- Home

- Our Stories

- Pioneering Cleveland broadcaster Jack Graney named 2022 Frick Award winner

Pioneering Cleveland broadcaster Jack Graney named 2022 Frick Award winner

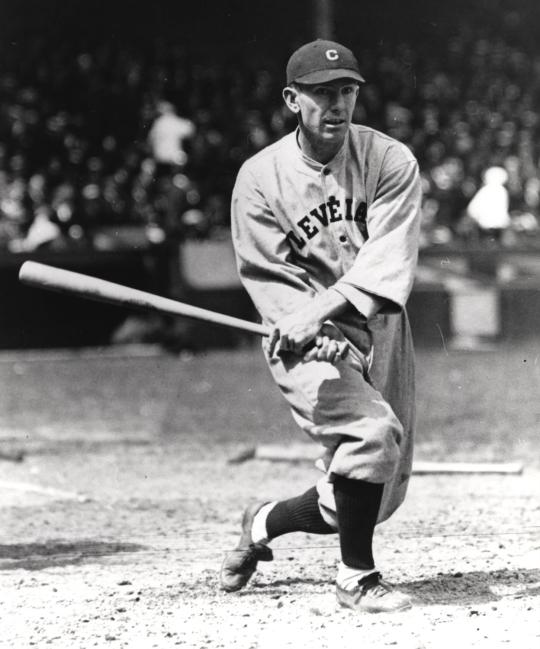

Jack Graney, a beloved Cleveland broadcaster for more than four decades, took the unique at the time career path of being a star player before shining in the booth. He has now been recognized with the highest honor the baseball broadcasting profession bestows.

On Dec. 8, Graney was selected as the 2022 recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award, presented annually for excellence in broadcasting by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. He’ll be posthumously honored this summer in Cooperstown during the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation as part of Hall of Fame Weekend, July 22-25, 2022.

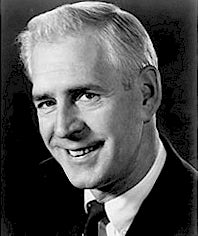

According to the late Jack Buck, the 1987 Frick Award winner who grew up in suburban Cleveland: “Mr. Graney brought to his job knowledge and controlled enthusiasm. He had a distinctive voice, high-pitched and raspy, but quite clear. You always knew, listening to him, that he knew what was going on and he told it to you simply and accurately.

“I didn't want to be a policeman or fireman. Jack made me want to make a living calling ball.”

The Frick Award is presented annually to a broadcaster for “major contributions to baseball.” The award, named after the late broadcaster, National League President, Commissioner, and Hall of Famer, has been presented annually since 1978.

Graney becomes the 46th winner of the Frick Award, as he earned the highest point total in a vote conducted by the Hall of Fame’s 16-member Frick Award Committee. The final ballot featured broadcasters whose main contributions were realized as broadcasting pioneers, identified as the Broadcasting Beginnings ballot.

During a 14-year big league playing career (1908, 1910-22) spent entirely with Cleveland’s American League team, Graney was a top leadoff hitter during the Dead Ball era, topping the AL in doubles in 1916, and in walks in 1917 and 1919.

The left fielder, though a stocky 5-foot-9 and weighing 180 pounds, covered a lot of ground and had a good arm.

After his playing career, Graney managed in the minors before getting into the automobile sales business. After the Great Depression ended his career with cars, Graney was offered the opportunity to broadcast Indians baseball games over radio station WHK in 1932, becoming what is now widely considered to be the first former big league player to broadcast a big league game.

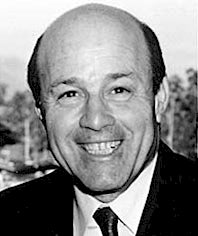

Curt Smith, baseball broadcasting historian and a member of the Frick Award electorate, said, “Graney had a rough voice in a velvet craft. He did not attend Broadcasting 101 and he was better for it. I've talked to people who said that you could walk down any Cleveland street at the time and you would hear Jack Graney from one radio after another. There was a vibrancy to his play-by-play. There was something about him that fixated listeners.

“He broke all sorts of glass ceilings in terms of what was considered appropriate in the broadcast booth. When we think of characters of the booth, we think of Dizzy Dean, Joe Garagiola and Bob Uecker. But without Graney maybe we never think of them at all, because he really turned the tide. Up until him it was more or less thought that you had to be a trained professional to broadcast. But he demolished that stereotype.”

Graney, with his famed staccato delivery, would remain the play-by-play voice of the Cleveland Indians for 21 seasons.

The only season he missed from 1932-53 was in 1945, when no Cleveland games were broadcast because of network commitments.

During the late Depression and World War II years, Graney and broadcast partner Pinky Hunter became adept at recreating games when the Indians did not send the announcers on the road with the team. Announcing via Western Union reports, the pair added their own touches to make it sound as though they were actually watching the game, even adding the roar of the crowd by using a record. “We were corny, but it was fun,” Graney recalled years later.

Graney was so popular with Cleveland fans they gave him a “night” on Sept. 4, 1953, a few weeks before he retired at the end of that season. The major gift was a bank book with a deposit of $10,000 from fans, associates, baseball writers and other well-wishers, while the players presented Graney with a solid gold wristwatch inscribed, “In deep appreciation.”

“I’ve dreaded the day when it would be time for me to retire,” said the subject to the Cleveland Stadium crowd. “You people have softened it for me. After 13 years with the Indians my legs gave out and I hung up my spikes. Now after 21 years of broadcasting, I’m hanging up my voice.”

Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller, speaking for the Indians players, told the fans: “Often, when we weren’t doing too well, Jack made us sound good.”

Cleveland Mayor Thomas A. Burke added, “Jack Graney has meant as much to baseball here as any man in the history of Cleveland.”

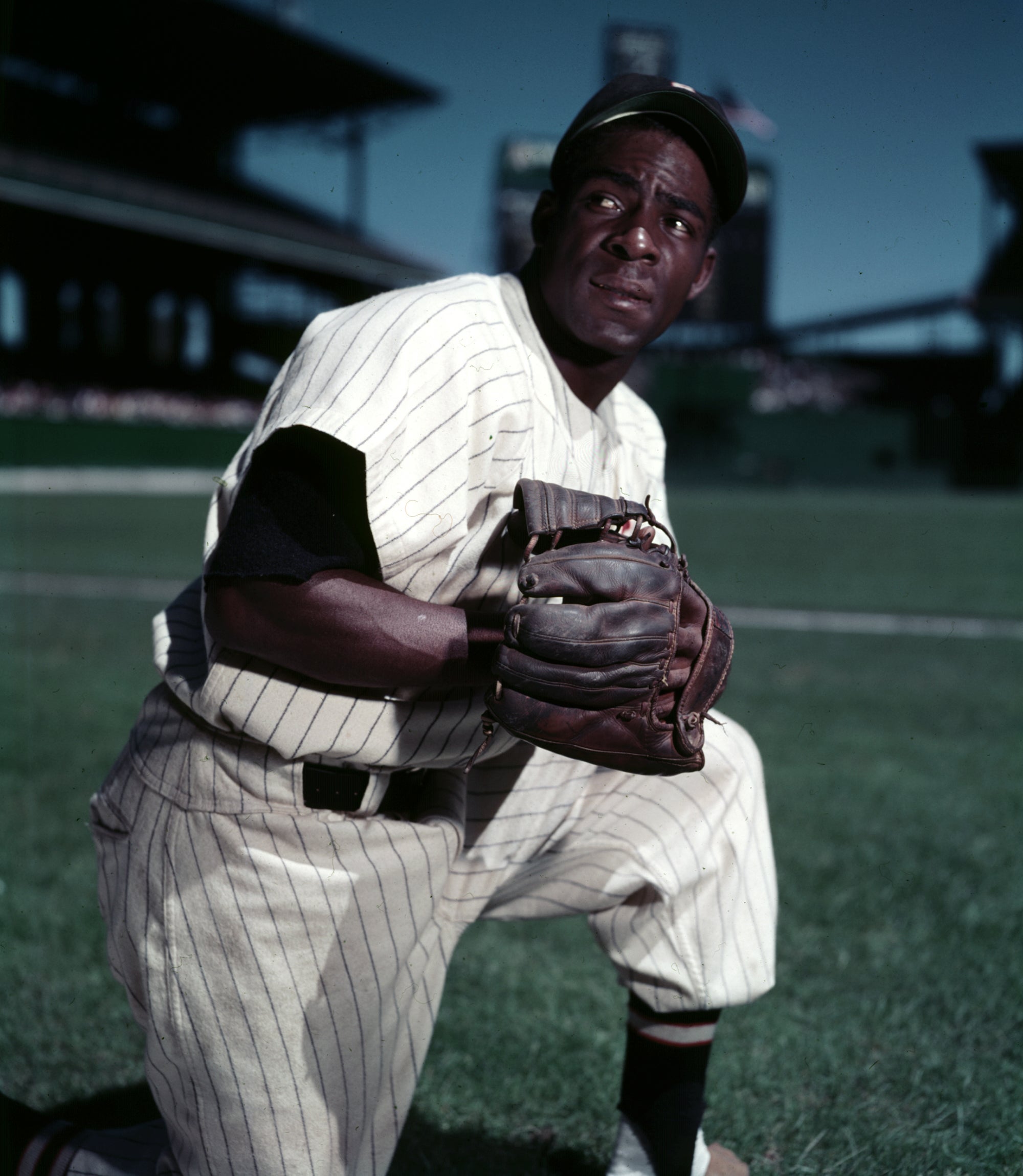

Near the end of Graney’s booth tenure, sports columnist Marty Richardson of the Cleveland Call and Post – a famed Black newspaper – praised the broadcaster’s decency and humanity towards all players.

“Over and above everything else, however, Jack has always been fair almost to a fault. And for that I don’t just like the guy. I ADORE him,” Richardson wrote. “(Larry) Doby, Satchel Paige, (Luke) Easter, (Harry) Simpson, (Dave) Hoskins, all of the colored players on the team have always gotten more than a fair shake from Jack, as have (Bobby) Avila, (Hank) Greenberg, (Al) López, (Minnie) Miñoso and the rest. Negro, Mexican, Cuban, Jew, Irishman, everybody has come in for equal, and terrifically fair, treatment from Jack.”

The Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal attempted in an editorial to explain why Graney had won a place in the hearts of listeners within the Cleveland area.

“Nobody ever used the term ‘golden-voiced’ in describing Jack Graney. ‘Sandpaper-voiced’ would be more apt,” the newspaper penned in the Sept. 29, 1953 edition. “But it is safe to say that radio listeners numbering in the millions were sorry when they heard Jack sign off Sunday afternoon following the Cleveland Indians’ final game of the season.

“Graney was popular for several reasons. As a former major leaguer himself, he spoke with authority when talking baseball. He had a rare talent for making the game sound exciting. And he rarely if ever said an unkind word about anyone. He made no secret of his partisanship – you could tell from the tone of his voice whether the ball which had just been sent going, going, GONE! had been clouted by an Indian or a member of the opposing team. But he was always fair, for all that – a fine example of sportsmanship.”

Graney died April 20, 1978, at the age of 91.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum