- Home

- Our Stories

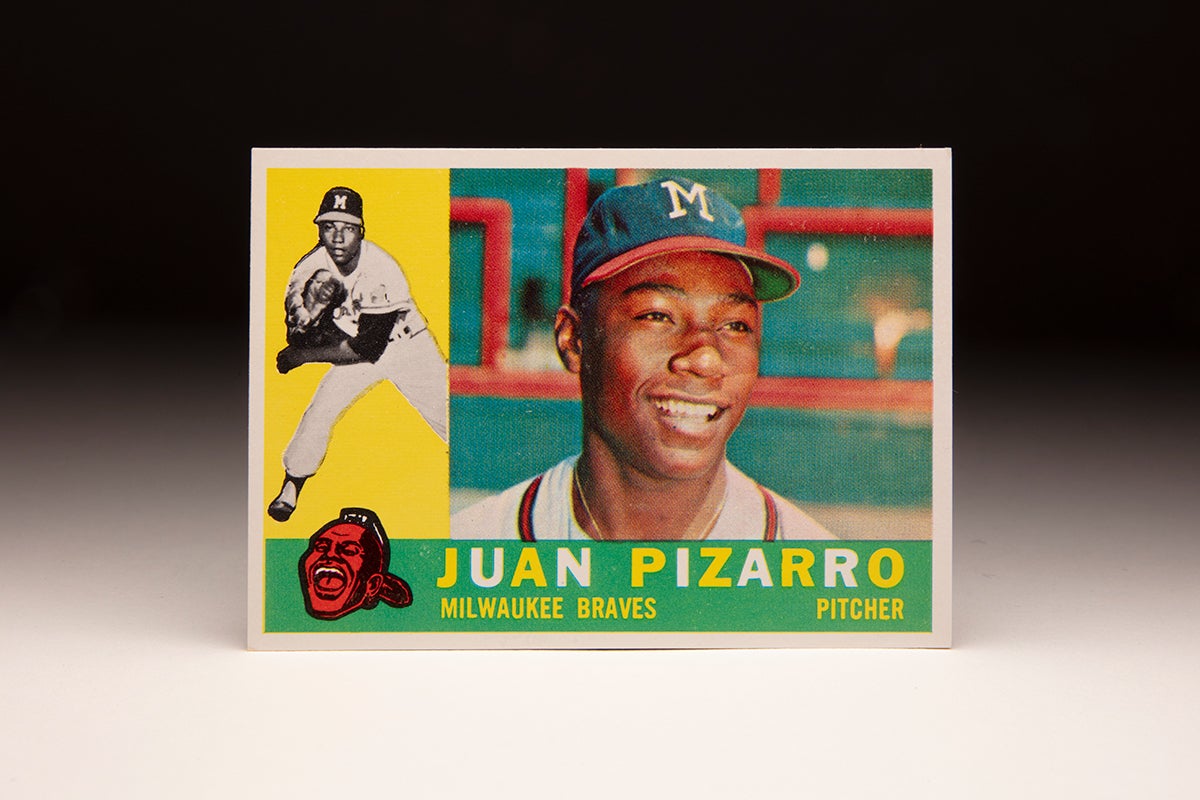

- #CardCorner: 1960 Topps Juan Pizarro

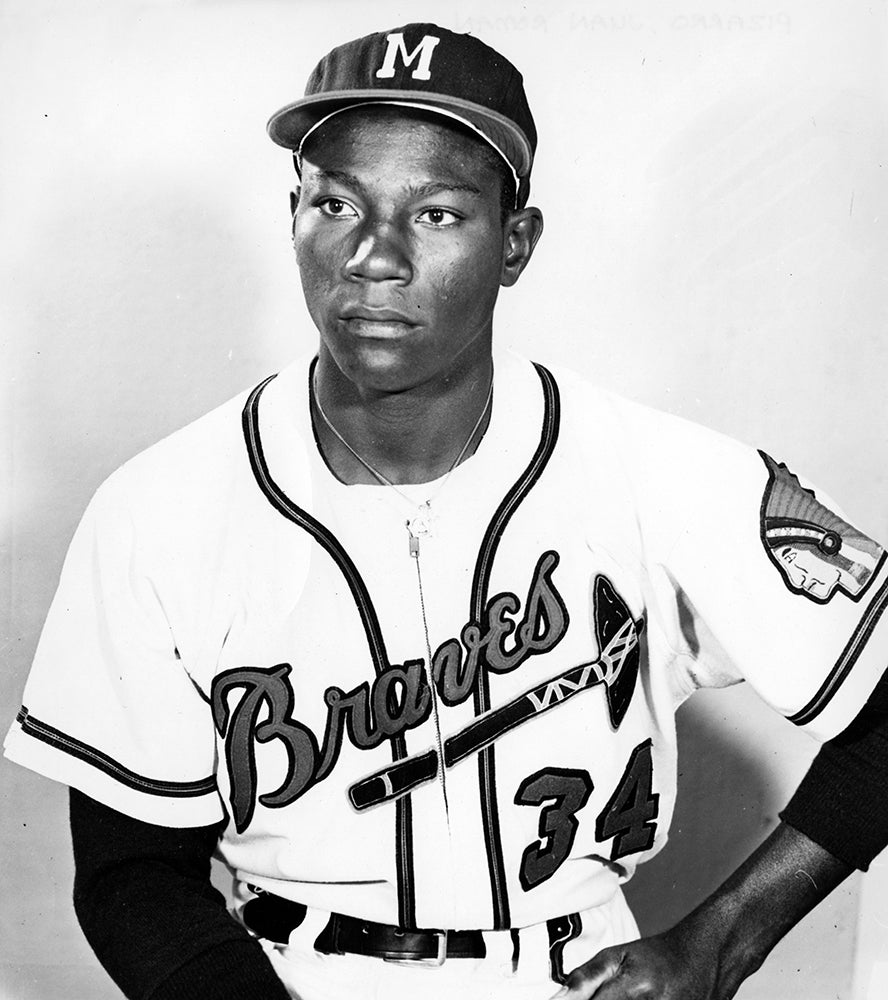

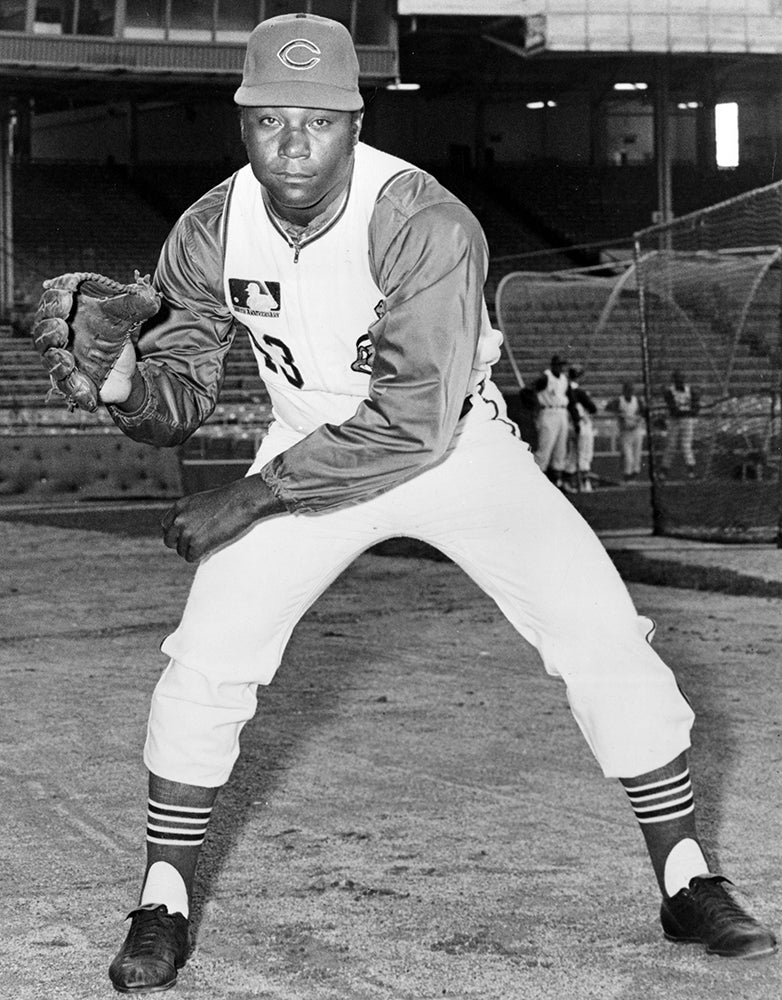

#CardCorner: 1960 Topps Juan Pizarro

He retired with the most wins of any big league pitcher born in Puerto Rico, and Juan Pizarro remains second on that list behind only Javier Vázquez.

And if not for a curious decision by the Milwaukee Braves in the late fall of 1960, Pizarro could have been the ace of a club that seemed destined to become a dynasty.

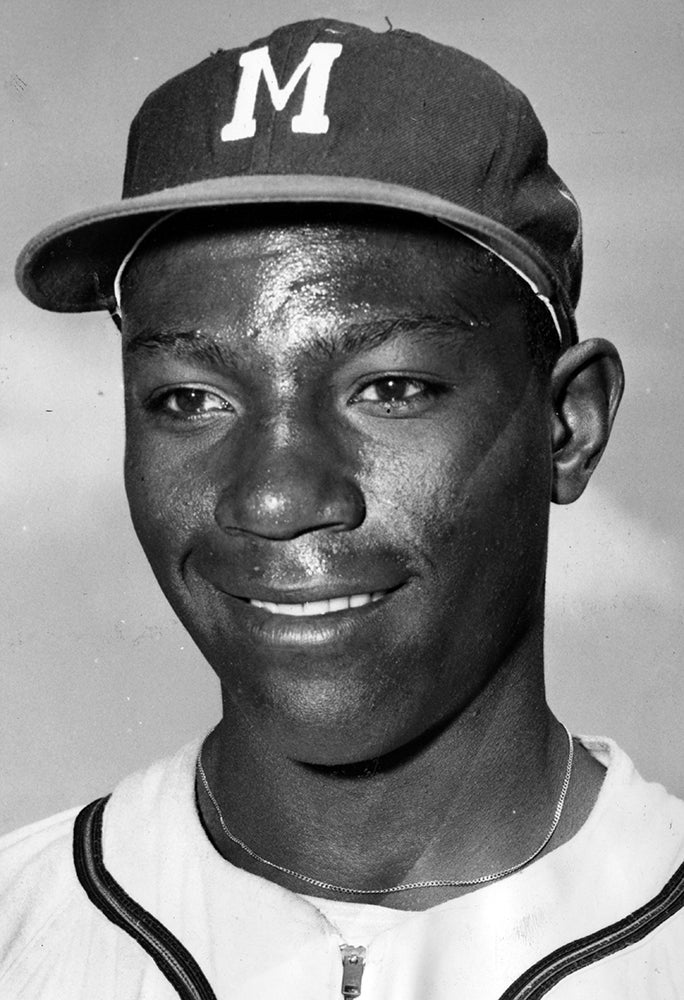

Born Feb. 7, 1937, in Santurce, Puerto Rico, Juan Ramon Pizarro was reported to be the “son of a chicken farmer” – according to a Canadian Press story from 1957. But Pizarro’s father actually trained birds for cockfighting, a sport that was legal in Puerto Rico until the end of the 2010s.

Pizarro came to baseball late, drawing the attention of Santurce Crabbers owner Pedrín Zorrilla – who had employed Pizarro as a batboy. When Pizarro finally joined his high school team, he dominated opponents with his smooth left-handed delivery. He had already acquired the nickname – Terín – that he would be known as for the rest of his life, a tag he acquired as a youngster when friends noticed his resemblance to Terry from the Terry and the Pirates comic strip.

Former big leaguer Luis Olmo, then a Braves scout, brought Pizarro to the attention of Milwaukee’s leading talent evaluators.

“Remarkable ballplayer,” Jacksonville Braves manager Ben Geraghty told the Charlotte News in 1956 when Pizarro was dominating the South Atlantic League as a 19-year-old rookie professional. “Milwaukee signed him after asking my advice. I was in the Winter League, Puerto Rico, and Luis Olmo had Pizarro lined up. I told (the Braves) to get him quick and that every dollar would be well spent. He’s got major league written all over him.”

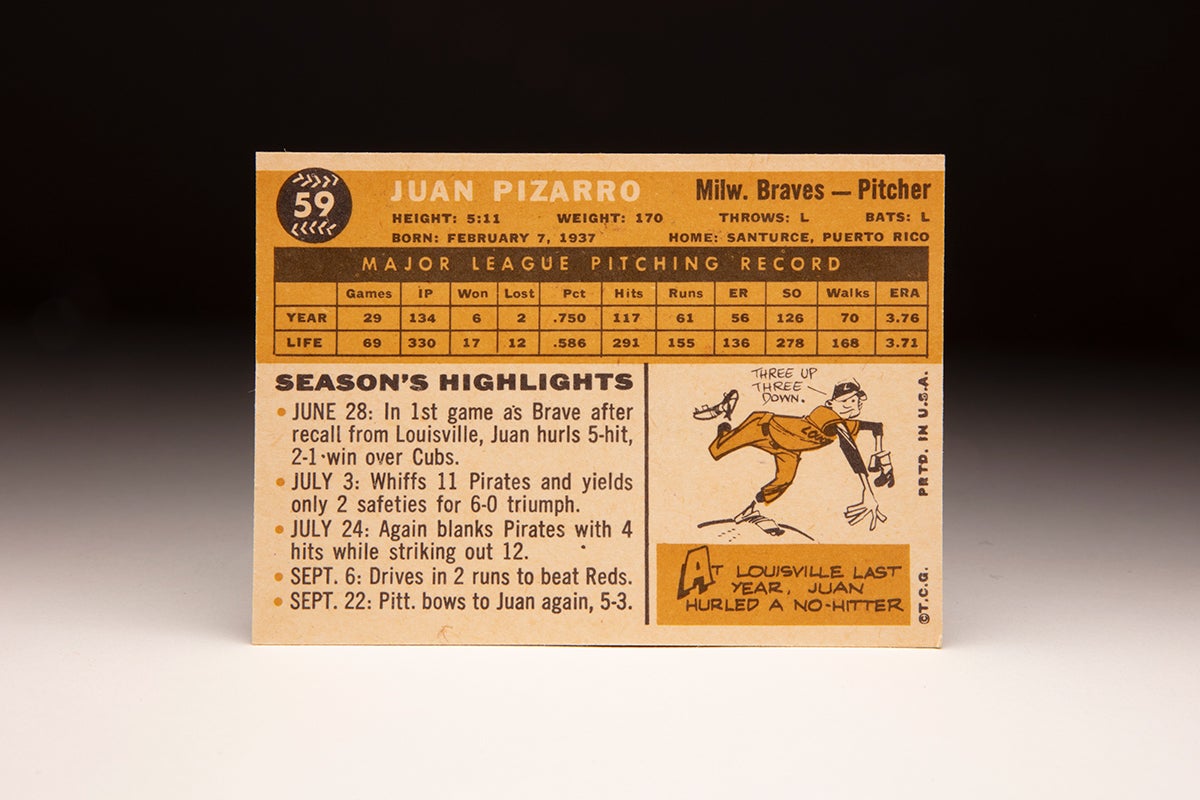

Pizarro signed with the Braves prior to the 1956 season in a deal that was widely reported to be worth $30,000. But Zorrilla reportedly received most of that money. The Braves, meanwhile, assigned Pizarro to the South Atlantic League, where he went 23-6 with a 1.77 ERA while striking out 318 batters over 274 innings.

“I’d say there are faster pitchers, even in this league,” Geraghty told the United Press during the 1956 season. “But his ball really moves. Too many good hitters in this league are swinging and missing. His ball is alive and that is what’s going to make him a great big leaguer.”

Pizarro became one of the game’s top prospects during the 1956 campaign, and the Braves invited him to their Spring Training camp in Bradenton, Fla., in 1957. He immediately became the talk of the town.

“He’s as fast as anyone who ever threw a baseball,” Hall of Famer Bill Terry, the president of the South Atlantic League, told the Newspaper Enterprise Association. “I don’t know (Cleveland fastball phenom Herb) Score that well, but I do know that Pizarro pitches with much less effort. He’s as loose as Hal Newhouser was at his best.

“He’s as natural a pitcher as Henry Aaron is a hitter.”

The Braves kept Pizarro on the big league roster to start the 1957 season but brought him along slowly. He made his debut on May 4 against Pittsburgh, allowing just one run over seven innings in a hard-luck 1-0 defeat. He remained in the rotation for the next six weeks but was sent to the bullpen in late June with a 3-5 record and 3.96 ERA.

The Braves then shipped Pizarro to Triple-A Wichita for most of July, where he went 4-0 with a 4.25 ERA in five starts. He returned to Milwaukee in August and worked as a swingman for the rest of the year, finishing with a 5-6 record and 4.62 ERA over 99.1 innings. The Braves won the National League pennant by eight games over the Cardinals, and Pizarro pitched a scoreless inning of relief in the team’s last game of the season, securing his spot on the World Series roster.

Though he appeared in just one game in the 1957 World Series against the Yankees – relieving starter Bob Buhl in the first inning of Game 3 and allowing two runs over 1.2 innings – Pizarro walked away with a ring when the Braves defeated New York in seven games.

Expected by many to secure a permanent place in the Braves’ rotation in 1958, Pizarro struggled in Spring Training after dominating the Puerto Rican Winter League with Caguas. He went 14-5 with a 1.32 ERA over 170 innings that winter, a taxing workload for a pitcher who turned 21 right before reporting to camp in Bradenton.

“Pizarro’s chief trouble is control,” Braves manager Fred Haney told the Associated Press. “It’s possible winter ball hurt him. He did a lot of work there, then laid off a little while before coming here.”

Despite the five-figure deal the Braves paid for Pizarro’s contract, the pitcher was not subject to the bonus baby rules of the time – which would have mandated Pizarro remain in the big leagues – because almost all of the money went to Pedrin Zorrilla. MLB executives like Cardinals general manager Frank Lane complained publicly that Pizarro should not be allowed to go to the minors but the Braves won the argument and sent Pizarro to Wichita to start the 1958 season.

Thus began a two-year odyssey where Pizarro shuttled between Milwaukee and Triple-A. He went 9-10 with Wichita before being recalled to the Braves in late July of 1958, helping Milwaukee win another NL pennant while going 6-4 with a 2.70 ERA in 96.2 innings. Once again, Pizarro appeared in one World Series game – this time allowing one run over 1.2 innings of relief in Game 5 in a contest the Braves lost 7-0. The Yankees rallied from a 3-games-to-1 deficit to win the title.

Pizarro made the Opening Day roster in 1959 but worked mostly out of the bullpen before being sent to Triple-A Louisville in June. He went 4-1 with a 1.07 ERA in five starts for the Colonels, including a no-hitter against Charleston on June 16 that was documented in newspapers around the country thanks to a write-up by United Press International.

Pizarro went 6-2 with a 3.77 ERA with the Braves that year over 133.2 innings, striking out 126 batters. The Braves and Dodgers finished in a dead heat at 86-68 in the National League standings, necessitating a best-of-3 playoff that Los Angeles won in two games. Pizarro did not pitch in either game.

In 1960, Charlie Dressen took over as the Braves manager and inserted Pizarro into the starting rotation – telling anyone who would listen that Pizarro was the best left-handed pitching prospect in the National League. But Pizarro battled a sore arm during the year over 114.2 innings, going 6-7 with a 4.55 ERA.

“I told him to go out there and just throw overhand – none of that sidearm stuff,” Dressen told the AP earlier in the 1960 season. “When he pitches like that, there isn’t anybody who is going to hit him.”

But after four seasons, the Braves decided it was time to move on. On Dec. 15, Milwaukee sent Pizarro and fellow young pitcher Joey Jay to the Reds in exchange for Roy McMillan, who was expected to replace veteran Johnny Logan at shortstop. The Reds then immediately packaged Pizarro and pitcher Cal McLish and sent them to the White Sox in exchange for third baseman Gene Freese.

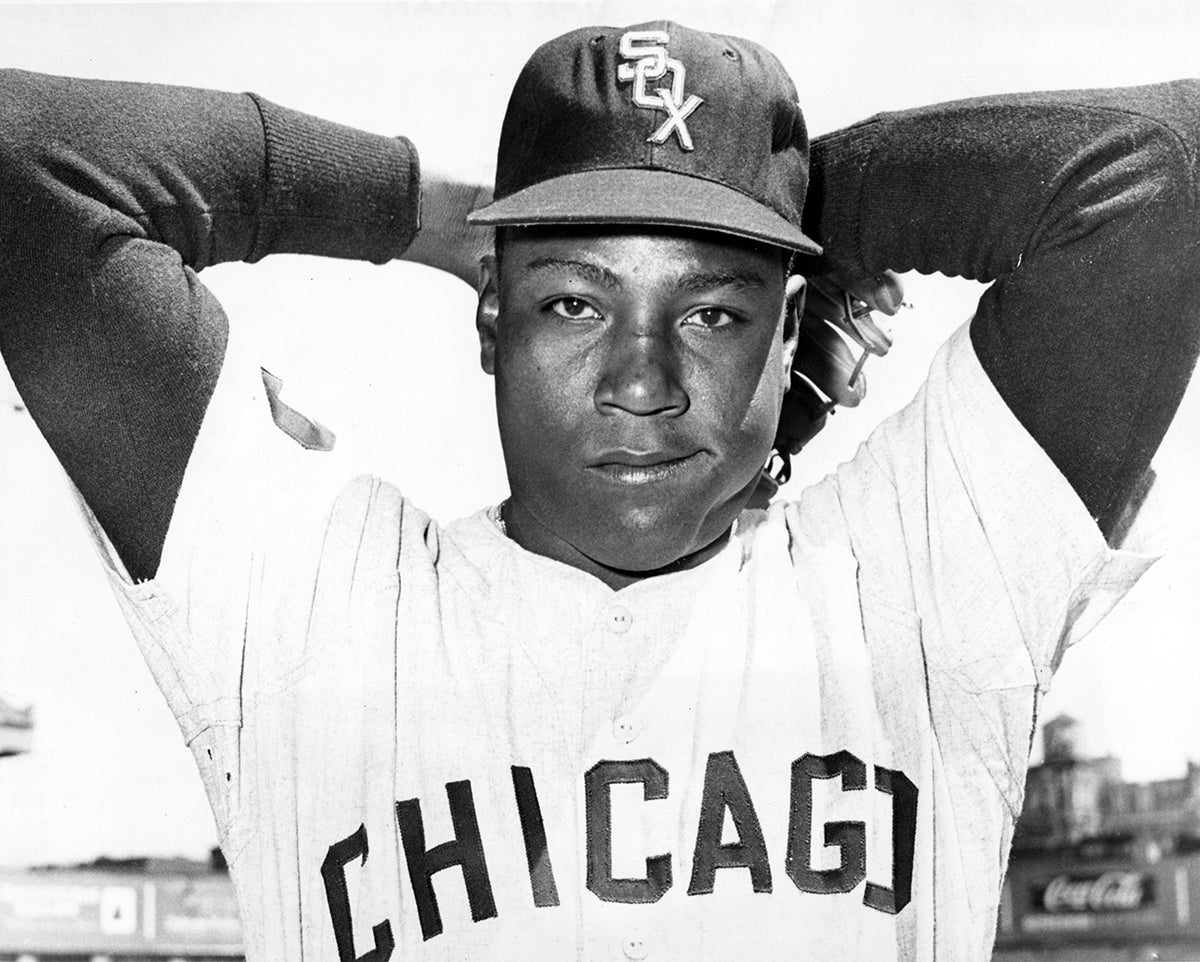

“The addition of Pizarro and McLish will give the staff a boost,” White Sox owner Bill Veeck told the AP after the deals.

The trades powered the Reds to the 1961 NL pennant as Jay won 21 games and Freese drove in 87 runs. And Pizarro found a home with the White Sox.

The Braves, meanwhile, parted with two pitchers who combined for 121 wins from 1961-64 in exchange for McMillan, who hit .237 over three seasons as a regular from 1961-63. And after winning two NL pennants and tying for another from 1957-59, the Braves did not advance to the postseason again until 1969.

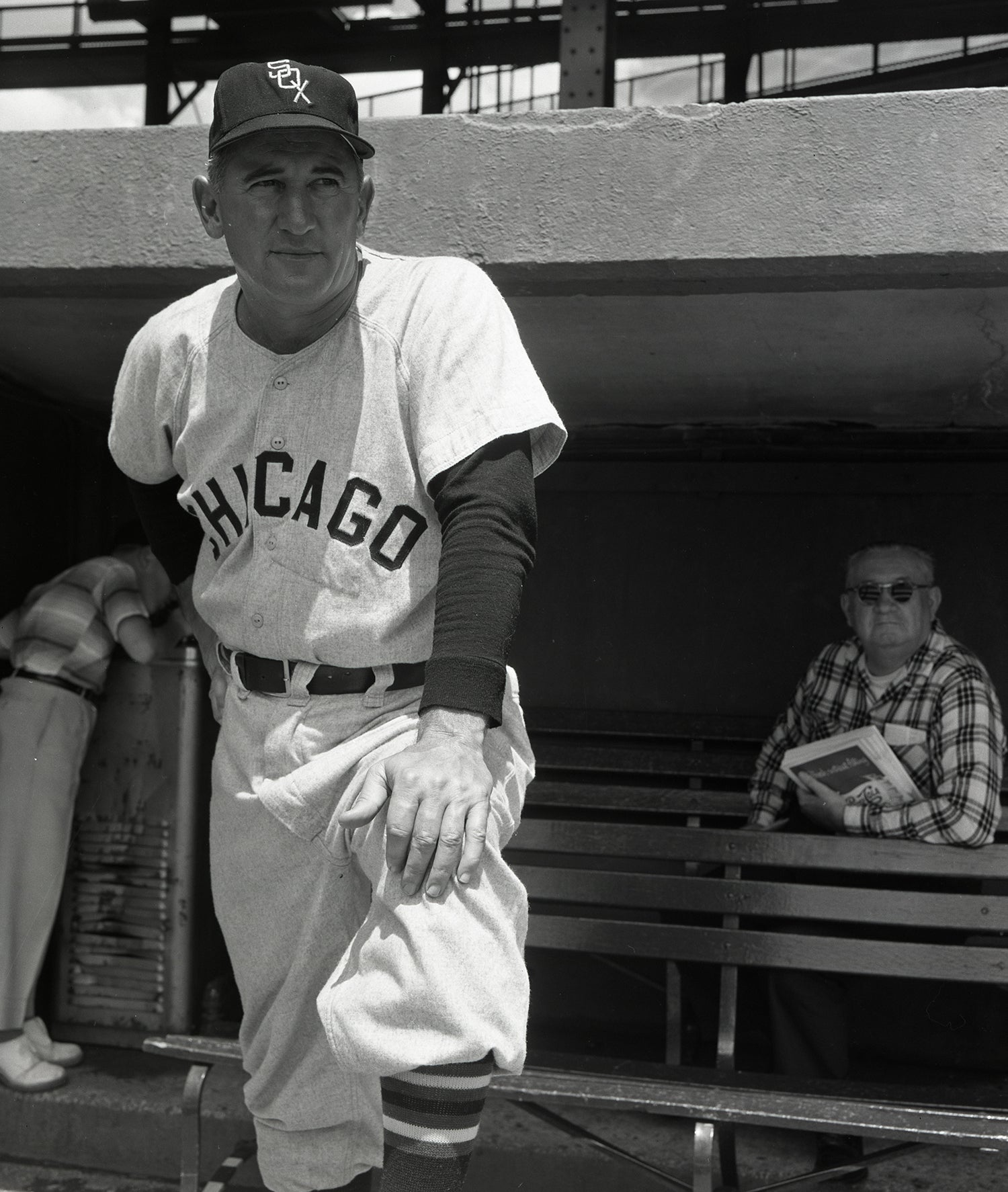

White Sox manager Al López put Pizarro in the bullpen to start the 1961 season – believing that regular work would help Pizarro’s approach to the game.

“Pizarro had lost his confidence,” López told the Newspaper Enterprise Association. “Juan got behind hitters, had to lay the ball in there and was belted rather merrily in the spring. Meanwhile, (pitching coach) Ray Berres had Pizarro working in his delivery. Juan was rushing forward too fast – his body forward, his arm back. He had to be taught to relax and shelve odd pitches he had acquired.”

In June, López felt Pizarro was ready to return to the rotation. He tossed four complete games in his first 10 starts, fanned 59 batters in six starts in August and finished the season with a 14-7 record, a 3.05 ERA and 188 strikeouts in 194.2 innings even though he didn’t notch his first win until June 13.

“With that arm, he’s going to be truly great,” López told NEA. “His (fastball) jumps in different directions and he has improved his curve and slider along with his control.”

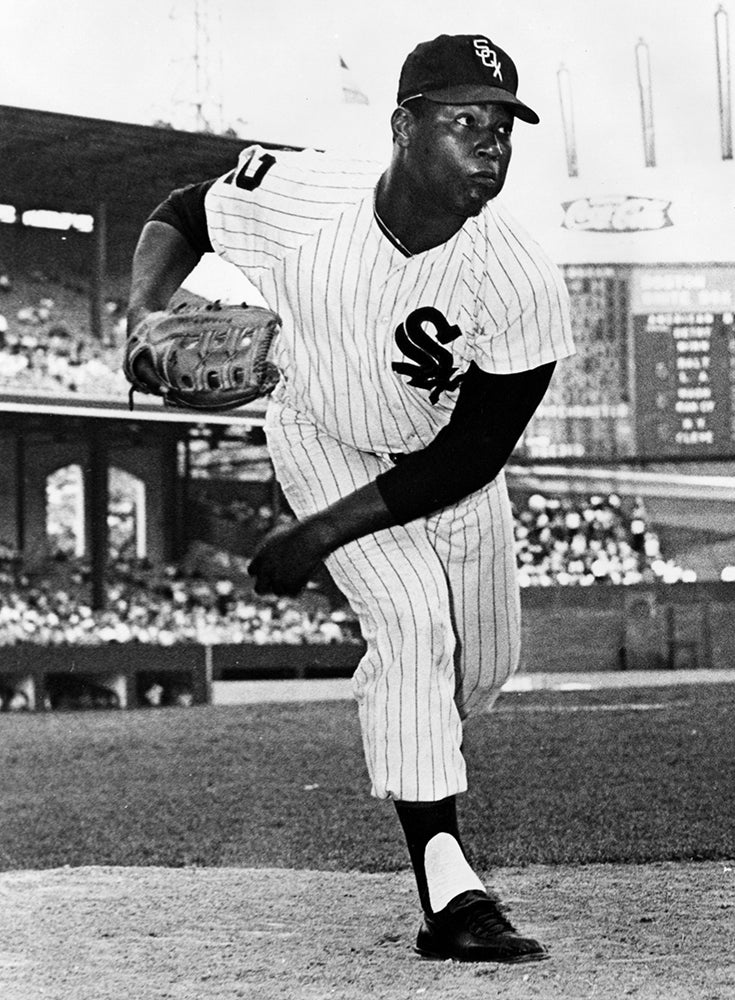

Pizarro’s numbers slipped to 12-14 with a 3.81 ERA in 1962 but he still struck out 173 batters over 203.1 innings and was the White Sox’s Opening Day starter. But in 1963 and 1964, Pizarro established himself as one of the American League’s best pitchers.

Pizarro went 16-8 with a 2.39 ERA and 163 strikeouts in 214.2 innings in 1963, earning his first All-Star Game selection and pitching a scoreless inning in the Midsummer Classic. The next season, he was even better – going 19-9 with a 2.56 ERA and 162 strikeouts in 239 innings and earning another All-Star Game berth.

At 27, Pizarro appeared to be entering his prime. But the 1964 season would mark the last time he was a regular starter, the last time he struck out more than 100 batters in one season and the final time he would post a double-digit win total.

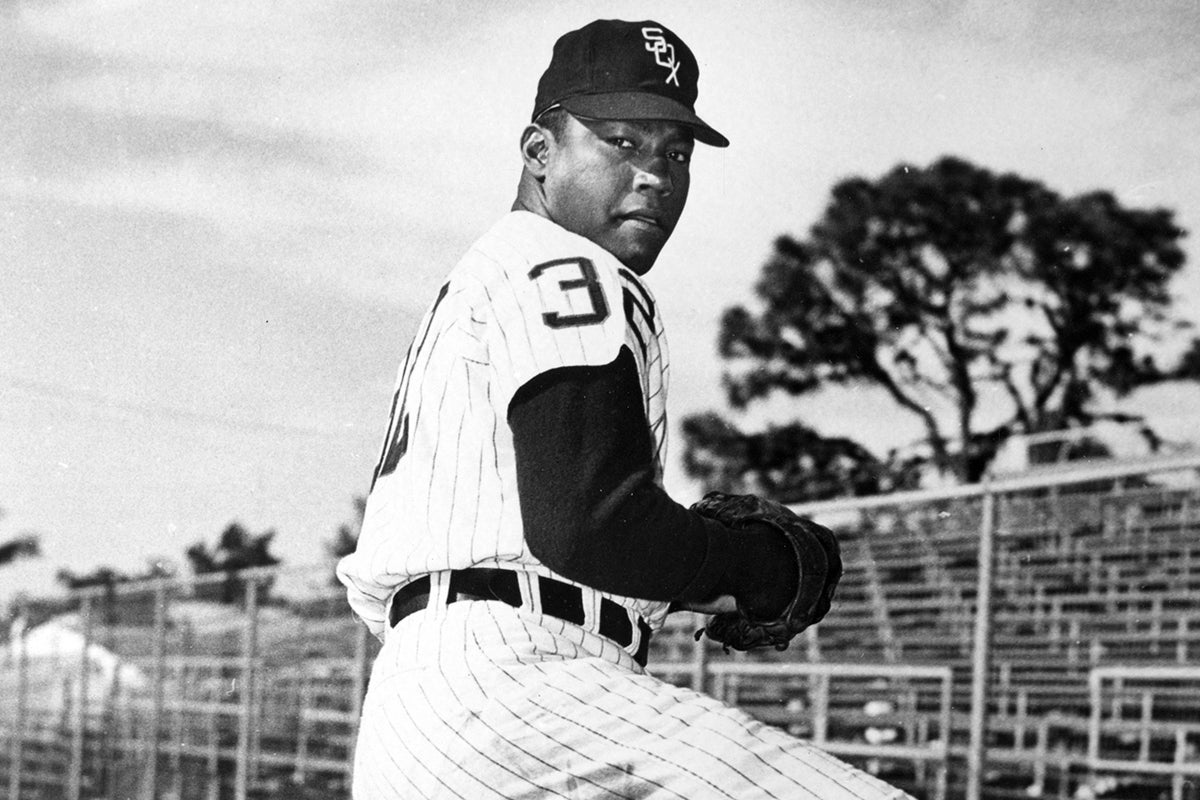

Pizarro held out to start the 1965 season, eventually agreeing to a contract worth a reported $30,000 on April 2. After making just seven starts in the first three months of the campaign, Pizarro was diagnosed with a torn triceps tendon in his left arm and was sidelined for a month. He returned to make 10 effective starts in August and September, finishing the season with a 6-3 record and 3.43 ERA in 97 innings.

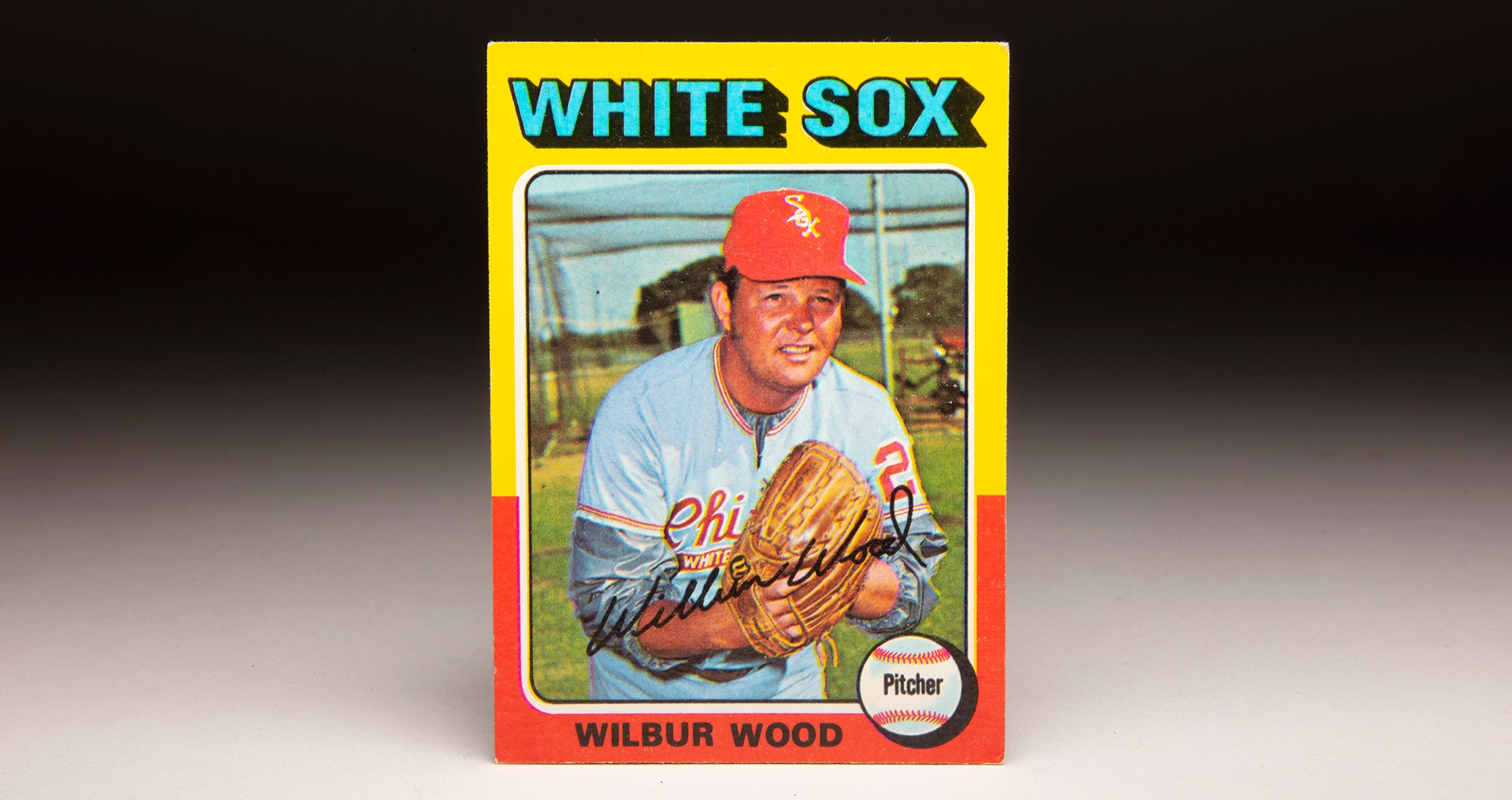

Pizarro assumed a swingman role in 1966, going 8-6 with a 3.76 ERA and three saves in 88.2 innings over 34 games. Then on Nov. 28, the White Sox sent Pizarro to the Pirates to complete an October trade that brought Wilbur Wood to Chicago.

The deal was reported in some circles to be a cash transaction worth $30,000. Either way, the Pirates figured they’d take a chance on the former two-time All-Star who had worn out his welcome in Chicago after feuding with manager Eddie Stanky.

“We’re not expecting any miracles from (Pizarro),” Pirates general manager Joe Brown told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “If we get, say, 12 wins out of him, we’d be most happy. Then again, Pizarro is the type of pitcher who might just win real big in new surroundings.”

But after starting the season in the rotation and throwing a four-hit shutout against the Cardinals on April 30, Pizarro began to struggle and was moved to the bullpen in June. He went 8-10 with a 3.95 ERA over 50 games and made 12 appearances out of Pittsburgh’s bullpen in 1968 before his contract was sold to the defending AL champion Red Sox on June 27.

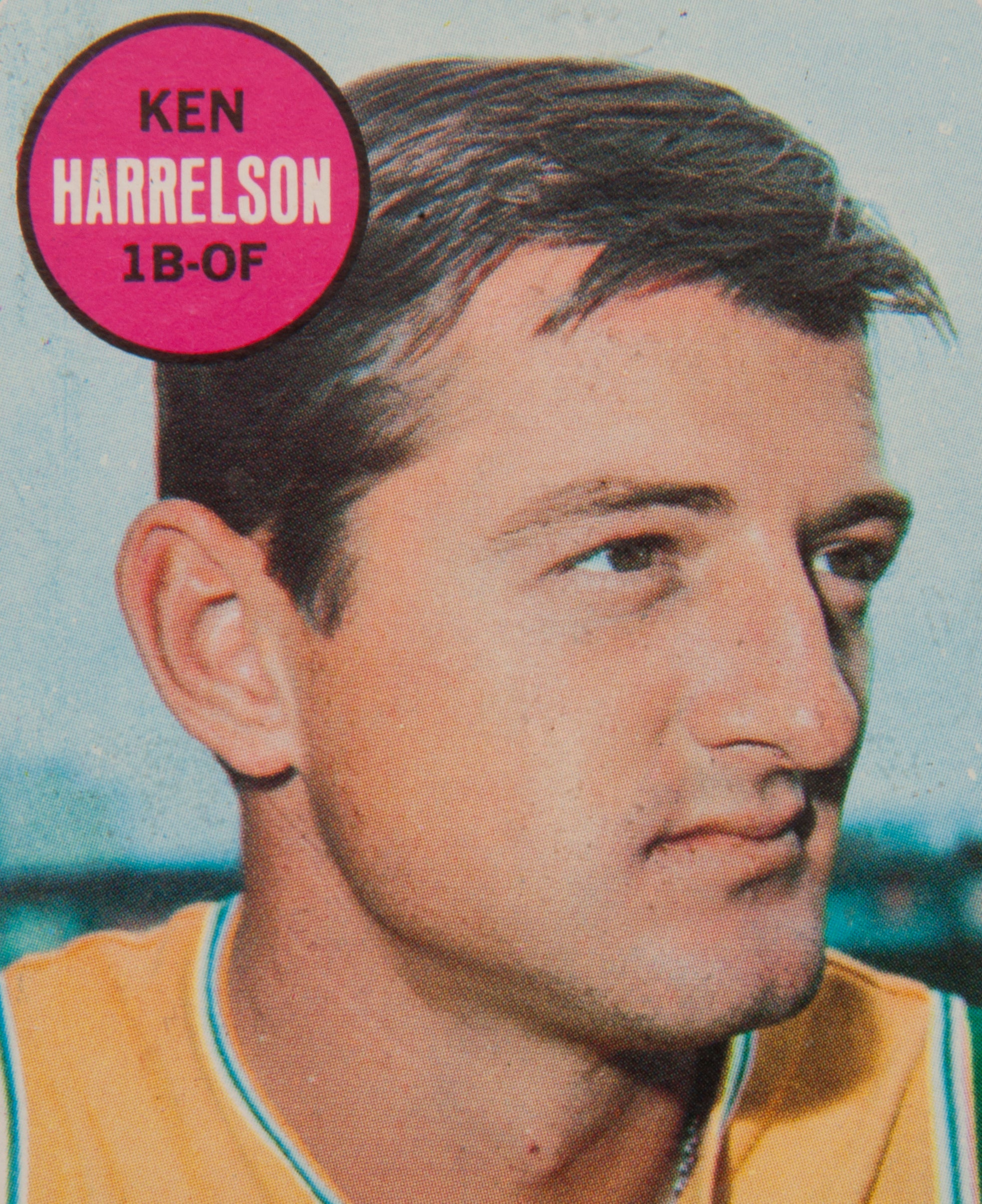

Pizarro went 6-8 in 19 games – including 12 starts – for Boston that year, pitched in six games out of the bullpen for the Red Sox in 1969 and then was sent with Ken Harrelson and Dick Ellsworth to Cleveland on April 19 in exchange for Joe Azcue, Vicente Romo and Sonny Siebert. The trade made headlines when Harrelson initially refused to report. Pizarro, meanwhile, had already been placed on waivers by the Red Sox and was considered a minor part of the deal.

But while Harrelson hit just .222 (albeit with 27 home runs and 95 walks) with Cleveland after reporting, Pizarro pitched well – working 48 games and going 3-3 with a 3.16 ERA and four saves. On Sept. 21, 1969, Pizarro’s contract was purchased by the Athletics and he pitched three games for the A’s down the stretch.

Oakland released Pizarro on May 15, 1970, and he hooked on with the Angels, going 9-0 with a 3.24 ERA for Triple-A Hawaii before being traded to the Cubs. He appeared in 12 games with Chicago toward the end of the season, then went 9-6 with the Cubs’ Triple-A affiliate in Tacoma before returning to the big leagues. Over 14 starts in the second half of the season, Pizarro had his final sustained MLB success – pitching six complete games, including three shutouts and a one-hitter against the Padres on Aug. 5.

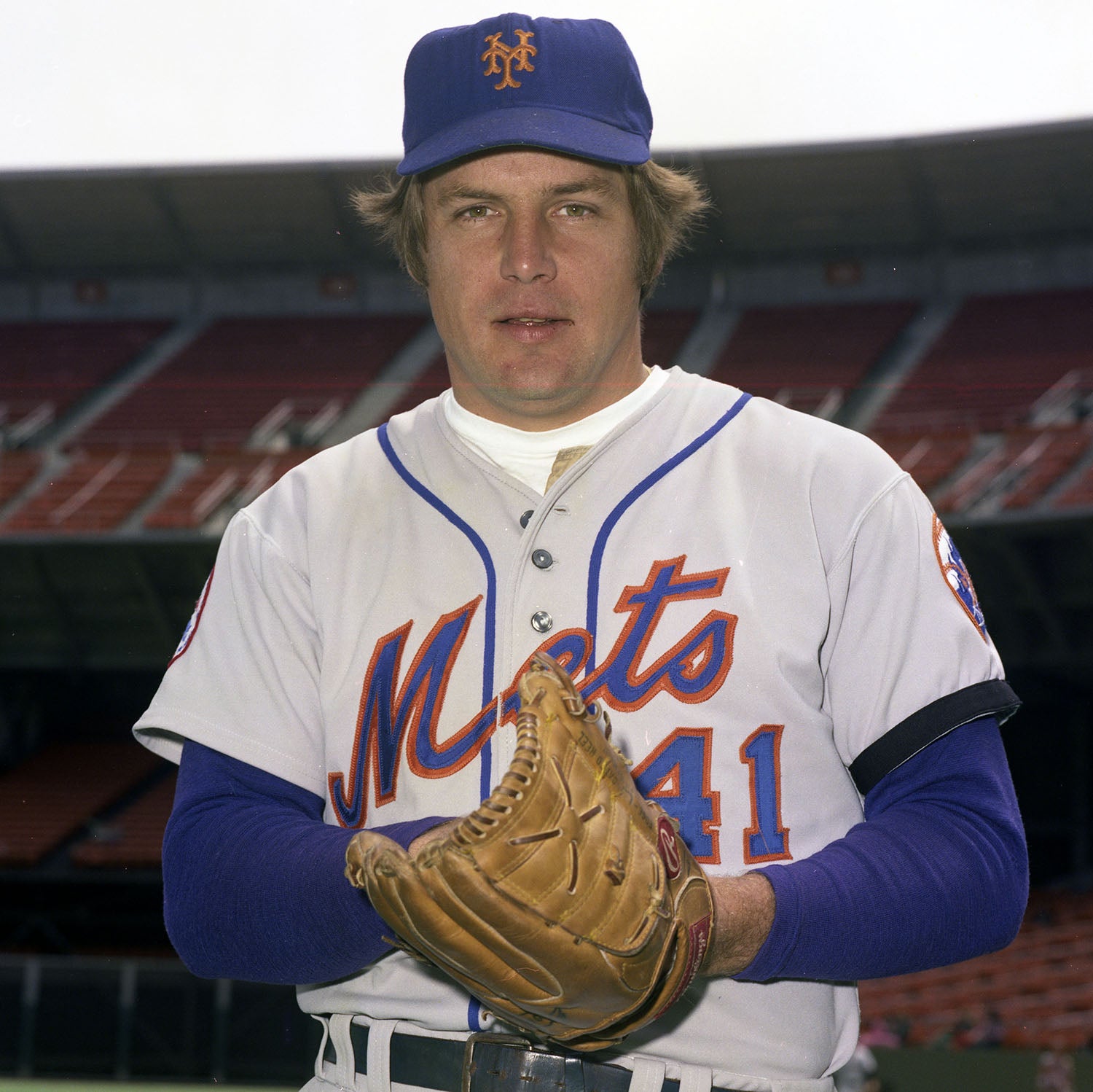

In his six-hit shutout against the Mets on Sept. 16, Pizarro homered off Tom Seaver for the game’s only run. He was the sixth pitcher in history to hit a home run in a 1-0 shutout win.

He finished the season with a 7-6 record and a 3.46 ERA but was unable to duplicate that success in 1972, going 4-5 with a 3.94 ERA in 16 games while battling injuries.

In 1973, he began the year with Triple-A Wichita, made it up to Chicago for two games and then had his contract sold to Houston. He pitched in 15 games for the Astros, was released by Houston on April 9, 1974, and then – after going 13-6 with a 1.57 ERA and nine shutouts for Cordoba of the Mexican League – signed with the Pirates on Aug. 20. He made seven appearances for Pittsburgh, including two late-season starts as the Pirates chased the NL East title. On Sept. 26 vs. the Mets, Pizarro worked eight innings, allowing two runs in an 11-5 win that pulled Pittsburgh into a tie with the Cardinals atop the division with six games remaining.

Pizarro would not work in any of those final six games – but the Pirates won the division by a game-and-a-half over St. Louis.

With a 1-1 record and 1.88 ERA in seven games for Pittsburgh, Pizarro was placed on the National League Championship Series roster vs. the Dodgers. Pizarro worked a scoreless two-thirds of an inning in Game 4 as the Dodgers clinched the pennant that day with a 12-1 victory. It would be Pizarro’s last outing in the majors.

On Oct. 24, the Pirates outrighted Pizarro to their Triple-A affiliate in Charleston, W.Va. They brought Pizarro to Spring Training in 1975 but sent him to the minors on March 26, and Pizarro opted to return to the Mexican League. He went 14-7 with a 1.98 ERA for Cordoba in 1975 and followed that with 11 wins and a 2.64 ERA in 1976 before ending his career.

Pizarro later worked for the Puerto Rican government in a program that taught baseball to children and even coached in the minor leagues. He passed away on Feb. 18, 2021.

Over 488 big league games, Pizarro was 131-105 with a 3.43 ERA and 1,522 strikeouts in 2,034.1 innings. His peak was a short four seasons – but they were four seasons that might have been championship campaigns had they been spent with Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews in Milwaukee.

“While he may not be as swift as Walter Johnson, Dazzy Vance, (Lefty) Grove, Van Lingle Mungo, Bob Feller and other genuine fireballers,” White Sox manager Al López said of Pizarro in 1961, “he can overpower the best of hitters.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum