- Home

- Our Stories

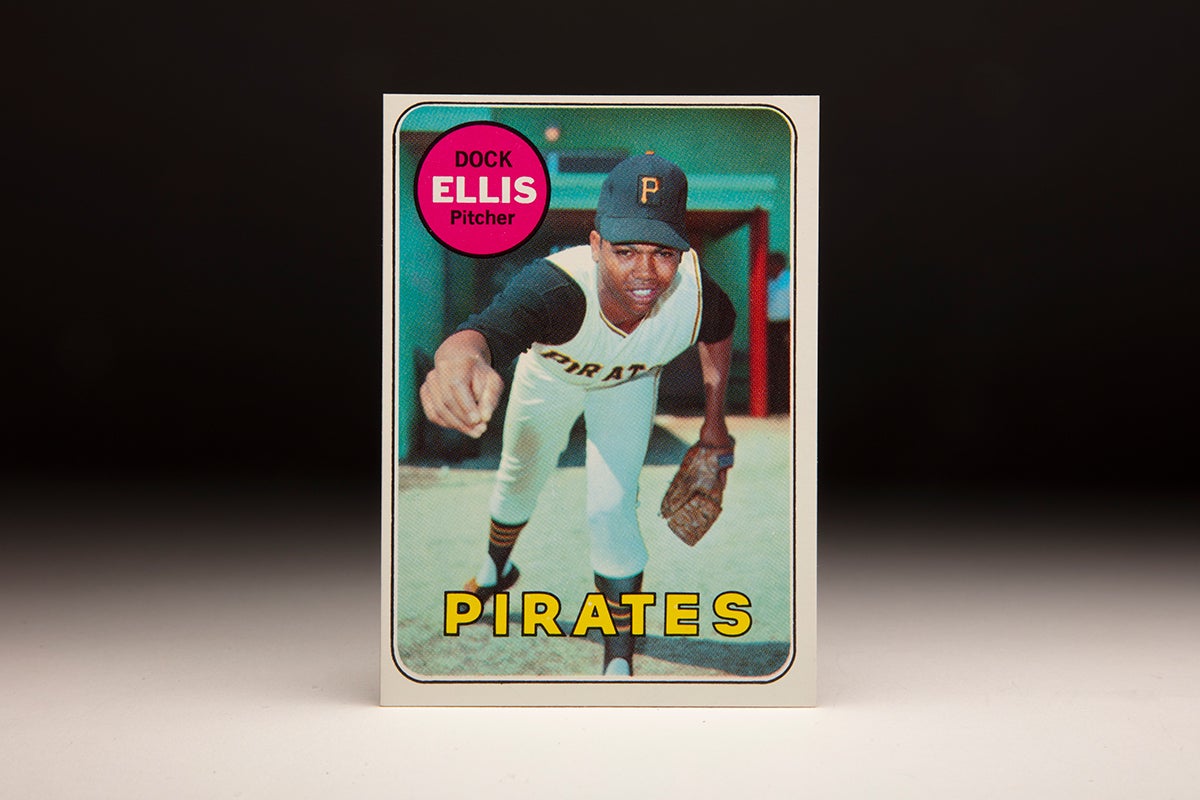

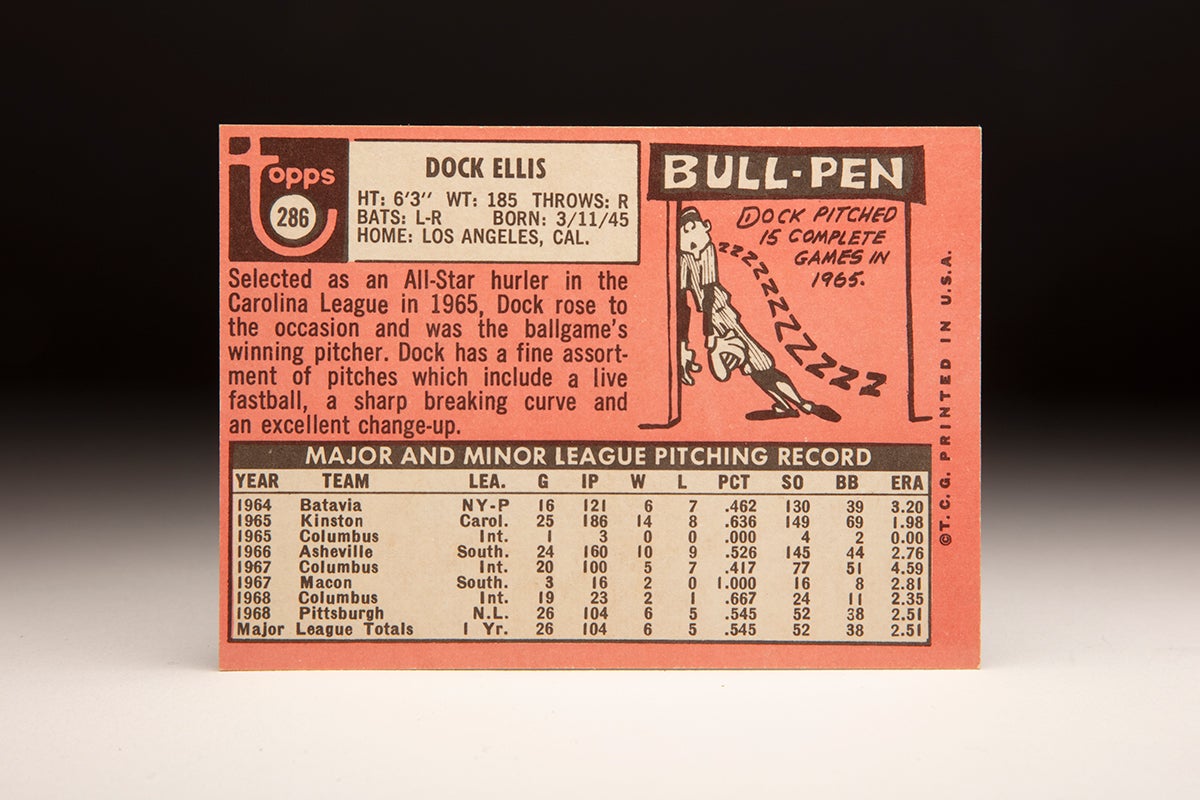

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Dock Ellis

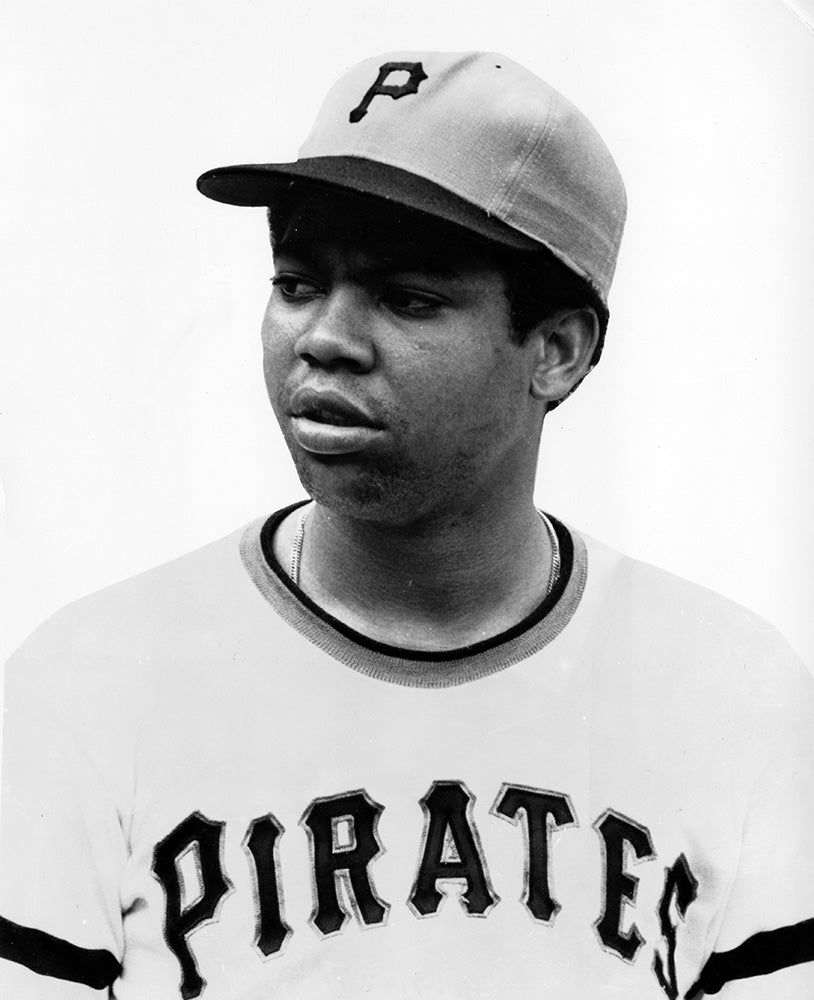

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Dock Ellis

The off-the-field stories about Dock Ellis often overshadow a career where the talented right-hander emerged as one of the best pitchers in baseball.

And while his journey ended in 2008 with his passing at the relatively young age of 63, Ellis’ numbers remain a testament to his talent and desire to succeed.

Born March 11, 1945, in Los Angeles, Dock Phillip Ellis grew up in the Watts neighborhood and starred in basketball and track at Gardena High School, appearing regularly in local newspaper stories in the early 1960s. He played baseball as a sidelight until joining the high school team as a senior, leading the Mohicans to a league championship.

“I guess you’d say basketball really was my sport then,” Ellis told The Daily Breeze of Torrance, Calif., in 1970. “I had some good offers to go to college. UCLA and USC were among the schools showing interest in me.”

But minor brushes with the law and school officials put Ellis’ athletic career in jeopardy.

“My vice principal put it on the line for me one day,” Ellis told The Daily Breeze. “About seven or eight universities had written the school about me. He took the letters and threw them all into a trash can. Then he marched me into his office and showed me my grades. I couldn’t fulfill any entrance requirements because I had no grades. I wasn’t going anywhere except to Harbor JC.”

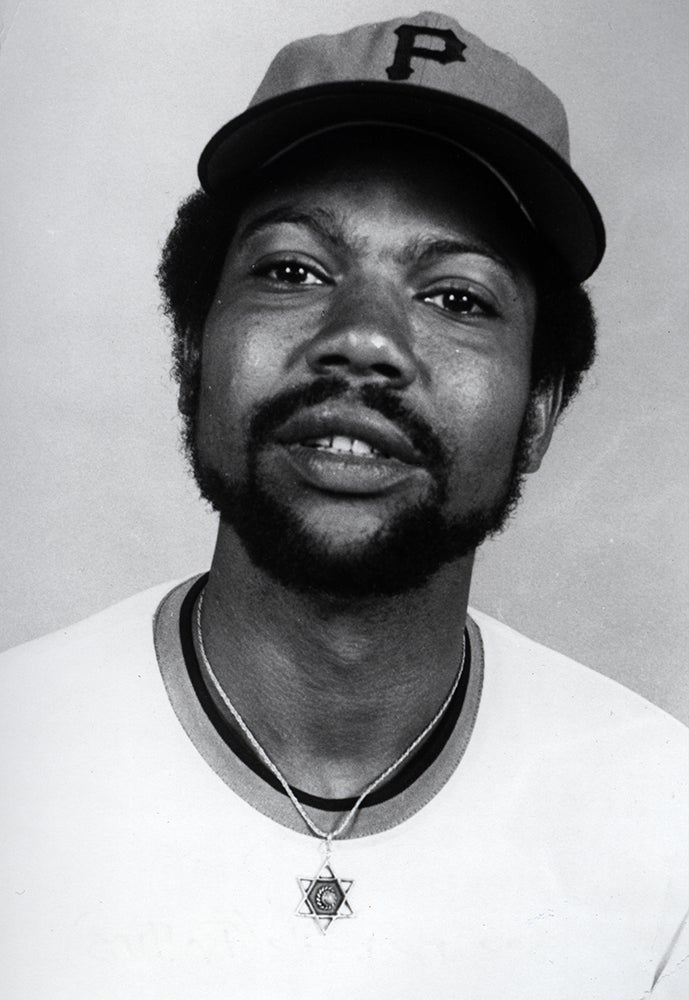

Ellis enrolled at what is now Los Angeles Harbor College but lasted only one semester before signing an amateur contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates on Jan. 14, 1964 – a year before the creation of the MLB Draft. Ellis seemed to be in line for a substantial signing bonus but received little money after being arrested for automobile theft.

“I almost went to jail for grand theft auto,” Ellis told The Daily Breeze. “I was always getting in trouble.”

With the help of his future father-in-law, who was a lawyer, Ellis was able to convince authorities to let him report to the Pirates’ New York-Penn League team in Batavia, N.Y., for the 1964 season. He went 6-7 with a 3.20 ERA, showing off his live right arm by striking out 130 batters over 121 innings.

But it was in Batavia that Ellis’ substance abuse problems began to get serious.

Ellis ordered a beer in a restaurant “just to show everyone I could pass for 21 (years of age),” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times in 1985 when he was pitching in an old-timers league.

After being told the legal drinking age in New York was 19 – which Ellis had reached that March – he said: “OK, take the beer back and bring me some vodka stingers. That was the opening for me to really get into drinking. (And) it just kept progressing. Marijuana and pills were all over the place. LSD (too).”

But Ellis’ talent kept him moving through the Pirates’ system. He went 14-8 with a 1.98 ERA for Class A Kinston of the Carolina League in 1965 and then was 10-9 with 145 strikeouts over 160 innings for Double-A Asheville in 1966.

All the time, Ellis was taking amphetamines.

“I was into the speed in the minor leagues because of the expectations put on me by management and by myself to hurry up and get to the big leagues,” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times. “So how did I deal with the stress? I medicated with the drugs. If I’m high, I’m not afraid of anything.”

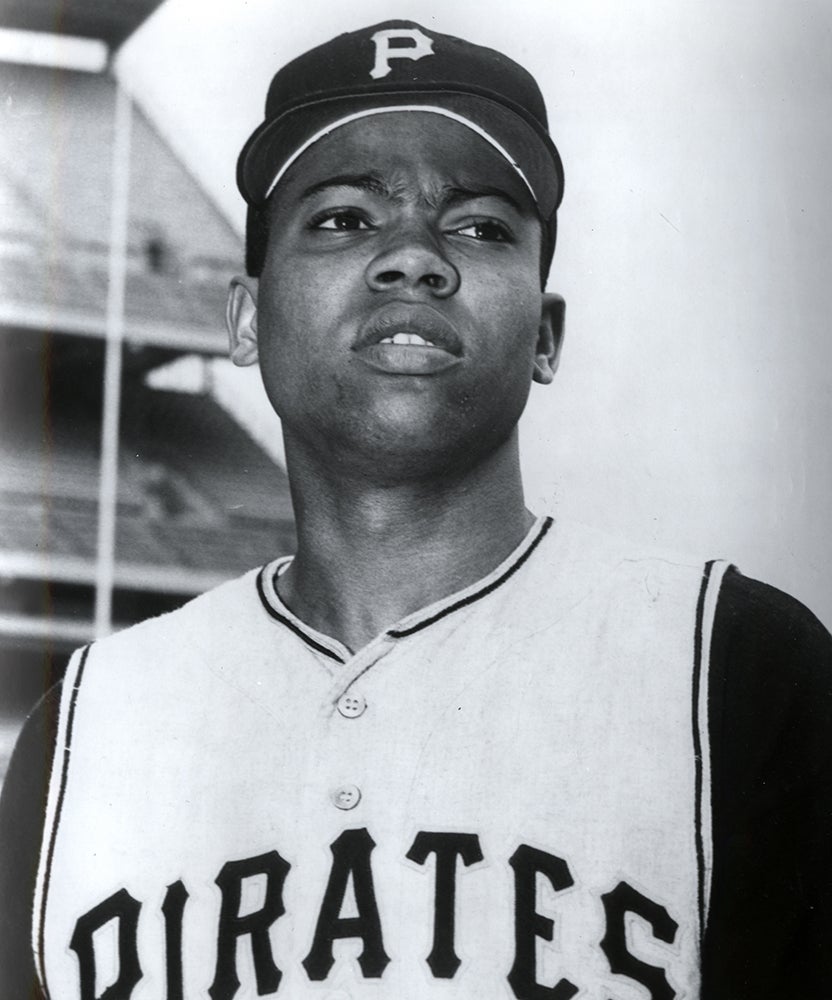

Ellis made it to Triple-A in 1967 and then began the 1968 season at the same level, staging a contract holdout before he had pitched in a big league game. He finally agreed to a deal and reported to Columbus before debuting with the Pirates in June. He would go 6-5 that year with Pittsburgh, posting a 2.50 ERA while working as a starter and reliever.

The next spring, Ellis earned a spot in the Pirates’ rotation and started the team’s third game of the season. He went 11-17 with a 3.58 ERA for a Pittsburgh team that finished 88-74 but featured an unsettled clubhouse – with several pitchers, including Ellis and Bob Veale, unhappy that manager Larry Shepard employed a five-man rotation, an unusual arrangement in that era.

Shepard did not last the season, and Danny Murtaugh returned to manage the team in 1970. It would mark the beginning of a successful era for the team and Ellis.

In 1970, Ellis started Pittsburgh’s second game of the season and struck out 13 Mets – which turned out to be a career-high – in a 2-1 victory. Then on June 12, Ellis became part of baseball lore when he pitched a no-hitter against the Padres. He walked eight batters in the game – an unsurprising total when it became known that Ellis was high on LSD during the contest.

“That wasn’t something that was done to say: ‘I’m gonna take some acid and pitch,’” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times. “I drove to L.A. (the Pirates had an off day between a June 10 game in San Francisco and the June 12 game in San Diego; Ellis received permission not to travel with the team), got loaded, tripped on acid two or three times. I lost a day. It’s Friday and I’m thinking it’s Thursday. The girl (he was with) says ‘Dock, you’re pitching today.’ I took the acid at (noon). She told me at 2. I caught the plane at 3. I got to the stadium around 4:30. The game was at 6:05. I took some greenies (Dexamyl) and bennies (Benzedrine) because it was a habit. It was natural to take the stuff, forgetting that I had taken the acid. So I was way out there.”

Ellis said he never again took LSD during the season but “I never pitched a game in the major leagues when I wasn’t high.”

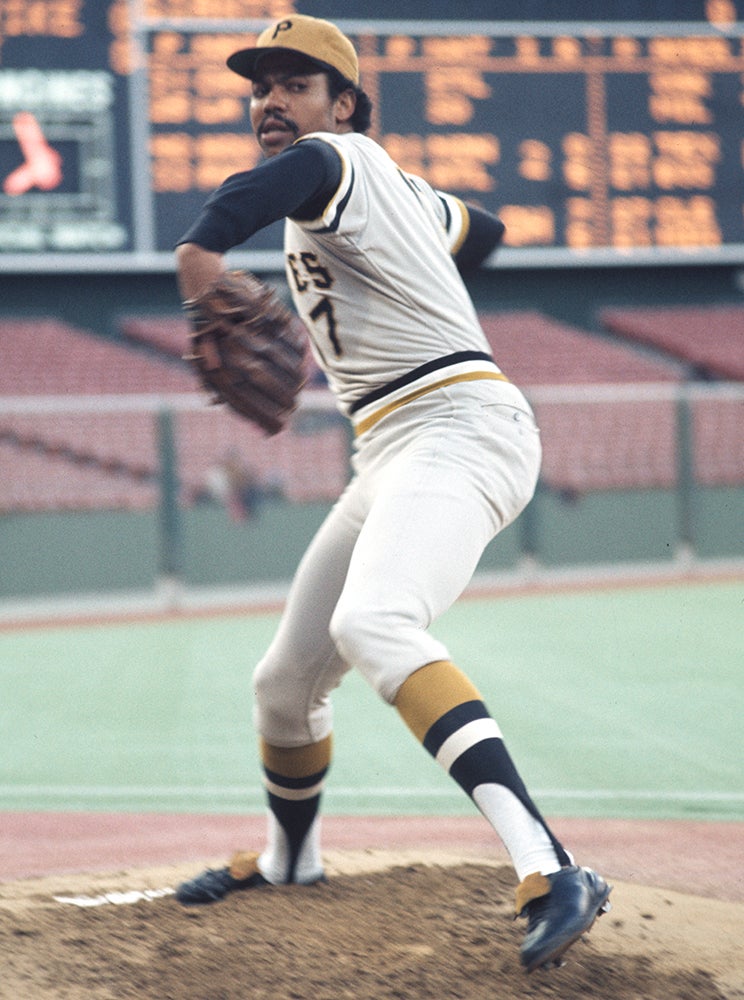

Still, Ellis continued to pitch well. He finished the 1970 season with a 13-10 record and 3.21 ERA over 201.2 innings as the Pirates won the National League East title. Tabbed to start Game 1 of the NLCS vs. the Reds, Ellis and Gary Nolan each pitched nine shutout innings before the Reds scored three runs off Ellis in the 10th to secure a 3-0 win. Cincinnati swept the series, but Ellis had clearly established himself as the Pirates’ ace.

In 1971, Ellis started on Opening Day and was 6-3 by the end of May. He began June with a 9-0 shutout of the Cardinals and ran his record to 15-3 with 10 straight victories from May 27-July 17. Entering the All-Star break with a 14-3 mark, Ellis was named the starting pitcher for the National League. He retired six of the first seven batters he faced before Luis Aparicio singled to start the third inning. What followed became history when Reggie Jackson blasted an Ellis offering off a transformer atop the right field roof at Tiger Stadium.

Frank Robinson added another two-run homer off Ellis later in the frame to give the AL a 4-3 lead which would turn into a 6-4 win. Still, Ellis was in the middle of a remarkable season. On Sept. 1, he started for the Pirates in a game where Pittsburgh’s all-Black lineup was the first of its kind in AL or NL history. He tired down the stretch but still finished 19-9 with a 3.06 ERA and 11 complete games.

The Pirates once again won the NL East and Ellis started Game 2 of the NLCS vs. the Giants, allowing two runs over five innings and picking up the victory as Pittsburgh won 9-4. The Pirates won the series in four games but it was not without controversy for Ellis, who switched hotels when he said the bed at San Francisco’s Jack Tar Hotel was not big enough to accommodate his 6-foot-3 frame.

Ellis had a similar complaint about the Lord Baltimore Hotel during the World Series against the Orioles. He did not pitch as well as he had in the NLCS, allowing four runs over 2.1 innings in his Game 1 start. Baltimore won the first two games of the Fall Classic before the Pirates rallied to win in seven games. Ellis did not pitch again after Game 1 but let his feelings be known about the Pirates’ travel policies.

“They might gripe about this or that,” Pirates general manager Joe Brown told the Pittsburgh Press about Ellis and some of his teammates. “But when they get on the field, they still try just as hard to win.”

Ellis drew his second straight Opening Day assignment in 1972 as Bill Virdon took over the managerial reins from Murtaugh. Sporting a 2-1 record on May 5, Ellis arrived at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati with teammates Willie Stargell and Rennie Stennett. A security guard asked the players for identification, and Ellis said that Stargell and Stennett were admitted but were asked to vouch for Ellis’ identity. Ellis became angry and a verbal altercation ensued before the security guard sprayed Ellis with Mace. The Reds charged Ellis with assault, and Ellis in turn sued the Reds. But eventually, all charges were dropped and Ellis apologized.

Though slowed by a sore arm, Ellis finished the season 15-7 with a 2.70 ERA and an NL-leading home-run-per-innings pitched mark of 0.3. He drew the Game 4 start in the NLCS vs. the Reds – but with Pittsburgh needing only a victory to advance to the World Series, Ellis surrendered three unearned runs over five innings as Cincinnati won 7-1. The Reds then won Game 5 to eliminate the Pirates.

Ellis once again limited NL batters to the fewest home runs per innings pitched in 1973 with a 0.3 mark. His 3.05 ERA over 28 starts told a more accurate tale of his pitching than his 12-14 record as the Pirates struggled all season following the death of Roberto Clemente.

And Ellis once again found the national headlines for an off-the-field event when he appeared in uniform before a game with curlers in his hair. A photo of Ellis in curlers ran in papers around the country, prompting Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to order Ellis to cease and desist.

“There are many Black men who wear curlers in their hair,” Ellis told the Associated Press. “I wore them for two weeks before somebody took a picture. I didn’t hear anybody put out orders about Joe Pepitone when he wore a hairpiece that went down to his shoulders.”

Ellis’ recurring tendinitis in his right elbow limited him to just two starts in September in 1973, and following the season he had surgery to remove a cyst in his left knee. He was 1-1 in his first three starts in 1974 when controversy again found Ellis – once again involving Cincinnati – when he hit Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Dan Driessen to lead off a May 1 game in Pittsburgh. Ellis then walked Tony Pérez – it appeared he was trying to hit him as well – and went 2-and-0 on Johnny Bench before Murtaugh, who had returned as manager in 1974, pulled Ellis from the game.

Ellis later claimed he was retaliating against the Reds due to an ongoing feud between the teams that dated back to the 1972 NLCS.

“I told (teammate) Kurt Bevacqua (in Spring Training): ‘I’m going to go through their lineup and mow them down,’” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times. “He said: ‘Chateaubriand says you don’t.’ I said: ‘You got it.’ And I did it.”

His ongoing sore arm limited Ellis to seven starts in August and September combined, but five of those resulted in complete games as he finished the year 12-9 with a 3.16 ERA. The Pirates won the NL East title but Ellis was unable to pitch in the NLCS vs. the Dodgers, which Los Angeles won in four games.

Then in 1975, Ellis’ performance finally began to slip due to his arm problems. After failing to escape the first inning in back-to-back starts in early August, Ellis was demoted to the bullpen but refused the assignment. He was suspended for one day and then appeared at a team meeting where he was expected to apologize. Instead, Ellis railed against Murtaugh and Pirates management and was quickly suspended for 30 days. The sentence was reduced to two weeks but the damage had been done during a season where he went 8-9 with a 3.79 ERA. The Pirates again won the NL East and Ellis pitched two shutout innings in relief in Game 1 of the NLCS as the Reds swept Pittsburgh.

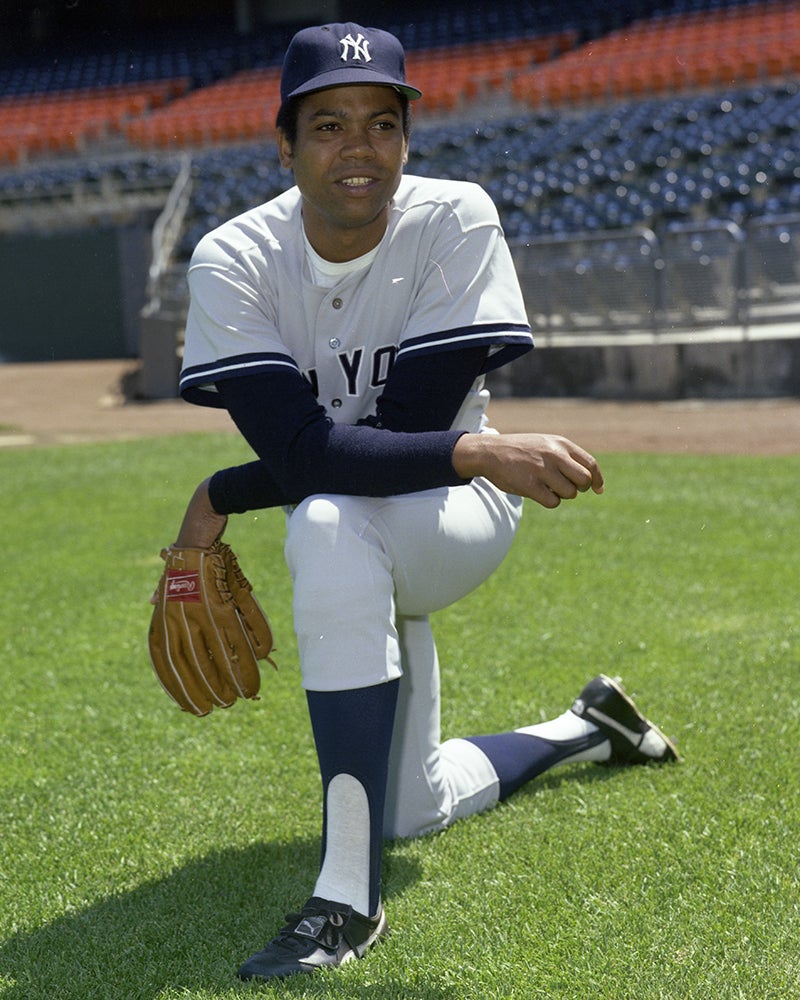

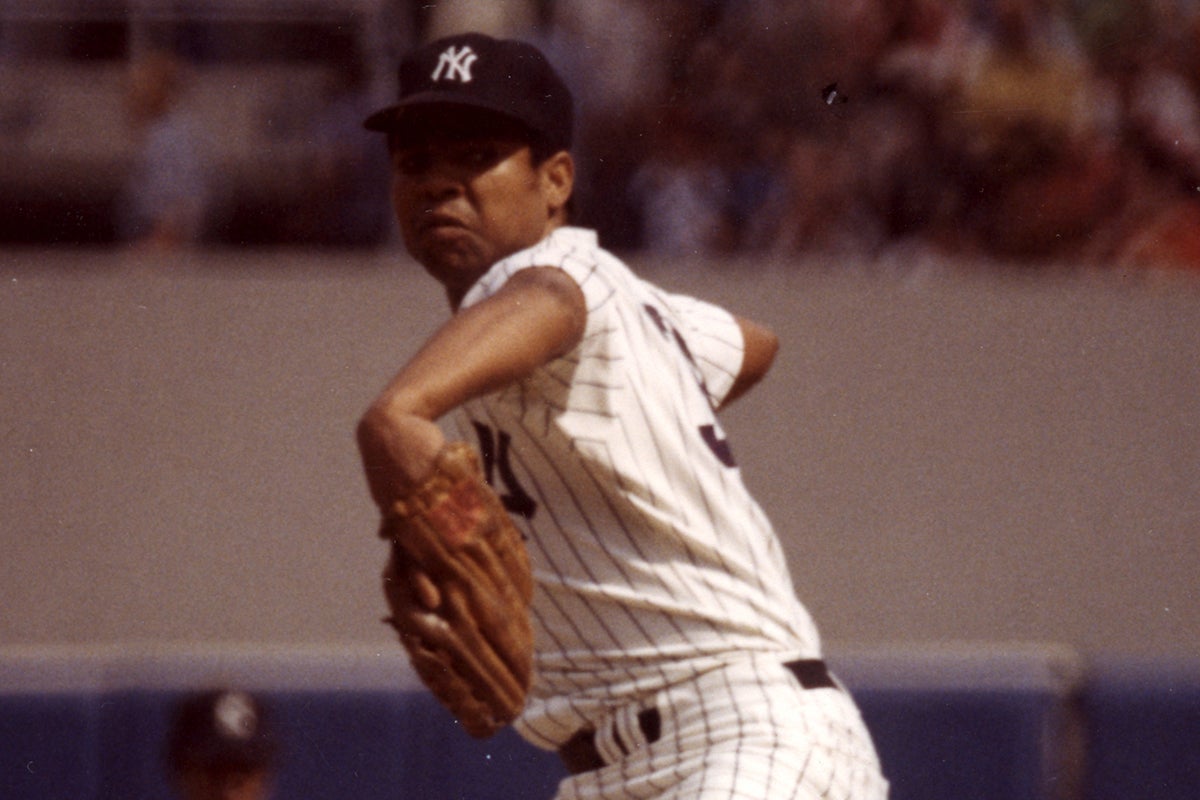

On Dec. 11, 1975, Ellis was traded to the Yankees with Ken Brett and Willie Randolph for pitcher Doc Medich.

Ellis settled in quickly in New York, heartily endorsing Randolph as the team’s new second baseman – “He’s one of the next superstars of the American League,” Ellis told the Bergen County Record that spring – and won seven straight starts from early June to mid-July. He finished the season 17-8 with a 3.19 ERA and started and won Game 3 of the ALCS vs. the Royals, allowing three earned runs over eight innings in a 5-3 Yankees win. New York advanced to the World Series against the Reds, where Ellis took the loss in Game 3 – allowing four runs over 3.1 innings as Cincinnati steamrolled past the Yankees in a four-game sweep.

It would be the last of Ellis’ seven postseason appearances.

Ellis made $80,000 in 1976 and expected a hefty raise in 1977. When that was not forthcoming, Ellis criticized Yankees owner George Steinbrenner publicly during Spring Training.

“He wants to take credit when we win,” Ellis told the Miami Herald. “I think he should stay up in his office, push his buttons, count his money and stay the hell out of the locker room.

“Now I hear they’re talking about trading me to Oakland. They think they’re gonna punish me.”

Three weeks later, the Yankees sent Ellis, Larry Murray and Marty Perez to the A’s in exchange for pitcher Mike Torrez, who would win 14 games for New York that year while helping the Yankees capture their first World Series title in 15 seasons.

Ellis, meanwhile, made seven starts for Oakland before his contract was sold to the Rangers. His departure from the A’s was hastened when Ellis set fire to charts he was asked to keep when he was not pitching.

“I said ‘Bleep these charts,’ and I set ’em on fire,” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times. “They thought the clubhouse in Cleveland was on fire.”

Ellis went 10-6 with a 2.90 ERA for Texas, finishing the year 12-12 with a 3.63 ERA overall. It would be the fifth-and-final time Ellis would pitch at least 200 innings in one season.

Ellis went 9-7 with the Rangers in 1978 but posted a 4.20 ERA and struck out just 45 batters in 141.1 innings, missing much of August and September with a groin injury. He also battled with manager Billy Hunter, fighting against Hunter’s edict that players could not drink in the bar of any hotel where the club was staying.

“You put your life at stake when you go outside the hotel bar to drink when you’re an athlete,” Ellis told United Press International in the spring of 1979. “I told (Hunter) I wasn’t going to go outside to get drunk. I don’t get drunk but I wasn’t going to take a chance on someone becoming involved in fisticuffs with me because I’m not a fighter.”

The relationship between Ellis and Hunter degraded to the point where Hunter told Ellis not to accompany the team on its last road trip of the season. While Ellis was away from the team, the Rangers fired Hunter.

In 1979, Pat Corrales took over as manager and Ellis began the season as the team’s No. 5 starter. But after posting a 1-5 record and 5.98 ERA, Ellis was traded to the Mets on June 15 in exchange for Mike Bruhert and Bob Myrick. But things did not improve in New York as Ellis went 3-7 with a 6.04 ERA with the Mets.

On Sept. 21, the Pirates brought Ellis home – purchasing his contract from the Mets as they battled with the Expos for the NL East title.

“I’m a Pirate! I always said I’d die a Pirate!” Ellis told the AP following the transaction. “Everyone (in Pittsburgh) is thinking about winning the pennant, they’re not thinking about controversy.”

Ellis made three appearances for Pittsburgh, starting against the Expos on Sept. 24 and allowing two runs over four innings in a 7-6 loss. He made two scoreless relief appearances before the season ended with the Pirates as division champions. Pittsburgh did not include him on its postseason roster.

The Pirates went on to win the World Series. Ellis became a free agent on Nov. 1, 1979. In the spring of 1980, Ellis officially retired.

“I had no desire,” Ellis told the Los Angeles Times. “The drugs and alcohol had really gotten rotten to me, and I didn’t give a …”

That summer, Ellis entered a rehabilitation clinic. When he got sober, he began helping others dealing with addiction.

Ellis pitched in amateur leagues in the 1980s and shared his story with a wide audience through motivational speaking engagements. But in his early 60s, his liver began to fail.

Ellis passed away on Dec. 19, 2008. Over 12 big league seasons, Ellis was 138-119 with a 3.46 ERA. He pitched for two teams that went on to win the World Series and six other squads which qualified for the postseason.

Curiously, advanced metrics don’t think much of Ellis’ career. He is the only pitcher in history with a Wins Above Replacement figure of 15.0 or lower with at least 135 wins, a .500-or-better winning percentage and a sub-3.50 ERA. Yet in two-thirds of his big league seasons, Ellis’ team was playing critical games in October.

It may be the best gauge of an on-field career that drew far fewer headlines than his off-the-field life.

“I can’t stop people from using drugs, but if they make that initial step, I think I can help,” Ellis said in 1985. “When I was playing ball and I was drugging, I would always help someone else and not see myself. But I’ve learned to help myself and help others, too, rather than helping others and not thinking I’m worthy of being helped.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum