- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: The feverish story of yellow baseballs

#Shortstops: The feverish story of yellow baseballs

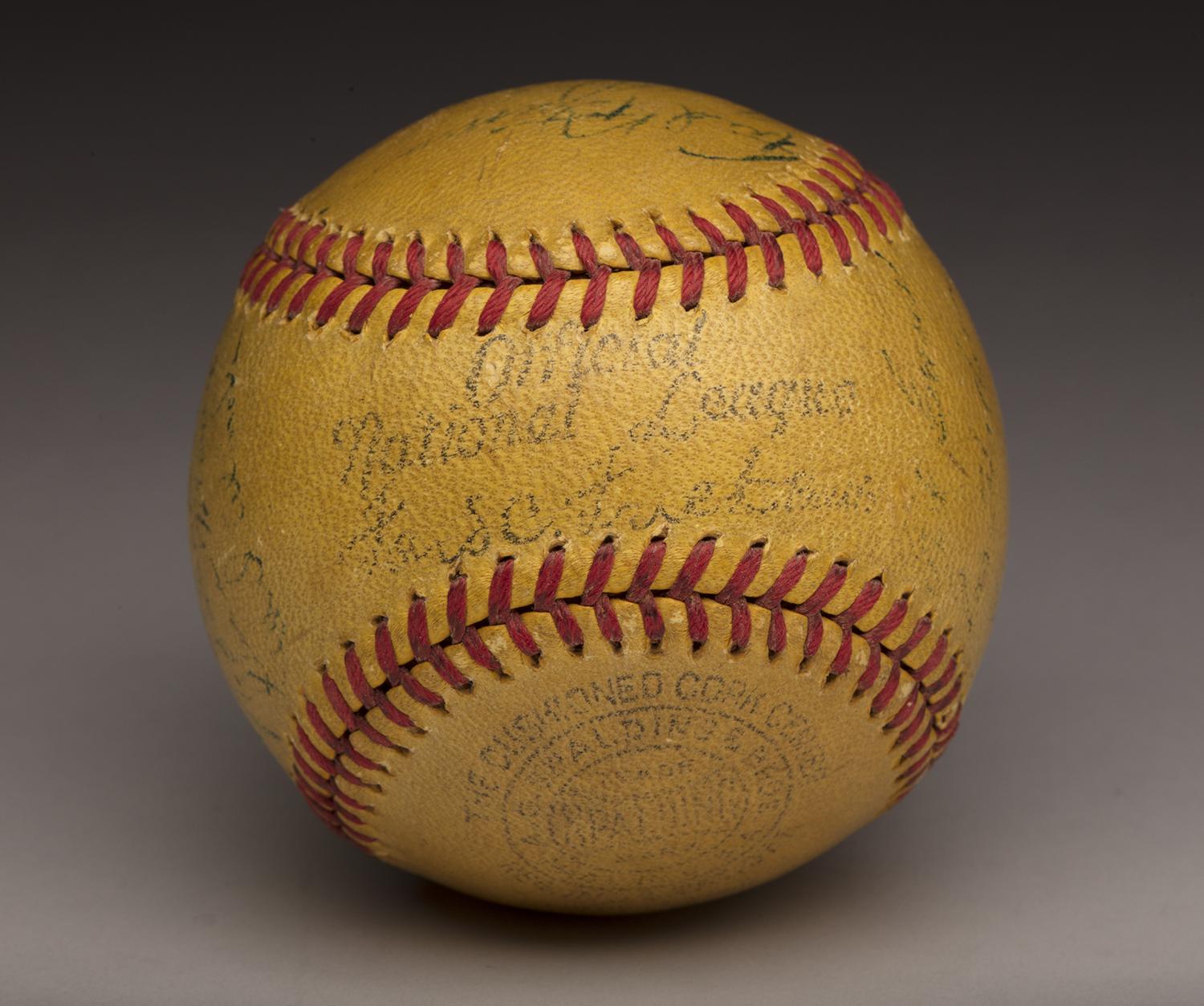

An experimental, high-visibility yellow baseball, tagged with such unique monikers as a “stitched lemon” or “canary-colored horsehide”, made a noteworthy but short-lived appearance when it was used in the big leagues in the late 1930s.

Recently, one of these rare balls with its own unique backstory was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Though fans may recall that the Oakland A’s, under maverick owner Charles Finley, used orange baseballs in a 1973 exhibition against the Indians, they may not know that the use of another non-white ball appeared more than three decades earlier.

In 1938, newspapers across the country published eye-catching reports of the big leagues exploring the use of a yellow baseball instead of the conventional white. The Brooklyn Dodgers, led by the dynamic and innovative mind of front office executive Larry MacPhail, were at the forefront of this novel move. In mid-July, it was announced that on Aug. 2, in the first game of a doubleheader between the host Dodgers and Cardinals at Ebbets Field, the teams would buck tradition and give this newly dyed orb a shot.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The impetus for this new yellow ball came from New York color engineer Frederic H. Rahr, who developed it after Mickey Cochrane was severely beaned by a pitcher the previous season.

“My primary object is to give the hitter more safety and there’s no question that this will be achieved,” said Rahr in an April 1938 interview. “That’s simply because the batter will be striking at a ball he can see instead of at a white object that blurs with the background. We have known for a long time that yellow was the most quickly and clearly seen of all colors, especially at high speed. That’s why traffic markers, airport markings and government specifications, where protecting human life is essential, are invariably in yellow. On the other hand, white is probably the most difficult of all colors to see in motion.

“The yellow ball should do more than provide safety. There’ll be more hitting – not longer hitting, perhaps, but more hitting. I see no reason now why a left-handed hitter won’t be fully effective against a left-handed pitcher and a right-handed batter against a right-handed moundsman. The ball won’t blur against the white or gray uniform of the pitcher,” Rahr added. “The fielding should be sharper because the ball will be more visible on the ground and in the air. The umpires will do better on balls and strikes because they’ll be able to see the ball more clearly. The spectators will be able to follow fast fielding double plays and quick decisions at the bases.”

Several college games experimented with the use of the yellow ball in the spring of 1938, including the initial contest between Columbia and Fordham on April 27, 1938. Columbia coach Andy Coakley, a big league pitcher for nine seasons, said afterward that one contest was hardly enough to settle its value, but that an entire series of games probably would be necessary.

After MacPhail had gotten the new yellow ball, with its familiar red stitches, sanctioned by National League President Ford Frick, he said, “We want to find out whether the scientists know what they’re talking about.”

Before an announced Ebbets Field audience of 18,567 - the largest weekday crowd of the season – the Dodgers defeated the Cardinals, 6-2, using the yellow ball in the first game of the doubleheader on Aug. 2, 1938. Slugging Cardinals Hall of Fame first baseman Johnny Mize hit the contest’s only homer. Brooklyn also took the second game, this time using the white ball, 9-3.

According to The New York Times, “A majority of the players and fans were in favor of the yellow ball, voicing the opinion that it could be followed in flight much better.”

“I could follow it well enough from the bench,” said Brooklyn manager Burleigh Grimes. “I really think it would be a good ball to use against a white-shirted background, such as the one in Chicago’s Wrigley Field.”

Prior to the game, a confused Cardinals manager Frankie Frisch claimed he thought the new yellow balls would be first used the next day.

“Oh, what the hell, try them out now,” Frisch said. “The way my players are hitting nowadays, it doesn’t make any difference whether they use yellow balls, white balls, or red, white and blue balls.”

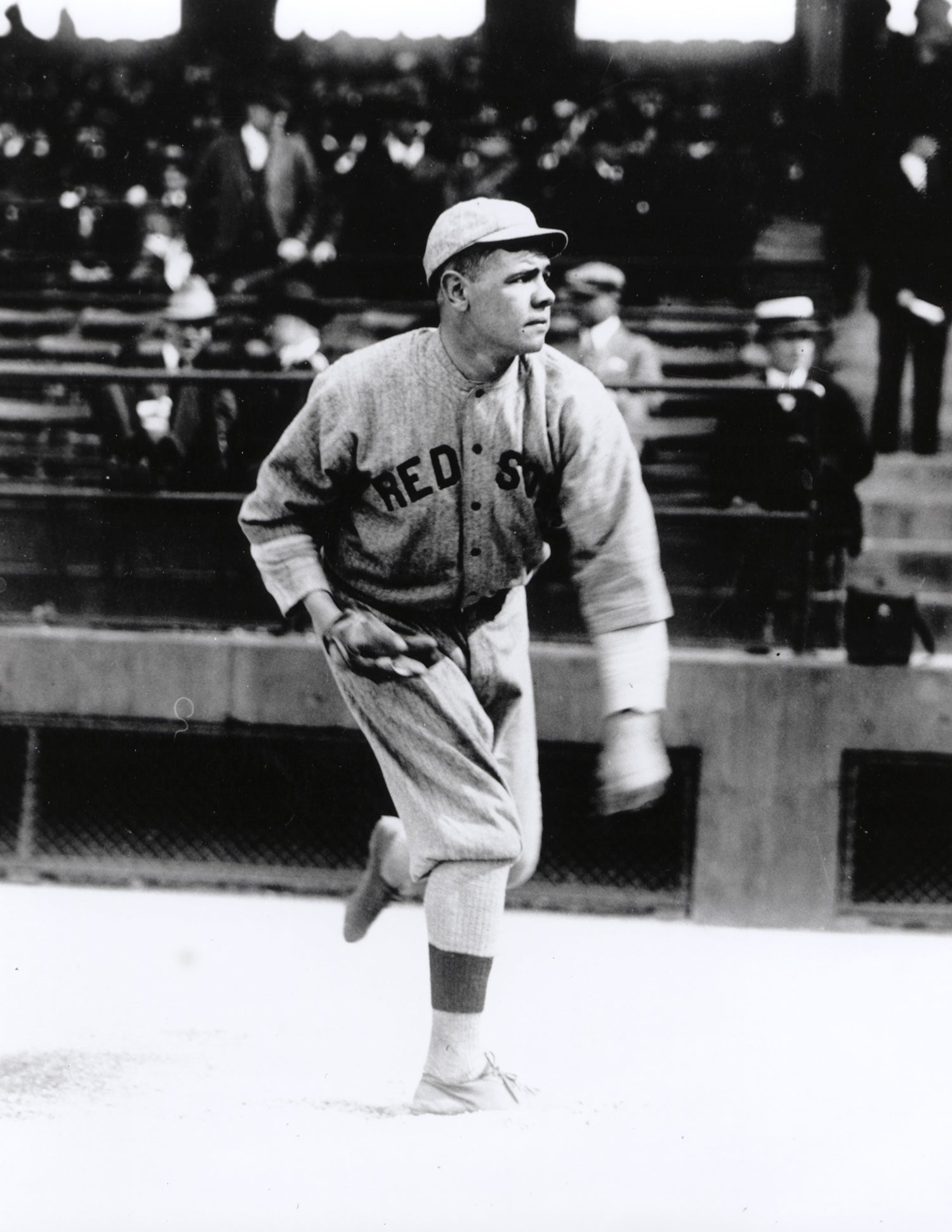

The immortal Babe Ruth, named a Dodgers coach in 1938, asked, “What’s the difference? They’re all round. I hit three over the fence in practice. It all depends on who’s throwin’ it atcha.

“I didn’t even know it was yellow until somebody fouled one down there by me. The color don’t make no difference. It’s the guy who who’s chucking ‘em at you that counts. When a good pitcher is throwing that ball, they all look like aspirin tablets.”

Dodgers righty Freddie Fitzsimmons, who tossed a complete game for the win with the yellow ball, had one major complaint and it resulted in the entire side of his uniform stained yellow where he had to wipe is hand off. “It was just about as good as any white ball, except that the yellow dye was coming off my sweaty hands and it made my hands sticky.”

Concerning Fitzsimmons’ issue, Rahr said, “We’ve had chemists working for months trying to find a dye that would withstand perspiration and still not be oily, but so far they haven’t hit on it.”

Cardinals left fielder Joe Medwick, the reigning National League MVP, got only one hit, a single, but did not blame the yellow ball. “When you’re bangin’ ‘em, even a ‘nickel rocket’ will go for a base hit. I clouted the yellow ball all over the lot in an exhibition last night, but couldn’t get one out of the infield today.”

Umpire George Barr, who worked behind the plate, said, “I didn’t see much difference. I’d prefer to withhold comment until I have a chance to see the experiment against a white background.”

Dodgers shortstop Leo Durocher joked, “When you hit the way I do, they can throw a red ball, a green ball, or a fancy dress ball, even, and it doesn’t make any difference. I can miss any and all kinds.”

MacPhail was reserving judgement.

“We haven’t any opinion for or against the yellow ball,” he said. “However, most players with whom I have talked with think the yellow ball might prevent accidents like the one that ended Mickey Cochrane’s playing career.”

On Aug. 3, 1938, the day after the yellow ball was first used in the majors, New York City newspaper advertisements appeared for Gimbels, a department store located at 33rd and Broadway, promoting the fact that they are selling both white and yellow baseballs. The yellow baseballs were selling for $1.59.

“People who go in for yellow baseballs are in the minority, it’s true,” the Gimbels ad read. “But to Gimbels the minority is just as important as the majority! We believe in serving EVERY group (no matter how small), and in stocking EVERY item (no matter how unusual) to give you – throughout the store – the thing you want, in the size you want, in the color you want, every day of the year!”

On Aug. 11, 1938, the Sporting News, the then self-described “Base Ball Paper of the World” editorialized, “Though the ball cannot be regarded as a complete success at present, especially in view of such a limited test, enough favorable evidence was adduced to warrant a continuation of the experiment. Anything that contributes to greater safety in the game merits a thorough trial, and on this basis alone, the tests should be continued until the ball’s usefulness and practicality can be definitely established or disproved.”

In December 1938, the National League voted to permit use of the yellow baseball as long as opposing managers agree to the use of the ball before such games.

Unfortunately for its proponents, the yellow baseball made only a few more appearances in major league action, once more in 1938 and a couple times in 1939.

Luckily for the Hall of Fame, the first yellow ball used in a major league game on Aug. 2, 1938 was donated to the Cooperstown institution in 1939. Signatures on the yellow baseball include those of Frick, MacPhail, Cardinals president Sam Breadon, Grimes, and inventor Rahr. Another yellow baseball was donated to the Hall of Fame in 1969.

Though MacPhail, in a Brooklyn Eagle interview that appeared on July 29, 1940, lauded the yellow ball and said that he had plans to revive its use, this unique piece of baseball equipment never appeared again at the sport’s highest level.

“The yellow ball,” said MacPhail, “hasn’t received anything like the trial it deserves. What I’ve seen of it, I approve. Forced to judge on the few trials I’ve watched, I’d have to admit that it is far superior to the white baseball now in use.

“Our reason for not carrying on the experiment,” he added, “has been the fact that until last week the Dodgers were fighting for first place. If we had tried the yellow ball and things had gone wrong the innovation would have been blamed as sure as shooting.

“It may be that a yellow ball is the best possible type of baseball. I’m rather inclined to think it is. I’m sure it ought to be obligatory for games at Wrigley Field, where the hitting background of white shirts in the center field bleachers is enough to drive a visiting batter dippy.”

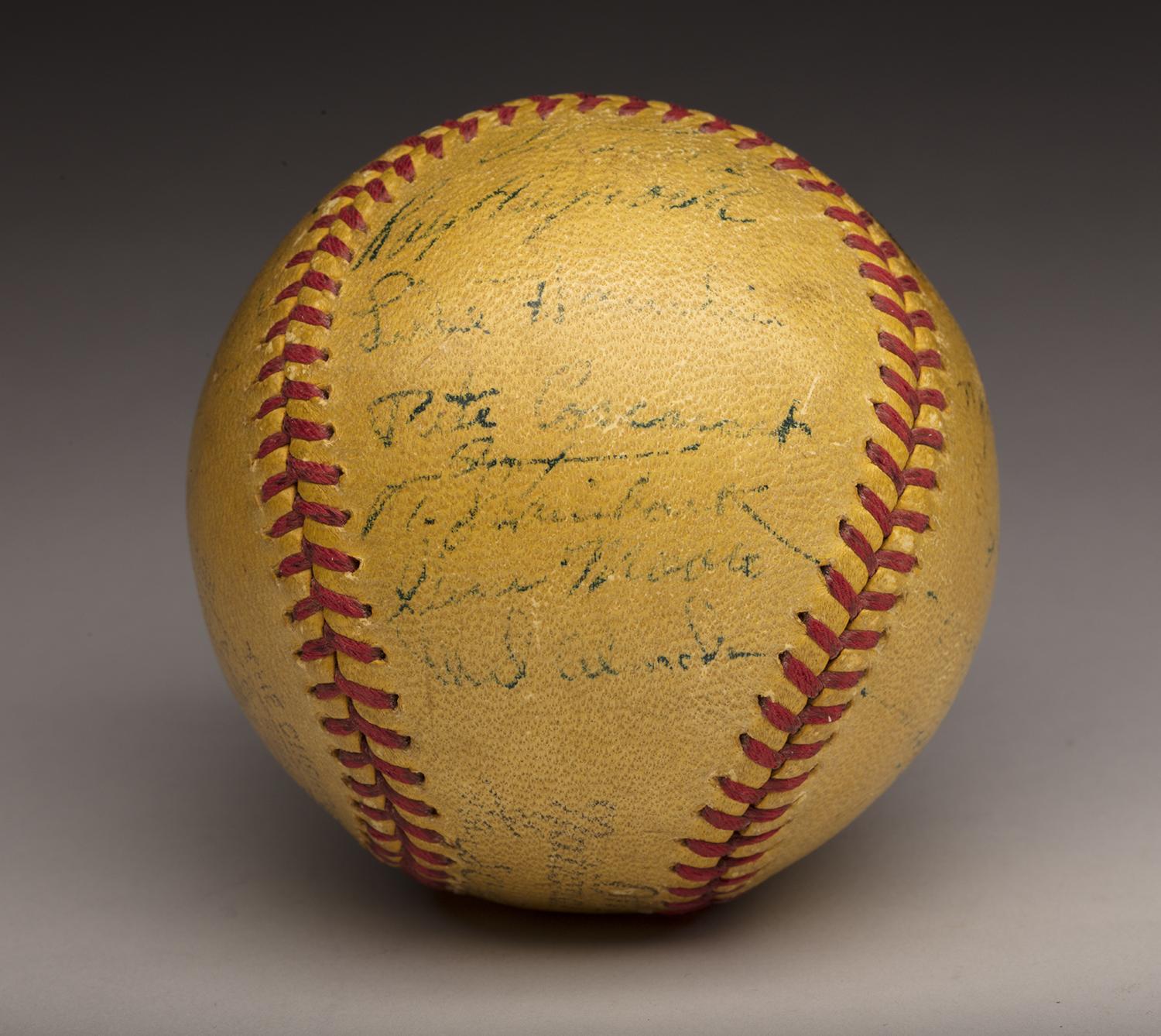

In 2017, Virginia’s Corrine Thompson generously donated to the Hall of Fame a 1939 yellow baseball signed by members of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Family history has it that Thompson’s grandmother, Estelle Hensley, caught the foul ball at Ebbets Field. The signatures were gathered after the game by simply going to the first row of stadium seats by the dugout, and making the request. One of the players requested that Hensley wait while he went down to locker room to get the ball signed.

According to Thompson, her father believed it was a unique item more at home in the Hall of Fame for public display than in some private collection.

“In regard to our thoughts about the donation, our dad, a product of Brooklyn in its mid-20th century heyday, spent countless days at Ebbets Field as a kid,” Thompson wrote in an email. “He talked constantly about the times he was there, various games, and how central the ballpark was to the life and times of his youth, and that of his friends and family. So when we think of Ebbets Field, we think of our dad and all of the great times he enjoyed not just inside, but playing stickball and all the other games he and other kids played just blocks away in a neighborhood that truly exuded the concept of an American cultural melting pot.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum