- Home

- Our Stories

- Clemente’s October led Pirates to 1971 title

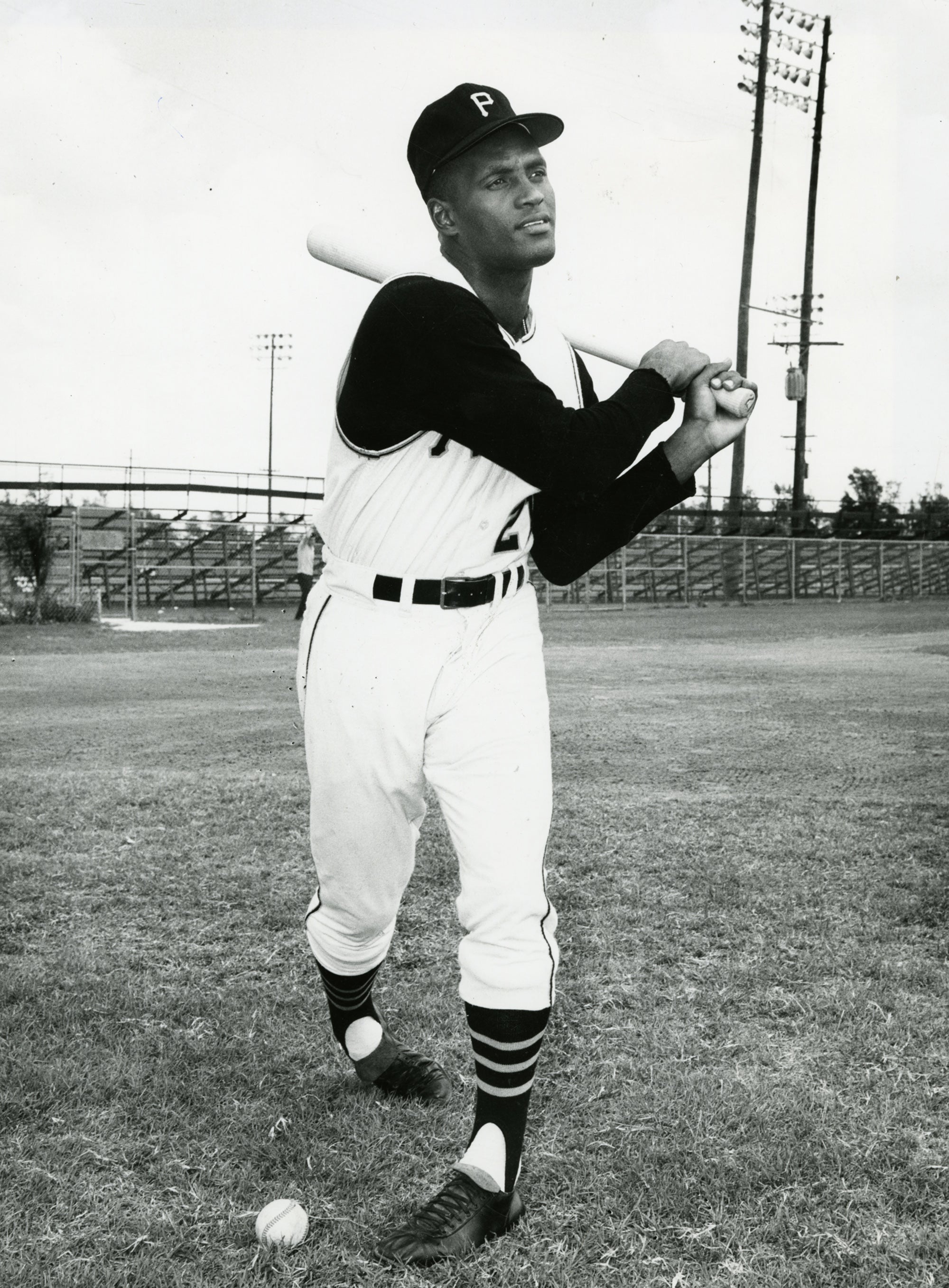

Clemente’s October led Pirates to 1971 title

In a literal sense, it is not possible for one player to carry a team to victory, even in a short series. After all, baseball is a team game, one in which each club comes to rely on a regular lineup of nine players, or a total of 10 when the designated hitter comes into play.

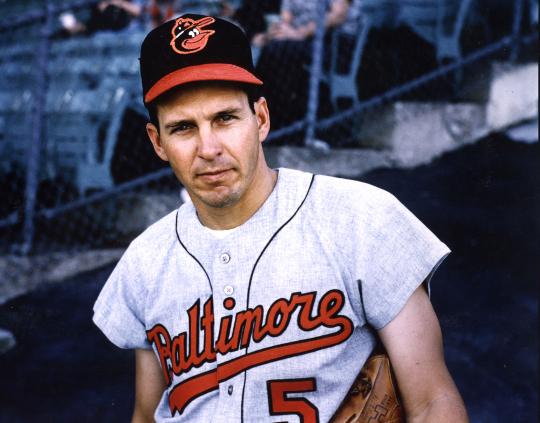

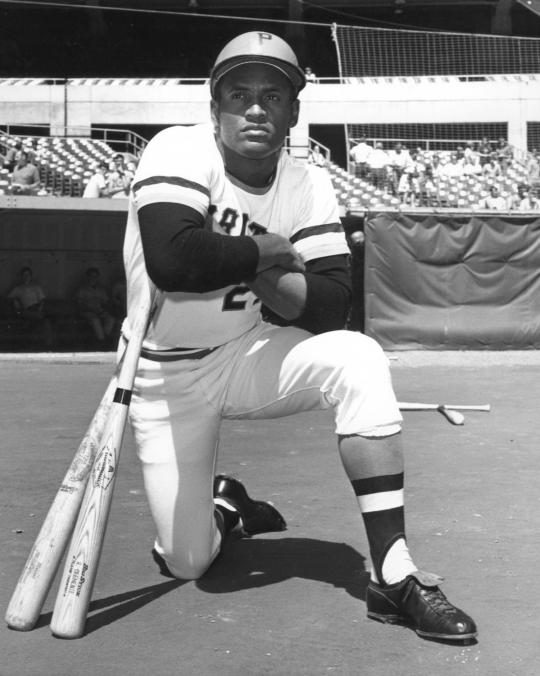

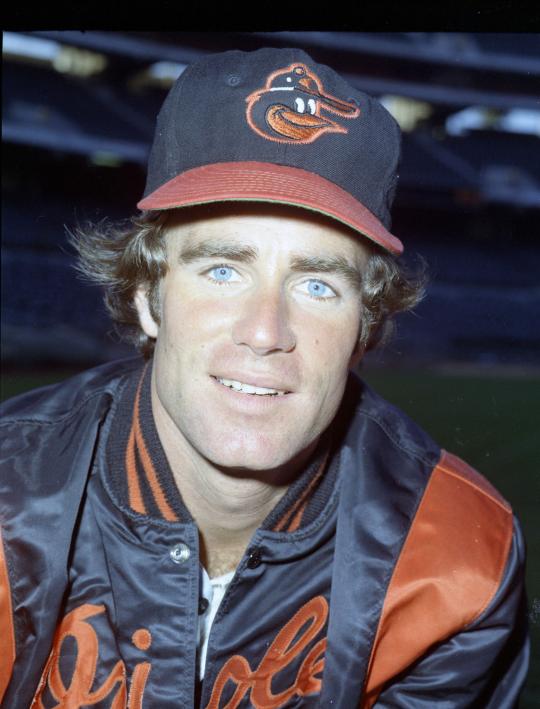

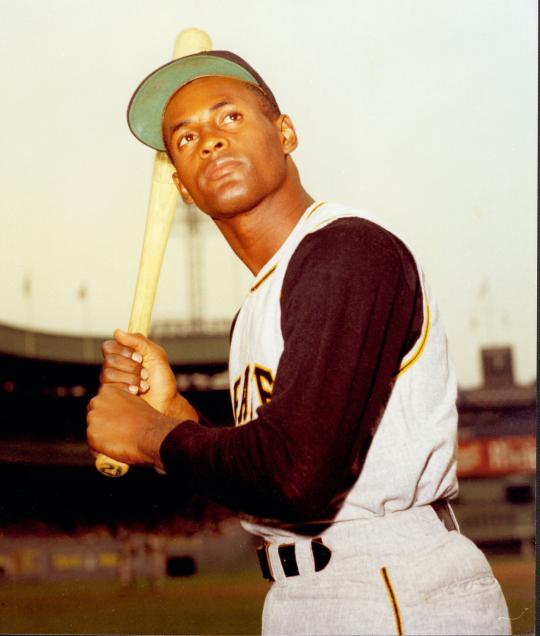

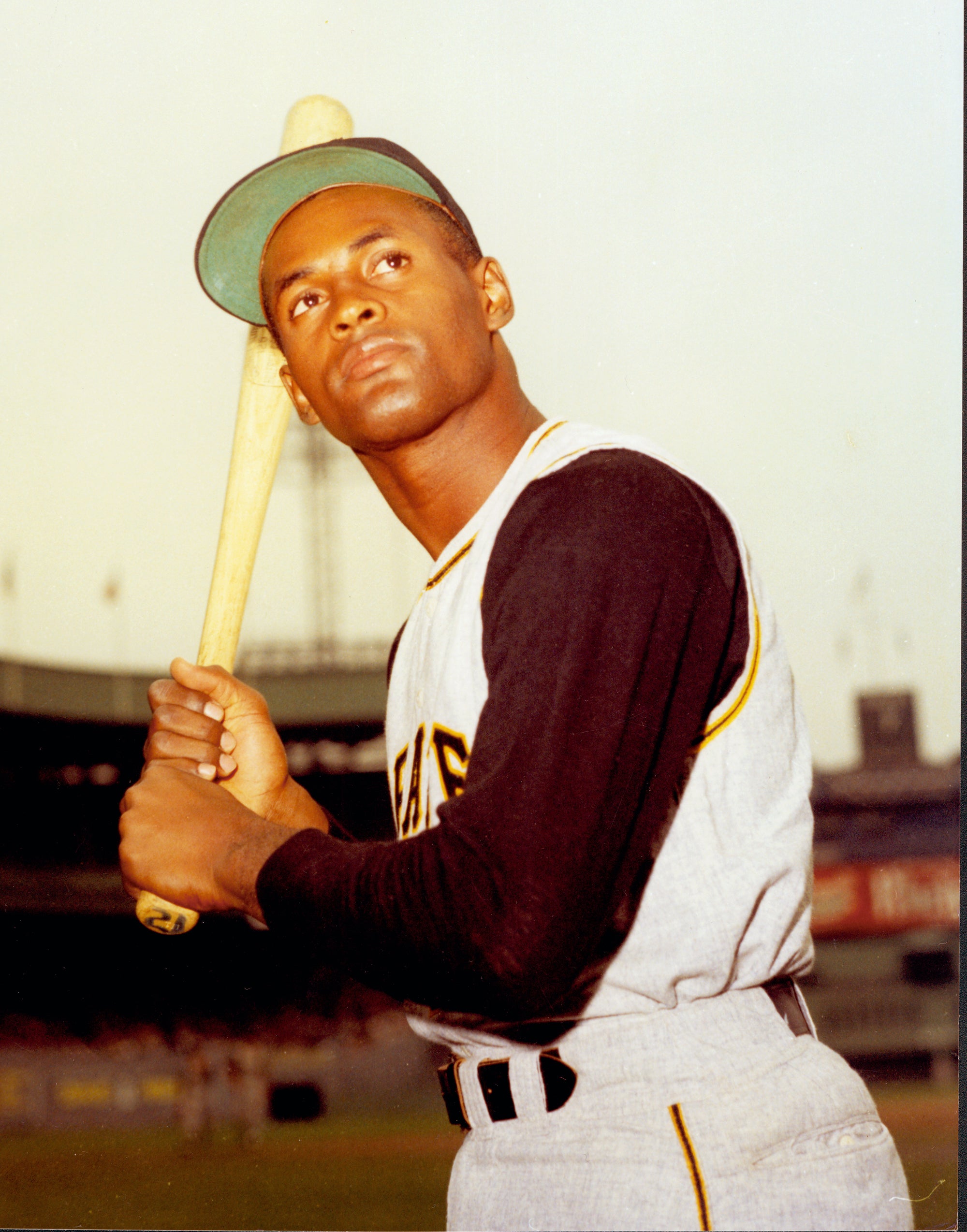

Yet, in October of 1971, Roberto Clemente came as close to carrying his team to a world championship as any one player has ever done. In a World Series matchup that heavily favored the powerhouse Baltimore Orioles, Clemente lifted the underdog Pittsburgh Pirates to one of the most remarkable upsets in Fall Classic history. Hitting the ball with a relentless ferocity, running the bases like a man 10 years younger than his listed age of 37, and fielding his position with breathtaking flawlessness, Clemente galvanized the Pirates, almost willing them to a World Series title that most had considered unlikely, if not impossible.

The events of the first two games of the ’71 World Series did not bode well for the Pirates. They were overmatched by the Orioles, who won the two games by the combined score of 16-6. The victories by the Orioles fulfilled most of the pre-Series expectations. Most writers had predicted the Orioles would win the Series with ease, and quite possibly in a four-game sweep.

Pirates Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Clemente was one of the lone bright spots for the Pirates. He collected four hits in nine at-bats and had also played well in the field.

His stellar defensive effort was highlighted by a Game 2 play in which he made a running catch along the right field line, then immediately spun and unleashed a laser-like throw to third base, where he nearly retired Baltimore’s speedy baserunner Merv Rettenmund.

For most right fielders, they would have had no chance of preventing Rettenmund from advancing to third, but Clemente made it perilously close, much to the shock of Rettenmund himself.

As well as Clemente played in the first two games, he was in no mood to discuss the merits of his performance. He was more concerned with the poor condition of Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. A rainy late summer in Baltimore, coupled with a series of NFL games, had left the playing surface in muddled condition for the World Series. Clemente also criticized the sight lines at Memorial Stadium. “This is not a big league ballpark.” Clemente told the Sporting News. “You cannot see the ball in the outfield. You can’t see where it’s going when they hit it in the air… You have to worry about the holes [in the ground] and the grass.”

The condition of the field left Clemente furious. But he was also upset by the Pirates’ on-field performance. He became further angered when he started to hear members of the media predicting an embarrassing four-game sweep at the hands of the Orioles.

The World Series now moved to Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium for Game 3. Over the first six innings, the Pirates played competitively, taking a 2-1 lead. But with the game very much in the balance, Clemente helped set the stage for a crucial rally.

Leading off the bottom of the seventh inning, Clemente tried to check his swing on a pitch from Baltimore’s Mike Cuellar, but hit a weak tapper toward the mound. Instead of conceding the out, Clemente ran hard from the outset – as he always did. In front of the mound, Cuellar fielded the easy comebacker, but his body was slightly off balance. Noticing Clemente’s all-out sprint toward first base, Cuellar felt pressure to hurry his throw to first baseman Boog Powell.

Cuellar’s hasty reaction resulted in an errant toss, which pulled Powell off the bag. Clemente was safe, a routine pitcher-to-first-putout instead becoming an error against Cuellar.

Perhaps rattled by his own mistake, Cuellar walked Willie Stargell, putting Pirate runners at first and second with no one out. Cuellar then ran the count to 1-1 against Bob Robertson. Noticing that Brooks Robinson was playing deep at third, Danny Murtaugh signaled to Frank Oceak, his third base coach, that he wanted the slugging Robertson to bunt.

A surprised Clemente, who was leading off second, waved his arms frantically in an attempt to call time and confirm that Oceak had indeed signaled for the sacrifice. But second base umpire Jim Odom failed to grant Clemente the time-out, as Cuellar delivered one of his patented screwballs to the plate.

Robertson completely missed the sign from Oceak. Instead of squaring into bunting position, Robertson unleashed a full uppercut swing and drove the ball deep toward the opposite field. A few seconds later, the ball landed in a section of stands over the 385-foot sign at Three Rivers Stadium. The Pirates, now equipped with a 5-1 lead, would coast to victory in Game 3. It was a must-win for the Pirates and one that changed momentum.

Clemente continued to play well in the Series. In Game 4, the first night game in Series history, he went 3-for-4, as the Pirates stormed back from an early three-run deficit to win, 4-3. The next day, Clemente drove in a run in a 4-0 shutout.

And even in a tough, extra-inning loss in the sixth game, Clemente pounded out a triple and a home run against the great Jim Palmer.

It was now on to Game 7, which turned into a classic pitcher’s duel between Pirates ace Steve Blass and the lefty-throwing Cuellar, one of four 20-game winners for the Orioles that season. The game remained scoreless heading to the fourth inning. Cuellar then breezed through the first two Pirate batters.

Having retired 11 consecutive Pirates to start the game, Cuellar now faced Clemente. Hoping to throw Clemente off balance, Cuellar threw him a curve ball over the outside part of the plate. Cuellar’s attempted pitch location was consistent with the Orioles’ scouting report against Clemente: throw him breaking pitches away, but keep the ball down, as Baltimore superscout Jim Russo had warned.

Although he kept the ball away from Clemente, he allowed the curve ball to hang high, rather than keep it below the belt. Unleashing a powerful swing, Clemente cracked a drive into left-center field. The ball sailed into the Memorial Stadium bleachers, just to the right of the 390-foot sign.

Clemente’s home run gave the Pirates a 1-0 lead. It would prove crucial, as the Pirates protected a 2-1 lead heading to the bottom of the ninth. Blass, still on the mound, retired the first two Orioles batters.

He then faced Merv Rettenmund, who bounced a high hopper over the second base bag. Pirates shortstop Jackie Hernández fielded the tricky ground ball and fired to first base, ending the game and giving the Pirates their first world championship since 1960.

While Blass had pitched brilliantly in his two Series starts, it was Clemente who was clearly the MVP of the World Series. For more than an hour after the game, Clemente remained trapped on the NBC-TV platform, unable to move because of the mass of players, reporters and officials that had convened in the Pirates’ clubhouse.

When Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince started the post-game show by asking Clemente a question, Roberto began his response by acknowledging his parents and asking for their blessing – in his native Spanish. It was the kind of moment never before witnessed by an English-speaking sports audience.

Clemente’s Series’ accomplishments included hits in all seven games, a .414 batting average, two home runs, four RBI, aggressive and intelligent baserunning, and spectacular throws from right field. “Clemente was just all-world,” said Dave Johnson, the Orioles’ second baseman who would later become a world championship manager.

For many years, Clemente had been respected by insiders as one of the game’s great players, but the Pirates’ status as a small-market franchise had caused him to be overlooked by fans and media nationwide. All of that had now changed. Clemente’s all-around performance on national television transformed the public’s perception of him as a very good player into awareness of his true status: That of a superstar.

“He turned 10-year major league veterans into 10-year-old fans,” Blass, a teammate of Clemente for nine seasons, said during a visit to Cooperstown in the late 1990s. “And that’s what’s special about the very special ballplayers. You just really enjoy watching them play. You even enjoy watching them run out to their position. You just can’t get enough of the special guys. Clemente was just that good.”

Indeed he was.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum