- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1982 Fleer Bill Robinson

#CardCorner: 1982 Fleer Bill Robinson

It was 10 years ago that baseball lost a good man in Bill Robinson.

Two themes always come to mind when I think about Robinson, who died suddenly and unexpectedly in 2007. First, he was that rare example of a player who performed better in his 30s than he did in his 20s. While most players reach their peak physically during their 20s, some need more time to adjust to the mental stress of playing at the highest level of professional baseball.

After struggling to find himself as an outfielder-third baseman with both the Atlanta Braves and the New York Yankees, Robinson became a productive left fielder for much of the 1970s and a key contributor to a world championship team. That adjustment took several years for Robinson, who didn’t start to succeed until his age 30 season with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1973.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Second, I’ll remember Robinson being prominently mentioned as a candidate to become the first African-American manager of the New York Mets, before Willie Randolph or Jerry Manuel, but never receiving that opportunity. Though a highly regarded hitting coach during the Mets’ successful run in the late 1980s, Robinson never received the call. Instead, he eventually found himself out of a job as a hitting coach and decided to switch careers, becoming an analyst for ESPN’s Baseball Tonight in the early 1990s.

At other times, Robinson was rumored as a strong managerial candidate in other locales, but it never worked out in his favor. It’s impossible to know if Robinson was a victim of racism or whether he simply interviewed poorly. Whatever the case, it seems that Robinson had the smarts and toughness to be a good major league manager. Sadly, that chance never came his way.

At the time of his death, Robinson was working as a minor league hitting instructor in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ organization. In the weeks leading up to his passing, he had been rumored as a candidate to become the Dodgers’ next major league hitting coach. It’s certainly possible that he would have been promoted to Los Angeles, although it’s likely that his window of opportunity to manage in the major leagues had passed. Robinson died at 64, an unlikely age for someone to receive his first chance at managing in the big leagues. Still, 64 is relatively young, and it’s possible that Robinson could have remained active in baseball for years – be it as a coach, a front office advisor, or even as a broadcaster.

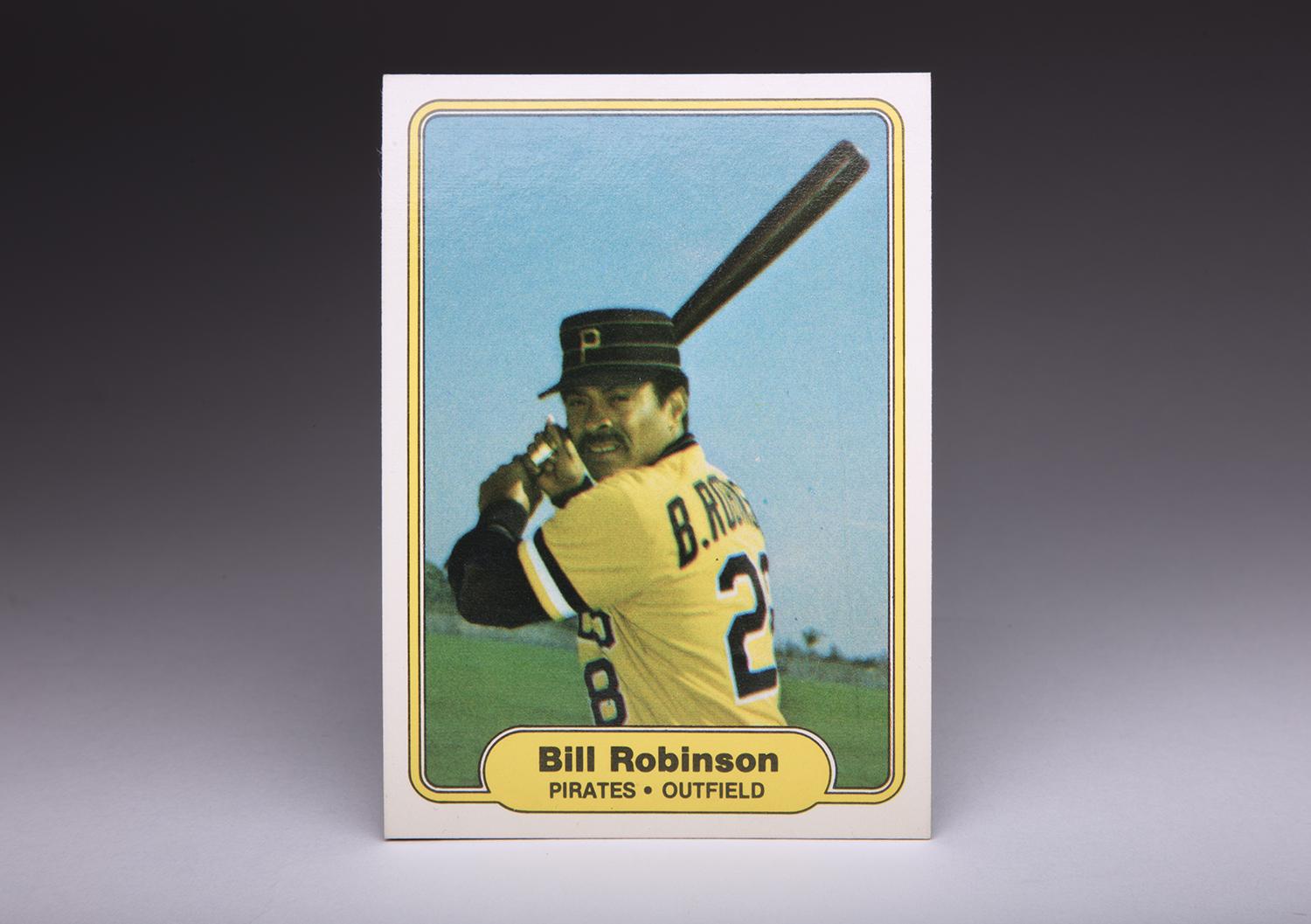

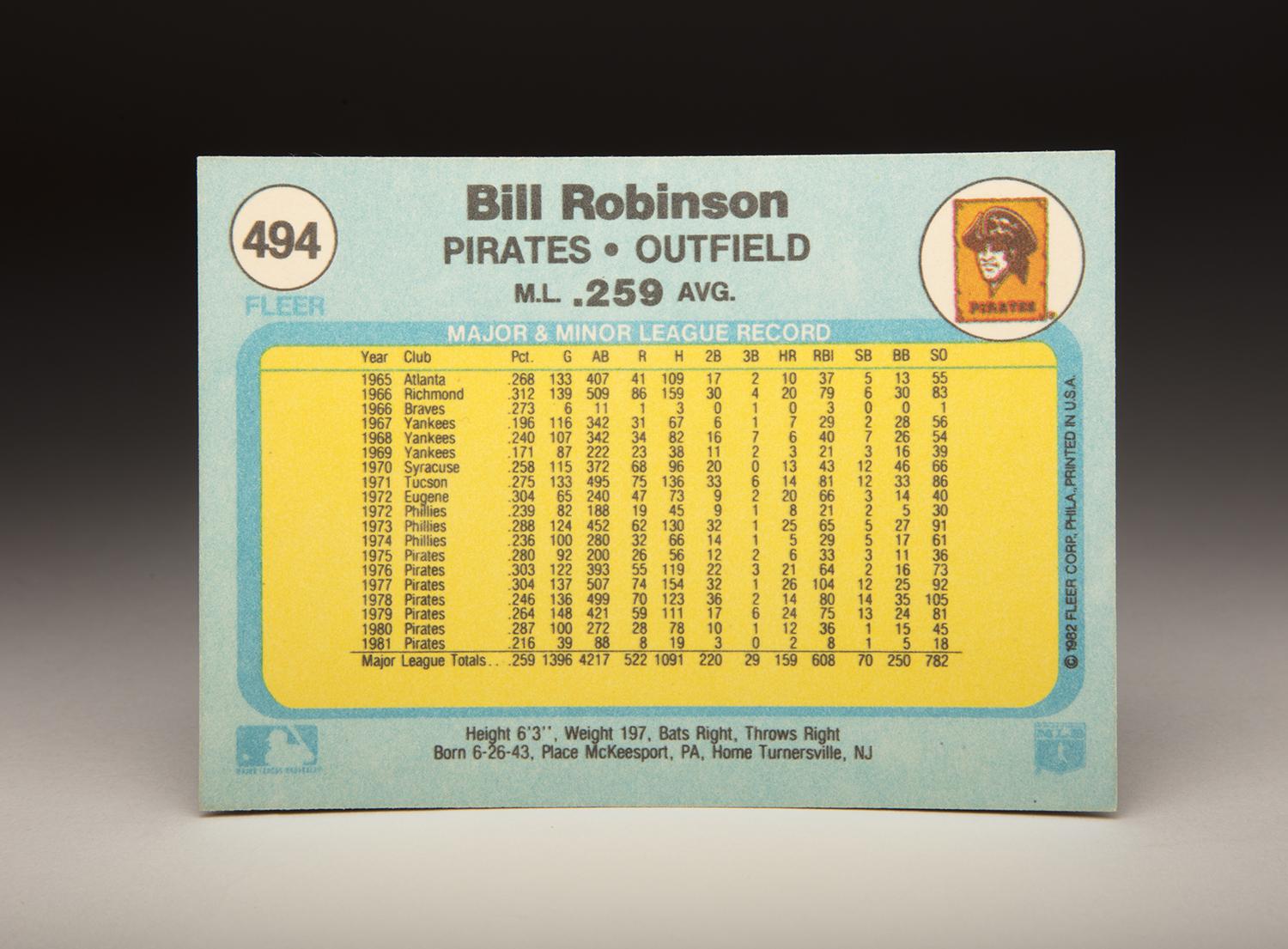

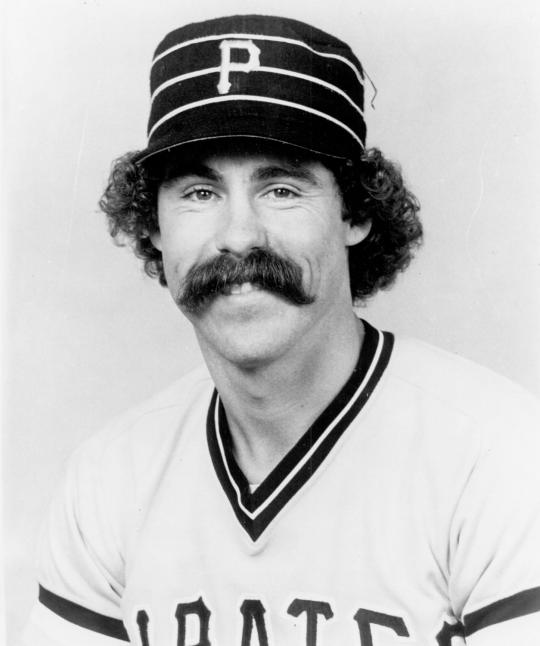

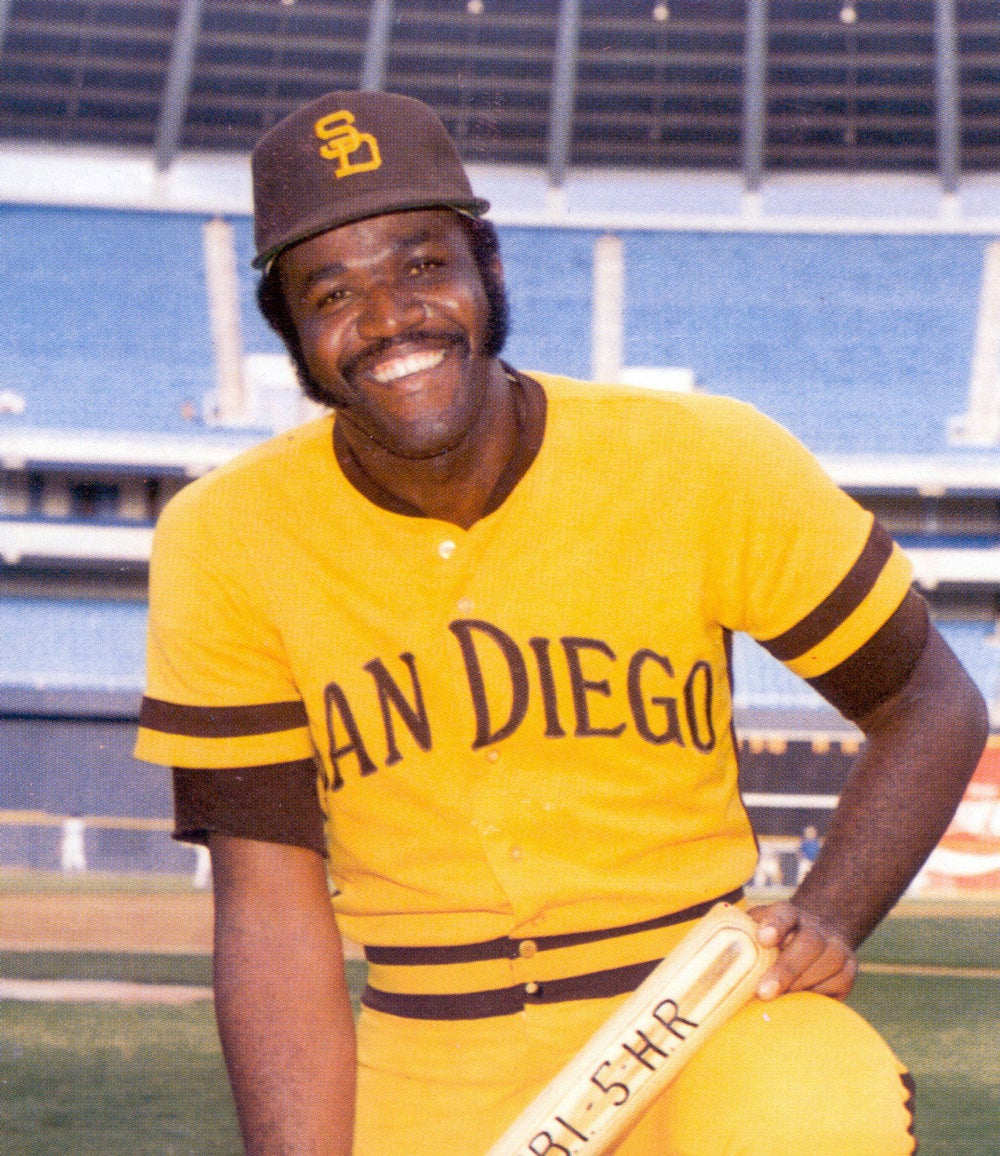

Of all the baseball cards that depicted Robinson during his long career in the game, perhaps the most distinctive was this 1982 release from Fleer. It is cropped in an unusual manner, off-center and top-heavy, barely showing Robinson from the waist up. It looks like Fleer was determined to include all of Robinson’s bat, which juxtaposes oddly against the sky blue background of what we might assume is a Spring Training day in Bradenton, Fla., the Pirates’ preseason home. The photo is also strange because of the background, which is not a flat practice field, but rather a hill. If this is indeed a spring training shot, it appears that Fleer’s photographer has chosen a remote location away from the practice fields and the ballpark. It’s hard to know exactly where this photo was taken; if the cameraman wanted to create the effect of snapping a picture in the middle of nowhere, he succeeded in achieving that goal.

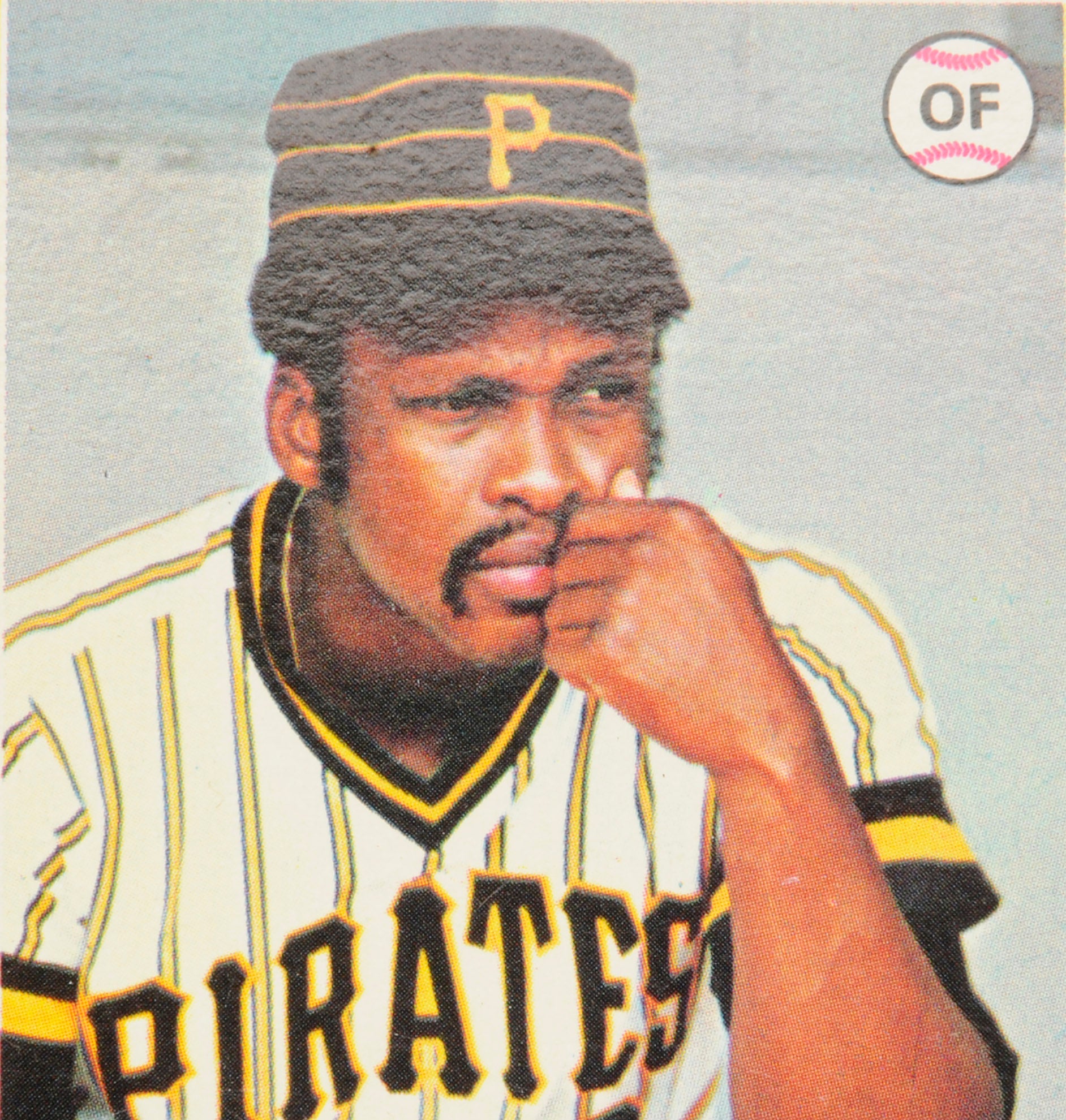

The 1982 Fleer card also gives us a full appreciation of the Pirates’ gaudy uniforms of the era. One of many combinations flaunted by the Pirates, this version features a bright yellow jersey, complimented by a bold, black number, and the player’s name, also in large typeface. In this case, the Pirates designated Robinson as “B. Robinson,” so as to distinguish him from teammate Don Robinson. And let’s not forget about those wonderful pillbox caps that the Pirates used in the late 1970s and early 80s, with their incredibly flat tops and the unusual horizontal lines that conjured up images of baseball in the 1800s.

Finally, we notice Robinson’s expression: Stern and professional, open-mouthed but without a smile. Giving us a Clint Eastwood-like squint, Robinson eyes the cameraman as if he were a pitcher. This is exactly how I remember Robinson: A serious ballplayer who meant business whenever he stepped into the batter’s box.

For Robinson, the business of baseball began in 1961, when he signed his first professional contract with the Milwaukee Braves. He would spend five seasons in the Braves’ system, flashing some power and hitting for average, but also enduring inconsistency in his play. He finally broke into the majors in September of 1966, but by then the Braves had departed Milwaukee; they now resided in Atlanta. Making his debut as a pinch-runner for Hank Aaron, Robinson appeared in six late-season games for the Braves and held his own at the plate.

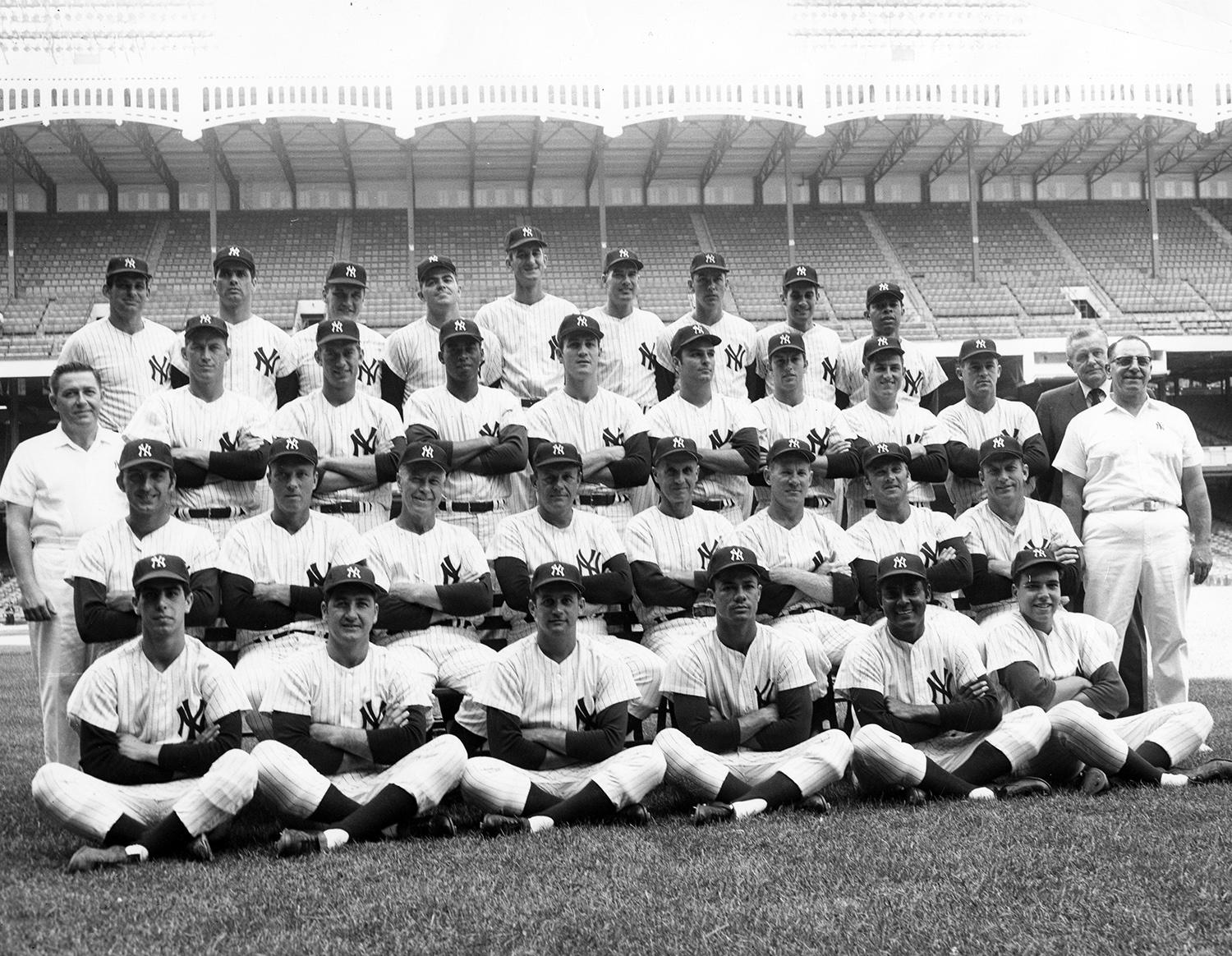

That would turn out to be the extent of his career in Atlanta. That winter, the Braves traded their 23-year-old prospect, sending him and pitcher Chi-Chi Olivo to the New York Yankees for established third baseman Clete Boyer. By now an aging team that needed to replace many of the key players from their “Bronx Bombers” glory days, the Yankees hoped that Robinson could successfully replace the departed Roger Maris in right field.

Yankees team president Michael Burke regarded Robinson as the great hope for the franchise. Wanting to market a new era in the team’s history and improve the club’s standing with the African-American community, Burke desperately wanted Robinson to succeed.

Facing enormous pressure in his Yankee debut in 1967, Robinson played right, center, and left field, but batted only .196 with a scant seven home runs in 116 games, hardly the kind of power production the Yankees desired from a starting outfielder. In fairness to Robinson, he secretly played much of the season with an injured shoulder, an ailment that required offseason surgery.

The Yankees continued to give Robinson chances over the next two seasons, but his hitting floundered. He didn’t hit for average or power, and had a tendency to swing at pitches outside of the strike zone. In 1970, the Yankees sent Robinson back to Triple-A Syracuse for the entire summer; in the minors, he batted only .258 with a mere 13 home runs and an OPS of .756. These were hardly the numbers of a prospect, not to mention the new face of the franchise. So after the season, the Yankees gave up, sending Robinson to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher Barry Moore.

Robinson would never appear in a game for Chicago. Instead, he spent all of 1970 in Triple-A, where he batted .275 with 14 home runs and 12 stolen bases, but he became frustrated when the White Sox refused to promote him. After one year in the Sox’ organization, Chicago sent him to Philadelphia for a minor league catcher/outfielder named Gerardo Rodriguez. Nobody knew it at the time, but the Phillies had just pulled off a lopsided trade in their favor.

After spending all of 1971 in the minor leagues, Robinson started 1972 at Triple-A, where he started to adopt a new philosophy and stopped worrying about factors outside of his control. Feeling more relaxed, he received the call from the Phillies in May. Playing the role of utility outfielder, he hit only .239, but did show some power, something the young Phillies needed as they looked to rebuild. In 1973, the Phillies gave Robinson a longer look, and watched him explode offensively. Belting 25 home runs and slugging .529, Robinson became the Phillies’ everyday right fielder, while also filling in as a left fielder and even as a third baseman. At the age of 30, Bill Robinson had finally arrived as an impact player.

Phillies manager Danny Ozark praised Robinson for his perseverance in turning around a career that appeared to derail with the Yankees years earlier. “I understood the problems he had in New York. He wasn’t sure of himself,” Ozark told Sam Smith of Black Sports. “Now he’s got the confidence. If he could go back 10 years, he would be another Aaron or Mays.”

As well as Robinson hit in 1973, he was bothered by a bad elbow that required offseason surgery. The following spring, Robinson reported to Spring Training and became dismayed when he learned that he would not be guaranteed a regular spot in the lineup. This revelation led to a blowup with Ozark, a misunderstanding that became somewhat overblown by the Philadelphia media. Perhaps bothered by the tension with his manager, and affected by a reduction in playing time, Robinson slumped in 1974 and fell into a secondary role with the Phillies.

The Phillies held onto Robinson that winter, but ultimately decided to make a change the following spring. On April 5, just days before the start of the regular season, the Phillies traded Robinson to the Pirates for oft-injured pitcher Wayne Simpson. The trade turned out to be the biggest break of Robinson’s career.

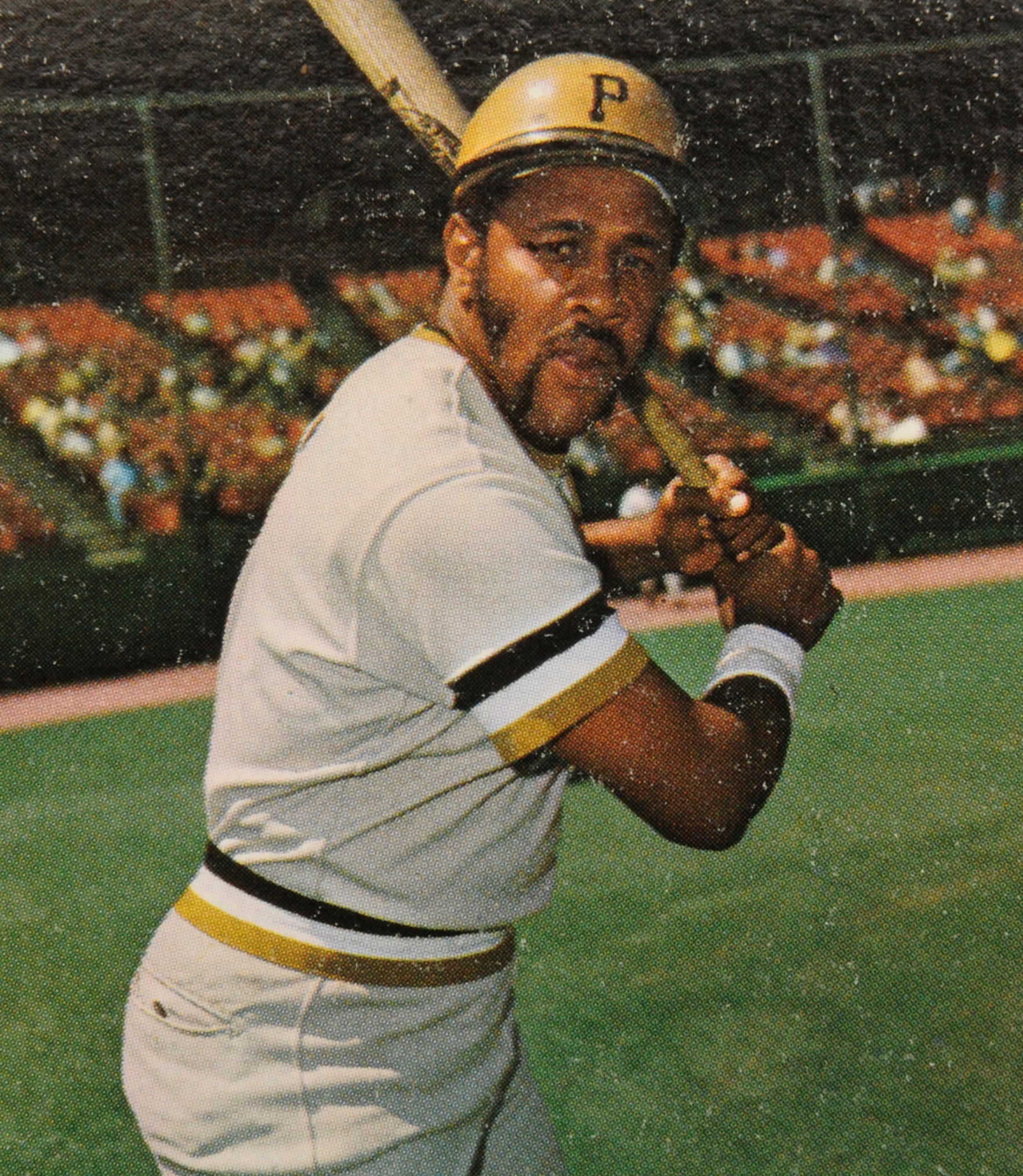

On paper, Robinson figured to fill a role as Pittsburgh’s No. 4 outfielder, behind starters Richie Zisk, Al Oliver, and Dave Parker. With a preponderance of left-handed hitters in his lineup, manager Danny Murtaugh found a role for Robinson playing fairly often against left-handed pitching. Robinson responded well to his platoon role, hitting a solid .283 with a more than respectable OPS of .763 and helping the Bucs to a division title.

In 1976, Robinson’s versatility opened up an avenue for additional playing time. In addition to playing his usual posts in the outfield, Robinson showed an ability to fill in at first base and third base. He became a supersub for Murtaugh, appearing at five different positions while hitting .303 and clubbing 21 home runs. With an OPS of .864, Robinson led the Pirates in that category. No Pirate was more valuable than Robinson, whose performance registered with the writers voting for the National League MVP Award. Robinson finished 21st in the balloting, a remarkable placement for a player who did not play one position on a regular basis.

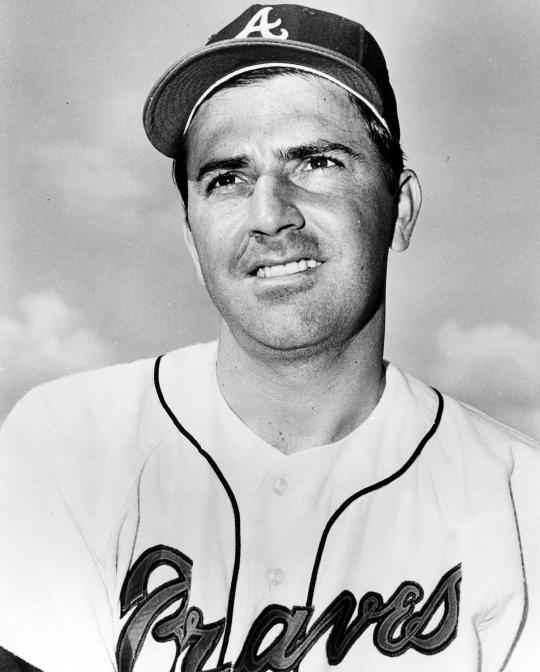

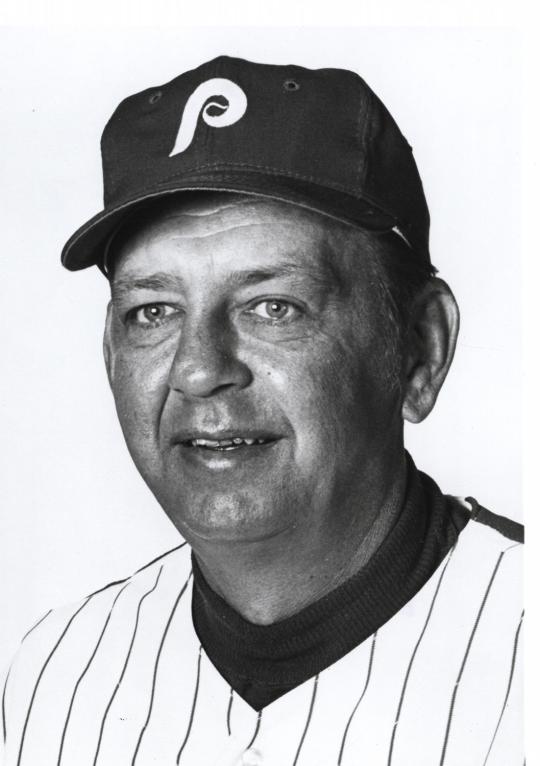

Although the Pirates told Bill Robinson that he would be their starting third baseman for the 1977 season, they ended up choosing Phil Garner, pictured above, a more natural defender at the hot corner. Robinson, however, would go on to have his best year in the big leagues in 1977 as a utility player for the Pirates. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Prior to the 1977 season, the Pirates told Robinson that he would be the Opening Day third baseman. That turned out to be a case of false hope, as the Bucs swung a deal for Phil Garner, a more natural defender at the hot corner. Rather than become upset at the news, as he had done with the Phillies, Robinson took the seeming demotion in stride. As it turned out, Robinson would receive plenty of playing time, thanks to a wave of outfield injuries. Keeping himself ready, Robinson turned in his finest season – coming remarkably at the age of 34. Playing even more frequently than he had in ’76, he hit .304, reached a career high with 26 home runs, and drove in 104 runs, the best figure of his career. Robinson placed 11th in the league MVP race, as he helped the Pirates win 96 games in a loaded National League East.

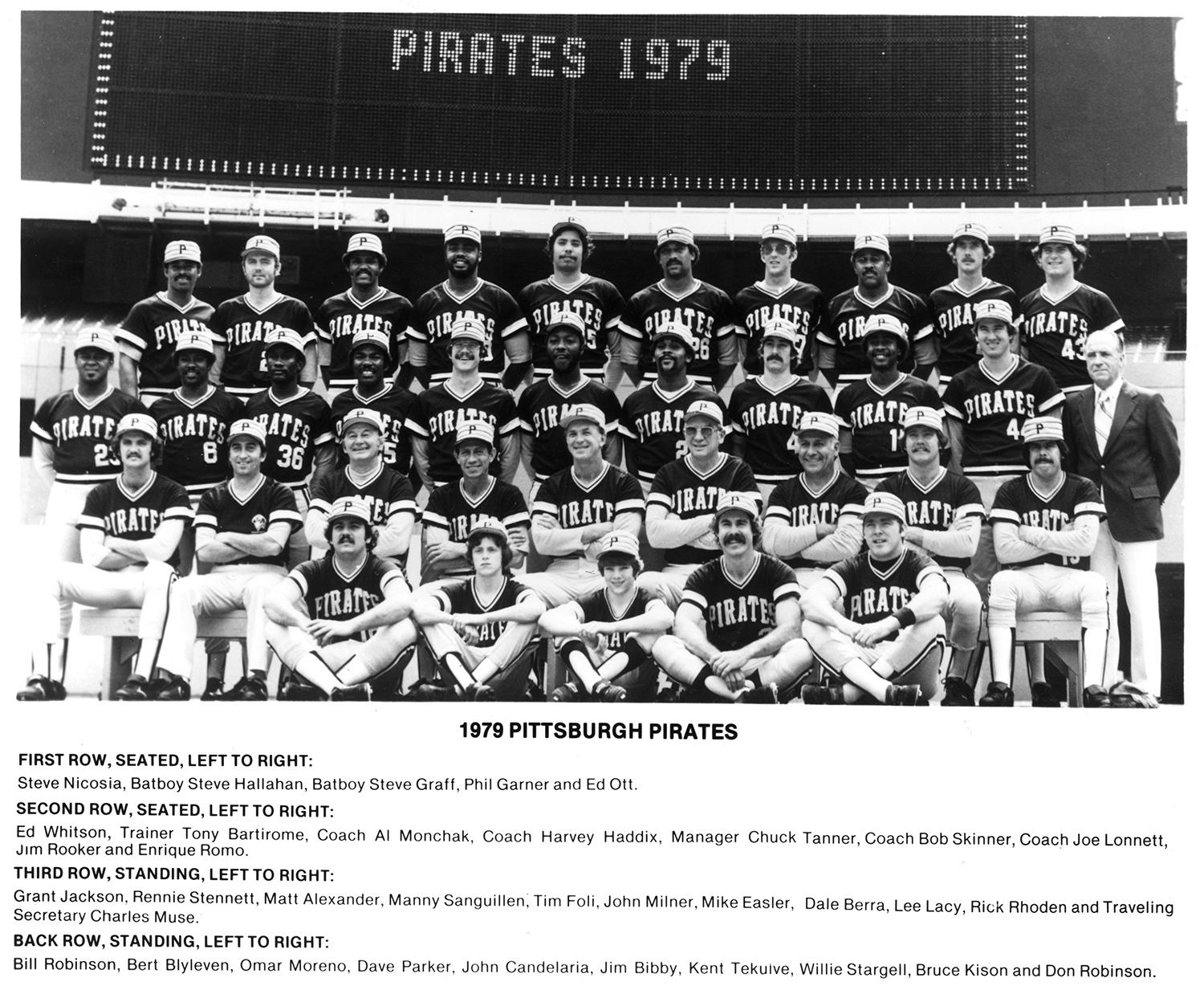

Robby would never again match the numbers of his career-best year, but he remained a major contributor in both 1978 and ’79. In the latter season, he played a career-high 148 games as the Pirates’ regular left fielder, while lengthening a lineup that also had Bill Madlock, Willie Stargell and Dave Parker. Robinson’s 24 home runs, along with his continuing professionalism in the clubhouse, made him one of many crucial supporting actors on a deep and talented Pirates team.

For the first time in his career, Robinson played on the national stage of the World Series. He batted a respectable .263 against the vaunted pitching of the Baltimore Orioles, as the Pirates added a second World Series title to their collection from the 1970s.

Robinson remained a productive player for the Pirates in 1980, but age finally started to take its toll in ’81, when he turned 38. After a slow start to the 1982 season, the Pirates dealt him, sending Robby back to Philadelphia for a younger outfielder, Wayne Nordhagen. The trade came with sadness, given the level of respect that Robinson had attained in the Pirates’ clubhouse.

“Bill Robinson is one helluva man,” Hall of Famer Willie Stargell told Frank Dolson of the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Nothing but a plus in anybody’s life. He is a caring, concerned man.”

Although he played sparingly for the Phils over parts of two seasons, he made a contribution as a counselor to some of the team’s younger players, especially right-handed pitcher Charles Hudson. Robby remained with Philadelphia until June of 1983, when the club released him. Now 40 years old, he had extracted every bit of baseball life from his body.

Robinson did not remain out of work for long. The following season, the New York Mets hired him as their batting coach. Robinson put in long hours with Darryl Strawberry, among others, while garnering a reputation as one of the game’s best and most thoughtful hitting instructors. Two years after joining the Mets, Robinson picked up his second World Series ring, as the Mets outlasted the Boston Red Sox to win the world championship.

Remaining with the Mets through 1989, Robinson lost his job at the end of that season. He turned to broadcasting, doing studio work for ESPN for a couple of years, before returning to an on-field job with the San Francisco Giants as a minor league manager. He guided Double-A Shreveport to a league title, but failed to move up within the Giants’ system and returned to the Phillies’ organization as a minor league hitting instructor. From there, he did work for the Triple-A affiliate of the Yankees, who were so appreciative of what he did for their young prospects that they gave him a World Series ring in 1999.

Robinson then returned to the major league level as a coach with the Montreal Expos and the Florida Marlins, earning another World Series ring with the latter franchise in 2003. He later joined the Dodgers’ organization as a roving minor league hitting instructor. While on assignment to Las Vegas in 2007, Robinson’s lifeless body was found in his hotel room. To this day, the cause of his death remains unknown, though he had suffered from diabetes for years.

By the time that he joined the Dodgers, Robinson had given up hope of becoming a major league manager. Some within the game have speculated that race played a factor, a possibility that Robinson acknowledged, but he refused to become bitter about the situation. His comments in 1998 to sportswriter Vic Ziegel reflected his positive state of mind.

“It’s been fun, gratifying to help young kids,” Robinson told Ziegel. “I had delusions of being a major league manager, but I know that’s not going to happen. Baseball doesn’t owe me a thing. As long as I have a uniform on, I’m grateful. I’ve been successful. Maybe not in a material way, but I have the Lord on my side and my family. What more could a man ask?”

A man who could have called it quits, Robinson finally found himself at the age of 30, went on to play 16 seasons, and earned four World Series rings as a player and coach. For Bill Robinson, that was plenty good enough.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum