500 in Spring Training but was unable to pry the starting shortstop job away from Hubie Brooks. He hit .249 in 68 games off the bench and then became a free agent.

On April 24, 1986, Washington signed with the Pirates and reported to Triple-A Hawaii, where he hit .242 in 36 games before being called up to Pittsburgh in June, where he assumed a similar bench role as he had with the Expos in 1985. Washington hit .200 in 72 games with the Pirates and then returned to Pittsburgh on a minor league deal for the 1987 campaign. But he failed to make the Opening Day roster and spent most of the year in Vancouver, the Pirates’ new Triple-A affiliate. Pittsburgh brought him up to the majors for 10 games in September, which would turn out to be the last 10 games of Washington’s big league career.

After some time with the Reds in Spring Training of 1988, Washington retired as a player. He took a job as manager of the Pirates’ Class A team in Welland, Ontario, in 1989 (where Tim Wakefield first began throwing the knuckleball after switching to the mound from first base), played in the Senior Professional Baseball Association that fall and later managed and coached in the minors with the Royals, Dodgers, Twins and Red Sox.

Washington finished his 11-year big league career with a .251 batting average, 358 runs scored and 132 stolen bases. And though he may have been best known for a small piece of wood protruding from his mouth, Washington’s big league legacy was far from a footnote for a player who beat the odds to become a national name.

“Hey, I wasn’t a number one pick,” Washington told the News-Press midway through his career. “I guess a lot of people feel like I’m lucky to be here…that I shouldn’t even be here.”

Washington passed away on March 3, 2024, at the age of 70.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum