- Home

- Our Stories

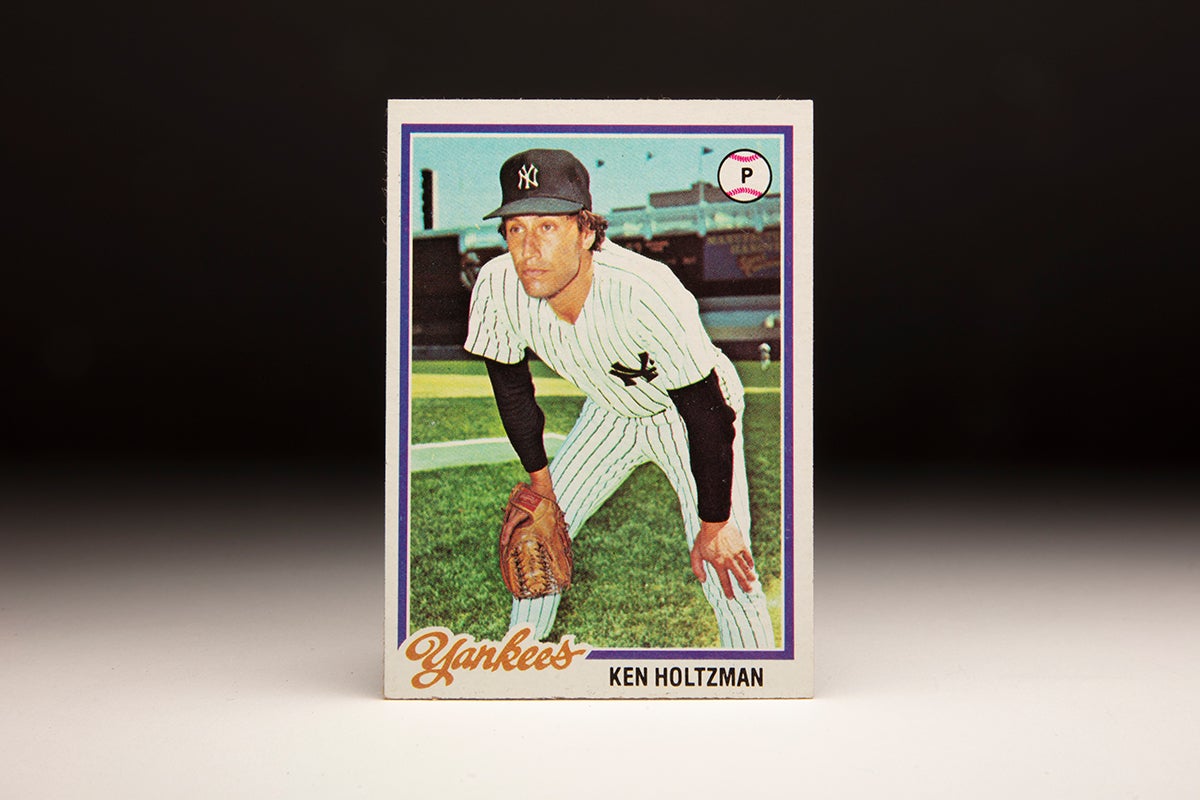

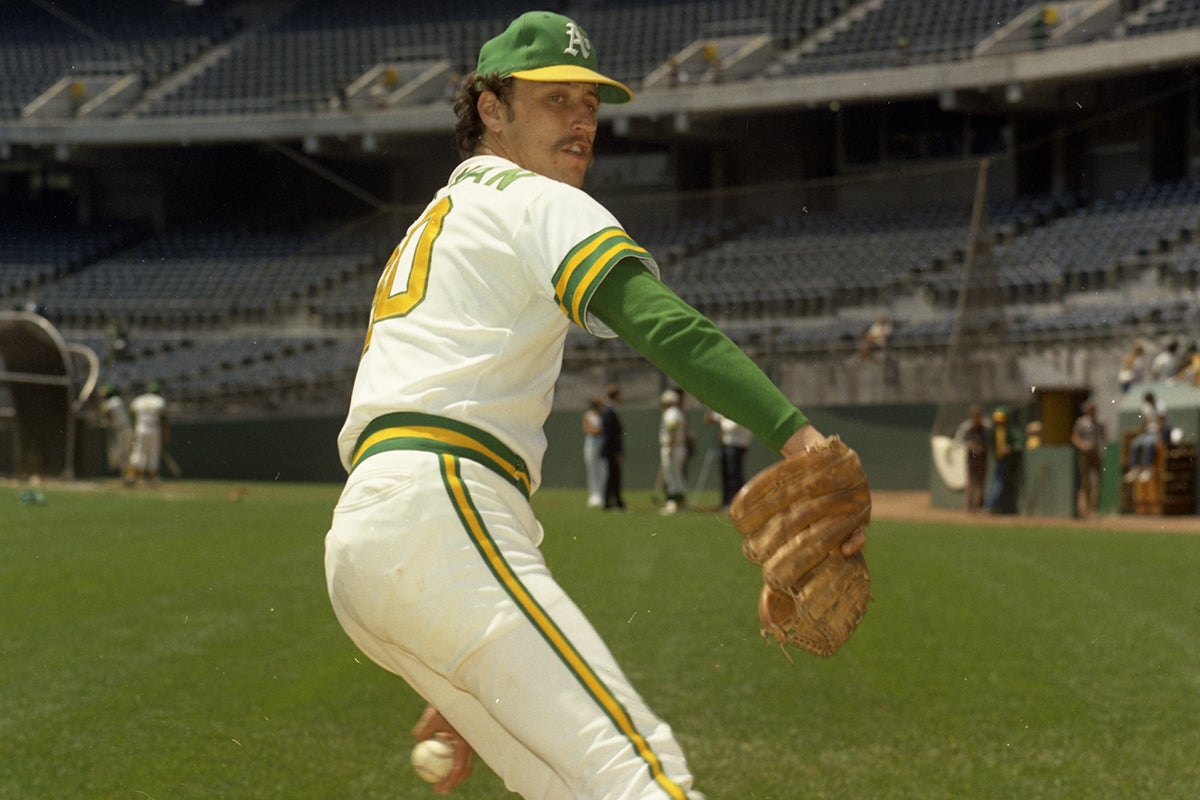

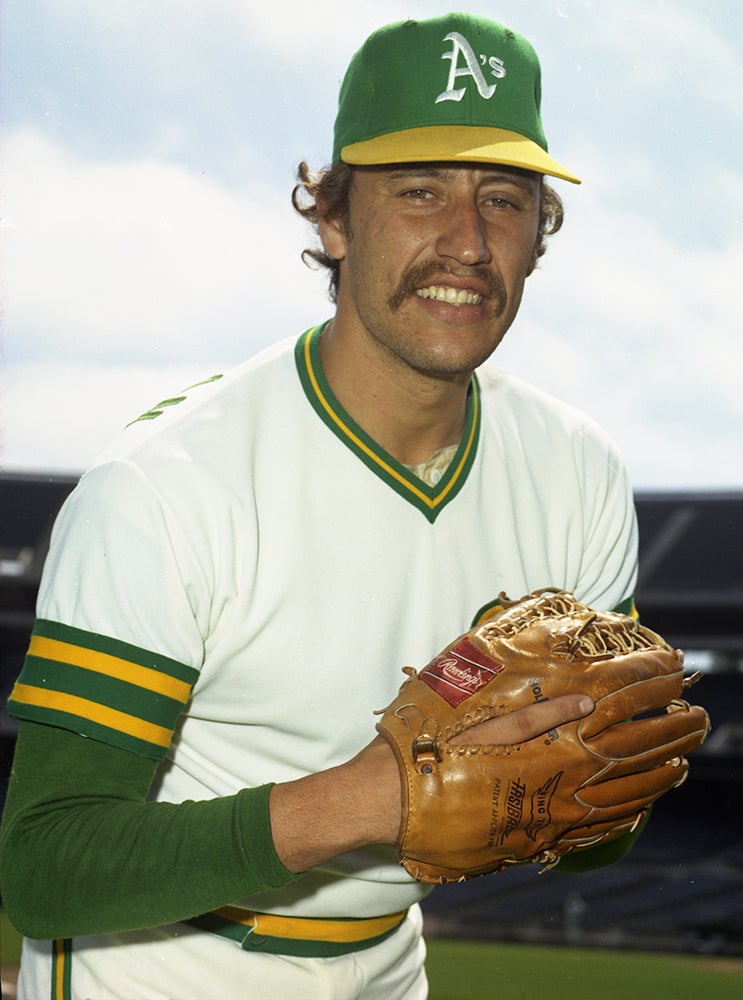

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Ken Holtzman

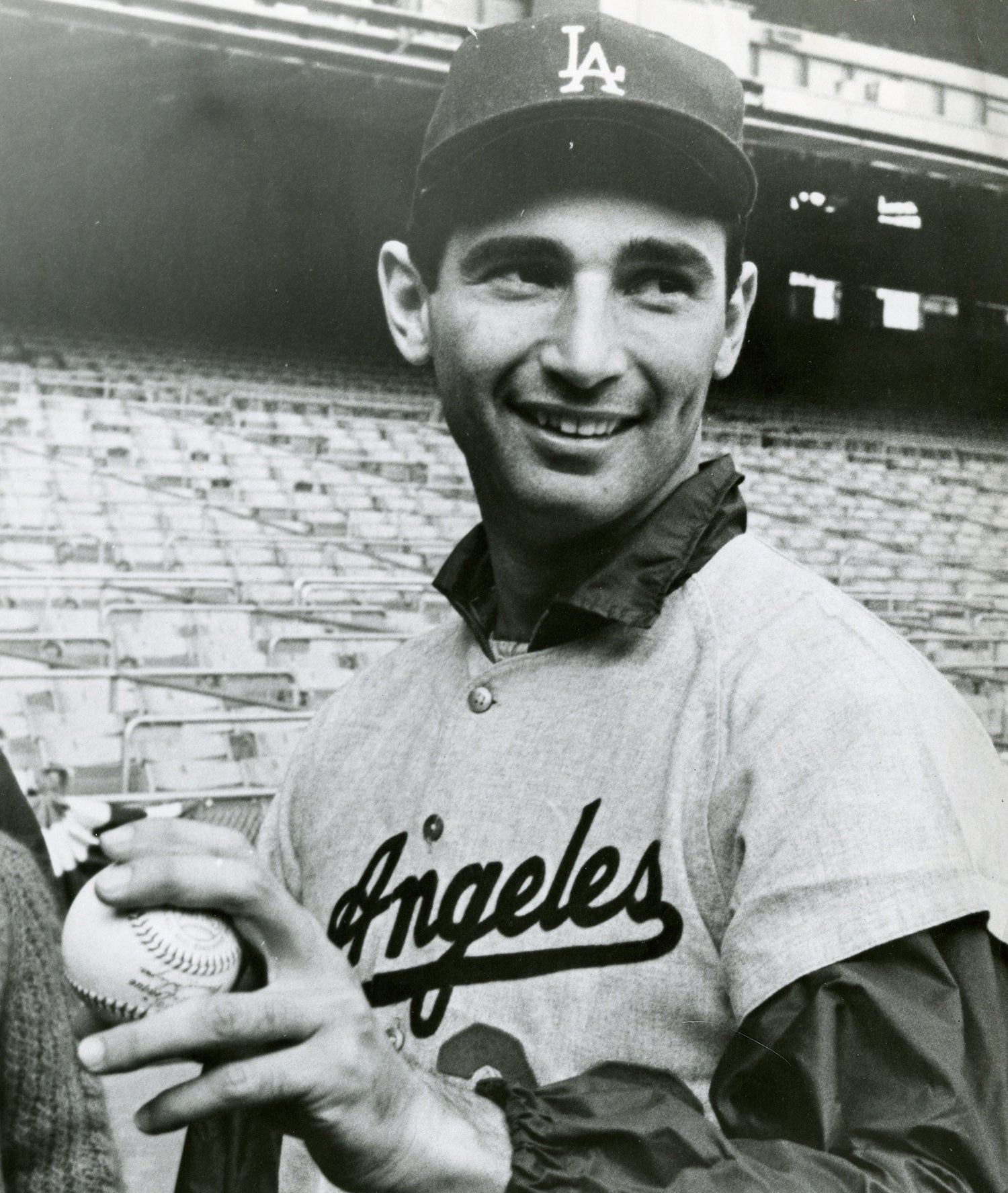

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Ken Holtzman

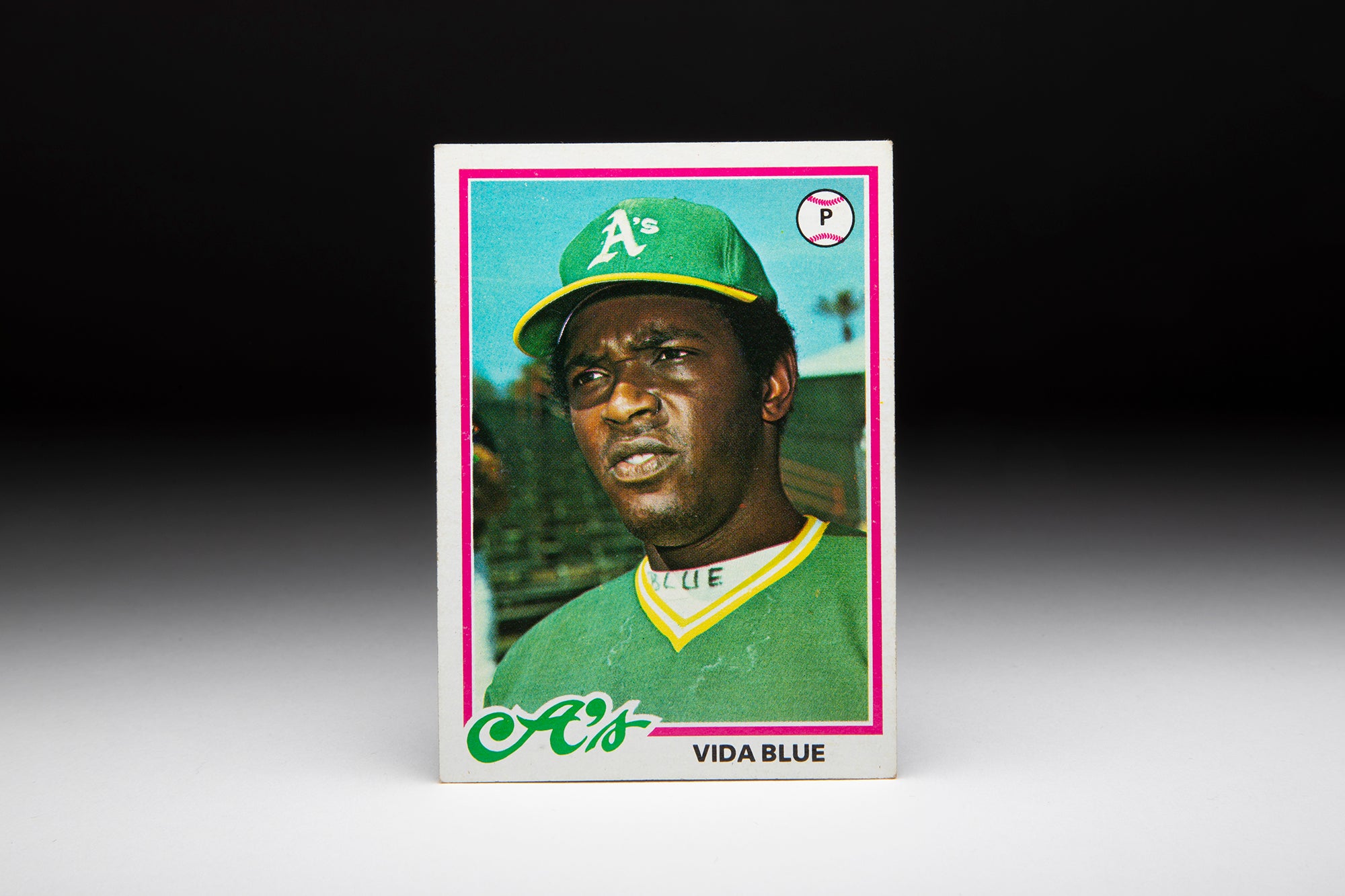

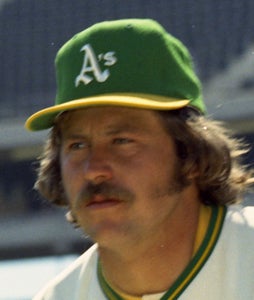

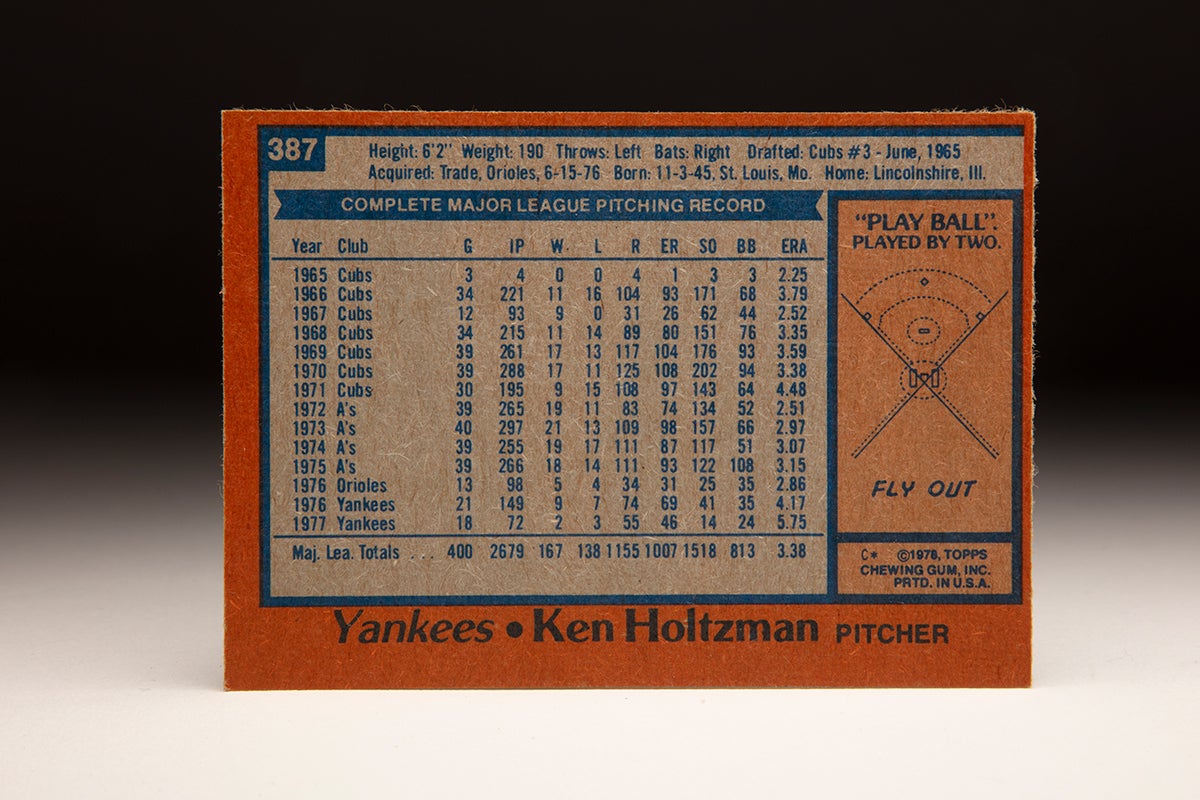

He was one of the aces of the 1970s Athletics, bolstering a rotation featuring homegrown stars Catfish Hunter and Vida Blue when he was traded to Oakland following the 1971 season.

Ken Holtzman was as responsible as anyone for the team’s three championships, going 4-1 in the World Series over three seasons. But when he had two more chances to pitch in the Fall Classic for the Yankees in 1976 and 1977, Holtzman never got into a game.

Those curious decisions by Yankees manager Billy Martin remain a part of Holtzman’s story to this day.

Born Nov. 3, 1945, in St. Louis, Holtzman was the oldest of three brothers in a tight-knit Jewish family that lived in nearby University City, Mo. By the time he was seven, Holtzman was pitching for local amateur teams.

“I absolutely did not push him,” Holtzman’s father Henry told the St. Louis Jewish Light in 1984. “He just loved to pitch. He forsake almost everything else for baseball. He wouldn’t fool around with other boys after a game.”

Holtzman became a star for University City High School and pitched the team to a state title in his senior season in 1963, winning most valuable player honors in the tournament. But at 5-foot-8, Holtzman was not deemed to be a pro prospect and instead enrolled at the University of Illinois.

While at Illinois, Holtzman grew six inches and was selected by the Cubs in the fourth round of the inaugural MLB Draft in 1965. He signed for a reported $65,000 bonus and reported to Treasure Valley of the Pioneer League, where he went 4-0 in four starts before being promoted to Wenatchee of the Class A Northwest League. He went 4-3 with a 2.44 ERA in eight starts for Wenatchee – and the Cubs were so impressed that they brought Holtzman to Chicago in September.

He would not pitch in the minor leagues again.

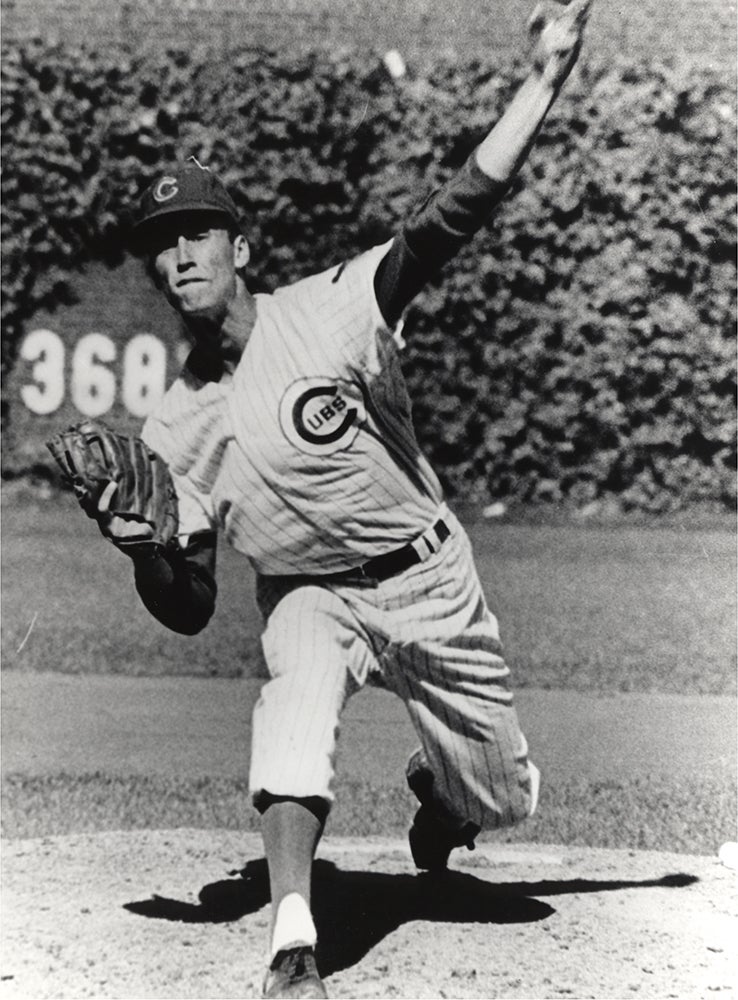

Holtzman worked in three games in relief for the Cubs at the end of the 1965 season for a team that wound up losing 90 games. Leo Durocher took over as manager in 1966 and was so impressed with Holtzman that he put the 20-year-old lefty in the starting rotation – even though Holtzman was still taking college classes.

Having transferred to the University of Illinois’ Chicago campus, Holtzman continued work on his education degree while Durocher worked his rotation around Holtzman’s availability.

“Until school lets out in June, he’ll be a weekend pitcher on the road,” Durocher told the Associated Press during the season’s first month in 1966. “At home, he’ll work in my rotation.”

Holtzman made his first big league start on April 24 vs. the Dodgers, shutting out Los Angeles on three hits over six innings to notch his first MLB win.

“Had to take him out,” Durocher told the AP. “The kid had only worked two innings all season and was tired. But it was a great win for him.”

Holtzman went 11-16 with a 3.79 ERA in 220.2 innings for a Cubs team that lost 103 games in 1966. But the season wound down on a positive note for Holtzman when he faced Sandy Koufax on Sept. 25, 1966, throwing a two-hitter as Chicago beat Los Angeles 2-1. It was the last regular season defeat of Koufax’s Hall of Fame career.

“It remains to this day one of my biggest thrills in baseball,” Holtzman told Gannett News Service in 2004.

In 1967, Holtzman began the season 5-0 before he was called up into an active role with the Illinois National Guard in May. He did not pitch again until August when he was granted weekend passes, and Holtzman worked four more games the rest of the season – winning them all to finish the year 9-0 with a 2.53 ERA. Among pitchers with at least 10 starts in one season, Holtzman is the only National League hurler to have at least nine wins and no losses in one year.

Holtzman continued to serve with his National Guard unit in 1968 but was able to take regular turns in the Cubs’ rotation, going 11-14 with a 3.35 ERA in 215 innings. Then in 1969, Durocher’s rebuilding job with Chicago came to fruition. The Cubs led the newly formed National League East for much of the season as Holtzman began the year with 10 wins in his first 11 decisions.

A summer slump followed but Holtzman rebounded and pitched a no-hitter against the Braves on Aug. 19 in a 3-0 Cubs victory. Holtzman walked three and did not strike out a batter, becoming the first pitcher to throw a no-hitter without recording a strikeout since Sam Jones for the Yankees in 1923. No one has done it since.

“I knew I didn’t strike out anybody,” Holtzman told the AP. “So I stuck with my fastball, my best pitch all the way. I got marvelous support, especially from my infield.”

Holtzman improved to 16-8 after another win over the Braves on Aug. 31. The Cubs were four games in front of the Mets in first place at that point but lost 11 of their next 13 – a stretch that flipped the standings and left the Mets four-and-a-half games ahead of Chicago.

Holtzman’s final game of the season came Oct. 1 vs. the Mets, by which time the division title was no longer in play. Holtzman finished the year 17-13 with a 3.58 ERA in 261.1 innings.

Holtzman posted similar numbers in 1970, going 17-11 with a 3.38 ERA while striking out 202 batters – the first and only time Holtzman reached the 200-K mark in his career. But in 1971, Holtzman clashed with Durocher and finished 9-15 with a 4.48 ERA. He joined an exclusive club, however, by pitching his second no-hitter, blanking the Reds on June 3 in a 1-0 Chicago win where Holtzman scored the only run on a third-inning single by Glenn Beckert.

The closest the Reds came to a hit was when catcher Johnny Bench tried to bunt his way on in the seventh inning. But the ball eventually rolled foul and Bench subsequently flew out to right field.

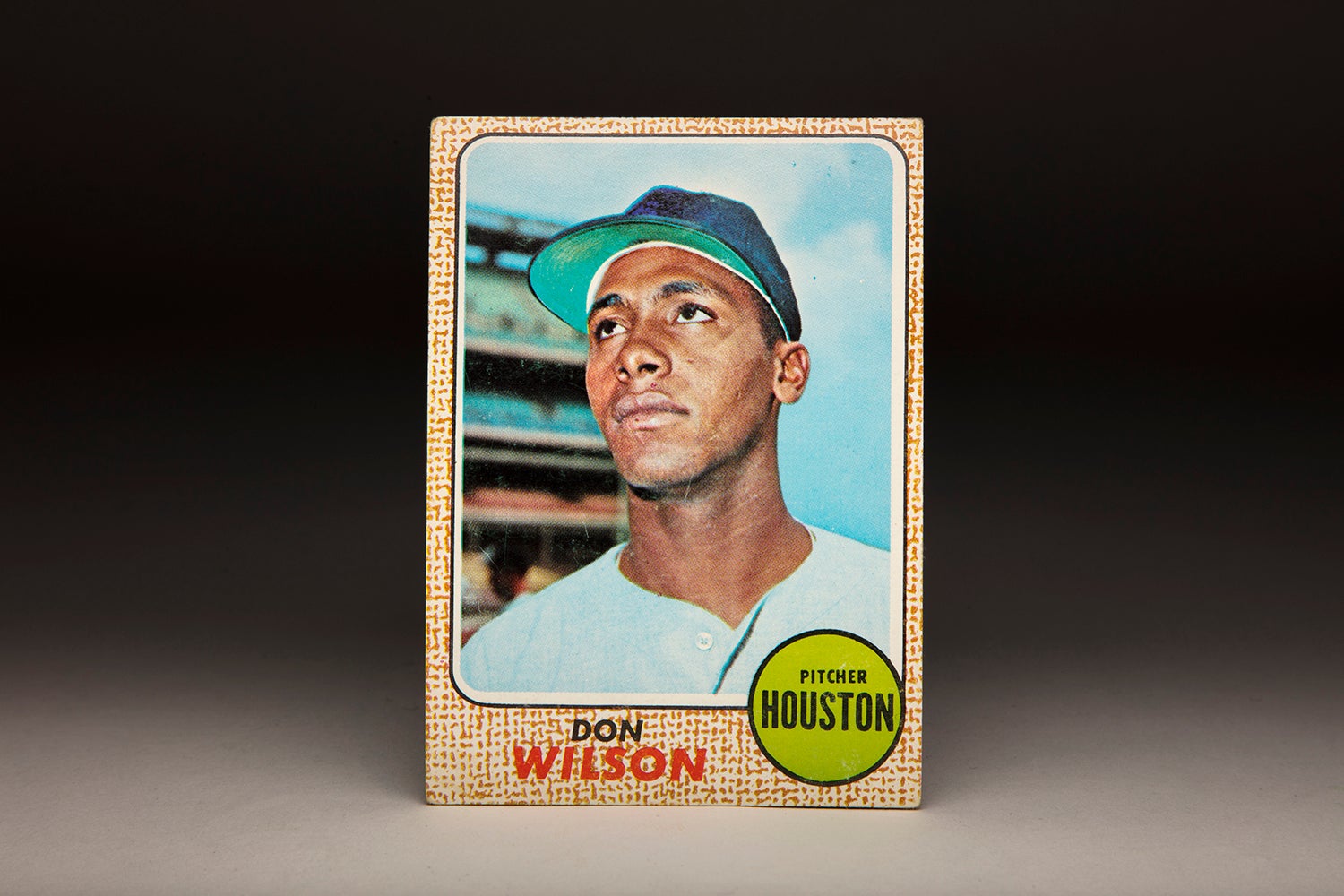

Holtzman became the first Cubs pitcher with two no-hitters. At the time, Holtzman, Jim Bunning, Jim Maloney and Don Wilson were the only active pitchers with multiple no-hitters.

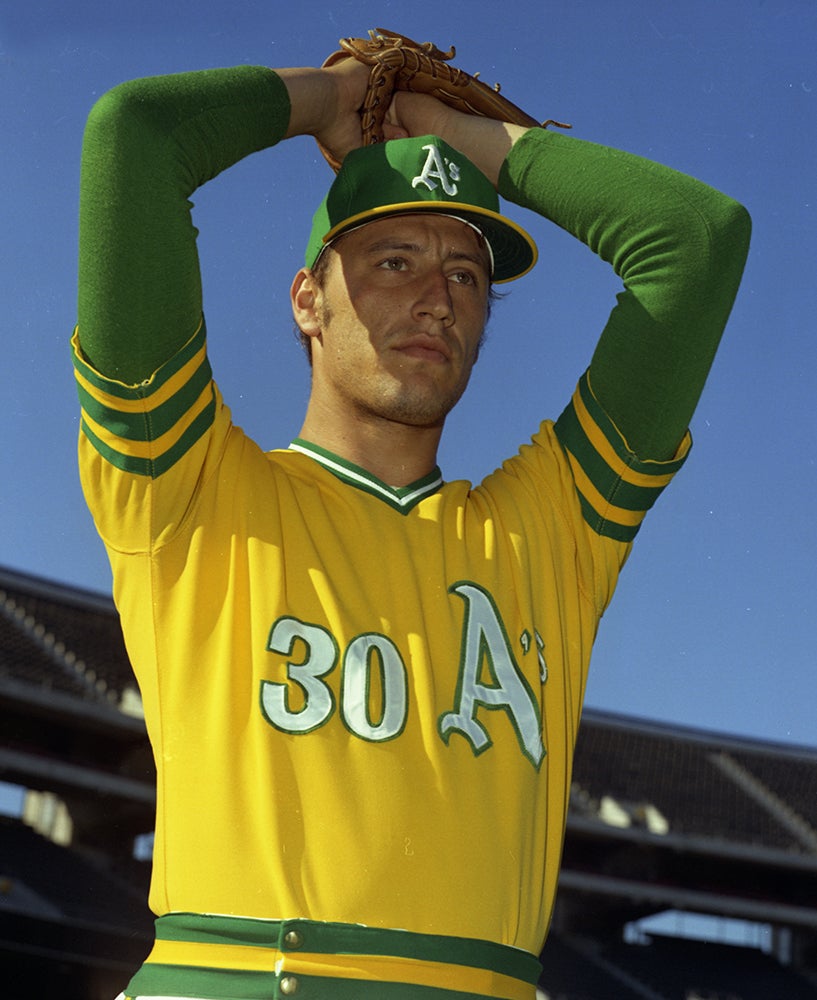

But the no-hitter was not enough to convince the Cubs – or Holtzman – that the pitcher’s future was in Chicago. So on Nov. 29, 1971, Athletics owner Charlie Finley – looking for additional starting pitching for a staff that featured Hunter and Blue – sent outfielder Rick Monday to the Cubs in exchange for Holtzman, who had asked to be traded.

“We needed pitching insurance and we got it in Holtzman,” Athletics manager Dick Williams told United Press International. “With Blue Moon Odom uncertain and Chuck Dobson going in the hospital for surgery Dec. 17, we had physical problems in our pitching.”

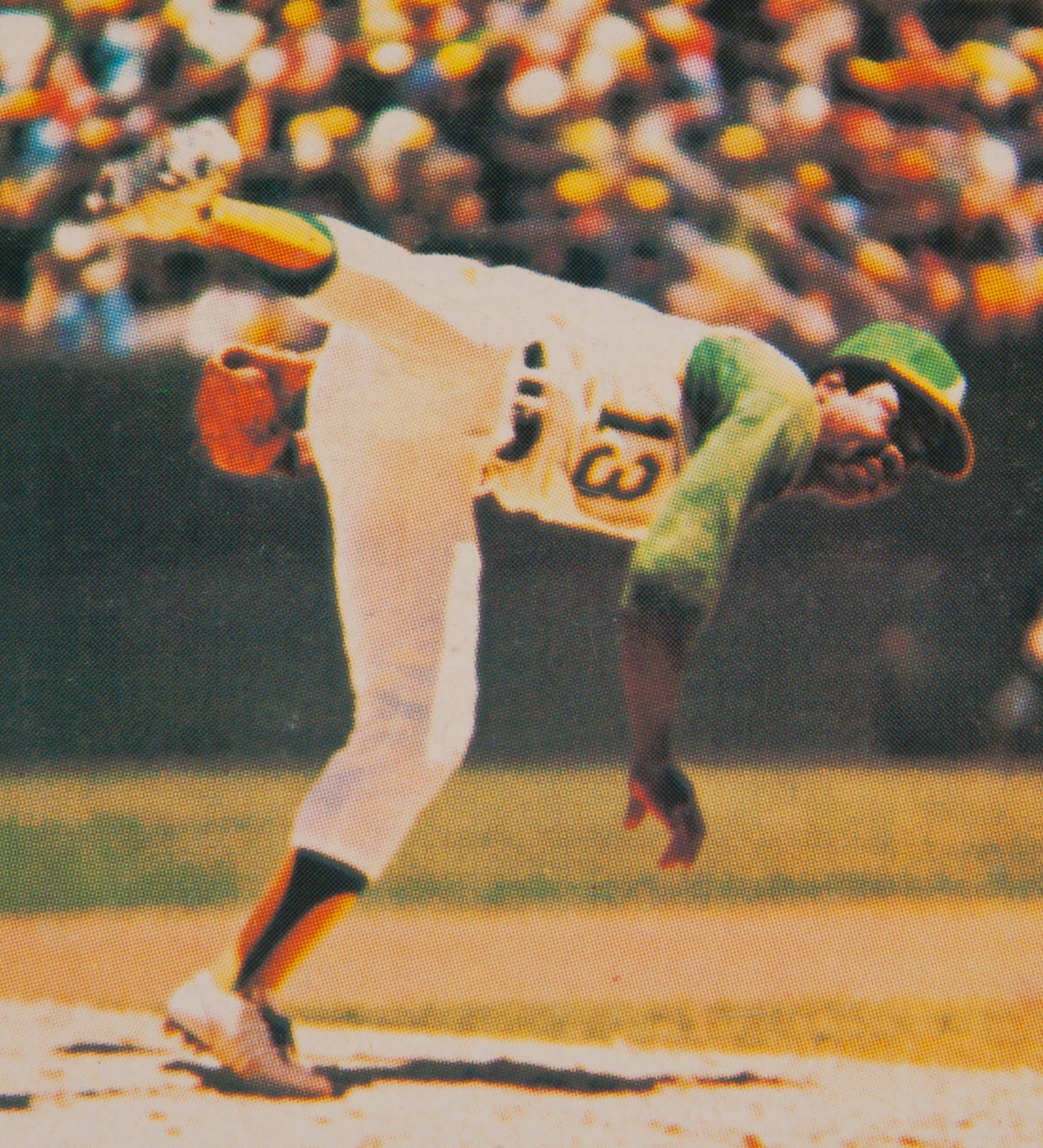

Holtzman did more than just provide insurance. In four seasons with the A’s, he won 77 regular season games plus six more in the postseason, giving Oakland three aces in a rotation that carried the Swinging A’s to four AL West titles and three World Series championships.

Holtzman made his first Opening Day start in 1972, allowing two runs over eight innings to earn a no-decision in Oakland’s 4-3 win over Minnesota. Blue was coming off a legendary 1971 season where he won the AL Cy Young Award and AL MVP Award but was embroiled in a contract dispute with Finley.

Holtzman helped fill the void until Blue returned in May, winning 13 games before the All-Star break and then going 4-0 in September to finish the season with a 19-11 record and 2.51 ERA. He made one start in the ALCS vs. the Tigers, allowing two runs over four innings before being lifted for a pinch-hitter as the Tigers won 3-0 behind 14 strikeouts from Joe Coleman.

The Athletics won the series in five games, leaving Holtzman in line to start Game 1 of the World Series against the favored Cincinnati Reds. He allowed two runs over five innings and picked up the 3-2 win with the help of a combined four shutout frames from Rollie Fingers and Blue, who was moved to the bullpen by Williams for the postseason.

Ed Mickelson, Holtzman’s high school coach at University City and a former first baseman for the Cardinals, Browns and Cubs, cheered on Holtzman from a box seat at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium.

“There was no way I was going to miss this one even if I had to sit in the worst seat in the park,” Mickelson told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “Ken didn’t seem suited for pro ball. That’s because he was so small and thin as a kid.”

But by 1972, Holtzman had evolved into a durable workhorse. He returned to start Game 4, pitching 7.2 innings while allowing just one run in a contest Oakland won 3-2 with two runs in the bottom of the ninth. But the Reds won the next two games to knot the series at three games apiece, and Williams turned to Odom to start Game 7.

Odom allowed one run over 4.1 innings and Hunter retired the side in the fifth with the game tied at 1. Then Oakland scored twice in the top of the sixth, and Hunter kept the Reds off the board in the sixth and seventh before allowing a leadoff single to Pete Rose in the eighth. Williams then summoned Holtzman to face the lefty-swinging Joe Morgan, but Morgan foiled the strategy by doubling and sending Rose to third.

Fingers relieved Holtzman at that point and allowed a sacrifice fly by Tony Pérez but no additional damage. Fingers then retired the side in the ninth to preserve Oakland’s 3-2 win and the franchise’s first World Series title since 1930.

But the Athletics’ championship machine was just getting started. Holtzman began the 1973 season in a groove again, improving to 11-3 with a two-hit shutout against the Tigers on June 9. He was named to his second (and what turned out to be his final) All-Star Game that season and was 15-9 at the break, recording two outs in relief of AL starter Catfish Hunter in the second inning of the Midsummer Classic. Holtzman finished the year 21-13, one of three 20-game winners (along with Hunter and Blue) on the A’s.

Holtzman started Game 3 of the ALCS vs. Baltimore, pitching 11 innings in a 2-1 Oakland win. The A’s once again needed all five games to advance to the World Series, lining up Holtzman once again for the Game 1 start in the Fall Classic. He allowed one run over five innings against the Mets, scoring the game’s first run when he doubled in the third inning and scored on a ground ball by Bert Campaneris that was ruled an error on New York second baseman Félix Millán. Holtzman earned the win in Oakland’s 2-1 victory.

Following the victory, writers reminded Holtzman about his early-career comparisons to Sandy Koufax and how he was creating his own World Series legacy. Holtzman, however, did not appreciate the comparison.

“There is nobody as great as Koufax,” Holtzman told the AP after Game 1. “The way some of the Chicago writers wrote about me and my career, I wouldn’t even read it. It wasn’t only poor writing but poor reporting.

“The biggest break in my life was when I was traded to Oakland. You don’t know everything that went on in Chicago. I don’t want to talk about it.”

Holtzman was not as effective in his Game 4 start, allowing a three-run home run to Rusty Staub in the bottom of the first before getting his first out of the inning. But after a walk to John Milner and a single by Jerry Grote, Williams pulled Holtzman in a game Oakland lost 6-1.

For the fourth straight postseason series, the A’s pushed things to the final game, and Holtzman got the start in Game 7. This time, Oakland jumped out to a 5-0 lead and Holtzman pitched into the sixth before being relieved by Fingers. The A’s won 5-2 to clinch their second straight title.

Eligible for arbitration in the first round of that process heading into the 1974 season, Holtzman found himself in the headlines when the San Francisco Chronicle erroneously reported – after being tricked into thinking they were talking to Holtzman on the phone – that Holtzman was mad at both Finley and MLB Players Association executive director Marvin Miller. The story eventually got straightened out and Holtzman won his case and a salary of $93,000.

The Athletics won their fourth straight division title in 1974 while Holtzman went 19-17 with a 3.07 ERA for new manager Alvin Dark. After Oakland lost Game 1 of the ALCS to the Orioles, Holtzman evened the series with a five-hit shutout and was not needed again as Oakland won in four games.

Then in the World Series against the Dodgers, Holtzman started Game 1 and was pulled in the fifth after allowing one unearned run over 4.1 innings. Fingers slammed the door to preserve the Athletics’ 2-1 lead, and Oakland ended up winning 3-2. Holtzman returned to start Game 4 and allowed two runs over 7.2 innings in a 5-2 Oakland win, homering off Andy Messersmith in the third inning for the game’s first run.

The A’s then won Game 5 to wrap up the title and cement their dynasty. But it was a reign that was about to end.

Holtzman and Finley again met in arbitration prior to the 1975 season, with Holtzman asking for $112,000 and Finley offering the same $93,000 that Holtzman made in 1974.

“We pay our players well,” Finley told the AP during the arbitration process. But many of his players disagreed, setting in motion the dismantling of the dynasty that was soon to come.

With Hunter having left the A’s for the Yankees following the 1974 season via a contract issue that made him a free agent, the Athletics’ three-pronged rotation attack was reduced to Holtzman and Blue. Holtzman went 18-14 with a 3.14 ERA and nearly notched his third career no-hitter, pitching 8.2 no-hit innings vs. Detroit on June 8 before Tom Veryzer doubled to break up the gem.

The A’s still won the AL West but fell to Boston in three games in the ALCS as Holtzman allowed four runs (two earned) over 6.1 innings in a 7-1 loss in Game 1. He returned to start Game 3 on just two days’ rest, allowing four runs (three earned) over 4.2 innings for his second defeat of the series.

It would be the final game of Holtzman’s career in Oakland.

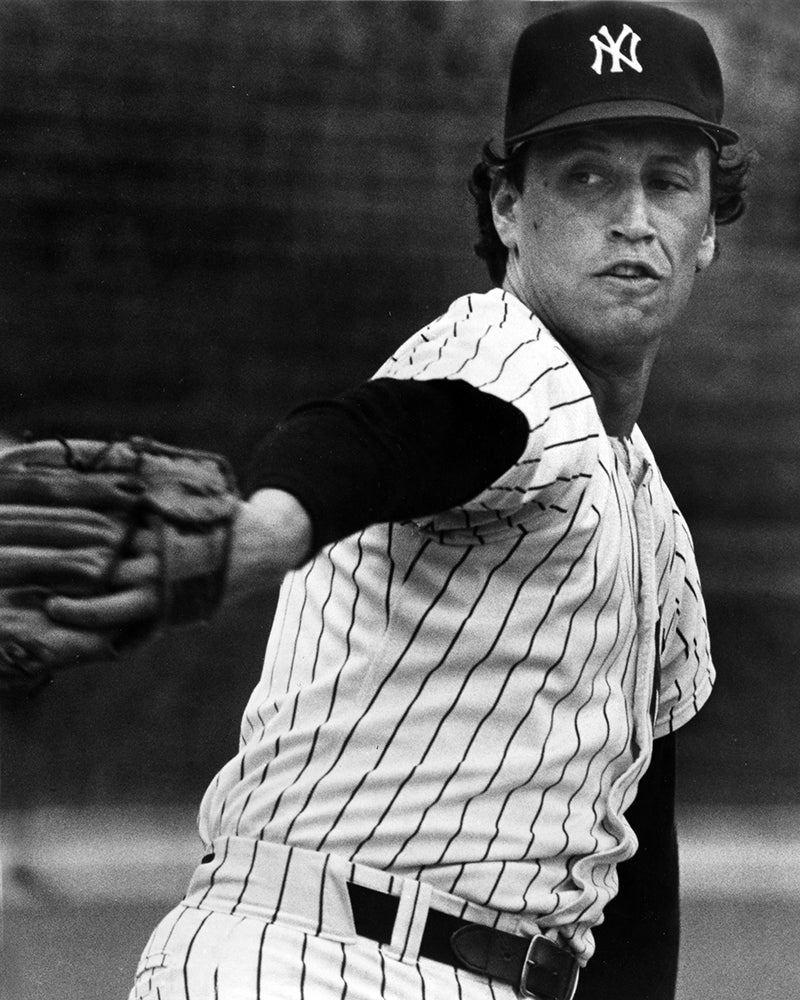

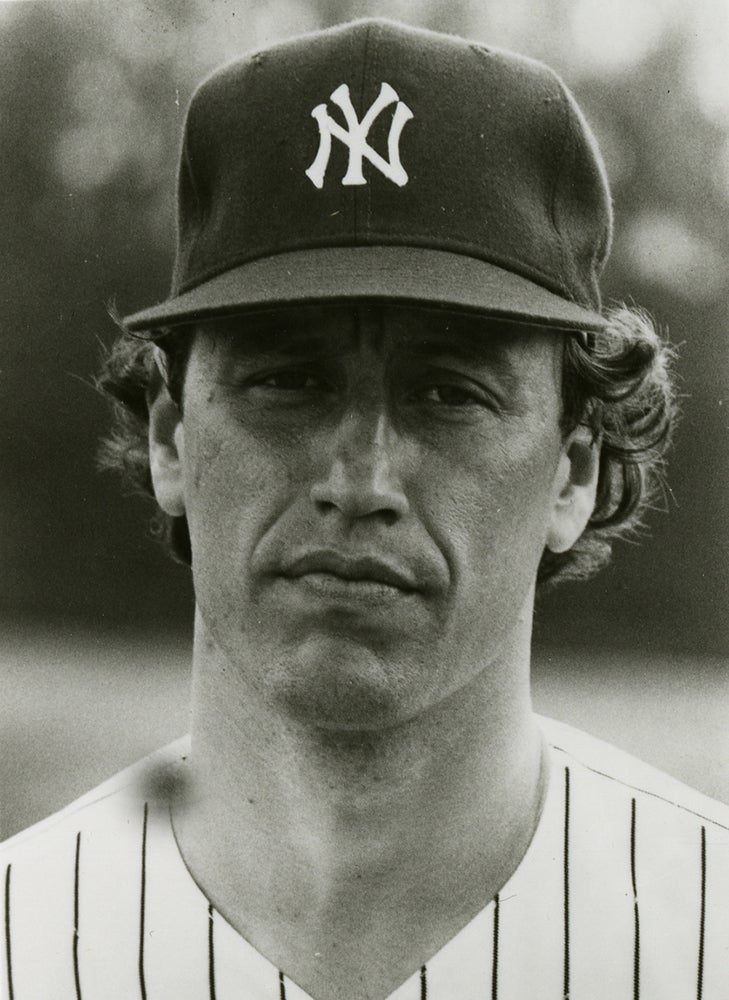

After an offseason where arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled that Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally were free agents because they played the season without signing a contract (thereby playing out their option year), free agency was suddenly thrust upon the owners in 1976. Finley responded trying to implement 20-percent pay cuts (the maximum allowed by the collective bargaining agreement) on several players before trading many of them, sending Holtzman, Reggie Jackson and a minor leaguer to the Orioles on April 2 in exchange for Don Baylor, Paul Mitchell and Mike Torrez. It would mark the start of a four-season roller coaster for Holtzman as he battled injuries and unexplained managerial moves while pitching for three Yankees teams that won the AL pennant.

Holtzman was 5-4 with a 2.86 ERA through 13 starts for the Orioles in 1976 when Baltimore and the Yankees made a huge trade, sending Holtzman, Doyle Alexander, Jimmy Freeman, Elrod Hendricks and Grant Jackson to New York in exchange for Rick Dempsey, Tippy Martinez, Rudy May, Scott McGregor and Dave Pagan on June 15. Five weeks later, Holtzman agreed to a five-year extension worth $825,000. He was moderately effective for the Yankees, going 9-7 with a 4.17 ERA in 21 starts to finish the year at 14-11. But he struck out just 66 batters over 246.2 innings, signaling that he was no longer able to dominate batters.

Holtzman did not pitch in the ALCS vs. the Royals as the Yankees advanced in five games. Then in the World Series, New York dropped the first three contests to the Reds. After Game 3, Yankees manager Billy Martin announced that Holtzman would start Game 5.

“I hope there is a (Game 5),” Holtzman told Knight News Wire. “If we do go to a fifth game, I’ll probably have to warm up 20 or 25 minutes. I haven’t pitched in three-and-a-half weeks. It’s hard to tell how you’re going to pitch when you lay off this long.”

Holtzman never got the chance as the Yankees lost Game 4.

Holtzman reported to Spring Training in 1977 with a rotation spot seemingly in hand. But after several rough starts in April and May, he was sent to the bullpen and pitched only occasionally the rest of the year. The Yankees won the AL pennant again but Holtzman went just 2-3 with a 5.78 ERA over 71.2 innings in 18 games. Once again, he did not pitch in the postseason as the Yankees won their first World Series title in 15 years.

Holtzman spoke with Yankees general manager Gabe Paul several times during the season, trying to find a way out. But with rumors rampant that Martin simply didn’t care for Holtzman, no solution was forthcoming.

“If you owned a company and went out and bought a $5 million machine that was never used, wouldn’t you either sell the machine or fire the foreman?” Holtzman rhetorically asked reporters, referring to Paul as “the foreman.”

Faced with being the missing man once again in 1978, Holtzman appeared in five games for the Yankees before the team traded him to the Cubs on June 10 in exchange for pitcher Ron Davis.

“I told my wife Michelle and she cried,” Holtzman told UPI about the trade. “She’s a Chicago girl and between us we must have 200 relatives in the city.”

Holtzman, however, was not effective in 23 games for the Cubs, going 0-3 with a 6.11 ERA. He was moderately more efficient in 1979, going 6-9 with a 4.59 ERA over 117.2 innings. But he struck out just 44 batters while walking 53.

Holtzman’s last game came on Sept. 19, 1979, his first appearance in more than five weeks. He shut out the Cardinals through seven innings, earning a no-decision in a 3-2 Chicago win. After the game, he told his father: “Dad, I’ve had enough.”

The Cubs released Holtzman on Oct. 3, and he did not seek another job. He went into the insurance business with Mutual of New York after his career, working many years outside of the game. He passed away on April 14, 2024, at the age of 78.

Holtzman retired with a career record of 174-150 with a 3.49 ERA and pitched for five different teams that won the World Series. He took pride in being the winningest Jewish pitcher in MLB history, even if he was unable to become the “next Sandy Koufax” – a label that stuck with him for much of his early MLB career.

“Being here today, you’re proud to be Jewish and represent a group that historically hasn’t been represented in great number in major league sports,” Holtzman told Gannett News Service at an event honoring Jewish players at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown in 2004. “But we all here made it to the major leagues, and I think we’re all quite proud of it.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum