- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Topps Mitchell Page

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Mitchell Page

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Some players stand out on their baseball cards. They have a distinctive look that separates them from just about everyone else. If you saw them play, you don’t need to see their names on the card to know who they are.

Mitchell Page was one of those players.

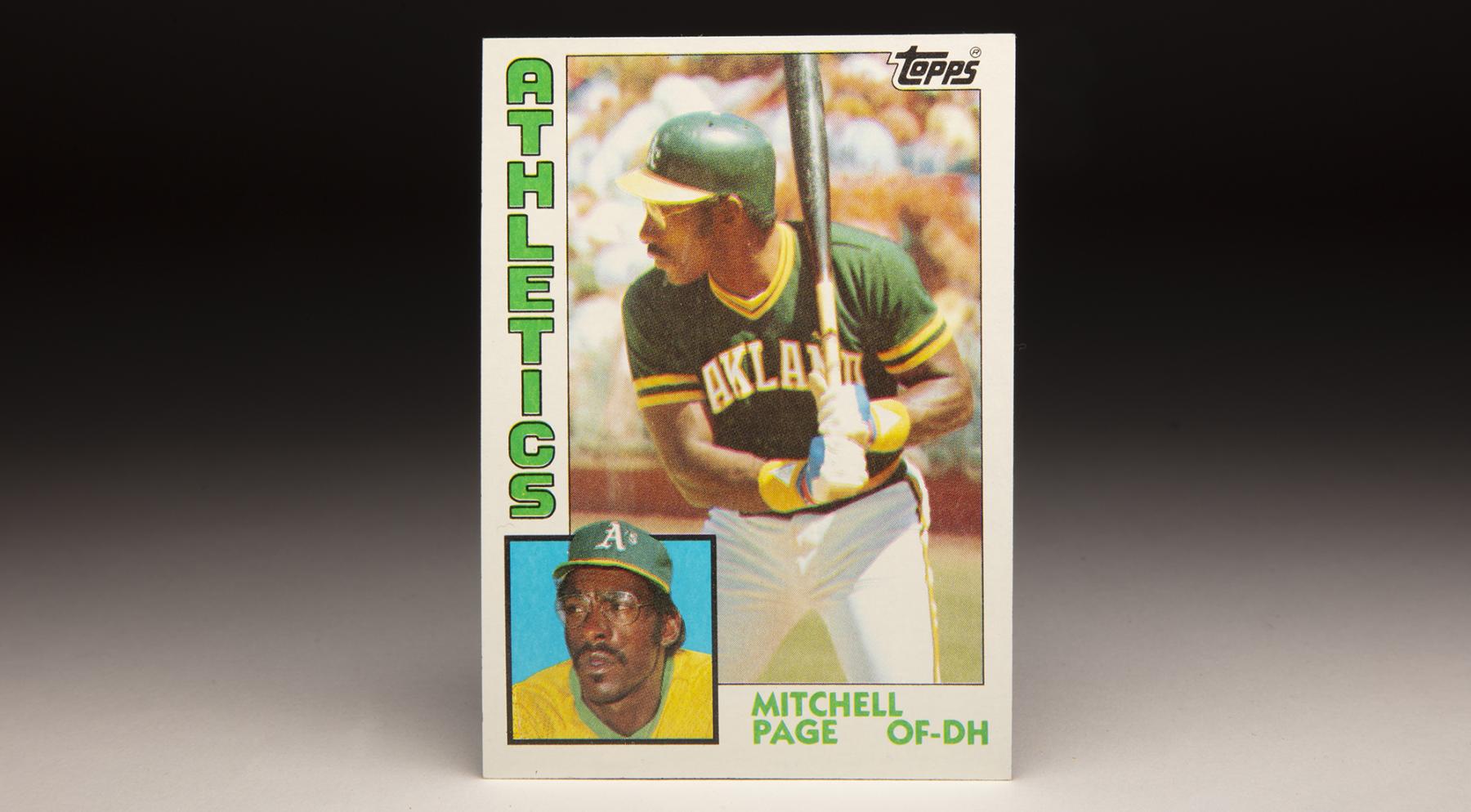

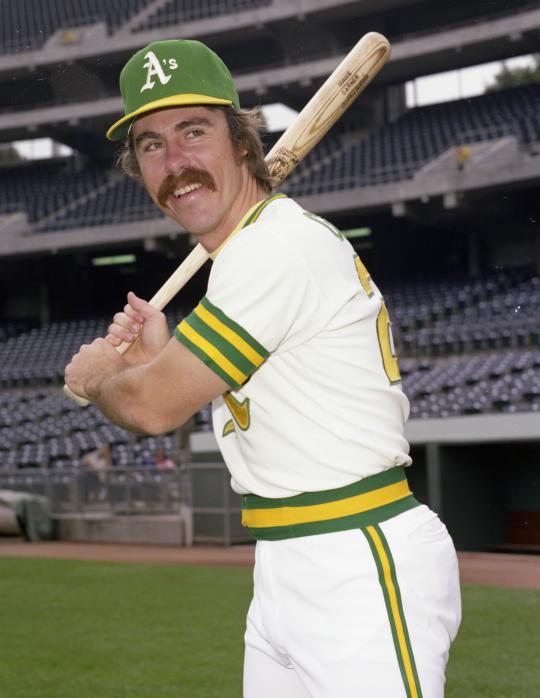

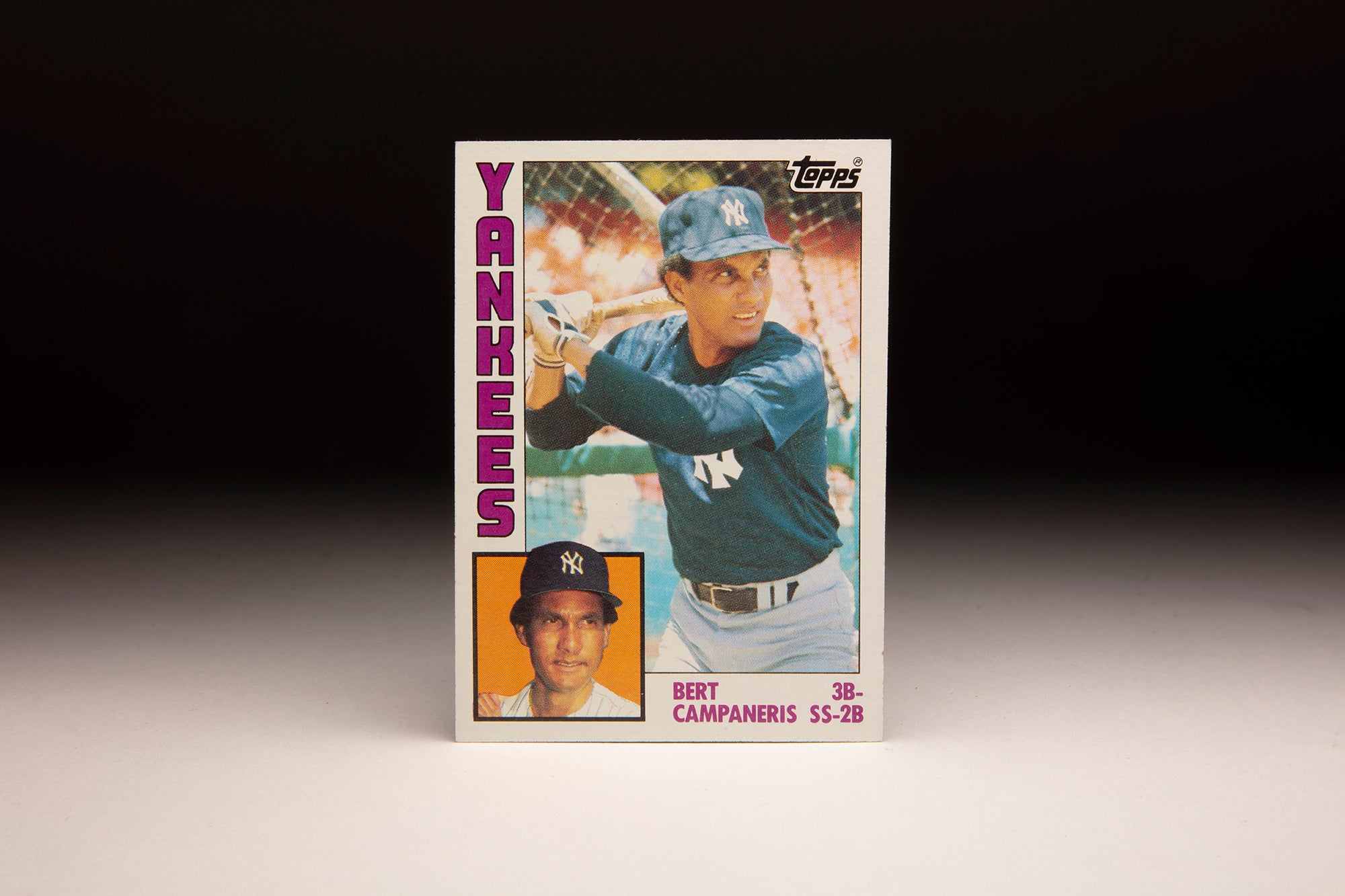

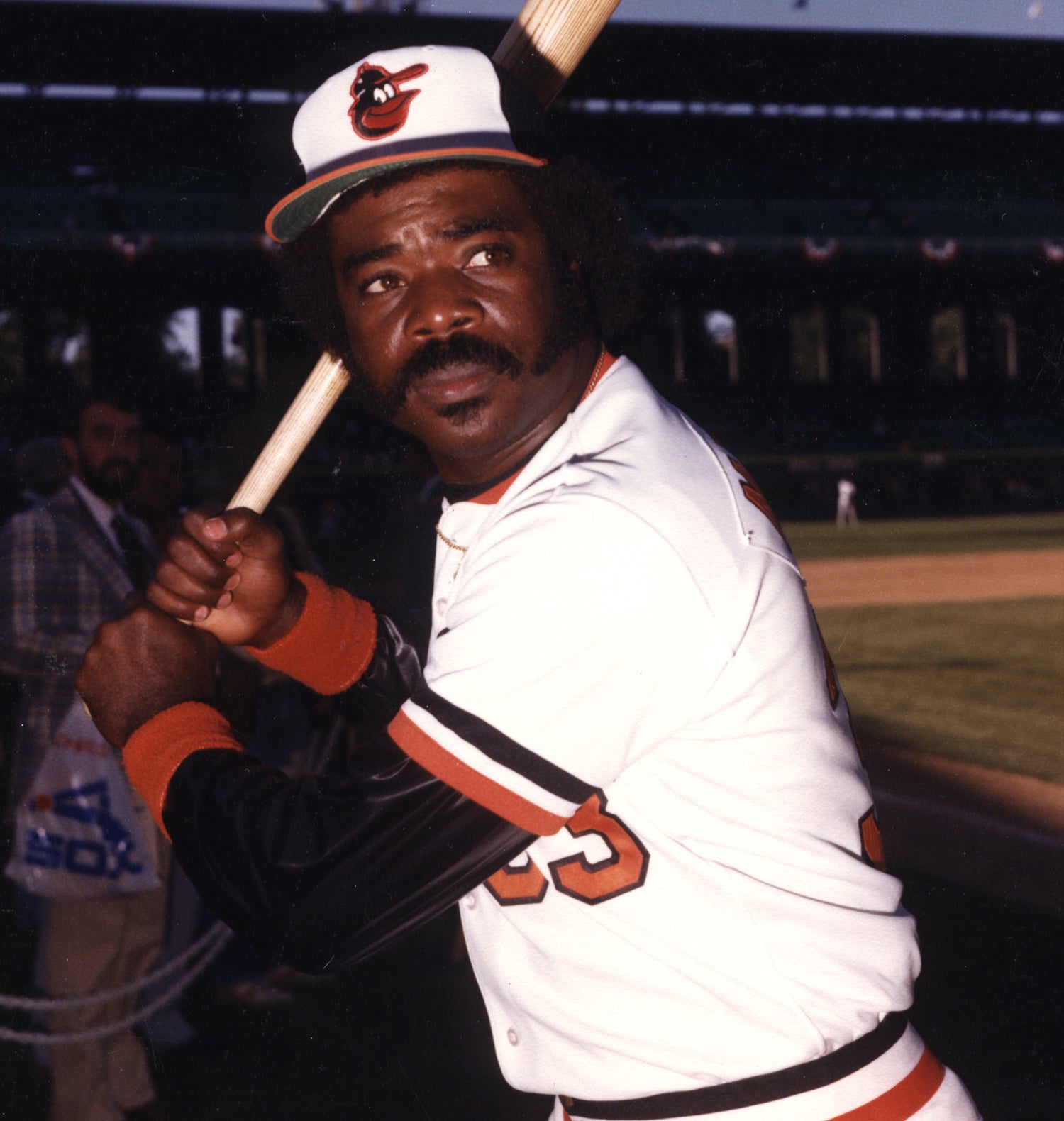

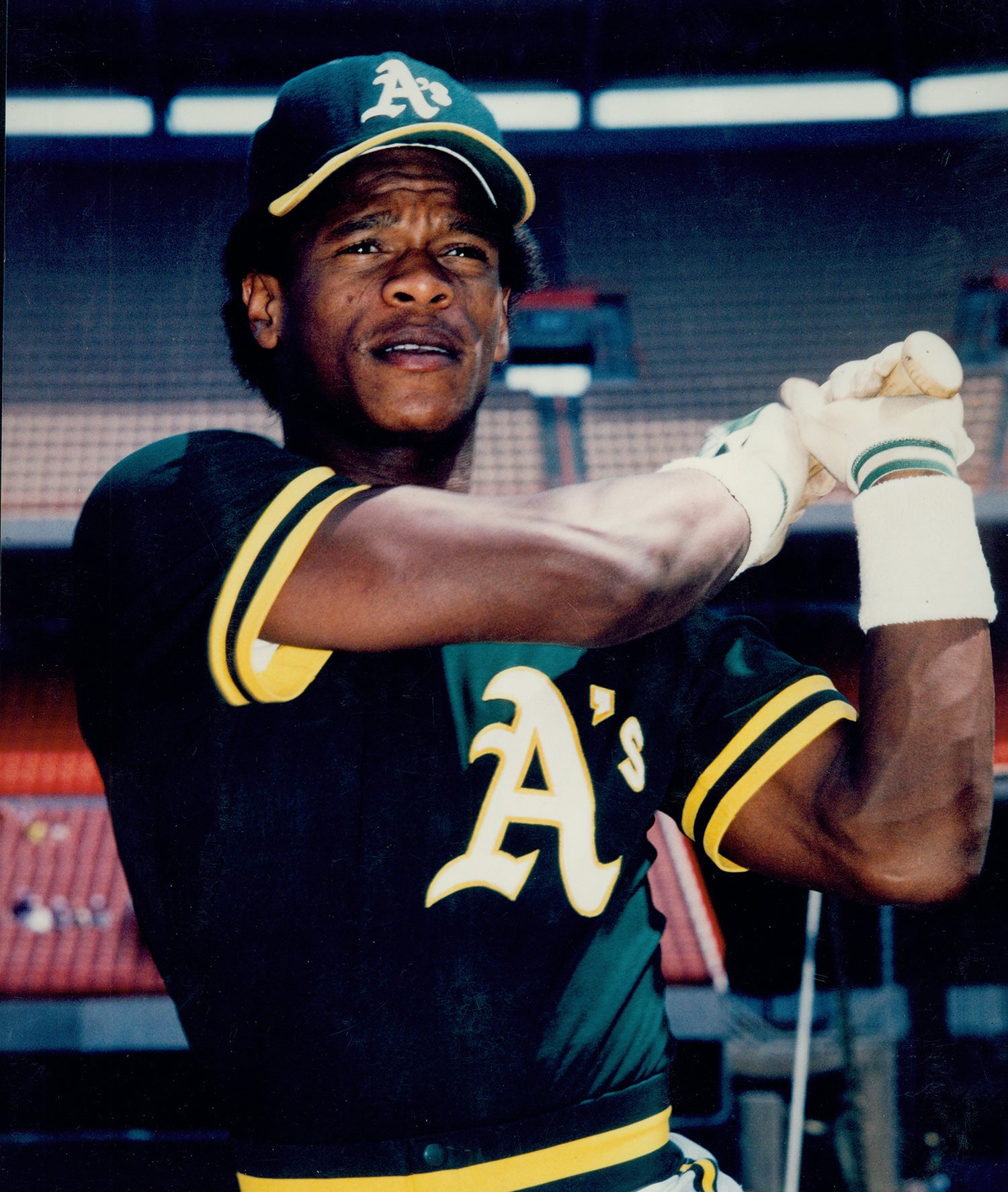

Page’s 1984 Topps card, through its primary action photograph and the smaller portrait, gives us an indication of his unique appearance. With his large head, prominent chin, and ruddy face, Page could easily be picked out of a crowd. Additionally, he almost always wore glasses or dark sunglasses – large, wire-framed eye wear that was very much in style in the 1970s and 80s.

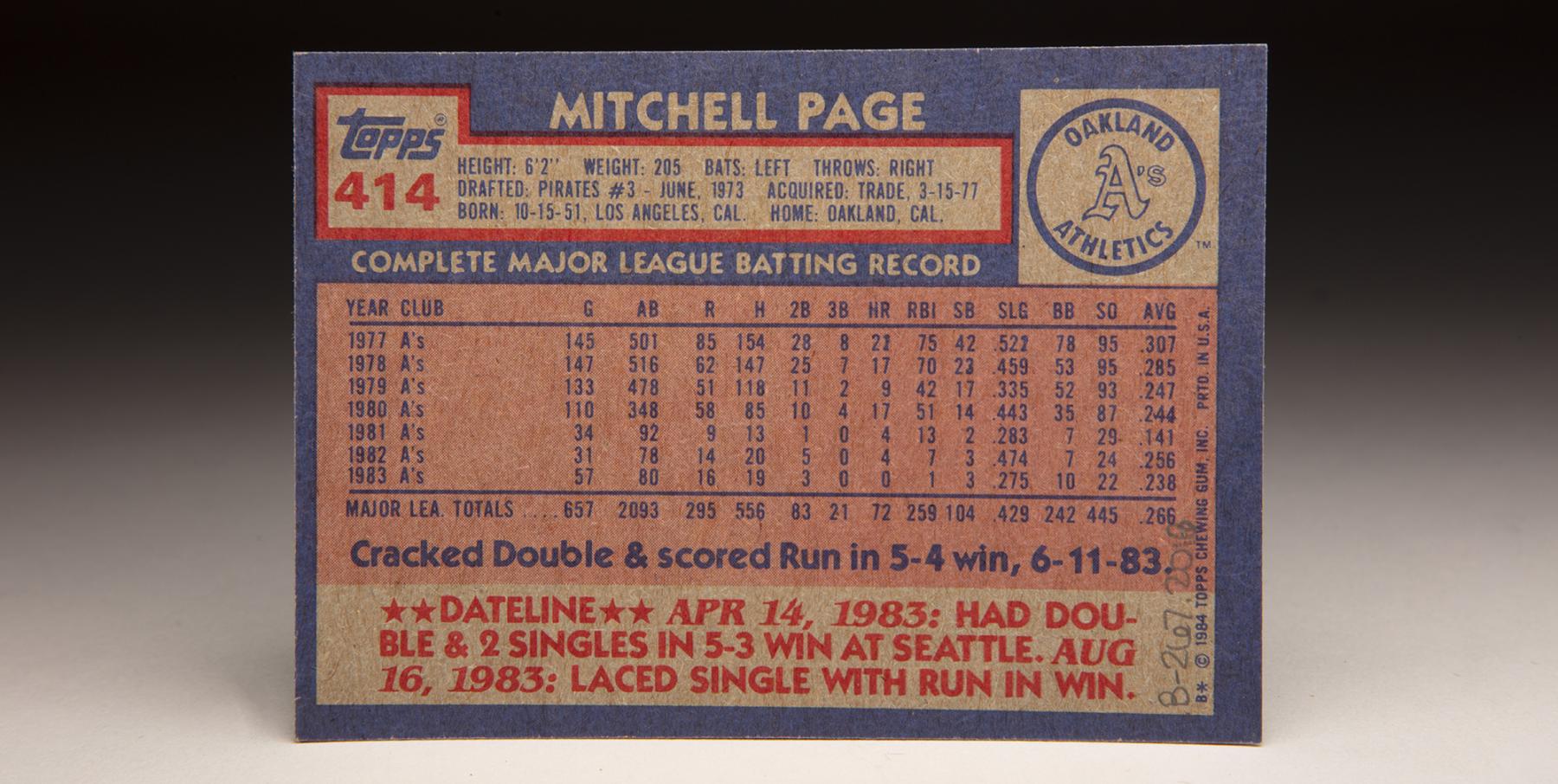

Page had a rugged physique, too. He had wide shoulders and heavily muscled arms, which were accented by bright yellow wristbands. At a time when few players did any kind of serious weight lifting, Page looked like one of the strongest players of his era. Oakland’s unusual green road uniform completed the look of a player who could be spotted hundreds of feet away.

Fourteen years before he appeared on this Topps card, Page seemed to be on the verge of beginning his association with the A’s. They took him out of Compton Community College in the fourth round of the January phase of the draft. But Page opted not to sign, instead continuing his college education and delaying his eligibility to be drafted again until 1973. That’s when the Pittsburgh Pirates selected the lefty-swinging outfielder in the third round of the June draft. This time, Page signed and received an assignment to Charleston of the Western Carolinas League. He played in only 18 games there before being bumped up to Salem of the Carolina League, where he finished out his first professional season.

The Pirates kept him at Salem all of 1974. He played well there, hitting .296, drawing 70 walks and hitting 17 home runs. He also stole 15 bases. With his combination of basestealing speed and home run power, Page vaulted to near the top of the Pirates’ prospect list.

In 1975, Page received a promotion to the Double-A Texas League, where he put up even better numbers against higher-level pitching. With an OPS of .906, 23 home runs, and 23 stolen bases, Page was ready to move up again in 1976. He played for the Charleston Charlies, the Triple-A affiliate for the Pirates, and posted similar power and speed numbers, while also making the transition from the outfield to first base.

There was little doubt that Page was ready to play in the major leagues by 1977. Unfortunately, he faced obstacles in Pittsburgh. Page was a first baseman and corner outfielder; the Pirates were already well-stocked with Willie Stargell and Bill Robinson at first base, Al Oliver in left field, and Dave Parker in right field. There was simply no place for Page to play on a regular basis.

Page reported to Spring Training with the Bucs in 1977, but he would not break camp with the franchise. On March 15, the Pirates pulled off a blockbuster trade that filled a need at third base. In acquiring Phil Garner (along with veteran infielder Tommy Helms and pitching prospect Chris Batton), the Pirates had to surrender an enormous package of six players. The boatload of talent included Page, along with fellow outfield prospect Tony Armas and pitchers George “Doc” Medich, Rick Langford, Dave Giusti and Doug Bair.

While the Pirates were a good team replete with quality outfielders and first basemen, the A’s were facing a down period after their glory years of 1972, ’73 and ’74. They needed young talent just about everywhere on the diamond. The A’s featured several brand-name veterans, but most of them were players past their prime, including former Pirates Giusti, Medich, and Manny Sanguillen, along with other veterans like Dick Allen, Earl Williams, Willie Crawford, and Stan Bahnsen. Five or six years earlier, these players might have made the A’s a contender. But now they were just part of a team that had seen better days.

Faced with a mammoth rebuilding task, A’s manager Jack McKeon installed Page as his starting left fielder. Not surprisingly, Page stood out as a bright spot on a team that came close to losing 100 games. Still only 25, Page hit 21 home runs, stole 42 bases and drew 78 walks. He posted an OPS of .926, impressive for any player but phenomenal for a rookie. By the end of the season, McKeon was comparing Page to a recently retired American League star who had won two batting titles.

“He reminds me a great deal of Tony Oliva,” McKeon told Fred McMane of Baseball Quarterly. “Oliva had the knack of being able to use the entire field. He was very difficult to defense.”

In the meantime, Oakland fans felt that Page’s first-season numbers were good enough to earn him Rookie of the Year honors, but American League writers instead gave the award to Baltimore’s Eddie Murray. Page settled for second place in the voting.

From the start, Page became a popular player with Oakland fans. Longtime A’s broadcaster Monte Moore dubbed him “The Swingin’ Rage,” a colorful nickname that rhymed with his last name and caught on in the Bay Area. Page always seemed to have a smile on his face, whether in the outfield or on the base paths. He also took time to talk to fans, conversing with them regularly before games.

Given his popularity and talent, Page seemed like a player whom the A’s could build around. But like a lot of young players, he didn’t perform as well in his sophomore season. He had a productive year in 1978, but his home runs, stolen bases, and batting average all fell off from his rookie standards. He also took some criticism for being out of shape, with the extra weight affecting his speed and defensive play. A preseason injury to his foot, where he incurred bone chips and a strained ligament, didn’t help matters, either.

In 1979, Page’s performance fell off further. His batting average plummeted to .247. He hit only nine home runs. With the emergence of a young Rickey Henderson in left field, Page began to play more and more as a designated hitter. The prospect of being a DH did not appeal to Page.

“If I can’t play in the outfield here,” Page told the Sporting News, “then I hope they release me next year.”

Paige did not get his wish. He was forced to play all of 1980 as a DH, while the A’s showcased one of the game’s best young outfields in Henderson, Dwayne Murphy and Armas. While Page hated being a DH, his hitting saw an upturn. He lifted his home run total to 17 and increased his OPS to a more respectable .754.

A bad slump at the start of the 1981 season resulted in Page heading back to the minor leagues, just before the players went out on strike.

As a result, Page continued to receive his pay during the players’ walkout. At the tail-end of the strike-interrupted season, he came back to play in three games for the A’s – all as a pinch-hitter. Page was still only 29, but the stardom he had flashed in 1977 seemed light years away.

In 1982, Page split his season between Oakland and Triple-A Tacoma. He then played all of ’83 with the A’s, but it was a disheartening year that saw him used only sporadically as a backup. In 1984, Page reported to camp with the A’s, but he would not last the entire Spring Training in Arizona. On March 29, the A’s released Page, bringing his seven-year tenure in Oakland to a close.

In May, Page drew some interest from his original team, the Pirates, who signed him to a minor league contract. After a tune-up at Triple-A Tacoma, where he batted .328, the Pirates brought him back to the big leagues in August. They used him as a pinch-hitter, a role in which Page excelled. In 15 plate appearances, he picked up three hits and collected three walks, giving him an on-base percentage of .417.

Page looked like he might have found a new role in which to prosper, but in reality, he was on the wrong side of 30 and playing for a Pirates team that was facing a rebuilding phase. In October, the Pirates released Page, though they did give him a non-roster invitation to Spring Training.

In 1985, Page played the entire season at Triple-A Hawaii, but posted mediocre numbers, convincing him that it was time to retire. At the age of 32, Page’s playing days had ended.

Page left baseball completely for a few years, but then returned to the game in the 1990s as a minor league hitting instructor with Tacoma. He also received an opportunity to appear in the baseball film, Angels in the Outfield, which hit theaters in 1994. The following year, the Kansas City Royals brought him back to the big leagues as their first base coach. And then in 2001, the St. Louis Cardinals promoted him to their major league staff as their hitting instructor. That’s where Page found his true niche.

In contrast to some old school hitting coaches, Page liked to work with videotape in helping Cardinals hitters break down their swings and correct any mechanical flaws. He also featured an outgoing personality, which allowed him to reach the young Cardinals’ hitters, most of whom had never seen him play. With his passionate approach to the art of hitting, Page became a favorite with the Cardinals’ players.

Page even became popular with Cardinals fans, some of whom praised him as the best hitting instructor the franchise had ever employed. Unfortunately, Page was also having problems with addiction. For years, he had been drinking heavily, and by 2004 the problem became acute.

That season, the Cardinals won 104 games on their way to reaching the World Series. Several Cardinals hitters enjoyed banner seasons under Page, including Albert Pujols, Scott Rolen, and Jim Edmonds. But Page clearly had a problem.

“I did work under the influence,” Page told St. Louis Today in 2005 in a story where Cardinals manager Tony La Russa was asked about a reporter smelling alcohol on Page’s breath.

After the World Series, a four-game sweep at the hands of the Boston Red Sox, La Russa sat down with Page and informed him that he was being fired.

Page accepted the blame, admitting in multiple interviews that “I screwed up.”

Realizing that his drinking had reached a critical stage, he entered himself into a rehabilitation facility. After completing the initial course of treatment, Page attempted to piece his life together. In 2006, he received an offer to become the hitting coach of the Washington Nationals. He accepted the offer, but the following year took a leave of absence for what he described as “personal problems.”

In 2010, Page returned to the Cardinals as a minor league hitting instructor, but the job lasted only through Spring Training. Still, Page appeared to have straightened out his life. H remained in touch with Cardinals coach Dave McKay, who saw Paige in the fall of 2010 and reported that he looked and felt good. According to McKay, Page had recently settled down and purchased a home. He was spending much of his time doing volunteer work for a local church.

Then on a Saturday night in March of 2011, Page settled into his bed for a night of sleep. He would never wake up. Passing away in the middle of the night, Page was just 59. To this day, no official cause of death has ever been established.

It’s hard to know exactly what happened that night. In addition to his struggles with alcoholism, Page had been a lifelong smoker. Perhaps his body simply gave out. We will probably never know for sure.

It was a sad ending, a life ended far too short, but perhaps we can take solace in knowing that Page seemed to find some peace near the end of his life. He also left behind a legacy as one of the game’s friendliest people.

Those who met him along the way – both during his days as a player and as a coach – universally praised Page for his outgoing manner, his willingness to talk and his accommodating nature.

Even as Page battled his demons, he still found a way to make others feel like they were more than worth his time.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame