- Home

- Our Stories

- Athletics of 1927 fielded a roster filled with future Hall of Famers

Athletics of 1927 fielded a roster filled with future Hall of Famers

Imagine having a successful young team filled with up-and-coming stars that was perceived to lack the veteran leadership needed to win a title. But then, under the sage leadership from a wily legend of the sport, the club acquires a trio of Cooperstown-bound players nearing the end of their careers to hopefully lead their youthful charges to a title.

Unfortunately, as the saying goes: “The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry.” In this instance, the ball club that fits this unique criteria is the 1927 Philadelphia Athletics.

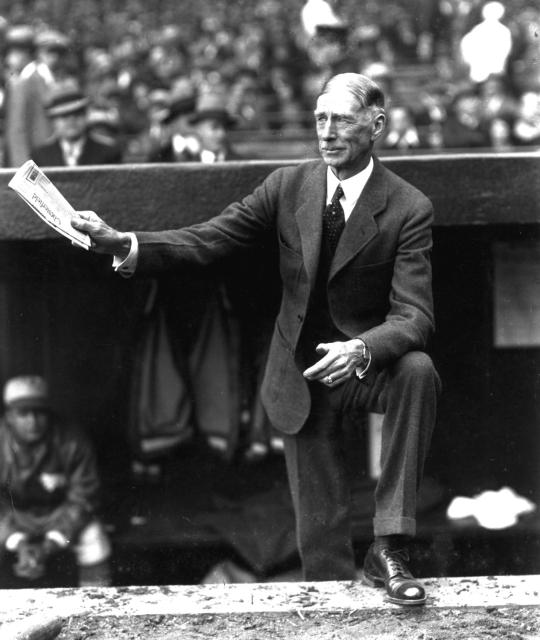

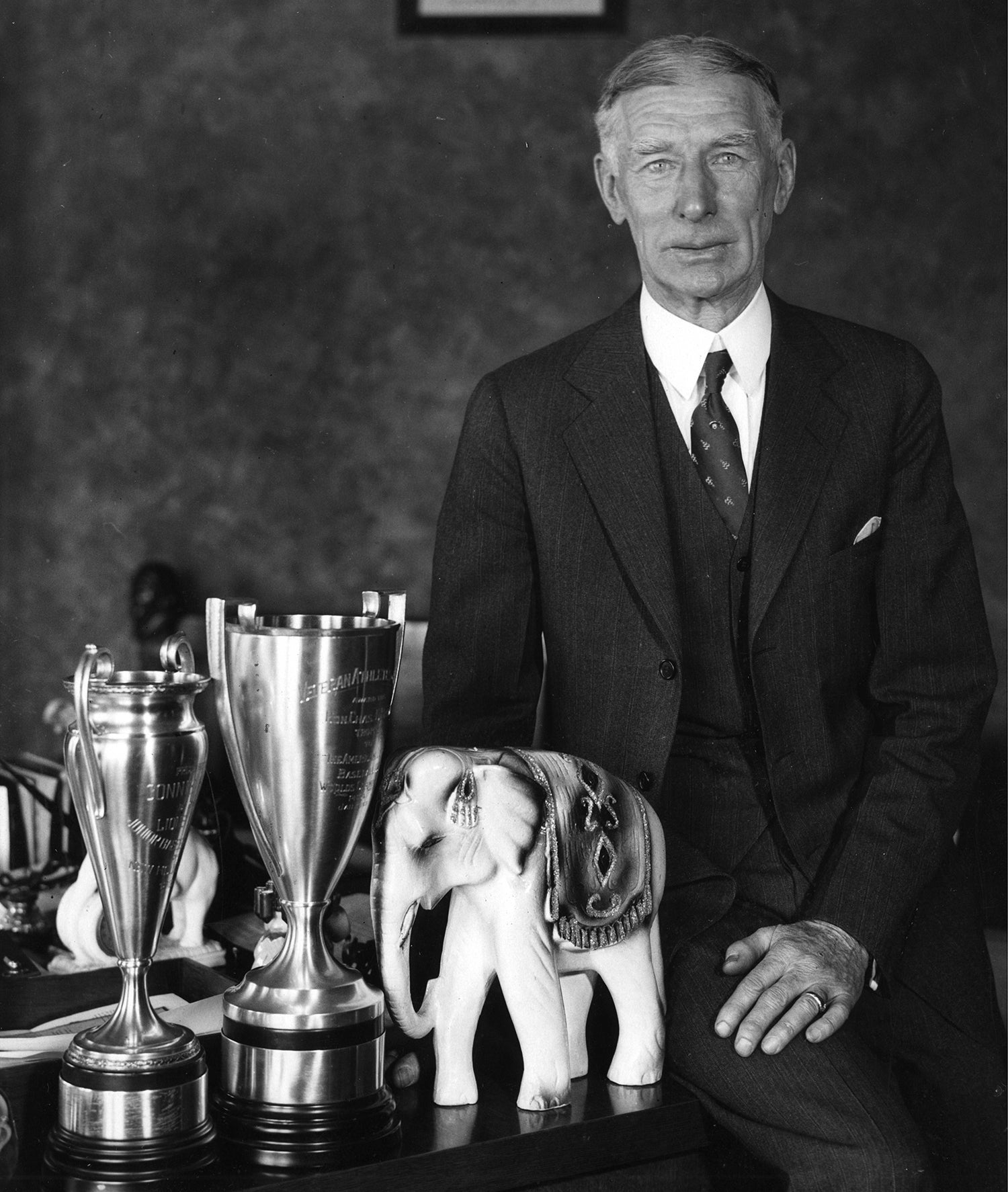

Ninety-five years ago, the A’s were being led by the venerable manager and co-owner Connie Mack, a 64-year-old former catcher who had guided the White Elephants since the American League began play in 1901.

After a 1926 campaign ended in disappointment, as the Athletics finished in third place in the eight-team Junior Circuit with an 83-67 record, the Tall Tactician knew drastic changes needed to be made if the A’s were to overtake the soon-to-be named Murderers’ Row New York Yankees of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri and Earle Combs, all future Hall of Famers.

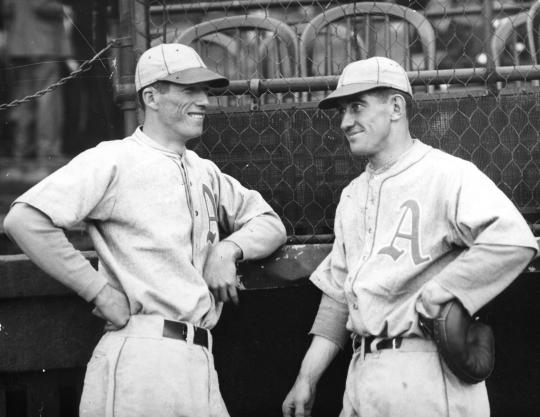

Heading into the 1927 season, the Athletics had their share of young and future bronze-plaque talent, including catcher Mickey Cochrane (24), outfielder Al Simmons (25), first baseman Jimmie Foxx (19) and pitcher Lefty Grove (27).

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In the offseason after the 1926 campaign, Mack supplemented his squad with such legendary names as Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins and Zack Wheat, all released by their previous club that winter.

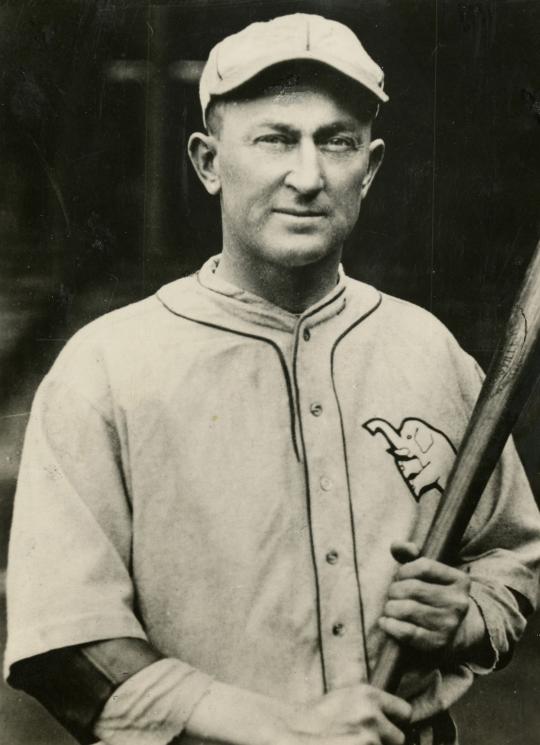

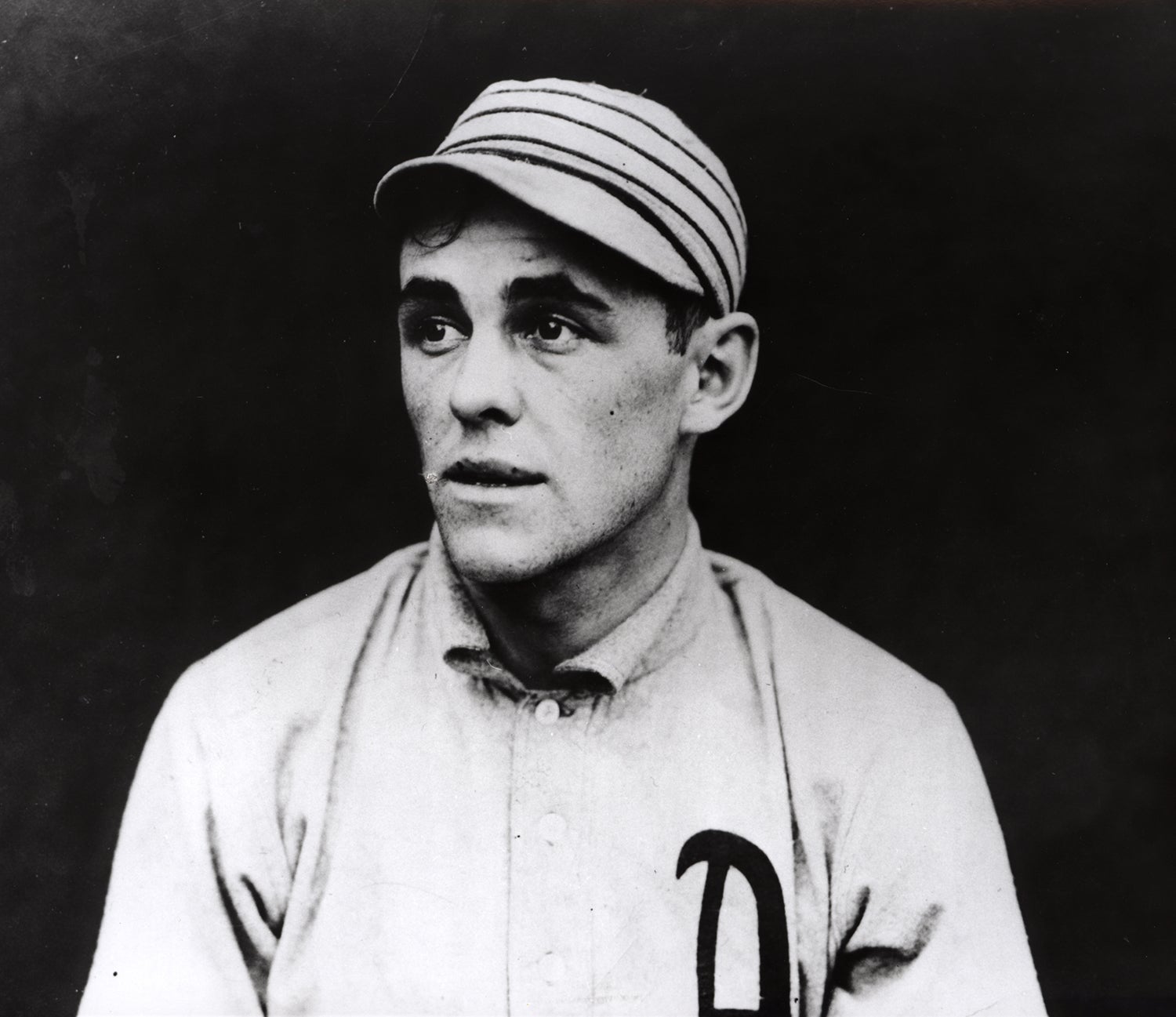

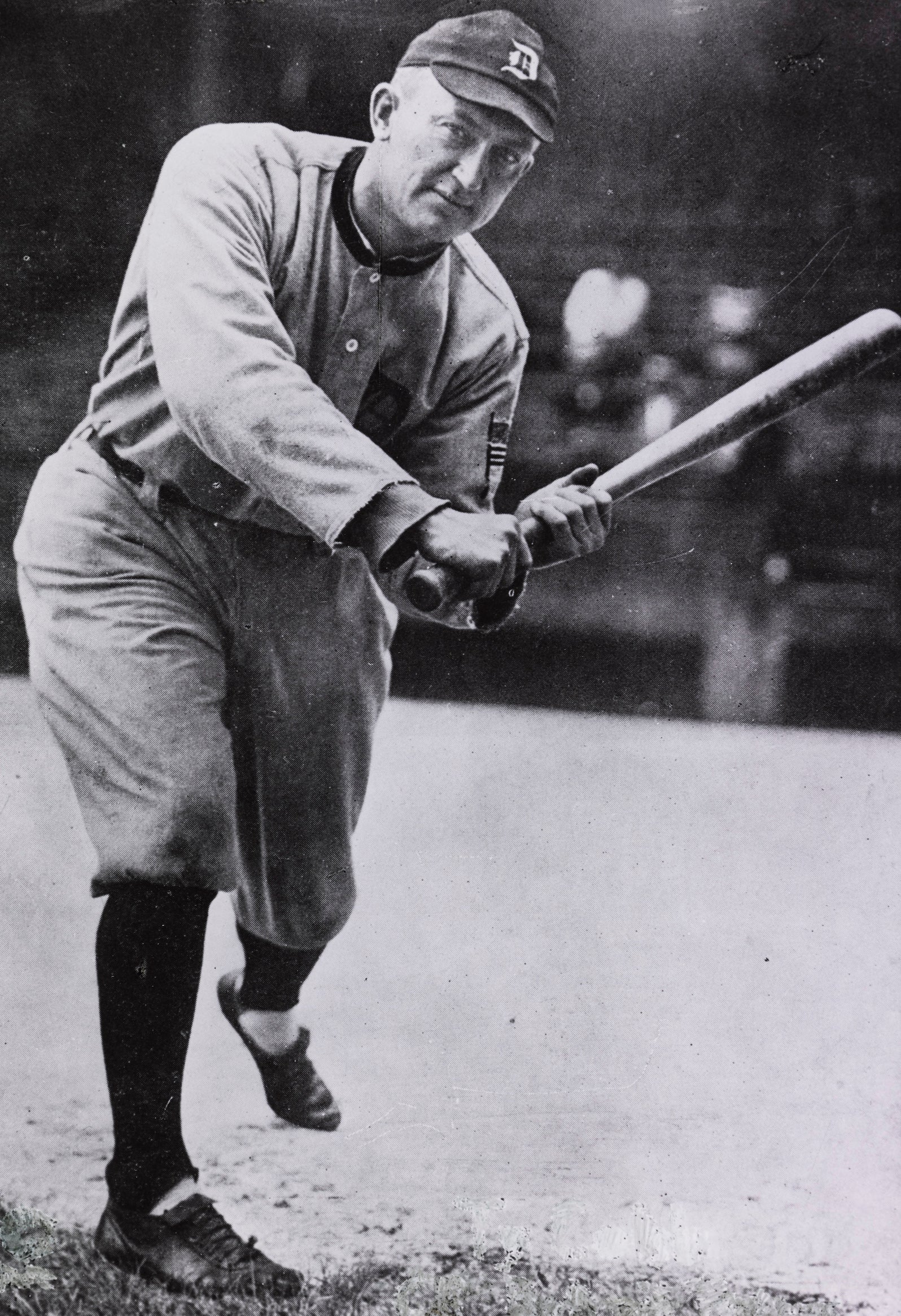

Cobb, generally considered at the time the game’s greatest-ever player, had spent his entire 22-season career with the Detroit Tigers before signing with the A’s. With a .368 career batting average, 12 batting titles and six seasons serving as a player/manager, he would now be playing at age 40 with a new team. The Georgia Peach was part of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural election Class of 1936.

“I think this is the proper spot for me,” Cobb told reporters in February 1927, “and I am glad to be with the Athletics. They have a mighty fine chance for the pennant. I only hope that I will be spared any illness or accidents for I am just rarin’ to show the public that I can still reach dizzy heights in baseball.

"Because of certain incidents that received prominence during the offseason, I call this my vindication year and I’m out to play the kind of baseball that will make folks write letters to their cousins in the country.”

The “certain incidents” Cobb refers to involved a gambling scandal in which former pitcher Dutch Leonard accused Cobb and Tris Speaker in joining with him in betting on a supposed fixed game during the infamous 1919 “Black Sox” World Series.

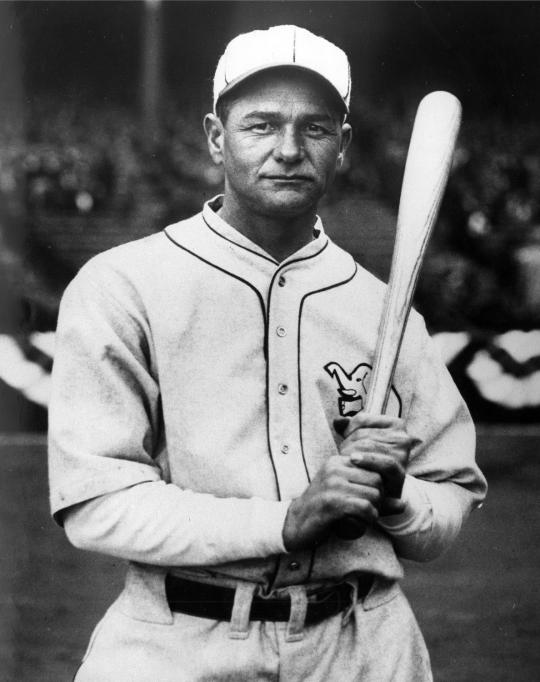

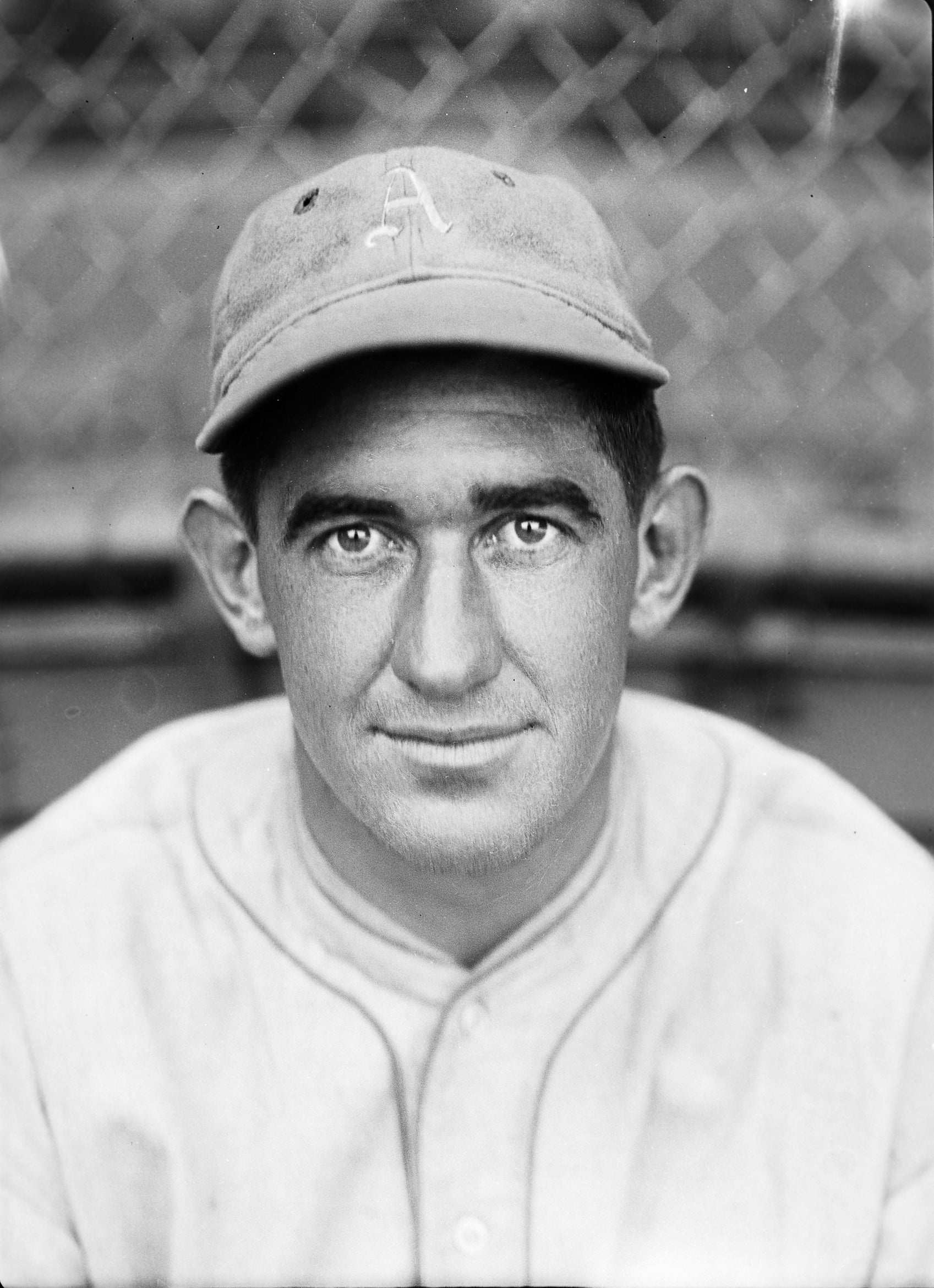

Collins, who spent his first nine big league seasons with the Athletics until Mack dismantled the team following an AL pennant in 1914, then burnished his reputation as an all-around star second baseman during a dozen years with the Chicago White Sox. Turning 40 during the 1927 season, Collins, a member of the Hall of Fame Class of 1939, had been Chicago’s player/manager for two seasons prior to rejoining the A’s with 3,228 hits, 735 stolen bases and a .333 career batting average.

“When I look around the country,” said Collins after signing a free agent deal with the Athletics in December 1926, “and see the infield talent I am convinced that I have at least one year of baseball in me. I am going to play second base for the Athletics next season and if it is going to be my last in the big leagues you may rest assured it will not be my worst. If I am going to step out, and I will not stay a minute longer than I think I can keep up with the pace, I will prove to some persons that I still can play.

“I’d like to make 1927 the banner year of my baseball career. I certainly could not seek a more suitable place to play than around the spot where I broke into baseball and for the man whom I regard as the greatest in the national game.”

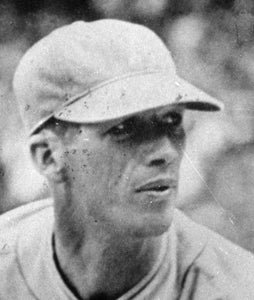

While Cobb and Collins were making noise in the AL, Wheat was making a name for himself in the Senior Circuit with the Brooklyn team for 18 years before signing with the A’s. A lefty-swinging outfielder, he hit at least .300 a dozen times and led the NL in batting in 1918 with a .335 mark.

A defensive whiz with a strong throwing arm, the Hall of Fame Class of 1959 member turned 39 during the 1927 season.

“Wheat,” said Connie Mack in January 1927, “will add to our outfield punch. You can imagine the moundsman who faces the Athletics in 1927 with Wheat, (Sammy) Hale, Collins and Simmons as the master sluggers. You can bet our pitchers will be glad to see Collins and Wheat adding to their well-known batting power to the attack. Prospects look bright for us, and I think that Wheat will be a terror to the American League pitchers.”

John Kieran, a sports columnist with The New York Times, was circumspect in his February 1927 assessment of Mack’s offseason maneuvering.

“Connie Mack seems to think his White Elephants will lead the American League pennant parade of 1927,” Kieran wrote. “In recent years, the Elephants were generally backing up instead of forging ahead in the dash for the tape.

“Collins had an old leg injury that forced him out during the summer. Cobb didn’t even try to play as a Detroit regular last year. Wheat was a regular with the Robins, but that doesn’t necessarily entitle a player to a high rating as a regular on a prospective championship club.”

In 1926, the newly signed trio all put up productive offensive numbers, but “The legs are the first to go,” a longtime athletic saying, was certainly evident for the aged baseball heroes. All three were slowing down. Cobb batted .339 with 62 RBI in 233 at bats, Collins’ batting average was .344 in 375 at bats with 13 stolen bases and 66 runs scored, and Wheat hit .290 in 411 at bats with 68 runs.

It was said at the time that Mack, who hadn’t had a pennant winner since 1914, was throwing all his resources in an attempt to recapture that past glory. With 1927 being Mack’s 43rd consecutive year in the game, the lean leader had won six pennants and three World Series crowns.

The financial cost to Mack for hiring the three grand men of the game to buttress a team of younger players is not known, but estimates at the time pegged the total at nearly $100,000, with Cobb receiving the lion’s share.

“I think we have the reserve strength with two men for each place,” said Mack during Spring Training in Fort Myers, Fla. “I do not think we will be caught napping in the stretch if we are fortunate enough to be ‘up there’ when the real test comes.

“In the past we have gone ‘great guns’ but cracked in the pinch. Since the close of last season we had added players who have experience enough to guarantee them against cracking. And Ty Cobb, Zack Wheat and Eddie Collins will add the punch to the club.”

Preseason prognosticators favored the Athletics in the AL race, with The Associated Press conducting a poll of baseball writers around the circuit and 29 out of those 43 picking the Mackmen to place first.

After a season-opening series against the A’s, in which the Yankees won three of four, Ruth said: “My club would be foolish to laugh off the A’s when they have so much power and brains on their roster…For the Macks will be harder to beat when the warm weather oils up their arms and legs.”

By midseason, a vulnerability in the A’s was exposed and foreshadowed a season that was suddenly in doubt.

By the end of June, the Athletics had a 37-32 record, were in fourth place, and had fallen 12 games behind the Yankees atop the league standings.

Washington Senators player/manager Bucky Harris said after a five-game series with the A’s in mid-June: “Cobb and Collins don’t need any alibis, after the careers they have had, but it will be a big surprise to me if they last the better part of the season. They still have their batting eyes, but their legs have gone back beyond repair. They aren’t the same in the field and hits will get past them that they used to cut off. Their benefit to the Athletics has been ballyhooed a little too much.”

Philadelphia’s midseason struggles were disappointing but not insurmountable, according to Mack.

“Cobb, Collins and Wheat have done everything I expected of them,” Mack told columnist Billy Evans, the longtime umpire and future Hall of Famer. “And that goes in spite of the fact that injuries have handicapped all three.

“I didn’t expect any of them to be able to go the entire route of 154 games, for I knew their legs wouldn’t stand the strain. I looked for them to go big in the spring, sag a bit during the middle of the season, and then come strong at the finish. They did their bit early, but our inconsistent pitching minimized any added strength the trip supplied.”

On Sept. 21, the A’s were 86-59 and sat in second place but had fallen 17 games behind the Yankees. It was also on that date that Cobb played his last game of the season. He left the team to go on a hunting trip, despite the fact that the A’s season would not conclude until Oct. 2.

“I’ve enjoyed my association with the Athletics, and I’ve done my level best this season,” Cobb said. “They don’t need me now and I will be on my way for a hunting trip in Wyoming and the Northwest late this afternoon.

“This is my 23rd season in baseball and I’m getting a little tired of the game. Connie Mack invited me back next year and told me he was anxious I should return. I really don’t know right now what I intend to do. I will make up my mind during the winter.

“This year was largely a campaign for vindication and an attempt to win back my self-esteem in baseball circles. Sometimes I feel there are lots of young men coming up who could replace me and I really would not be missed.”

The Athletics – sans Cobb – played out the string and finished with a 91-63-1 record, a successful campaign most years but not close to first place as they trailed the pennant-winning Yankees by 19 games.

The trio of rare old antiques the A’s had acquired to get them over the hump put up more than respectable numbers, but age had caught up to them.

In 1927, Cobb hit .357 with a .440 on-base percentage and 104 runs scored in 490 at bats; Collins hit .336 with 50 runs scored in 226 at bats, and Wheat hit .324 with a .379 OBP in 226 at bats. Cobb played again for the A’s the next season before retiring, Collins hung around as a part-time player but mostly assisted Mack over the next three seasons, while 1927 proved to be Wheat’s final season.

In a piece written at the end of the year, syndicated sports columnist Joe Villa dissected what went wrong for an Athletics team that entered 1927 with such high expectations.

“The 1927 season was a bitter disappointment to Mack,” Villa wrote. “He had molded what he thought was a championship team, with Ty Cobb, Al Simmons and Zack Wheat in the outfield, Eddie Collins at second base and a pitching corps that, if it was not very impressive to outsiders, at least appealed to him.

“But Cobb was almost useless in the outfield, an injury put Simmons on the shelf for weeks, Wheat was effective only in spots, Collins bogged down under the strain of playing regularly and the pitching staff was a bloomer. The Athletics never had a real chance to beat out the Yankees, who had improved at least 30 percent since 1926.”

The Yankees not only swept the Pirates in the 1927 World Series, but also swept the Cardinals the next year. Mack, who would retire after the 1950 season, led the A’s to three consecutive pennants from 1929-31, winning his final two World Series in 1929 and 1930.

But if the contest was based on fielding a roster with future Hall of Fame talent, the Athletics of 1927 would be hard to beat.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum