- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Ken Hubbs’ history alive in Cooperstown

#Shortstops: Ken Hubbs’ history alive in Cooperstown

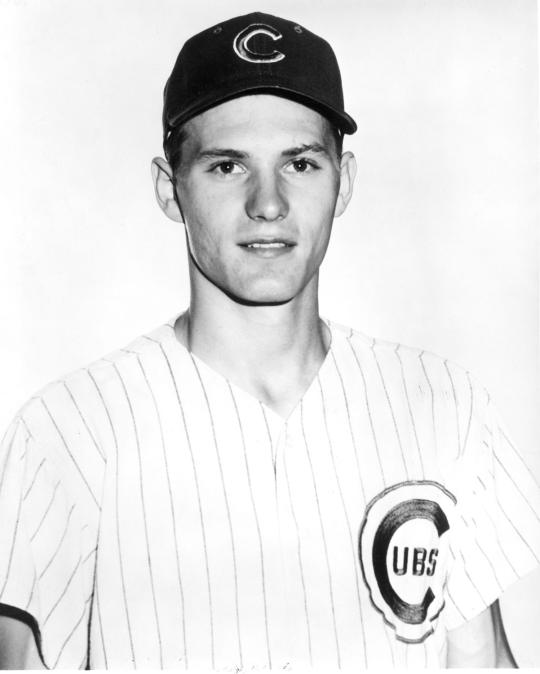

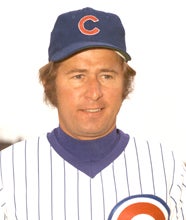

Ken Hubbs, a sure-handed second baseman with the Chicago Cubs, was only 22 when he died in a plane crash in 1964, one of the most tragic events in baseball history.

Four decades later, a pair of record-setting items from his short but significant career call Cooperstown home.

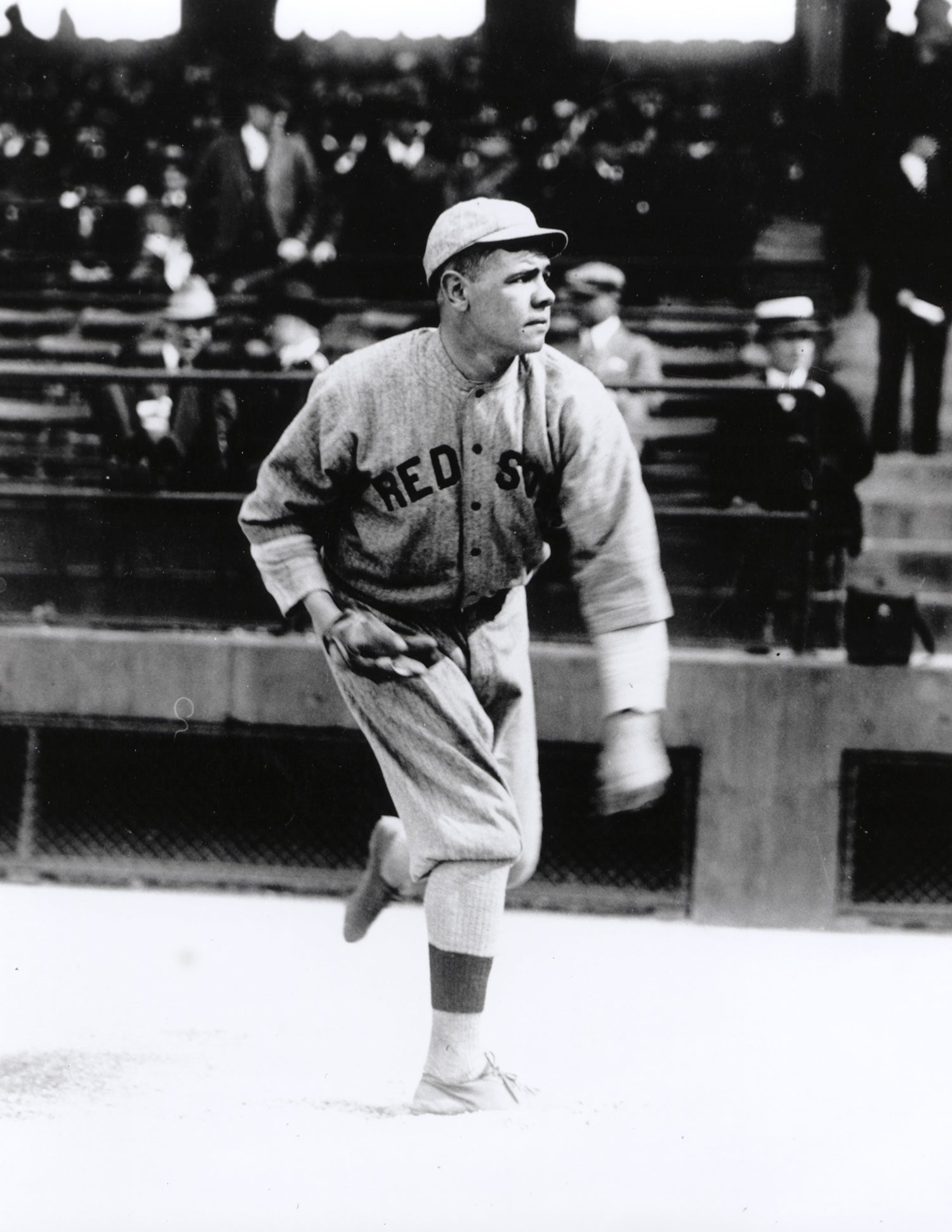

Hubbs, a multisport athlete from Colton, Calif., made his big league debut at 19 with the Cubs in September 1961. By the next season, he was entrenched as the starting second baseman, part of a nucleus that included such future Hall of Famers as Ernie Banks, Ron Santo, Billy Williams and Lou Brock.

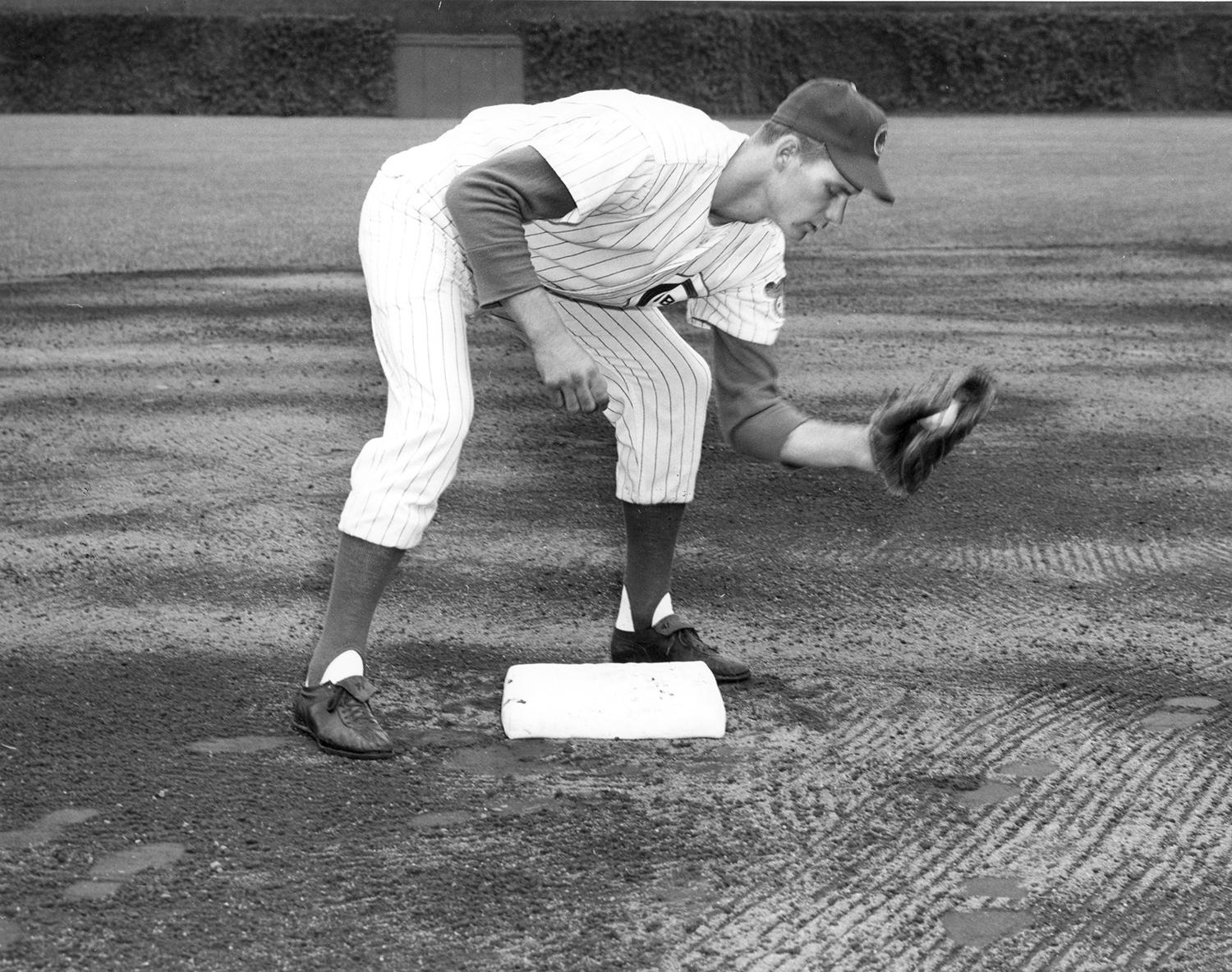

Though Hubbs, 6-foot-2 and sandy haired, batted only .260 with five home runs and 49 RBI in 1962, his defensive prowess at the keystone sack not only helped him become the first rookie to capture a Gold Glove Award, but also the Senior Circuit’s Rookie of the Year honors.

Most memorable during that ‘62 campaign was Hubbs setting two major league records by playing more consecutive errorless games (78) and handling more consecutive chances (418) than any second baseman in history. Today, Placido Polanco of the Tigers holds these major league records with 911 consecutive errorless chances over 186 consecutive errorless games during a three-season stretch from 2006-08.

“I’m sure glad that’s over with,” said the 20-year-old fielding flash when the streak came to an end with an error on Sept. 5, 1962. “It was sort of like waiting for the other shoe to drop. Now I finally can concentrate on my hitting. Boy, I wasn’t thinking at all at bat during the last few weeks.

“I was happy to break the record and I’m glad it’s all over. Now I can go back to playing second base again.”

In the offseason after a solid 1963 season, though, the Hubbs story came to a devastating end. Along with hometown friend Dennis Doyle, the duo took off from a Provo, Utah, airport on Hubbs’ new Cessna 172 headed for Colton. Hubbs, who would often sit in the cockpit on the Cubs chartered flights, first began flying small planes at Mesa, Ariz., where the Cubs held Spring Training.

With Hubbs piloting, the two left the on their ill-fated flight on a snowy Feb. 13, their bodies found in the wreckage of the plane two days later. It had crashed onto the ice of Utah Lake, five miles away from Provo.

“Every time the front door opens, I expect to see Ken walking through, wondering what’s going on,” said Hubbs’ father, Eulis, a few days after the crash. “Part of me just doesn’t believe it. For a long time, I’m going to be looking for his name in the Cubs’ box scores.”

Hubbs’ funeral would take place in Colton on Feb. 20, 1964, with reports estimating 2,000 mourning the local athletic hero. Cubs teammates acting as pallbearers included Glen Hobbie, Don Elston, Dick Ellsworth, Santo and Banks, along with manager Bob Kennedy.

“Ken and I were both religious,” said Santo in a 1964 interview. “We were always joking – trying to convert each other. I’m Catholic, he was a Mormon. But after he died, I had to see a priest. I couldn’t understand it. I mean, he loved life. He was a great human being. This was a kid who didn’t even smoke or drink. Why him?”

“At the time he died, I definitely felt he was on his way to a Hall of Fame career,” said Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau, who was a Cubs broadcaster when Hubbs came up to the majors. “His bat hadn’t come around, but it would have. He was a contact hitter.”

Keith Hubbs, Ken’s older brother, recalled in a 1993 interview with the Los Angeles Times what the days were like after the horrific news.

“Several days after we learned he died, the doctor came to my folks’ house, to give them sedatives so they could sleep,” Keith Hubbs said. “I didn’t want to sleep. I was having terrible nightmares about Kenny. Every night, it was a variation of the same dream – I’d dream I was in that plane with him, that we were going down together.

“Then one night I dreamed he was standing right in front of me. Clear as anything. And he said to me: ‘Don’t be concerned about this. It was quick, not at all painful. And I’m very happy where I am.’ That was almost 30 years ago. And I’ve never dreamed about him since.” In a later interview, Keith Hubbs said he had reservations about his brother’s flying.

“I didn’t like it, and neither did Dad,” said Keith Hubbs. “Dad had a long talk with him about it. But Kenny was a very mature kid, so Dad let him go. I was in Mesa the summer before he died and I told him I didn’t like the idea of him flying, either. But he had a certain way about him – he could convince you that you should try anything. The next thing I knew, he’s introducing me to his flight instructor and then I’m taking flying lessons.”

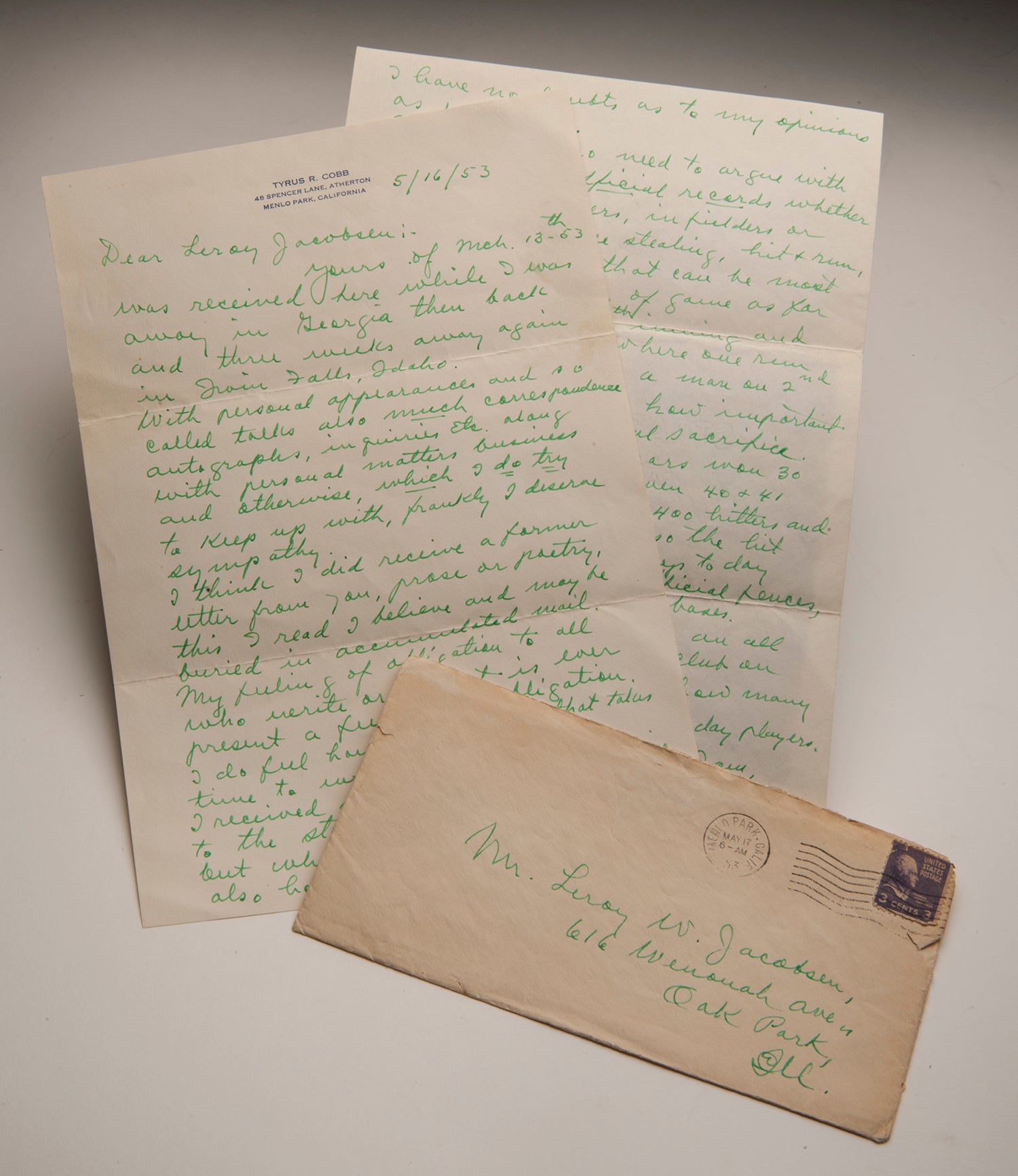

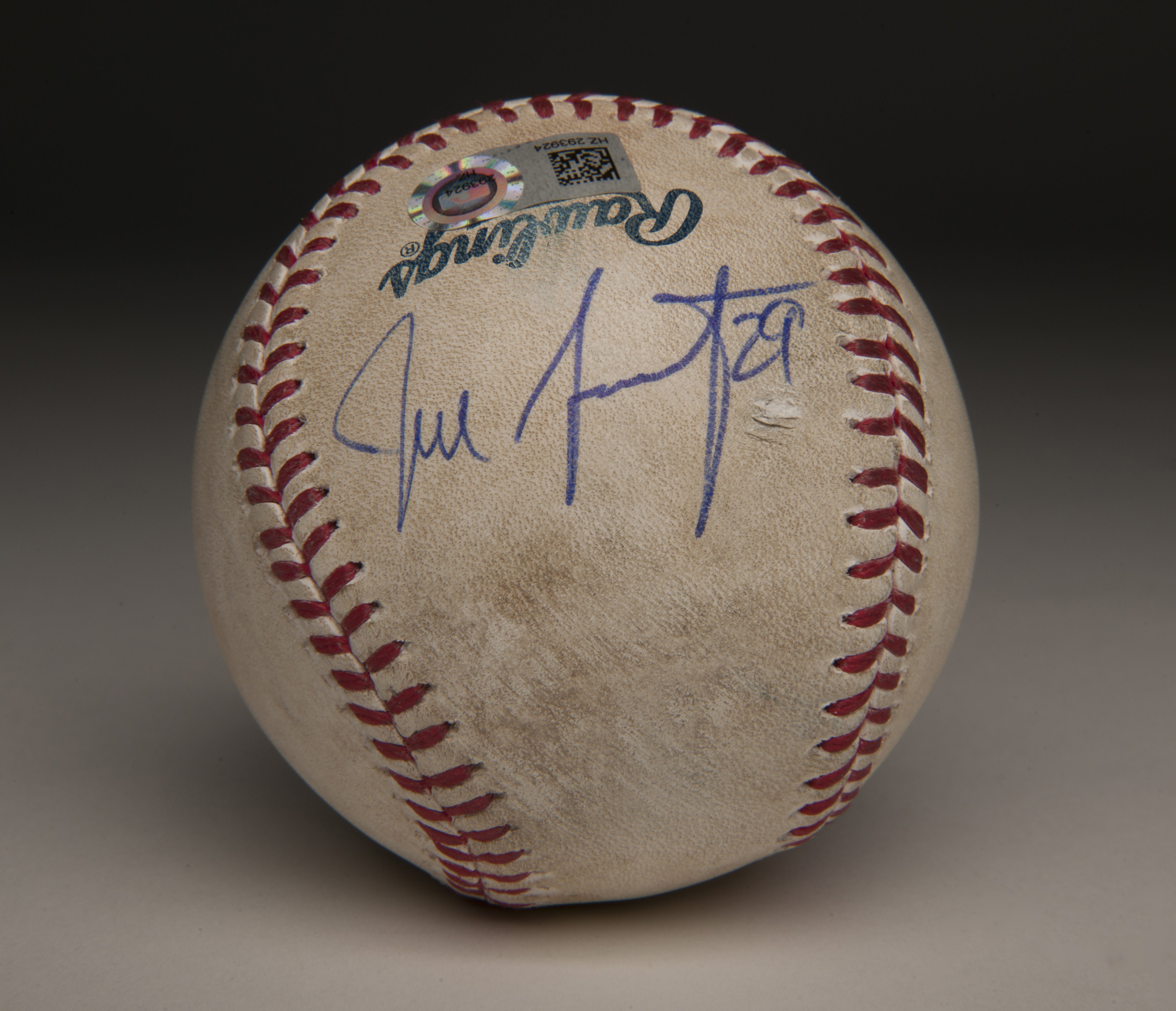

Fast forward to 2003 and Keith Hubbs is serving a Mormon mission in Chicago. That season’s All-Star Game was being held at U.S. Cellular Field, home of the White Sox. Quite by chance, Hubbs had recently come across the baseball from Hubbs’ 74th consecutive errorless game on Sept. 2, 1962, which broke Bobby Doerr's record at that position. Soon after, his mother remembered she had the glove Hubbs used during that record-breaking season, a Spalding Chuck Cottier E-Z model.

Keith Hubbs was soon presenting the two artifacts to Baseball Hall of Fame Chief Curator Ted Spencer, who was in Chicago setting up the Hall of Fame’s exhibit for FanFest in conjunction with the All-Star Game. Soon enough, the glove and baseball were on display at FanFest and later taken to Cooperstown as a donation.

“It’s nice to have just a little bit of him in the Hall of Fame,” Keith Hubbs said. “It’s better [for it] to be preserved for generations to come.”

“It's a great story for baseball, how the teams and players are ingrained in the life of a city," Spencer said. “Ken Hubbs was in town only two years, and 40 years later his impact is still felt.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum