- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Earl Williams

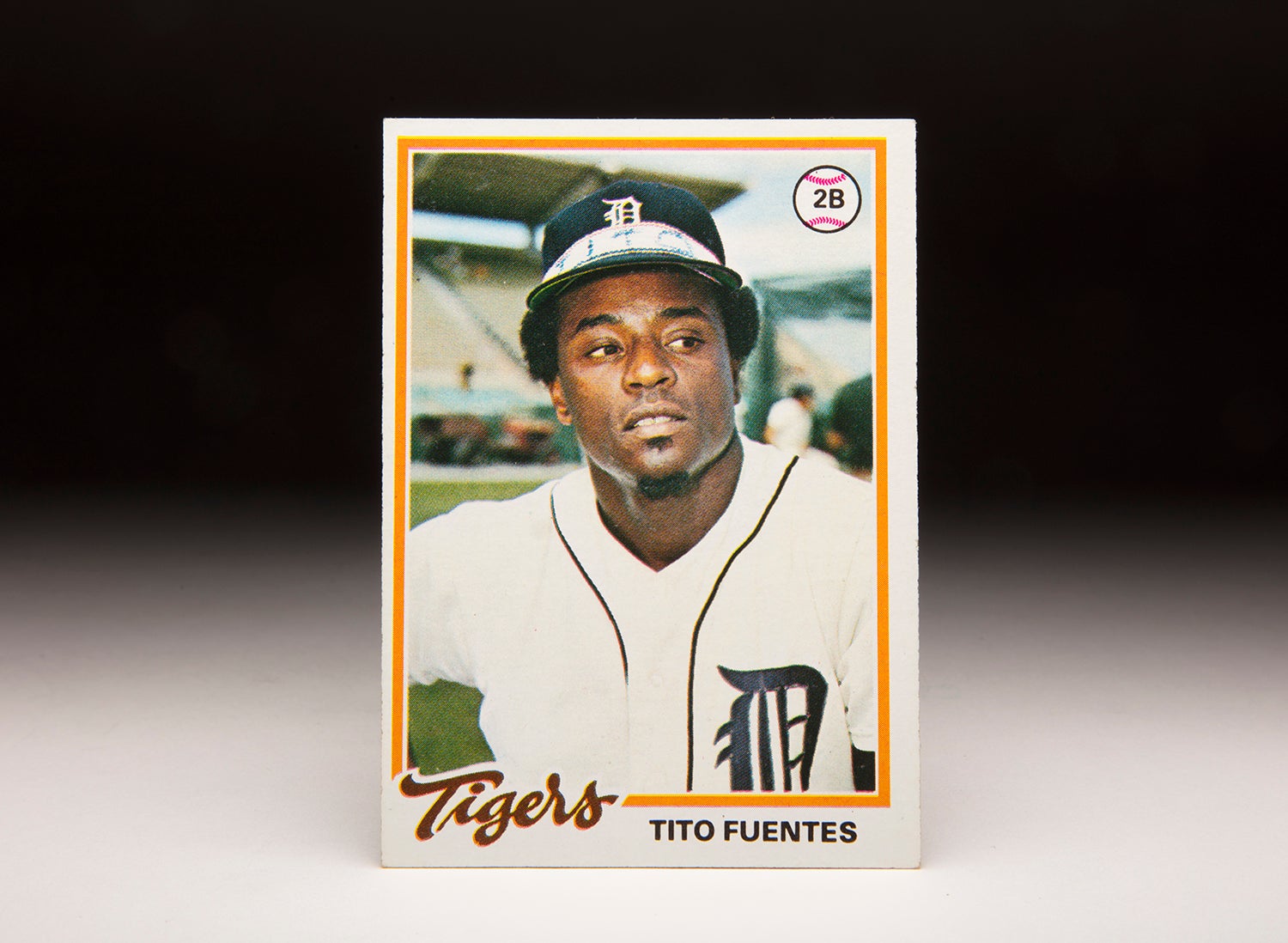

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Earl Williams

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

I sometimes wonder if ballplayers know that they might be posing for their final baseball card. Do players know that the end of the line is near? Or do they think that they have at least a couple of more seasons in them, no matter what?

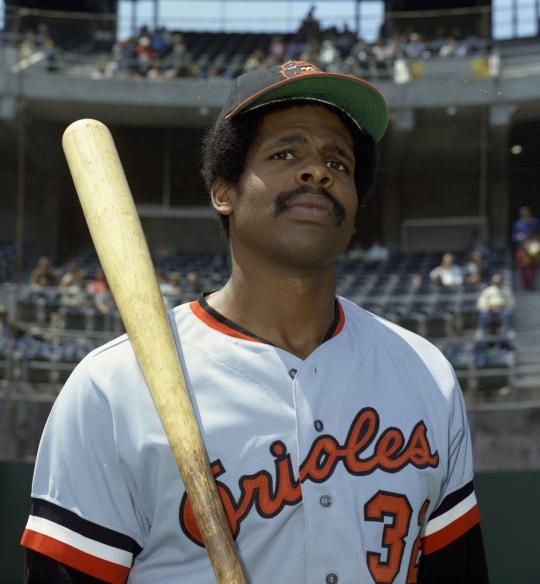

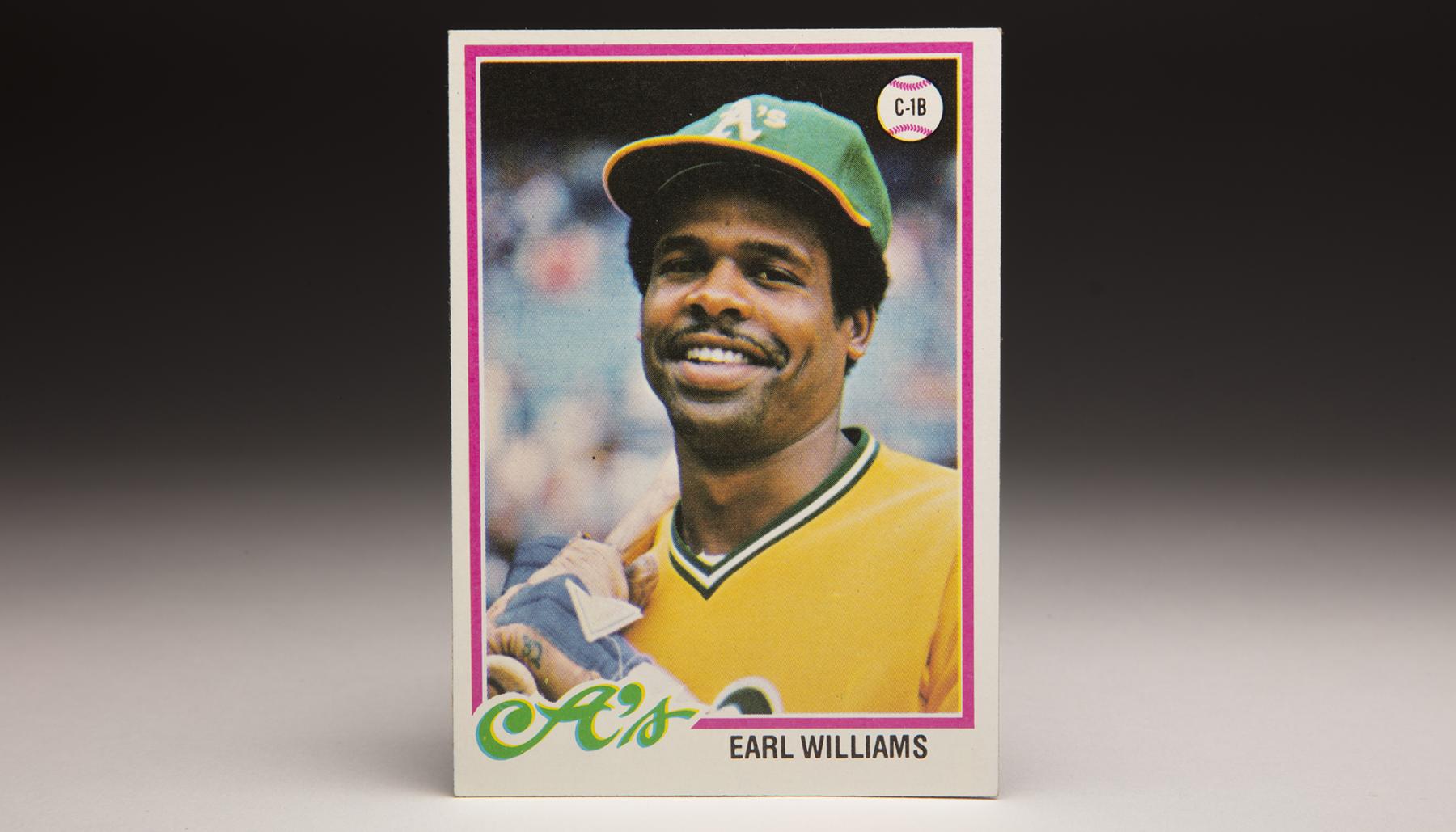

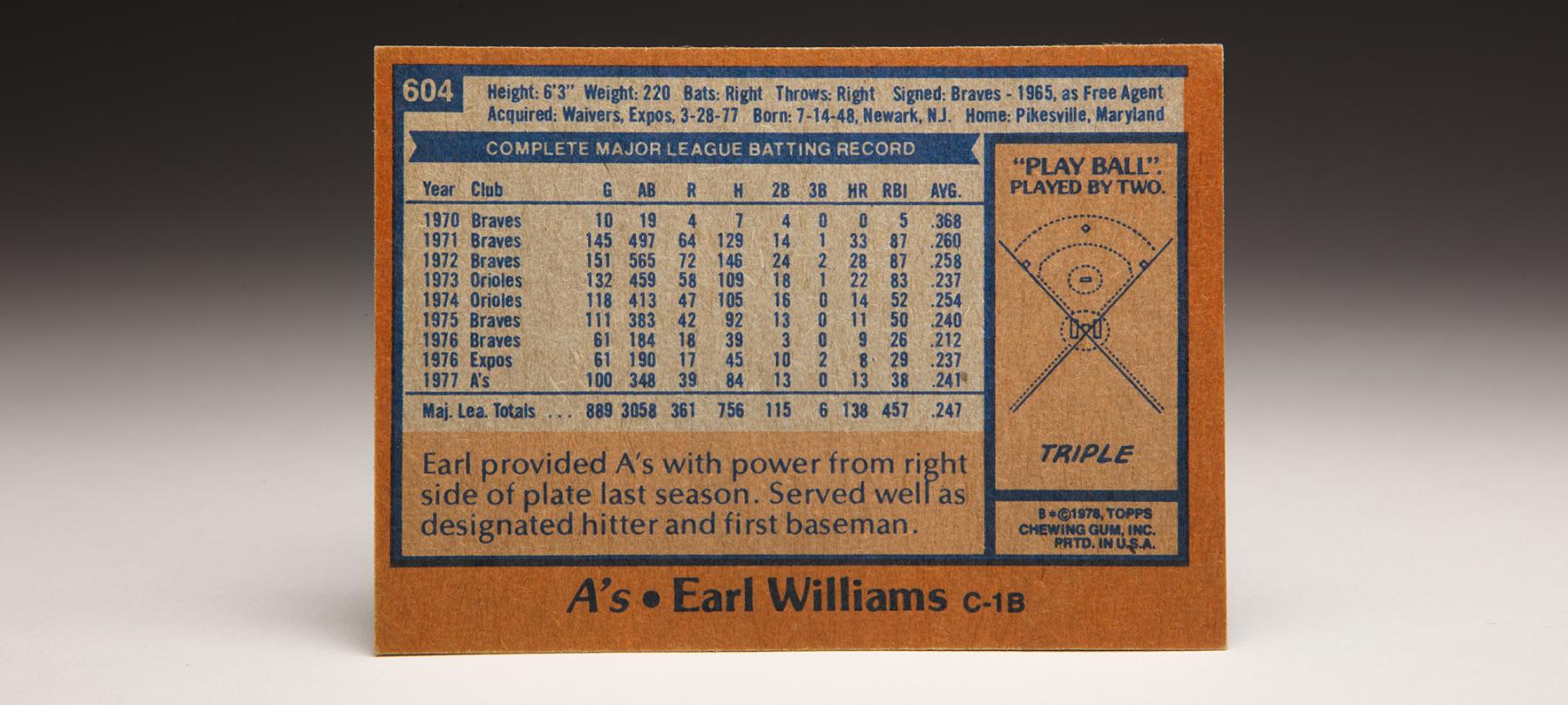

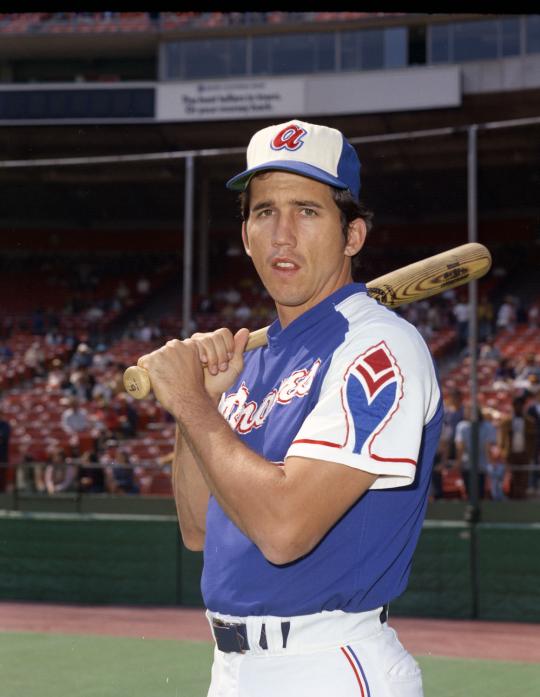

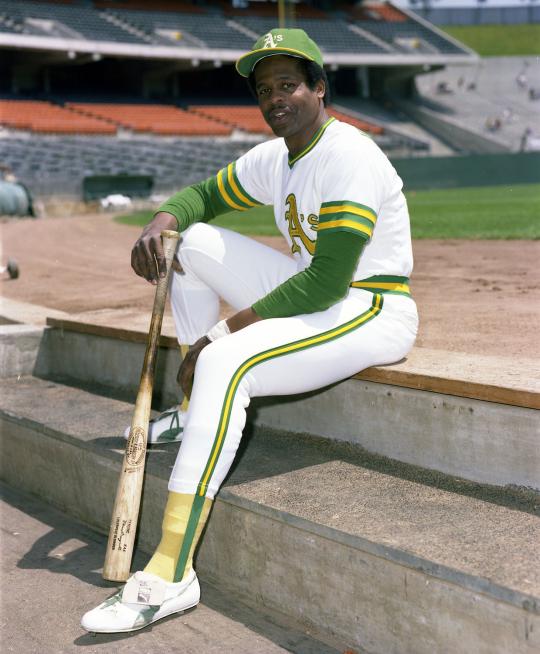

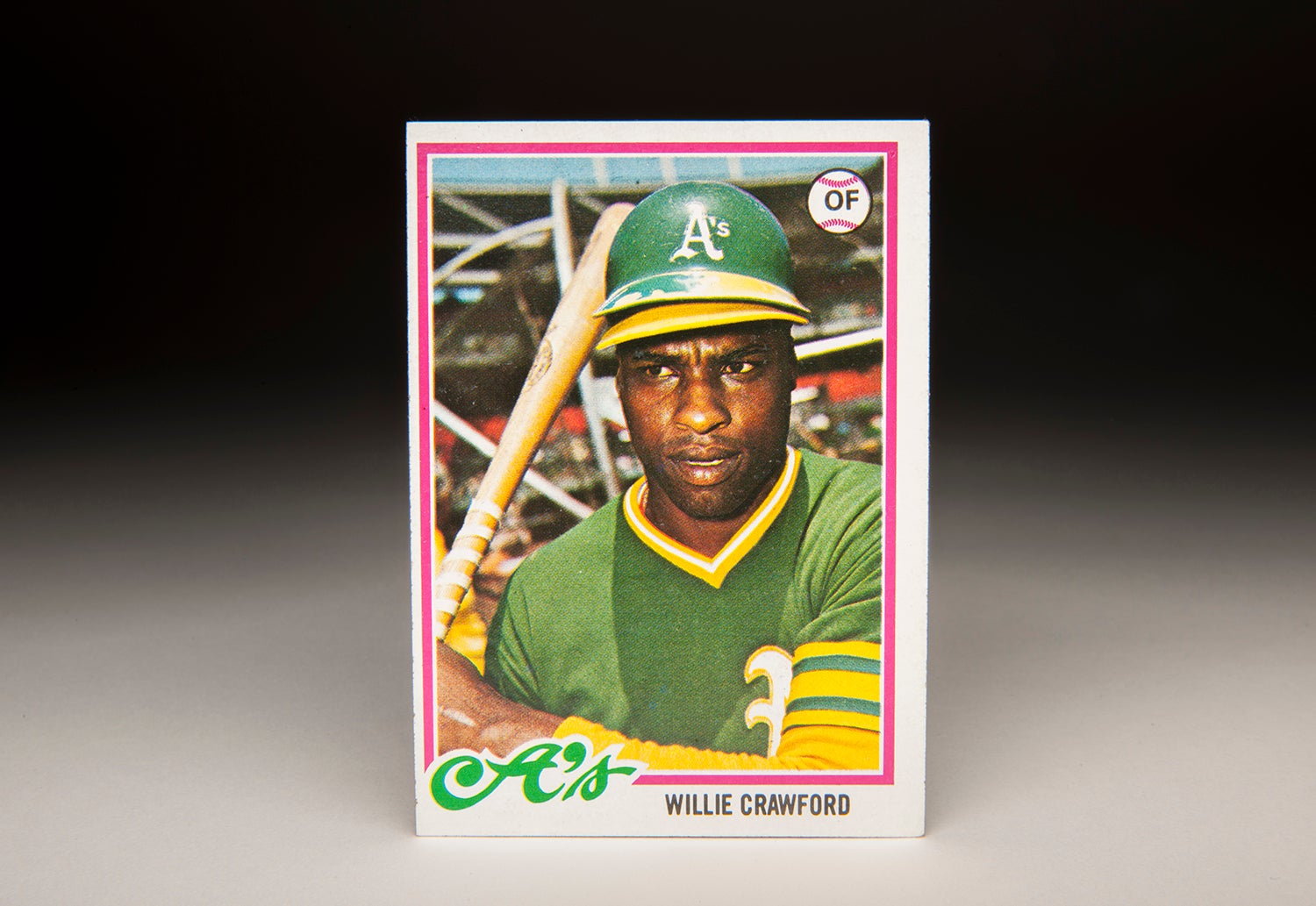

These questions come to mind when I look at Earl Williams’ 1978 Topps card. The photograph was taken sometime in 1977, maybe during Spring Training, or perhaps sometime during the season. Seen here wearing the gaudy gold top of the Oakland A’s, a team with which he is rarely associated, Williams is sporting a huge smile, free of care and worry.

Like a lot of players, Williams seems to be happy wearing a big league uniform. My guess is that Williams has no idea that the 1977 season will be his finale as a major leaguer. Although Topps would produce this final card for him in ’78, he would not appear in a single big league game that season – despite rather extreme measures on his part to continue his career.

Then again, Williams was one of the more intelligent players of his era; perhaps he did know that the end was coming. He was honest and well spoken, too, traits that sometime put him squarely into the center of the storm. At other times, he used his honesty to convey his sense of humor, making him one of the more interesting characters of the 1970s.

Williams’ professional journey began in 1965, the same year that Major League Baseball instituted a draft. The Milwaukee Braves selected him as a pitcher out of Montclair High School in New Jersey, taking the highly touted 17-year-old with the sixth pick overall. The Braves also agreed to pay for Williams’ college education, allowing him to take classes at Ithaca College before reporting late for a new season of ball.

In later years, Williams credited his classwork at Ithaca will helping him to become a good public speaker. “When I started college, I was majoring in English,” Williams told Bob Ibach of the Baltimore Evening Sun. Then I got into some broadcasting courses and really enjoyed it. Being able to speak is advantageous to an athlete. I feel I can convey my thoughts better.”

After wrapping up his classes in the spring of 1966, Williams began his pro career with the Braves, who had now relocated to Atlanta. Williams pitched in 11 games for Sarasota in the Gulf Coast League. He did well, but the Braves envisioned him as something other than a pitcher. Believing that he could hit with legitimate power, the Braves quickly moved him from the mound to first base.

Still a teenager, Williams struggled in his transition from pitching to hitting. Over his first three minor league seasons, he hit no more than seven home runs at any stop, and saw his batting average settle into the .230 to .250 range. The Braves remained patient. Even at the end of the 1968 season, Williams was still only 20 years old.

Then came the breakthrough. In 1969, Williams’ career course changed completely. Deciding not to attend classes at Ithaca in the spring of 1969, Williams reported to Spring Training with the rest of the Braves’ minor leaguers. The decision paid off. Playing at Double-A Greenwood for most of the summer, Williams bust out with 33 home runs and a .340 batting average. Williams became the stuff of legend at Greenwood, blasting several tape measure home runs. Atlanta’s front office took notice. Eddie Robinson, the director of the Braves’ farm system, compared Williams to Frank Robinson.

Williams delivered another good season in 1970, split between Double-A Shreveport and Triple-A Richmond. The Braves rewarded him with a late-season call-up and gave him a chance to play in 10 games. Williams did well in his initial cup of coffee, hitting .368. He appeared ready for a spot on the Opening Day roster in 1971.

The Braves initially planned to use Williams as a backup at first base and third base, positions manned respectively by Orlando Cepeda and Clete Boyer. The Braves needed depth at the infield corners because of Cepeda’s fragile knees and Boyer’s age. But Williams’ role changed when Boyer became involved in a bitter dispute with Braves general manager Paul Richards. Unable to reach agreement on a satisfactory contract with Boyer, Richards released the slick-fielding third baseman, opening up additional playing time for Williams.

Over the first two months of the season, Williams put in time at third base and first base. Then in late June, Braves manager Luman Harris told Williams that the Braves wanted him to become Atlanta’s No. 1 catcher. That might have been fine and well for some players, but Williams had never played the position in the minor leagues and had only dabbled in catching while playing in the instructional league and winter ball.

The idea came from Richards, the Braves’ GM and a man known for his willingness to innovate and experiment. “I saw this big, tough, rangy kid, and I also knew we didn’t have any catchers in the farm system,” Richards told sportswriter Paul Hemphill. The move made sense to Richards, but the Braves faced an obstacle: Williams didn’t really want to catch. Still, he had no intention of turning down the chance to become an everyday player, either. So he agreed to don the catching equipment and displayed an immediate adeptness for playing the position.

In particular, Williams showed off a knack for making strong throws to second base. As a hitter, Williams exhibited major power, and hit several home runs in clutch, late-game situations. His teammates noticed the trend and dubbed him “Big Money.” By season’s end, Williams had hit 31 home runs and posted a slugging percentage of .491. Those numbers helped him earn the National League Rookie of the Year Award.

Williams thought that his rookie success would translate into endorsement opportunities, but none came his way. In an interview with a reporter, Williams wondered out loud why no businesses, even local ones, offered him a chance. As an African American, Williams believed that racism was at least one of the reasons for the lack of commercial opportunities. As a result, Williams was branded as “militant” by some members of the media.

In 1972, Williams reported to Spring Training some 20 pounds overweight. Some of the Atlanta writers responded by nicknaming him “Fat Earl.” Shortly after the season began, Williams came down with migraine headaches, which forced him into a brief stay in the hospital. Despite these physical setbacks, Williams continued to hit with power (28 home runs).

But his catching suffered, in particular his ability to handle the knuckleballs thrown by staff ace Phil Niekro. For the season, Williams allowed 28 passed balls, with 21 of them coming while trying to handle Niekro’s knuckler. By his own admission, Williams acknowledged that he found catching difficult and uncomfortable. As he said rather famously to Sport Magazine, “My favorite position is batter.”

Even with his defensive problems, Williams blended well with new Braves manager Eddie Mathews and remained a promising talent. Other teams took interest in Williams, especially the New York Mets and Baltimore Orioles. The Mets reportedly discussed a deal involving their own catcher, Jerry Grote, and promising right-hander Gary Gentry. Rumors also began to circulate that O’s manager Earl Weaver badly wanted Williams as his new catcher. Weaver reportedly told his general manager, Frank Cashen, to approach the Braves and pursue Williams aggressively.

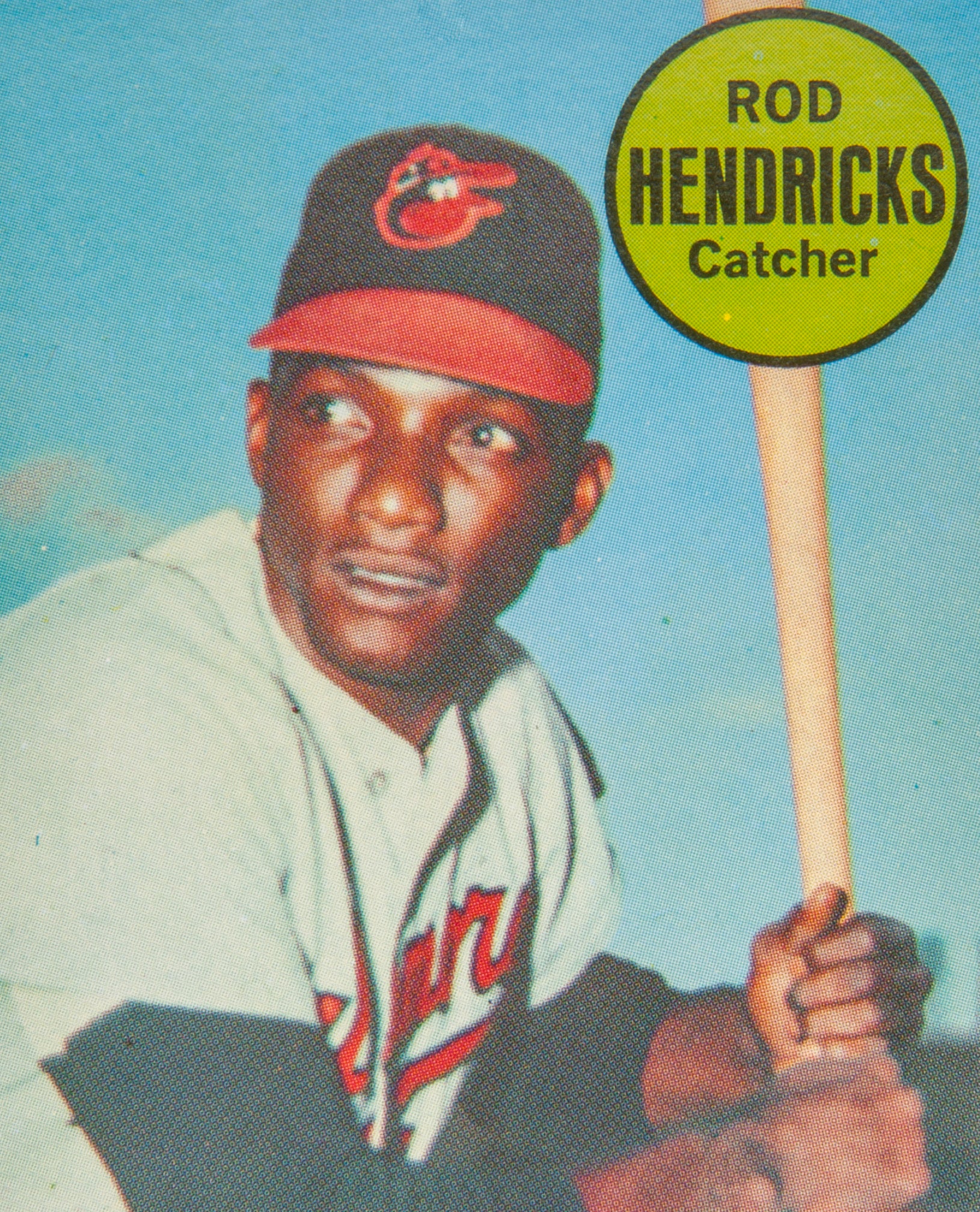

At the 1972 Winter Meetings, Cashen sat down with Paul Richards in an effort to hammer out a deal. The two men negotiated a blockbuster trade. Cashen agreed to give up a massive haul of four players – including power-hitting second baseman Dave Johnson, right-handed pitcher Pat Dobson, and catching prospect Johnny Oates – in a deal for Williams.

It was a huge haul of talent to surrender for Williams, but the Orioles were thrilled to have added a young home run hitter who would supply some of the power lost when the team traded Frank Robinson one year earlier. Clearly, the Orioles needed more power heading into the 1973 season, and had every reason to believe that Williams would supply it.

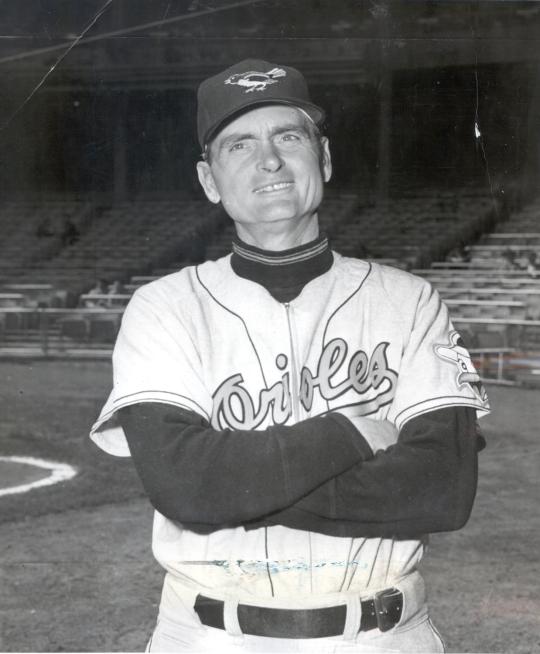

Unfortunately, Williams did not make a good first impression on Weaver. As was his usual habit, Williams showed up to Spring Training overweight, expecting to use the time in Florida to drop some of the excess poundage. Williams also tended to show up late to the ballpark, a habit that Weaver did not appreciate. In late June, Williams missed the team bus and received a one-game suspension.

Williams and Weaver also clashed when it came to pitch-calling and defensive technique.

The Orioles’ coaches tried to work with Williams on his catching, but he was reluctant to change. He also made it clear that he did not like to catch, and would prefer to play first base. That created a problem: The Orioles had no room for Williams there, not with Boog Powell around to handle the position on an everyday basis.

The difficulties extended beyond Williams, the manager and the coaches. At one point, friction developed between Williams and Andy Etchebarren, one of the other catchers with the Orioles. The tense atmosphere resulted in an uneven debut season in Baltimore. On the surface, Williams’ numbers looked good; he hit 22 home runs and drew 66 walks. But his slugging percentage, on-base percentage, and OPS all fell off from his 1972 levels in Atlanta. Williams’ catching regressed even further, making him a liability and undermining both the Orioles’ pitching and defense.

Williams’ play only worsened in 1974. His slugging percentage fell under .400, while his home run total dropped to 14. The situation seemed to hit rock bottom in one game, when Williams flied out with two outs and the bases loaded. Returning to the dugout, Williams unleashed a long tantrum, which reached such an extreme that Weaver saw fit to remove him from the game.

Even with all of the problems, Williams reported to his third Spring Training with the Orioles in 1975. Weaver included Williams on the Opening Day roster, but did not use his veteran catcher in any games. Rumors swirled that the Orioles would soon trade Williams to the Texas Rangers, a team looking for a starting catcher. On April 17, the O’s announced a trade, but it did not involve Texas. Instead, Williams was heading back to Atlanta for the modest price of a left-handed pitcher named Jimmy Freeman.

By now the Braves had a different owner: Ted Turner. A creative and rebellious sort, Turner announced that he wanted his players to wear their nicknames on the backs of their jerseys. Williams complied, but with his own twist. Rather than put his nickname, “Big Money,” on his uniform, Williams opted for the word “Heavy.” It was Williams’ way to poke fun at himself, while also having some fun with those who had criticized him for his habit of showing up to camp overweight. This was classic Williams.

Now in his second go-round with Atlanta, Williams was no longer a frontline player. The Braves viewed him as a backup catcher and first baseman. As a catcher, Williams made only 11 appearances for the Braves, instead playing more often at first base, where he shared time with Mike Lum. Williams did not give the Braves what they had anticipated; he hit only 11 home runs, the worst output of his career. After a poor start to the 1976 season, the Braves decided to move Williams, selling him to the Montreal Expos in a straight cash deal.

Williams put up mediocre numbers for the Expos, who brought him camp in 1977 but released him during Spring Training. Only a week later, Williams found work with the A’s. Owner Charlie Finley loved nothing better than to give brand name veterans a look later in their careers. When he saw that Williams was in shape, he gladly signed him to a contract, adding him to a roster that already featured several other players near the end of their careers, including Dick Allen and Manny Sanguillen.

On Opening Day, Williams found himself in the starting lineup as the designated hitter. Williams was ready to play, but he was also ready to talk. He saw that the A’s had a bad team and believed that the manager and coaches should share in the blame. At one point, Williams referred to the coaching in Oakland as “nonexistent.” Manager Bobby Winkles did not appreciate the critique. The A’s lost 98 games that season, but both Winkles and Williams lasted the entire season.

Both reported to Spring Training in 1978, but Williams was soon hit with a setback: A broken thumb. In May, the A’s waived Williams, who had yet to appear in a single game that season. When no other team showed interest, Williams was shocked. After all, he was still only 29 and still capable of catching. Not wanting to retire, Williams did something unprecedented. With the help of his mother, with whom he lived, he took out an ad in the New York Times. In the ad, Williams made himself available to any of the 26 major league teams. The ad included the following information: Salary: Very Reasonable Excellent Health-No Police Record Have Bat-Will Travel-Will Hustle. The part about having “no police record” typified Williams’ sense of humor.

While some teams chose not to take the ad seriously, at least one team showed interest. According to a report in the Sporting News, the Expos sent three wires (in the days long before email existed) to Williams. The Expos also left a phone message with his mother. For some reason, Williams did not respond to the Expos’ inquiries. So they signed another veteran catcher, Ed Herrmann, to a contract.

Williams decided to pursue another avenue for continuing his career. He signed a contract to play in the Mexican League, where he starred in 1979 and ’80. After his tenure in Mexico, Williams made news in an article written by New York Times writer Joseph Durso. Ever outspoken, Williams told Durso that he believed race had been a factor in keeping him out of the major leagues. He also admitted to some “immaturity” on his part, another factor in short-circuiting his career.

In spite of the controversial remarks, the Pittsburgh Pirates offered Williams a Spring Training invite in 1981. Williams accepted the invitation, but was unable to make the Pirates’ Opening Day roster. The Pirates did offer him a chance to play for their Triple-A affiliate at Portland, a team that was loading up with former big leaguers, including Luis Tiant, Larvell “Sugar Bear” Blanks and Rusty Torres. Williams thought about the offer, but decided to turn it down, officially ending his career. Williams left baseball completely and went to work for a pharmaceutical company, never to hold a job within the game again.

As a result, I did not hear much about Williams, until reading a note on the Internet in 2013 that said he had passed away after a diagnosis of leukemia. He was just 64. Like many other fans of 1970s baseball, I was saddened to hear that he had died at a young age.

Williams’ career in baseball involved sadness, too. Over his first two seasons in Atlanta, he looked so promising, to the point where some felt he would become one of the best power-hitting catchers of all-time. He did hit 138 home runs during a very respectable career, but fell well short of the expectations that teams like the Braves and Orioles once held.

Perhaps Williams’ career should serve as another reminder – and there are many in baseball history – that the game is tough and offers its players no guarantees. As Jimmy Dugan once said, “[Baseball’s] supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame