- Home

- Our Stories

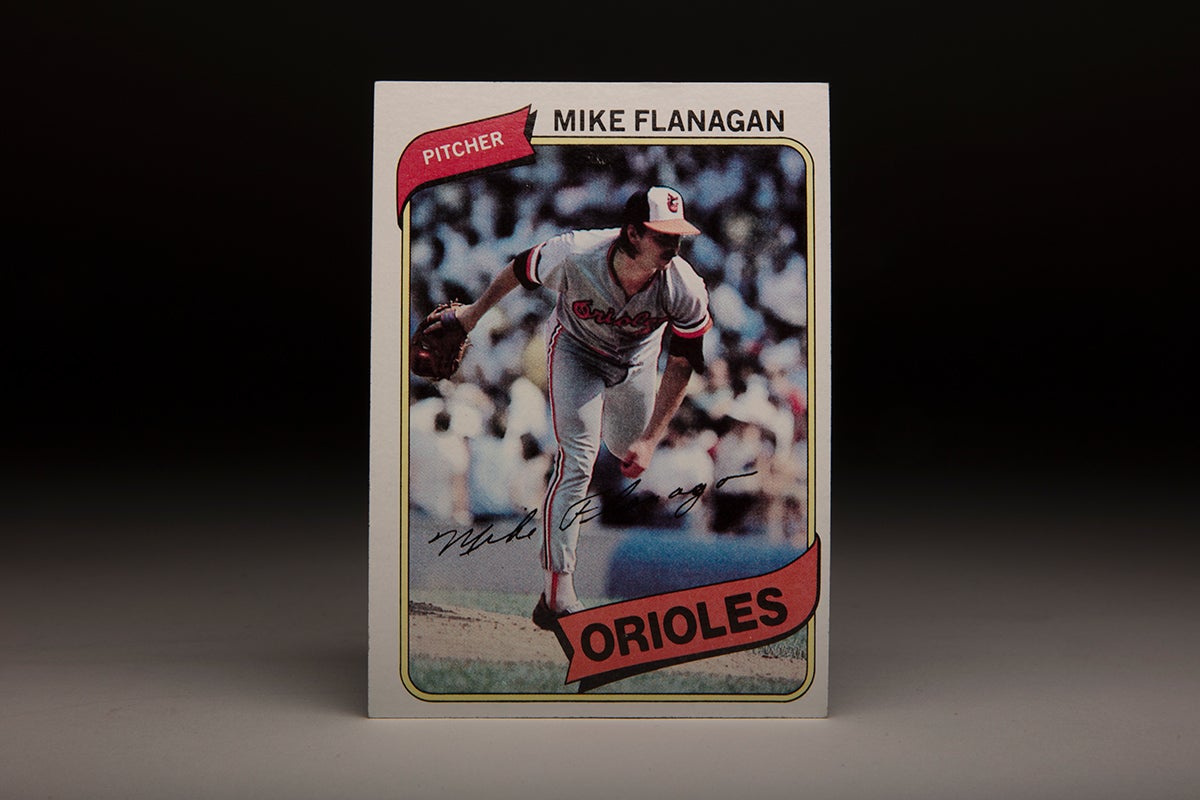

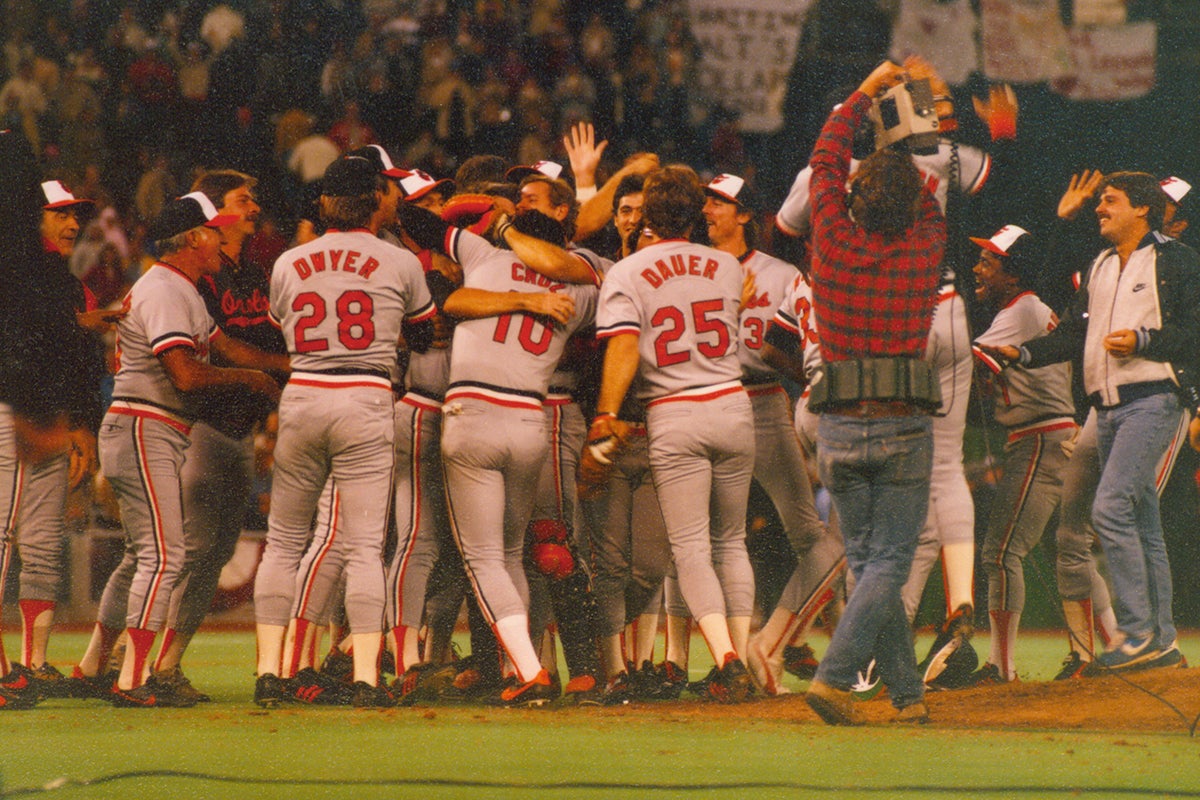

- #CardCorner: 1980 Topps Mike Flanagan

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Mike Flanagan

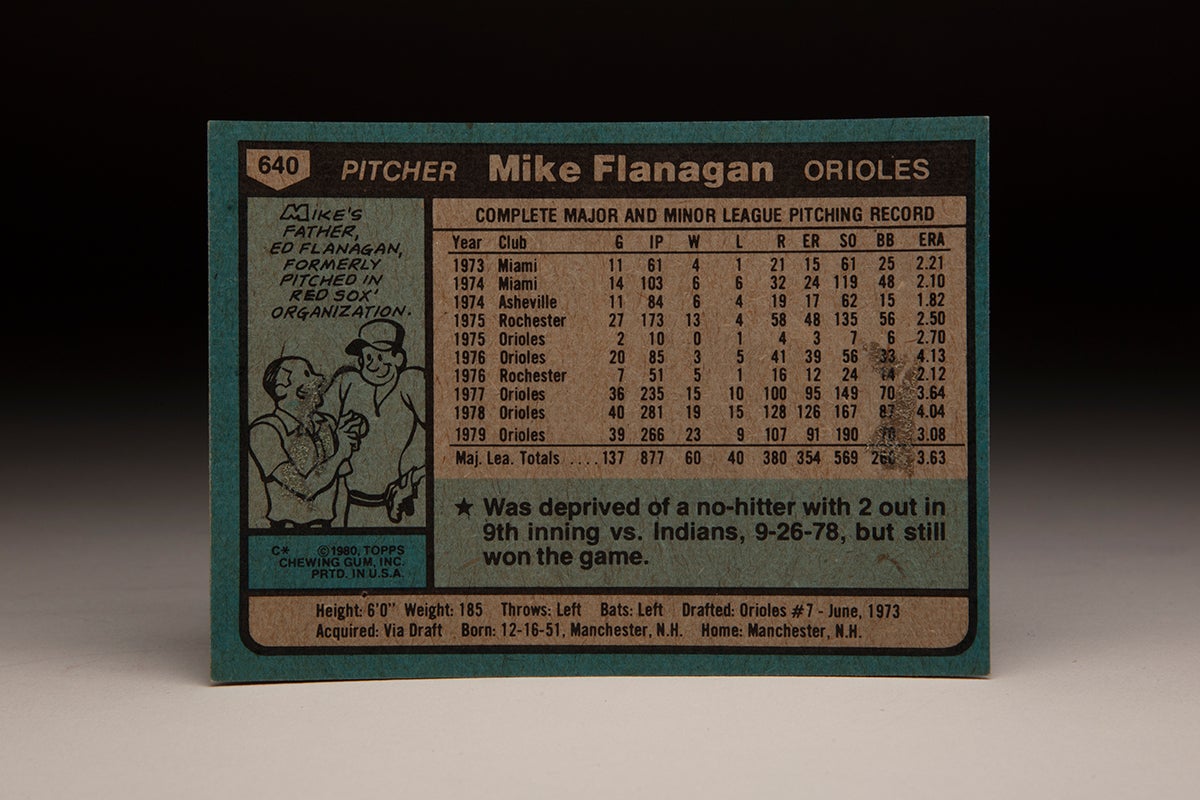

In a 12-year stretch from 1969-80, the Baltimore Orioles produced four different American League Cy Young Award winners. None had a larger margin of victory in the Cy Young Award race than Mike Flanagan, who was far and away the most successful starting pitcher in baseball in 1979.

For Flanagan, it marked the peak of a career that featured two pennants and one World Series title – and a life that ended in tragedy.

Born Dec. 16, 1951, in Manchester, N.H., Michael Kendall Flanagan was born into a baseball family. His grandfather was a barnstorming ambidextrous pitcher, and his father, Ed Flanagan, pitched for seven seasons in the 1940s and 50s in the minor leagues – including a stop in Oneonta, N.Y., 30 miles from the Hall of Fame, in 1948.

“I was surrounded by (baseball),” Mike Flanagan told The New York Times News Service in 1980. “It just seemed like the thing to do.”

A star on the American Legion and high school diamonds as well as in basketball for Memorial High School in Manchester, Mike Flanagan was trending toward a selection in the first few rounds of the 1971 MLB Draft when an arm injury during a Legion game changed the course of his career. He was selected in the 15th round of the draft that year by the Astros but chose college instead, enrolling at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

“Many of the big schools stayed away from him (because of the arm issues), so we ended up getting him,” UMass coach Dick Bergquist told the Daily Hampshire Gazette. “He’s a natural talent, the best I’ve ever had here.”

Flanagan went 9-1 in 1973 for the Minutemen and was drafted again – this time in the seventh round of the June ’73 MLB Draft by the Orioles. He went 4-1 with a 2.21 ERA for Class A Miami of the Florida State League that year then ripped through two levels in 1974, going 12-10 with a 1.97 ERA at Miami and Double-A Asheville in 1974.

The Orioles brought Flanagan to their big league Spring Training camp in Miami in 1975.

“It gives you a lot of confidence,” Flanagan told the Miami News. “Being here gives you an idea how good (major leaguers) are and what you have to do to get into that exclusive class.”

As expected, Flanagan was sent to Triple-A Rochester to begin the 1975 season, and he went 13-4 with a 2.50 ERA in 173 innings for the Red Wings before earning a September call-up to Baltimore. He made his MLB debut on Sept. 5 with 1.2 innings of relief against the Yankees, then started against New York on Sept. 28, working eight innings and earning a hard-luck loss in a 3-2 Baltimore defeat.

Flanagan began the 1976 season in the Orioles bullpen but was 0-3 with a 5.63 ERA in 10 appearances when he was sent back to Triple-A halfway through the campaign. But after going 6-1 in seven starts with Rochester, Flanagan returned to Baltimore in August and joined the rotation, totaling four complete games in his last nine starts to finish the year with a 3-5 record and 4.13 ERA. He pitched for part of the season without signing his contract in the months following the arbitration decision that made Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally free agents but agreed to a three-year deal early in the 1977 season.

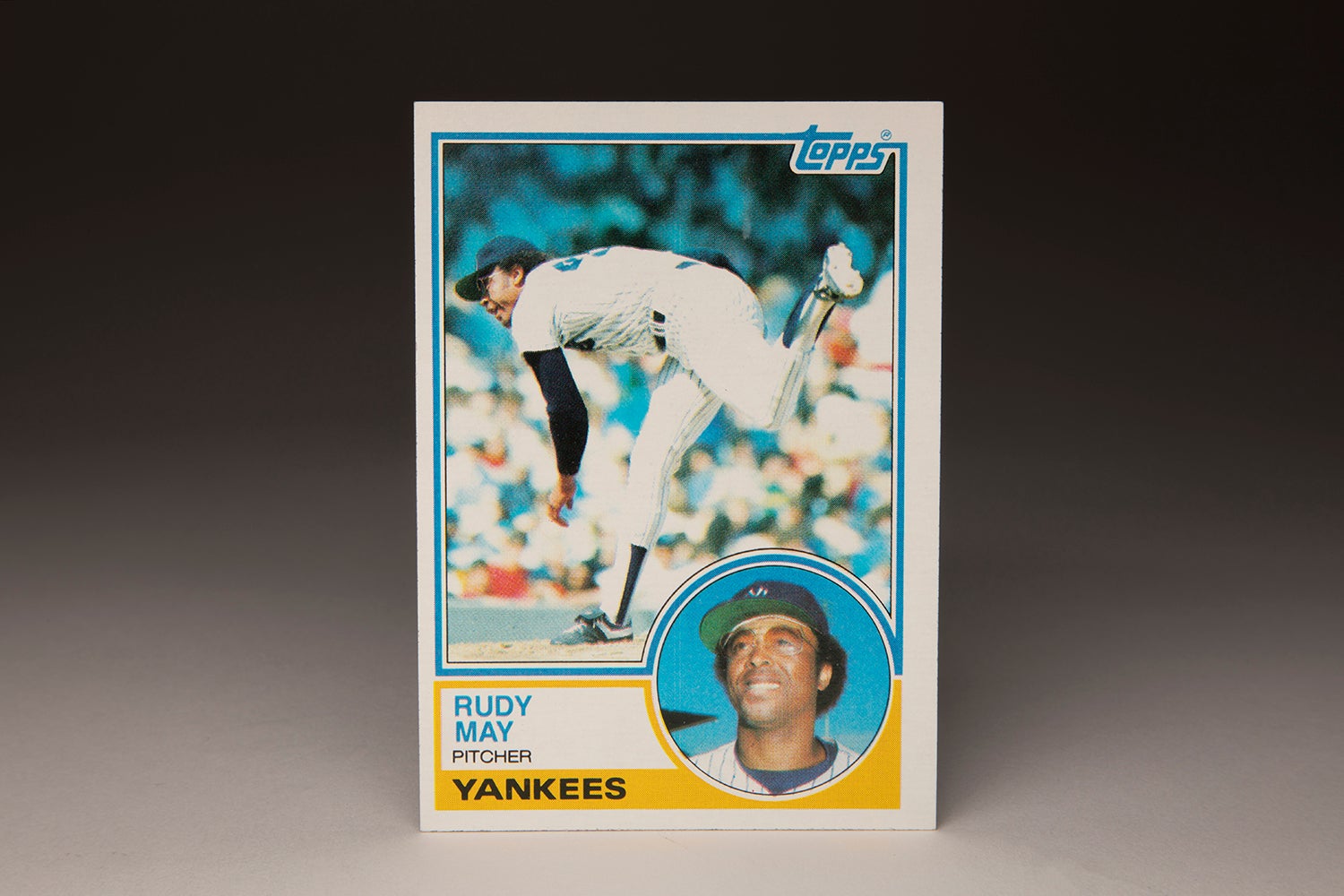

Flanagan remained a starter in 1977, no easy feat given that Baltimore manager Earl Weaver went with a four-man rotation. With early season off days, Weaver turned to Jim Palmer, Rudy May and Ross Grimsley until the team’s ninth game. Flanagan became the team’s fourth starter of the season at that point and worked nine innings, allowing two runs in a matchup against Dennis Eckersley as the Orioles defeated Cleveland 6-5 in 10 innings.

Flanagan would make 36 appearances in 1977 – including 33 starts – while going 15-10 with a 3.64 ERA over 235 innings, including 15 complete games.

“Yeah, there was a time when we had to think about taking him (out of the rotation),” Weaver told the Baltimore Evening Sun midway through the 1977 season. “But I never lost faith in him. I said I’d bet my pocketbook on Mike from the start.”

Weaver’s faith was rewarded as Flanagan became one of the game’s most durable and dependable starters.

In 1978, Flanagan made 40 starts and went 19-15 with a 4.03 ERA in 281.1 innings, earning his first All-Star Game selection. He came within one out of a no-hitter against Cleveland on Sept. 26, surrendering a home run to Gary Alexander and then hits by Ted Cox and Duane Kuiper before Don Stanhouse closed the door on a 3-1 Baltimore victory that gave Flanagan his 19th win of the season.

Heading into 1979, Flanagan perfected a change-up taught to him by teammate Scott McGregor – another Baltimore lefty who relied on location and control.

“It came natural,” Flanagan told the Associated Press, “from the first time he showed me how to throw it.

“After I learned the change-up and threw my slider more, I became a four-pitch pitcher. The change set up my whole gameplan and put me over the hump.”

Flanagan dominated the game in 1979, winning his 10th game before the end of June as the Orioles put it all together on the field. Flanagan was 22-7 after picking up a win over the Blue Jays on Sept. 13 before hard-luck losses in two of his last three games – a period when his ERA dropped from 3.19 to 3.08. But the Orioles coasted to the AL East title, winning 102 games and outdistancing second-place Milwaukee by seven victories.

Weaver turned to Palmer to start Game 1 of the ALCS vs. the Angels, having the luxury of starting Flanagan – who led MLB with 23 wins against only nine losses – in Game 2. Baltimore jumped out to a 9-1 lead after three innings, and Flanagan pitched into the eighth – allowing six runs (four earned) as Stanhouse eventually closed the door on a 9-8 win.

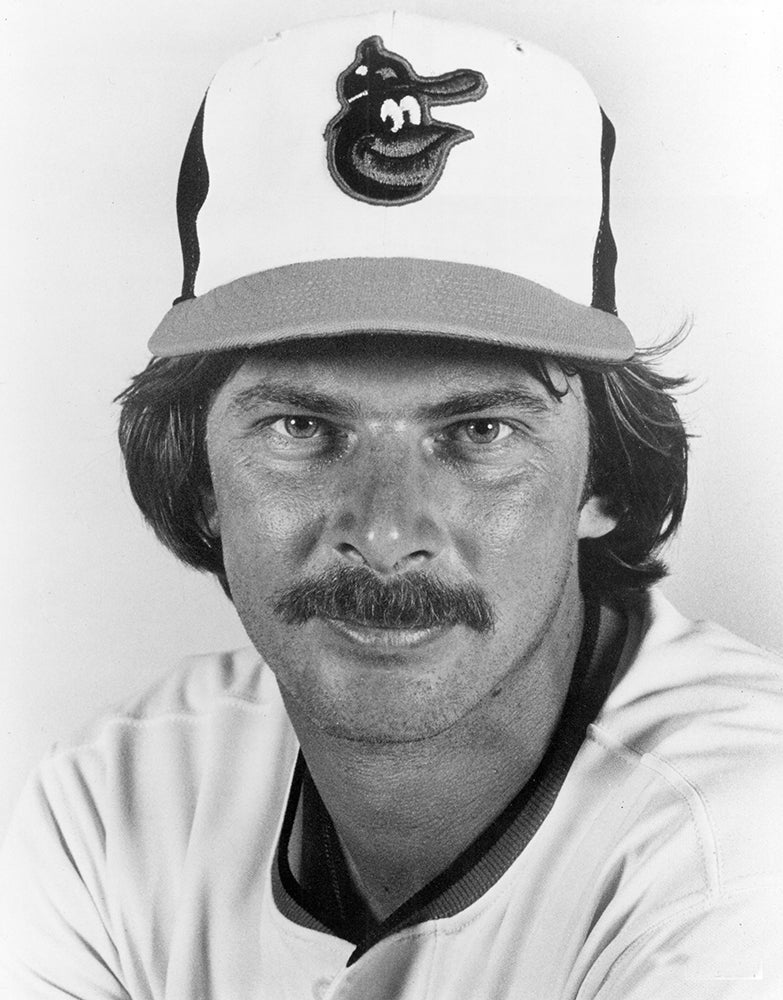

Baltimore won the ALCS in four games to advance to the World Series for the first time since 1971. Weaver chose Flanagan to start Game 1 against the Pirates, and Flanagan allowed just two earned runs in a complete game 5-4 win. Then, with Baltimore leading the series 3-games-to-1, Flanagan went to the mound in Game 5 against Pirates veteran Jim Rooker, who was 4-7 with a 4.60 ERA in 1979.

“The Pirates need a few miracles,” ABC-TV’s Al Michaels told viewers during the pregame segment, “beginning today.”

Rooker outpitched Flanagan, allowing one run over five innings. Flanagan and the Orioles led 1-0 going into the bottom of the sixth before the Pirates rallied for two runs, with the go-ahead score coming on a single by Bill Madlock.

Flanagan, who allowed just the two runs over six innings, took the loss in what became a 7-1 Pittsburgh win.

“Before this game, everything was in Baltimore’s favor,” Pirates second baseman Phil Garner told the Pittsburgh Press. “But Jim Rooker comes in and keeps us in the ballgame against a good pitcher (Flanagan) pitching one of his good games.”

The Pirates won Game 6 to force a deciding game in Baltimore on Oct. 17. Flanagan, having just two days off, was not expected to pitch. But prior to Game 7, Flanagan found his wife, Kathy, unconscious on the bathroom floor, according to a United Press International report. Kathy Flanagan was taken to the hospital and treated for internal bleeding due to an ectopic pregnancy.

Baltimore led 1-0 behind McGregor going into the sixth inning when Willie Stargell’s two-run homer gave Pittsburgh the lead. With the score the same in the top of the ninth, Garner led off with a double against Tim Stoddard and was bunted to third by pitcher Kent Tekulve. Weaver called on Flanagan to face the lefty-hitting Omar Moreno, and Moreno drove home Garner with a single to make the score 3-1. Flanagan was one of five relievers used by Weaver in the ninth inning as the Pirates scored two runs to salt away a 4-1 win.

“That was the hardest time I’ve ever had trying to pitch,” Flanagan told the Associated Press. “I didn’t find out until 10 minutes before the game that my wife was all right.”

Two weeks after the Orioles’ Game 7 defeat, Flanagan was named the AL Cy Young Award winner in a landslide, earning 26 of a possible 28 first-place votes.

“I’ll always look at the award as a team thing,” Flanagan told the AP. “Maybe I was the best pitcher. But I was also on the best team.”

In November, Manchester proclaimed “Mike Flanagan Day” and celebrated with a reception at Memorial High School.

“I was saying to myself: ‘Why me?” Flanagan told the assembled crowd of 1,000 fans. “I’m just the old guy from back home.”

Flanagan went 16-13 with a 4.12 ERA in 1980, allowing an American League-high 278 hits but also helping the Orioles win 100 games (Baltimore fell short in the AL East race to the Yankees).

“(Flanagan) is the same pitcher he was last year,” Weaver told The New York Times News Service. “His curveball isn’t biting as much as it did and he isn’t throwing enough strikes with his breaking stuff, but Mike has had as much back luck as anybody in the league.”

In 1981, Flanagan went 9-6 with a 4.19 ERA in that strike-shortened season. But off the field, the year was a rousing success as Flanagan and his wife found a way to start the family they had always wanted.

On July 9, 1982, Kathy Flanagan gave birth to the couple’s first child – a daughter. The birth made news around the country as the fourth baby born in the United States via in vitro fertilization, known colloquially at the time as a “test-tube baby.” Flanagan pitched in Seattle the night before, allowing four runs over eight innings while being tagged with the loss in a 4-3 Mariners victory. He finished the season 15-11 with a 3.97 ERA – having signed a five-year deal worth a reported $3 million in February.

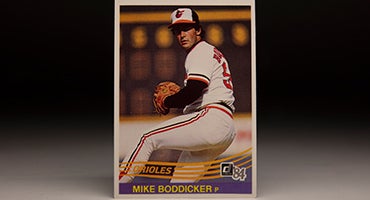

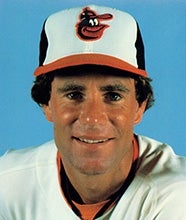

In 1983, a left knee injury forced Flanagan onto the disabled list for almost three months. He was 6-0 with a 2.72 ERA when he was hurt in May, but the Orioles were able to withstand his absence thanks to the work of rookie Mike Boddicker, who went 16-8 with an MLB-best five shutouts as Baltimore won the AL East. Flanagan returned in August and finished the year with a 12-4 record and 3.30 ERA in 20 starts.

Flanagan started Game 3 of the ALCS vs. the White Sox and allowed just one run over five innings, picking up the victory in Baltimore’s 11-1 win. The Orioles advanced to the World Series with a victory in Game 4, and Flanagan started Game 3 of the Fall Classic against the Phillies with the series tied at a game apiece.

Wearing a brace on his left knee, Flanagan allowed two runs over four innings before being relieved by Palmer with the Phillies leading 2-0. Baltimore rallied for a run in the sixth and two in the seventh to win 3-2 – giving Palmer the victory and making him the first pitcher in history with World Series wins in three different decades.

Baltimore won the series in five games to give Flanagan his first World Series ring.

Flanagan went 13-13 in 226.2 innings in 1984 before missing the first three-and-a-half months of the 1985 season with a ruptured Achillies tendon – an injury suffered while he was playing basketball for the Orioles charity team. After making 15 starts down the stretch and posting a 4-5 record, Flanagan was 7-11 with a 4.24 ERA in 1986.

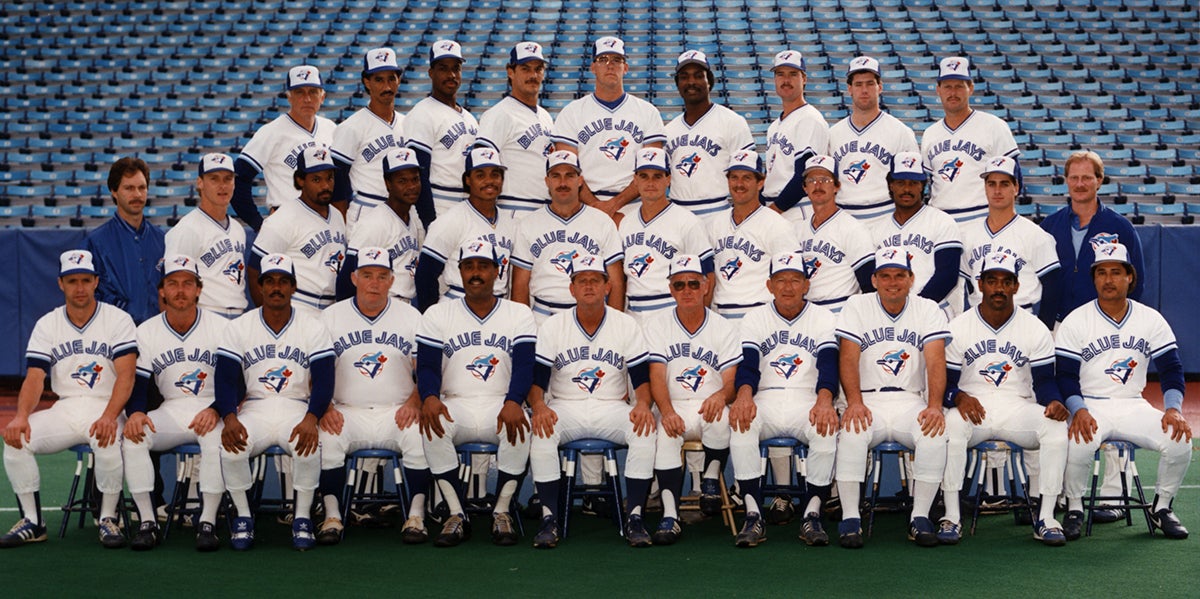

After going 3-6 with a 4.94 ERA in 16 starts for the Orioles in 1987, Flanagan was traded to the Blue Jays on Aug. 31 in exchange for Oswaldo Peraza and a player to be named later who turned out to be future All-Star closer José Mesa. As part of the deal, the Blue Jays extended Flanagan’s contract through the 1988 season – a condition necessary for Flanagan to waive his no-trade rights as a 10-and-5 player.

“I really don’t think you’re ever prepared for things like that to happen like this,” Flanagan told the Evening Sun. “I wish the (Orioles) nothing but the best. I’ll always be an Oriole.”

Flanagan went 3-2 with a 2.37 ERA in seven starts for Toronto, but the Blue Jays were unable to hold a late-season lead in the standings against the Tigers. On the next-to-last day of the season – with the teams tied at 96-64 entering the game – Flanagan allowed just two runs over 11 innings but was lifted with the game still tied.

In the bottom of the 12th, Detroit pushed across a run against Jeff Musselman and Mark Eichhorn to win 3-2, and the Tigers won the next day to clinch the AL East title.

“The game had a heartbeat all its own,” Flanagan told the Los Angeles Times. “From the third or fourth inning on, I was in a groove where I was throwing the ball wherever I wanted it.”

Flanagan went 13-13 with a 4.18 ERA in 211 innings in 1988, then re-signed with Toronto following the season. The Blue Jays won the AL East title in 1989, and Flanagan proved to be an effective back-of-the-rotation starter, going 8-10 with a 3.93 ERA. He made the final postseason appearance of his career in Game 4 of the ALCS vs. Oakland, allowing five runs over 4.1 innings while taking the loss in a 6-5 Athletics victory. Oakland won the series in five games.

After going 2-2 with a 5.31 ERA in five starts in 1990, Flanagan was released by the Blue Jays on May 8.

“There are only two sure things in this game,” Flanagan told the Canadian Press. “You’re either going to quit or get released.”

Flanagan did not pitch for the rest of 1990 but returned to the Orioles in 1991 as a reliever, earning a spot as a non-roster invitee to Spring Training and going 2-7 with a 2.38 ERA and three saves in 64 games. But he struggled to reprise that success in 1992, posting an 8.05 ERA over 42 games out of the bullpen. It would be Flanagan’s last season as a pitcher.

In 1994, Flanagan joined the Orioles’ broadcast team, then moved back to the playing field in 1995 as the team’s pitching coach. He lost that job when Davey Johnson took over as Orioles manager in 1996 but returned as pitching coach for Baltimore in 1998 under new manager Ray Miller.

After returning to the Baltimore broadcast booth from 1999-2002, Flanagan was named the Orioles co-vice president of baseball operations. He remained in the team’s front office through 2008 and then soon returned to the broadcast team.

On Aug. 24, 2011, Flanagan’s body was found about 100 yards behind his Baltimore-area home. Authorities ruled he had committed suicide.

“He was a great player, a pitching coach, a general manager, a broadcaster,” Jim Duquette, who worked with Flanagan in the Orioles’ front office, told The Boston Globe. “He did so many things and he did them well. This was an exceptional individual in every facet of his life.”

Over 18 big league seasons as a pitcher, Flanagan was 167-143 with a 3.90 ERA.

In 2014, the City of Manchester named a baseball field adjacent to his old high school “Mike Flanagan Field” in honor of the former two-sport star at Memorial High School.

“Our family is so thankful and honored,” Ed Flanagan told the Manchester Union Leader. “I had feared Mike’s name might be forgotten.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum