- Home

- Our Stories

- The game stays the same even as baseballs change

The game stays the same even as baseballs change

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has approximately 10,000 baseballs in its collection, each with its own story.

But though they may look similar on the surface, the makeup of those balls has changed throughout history.

In 2021, big league baseballs were to be deadened slightly to lessen a historic power surge the game has recently witnessed. This development harkens back to a period more than eight decades ago when the National Pastime made a similar attempt to remove the “rabbit” from the ball.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

According to Major League Baseball’s official rules, “The ball shall be a sphere formed by yarn wound around a small core of cork, rubber or similar material, covered with two strips of white horsehide or cowhide, tightly stitched together. It shall weigh not less than five nor more than 5¼ ounces avoirdupois (based on 16 ounces in a pound) and measure not less than nine nor more than 9¼ inches in circumference.”

In February 2021, The Athletic, reported on the contents of a MLB memo that stated it would be subtly deadening its official Rawlings baseballs – in part by loosening the tension on the first of three wool windings within the ball – with lab reports stating the new balls would fly one to two feet shorter on balls hit over 375 feet.

Prior to the pandemic-shortened 2020 campaign, a record 6,776 homers were hit during the 2019 regular season.

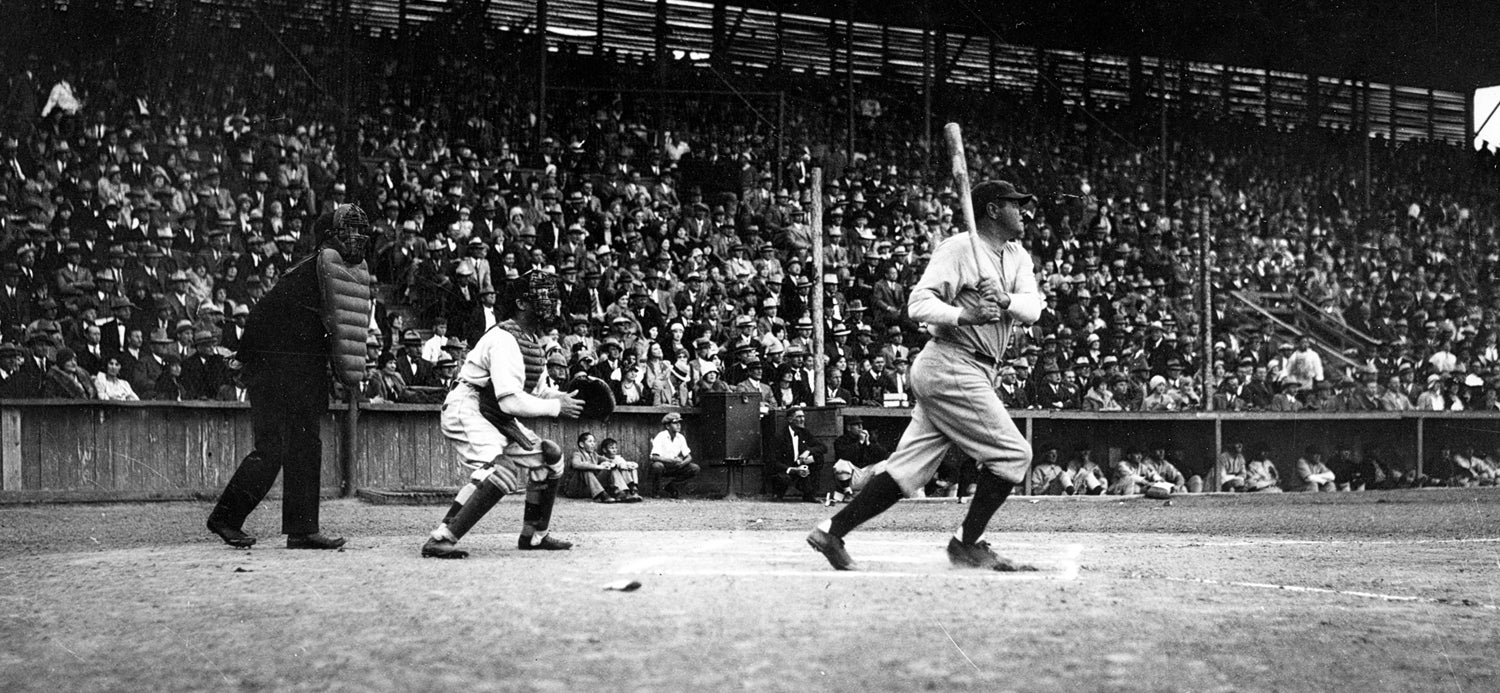

In baseball parlance, the dead ball era is generally considered the first two decades of the 20th century, when hitting behind runners, stealing bases and swatting the ball in the outfield gaps was the rage. This all changed during the roaring ’20s with Babe Ruth’s arrival.

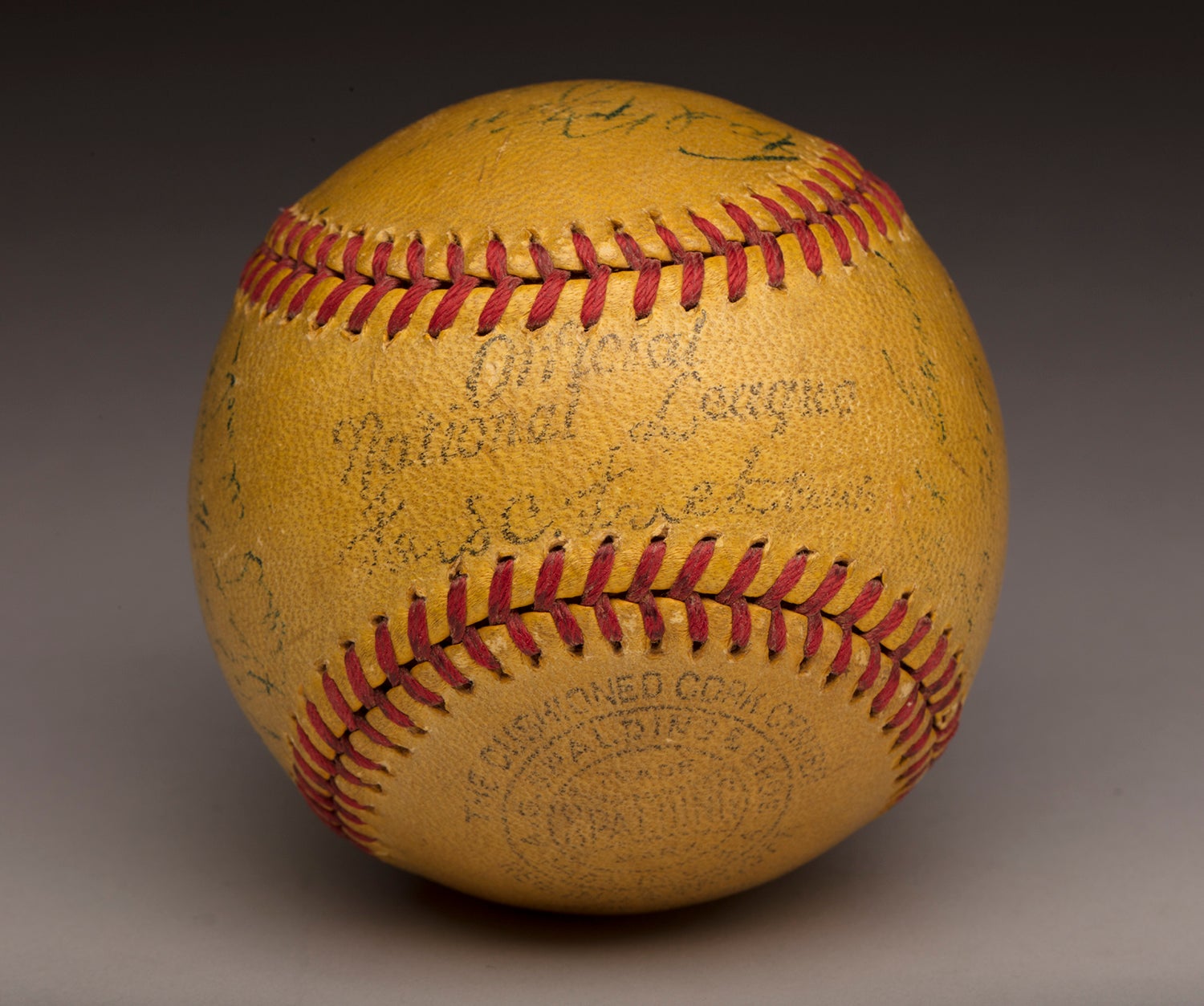

It was during the 1920s when the majors publicly introduced a livelier ball that raised offensive numbers across the board. This ultimately led to a 1930 season in which the 16 major league teams combined to set 20th century marks with a .296 batting average and 1,565 home runs.

The offensive explosion caused concern among a number of the sport’s leaders, and change was soon on the horizon. The result saw diverging opinions among the two circuits – the American in 1931 remaining with the same baseball while the National League deadened its sphere.

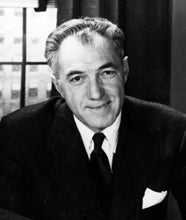

NL President John Heydler, in a February 1931 article in the New York Herald Tribune, tried to put the changes in the ball in context.

“It is virtually the same ball it always has been,” he said. “Back in 1910 a cork center was substituted for rubber. Later small braces were introduced to hold the core in its proper place. The dimensions, weight and general construction of the ball have been the same since 1876, when the National League was started.

“Now we have made a slight change. I anticipate that the players will find fault with it as soon as they start spring training. They will insist that they cannot drive it as they could the old-style ball. But don’t pay any attention to them. They never start hitting in spring training anyway. We won’t know definitely what the effect of the changes will be until the middle of July.”

Sports columnist Westbrook Pegler wrote in August 1931 of the differing points of view regarding the ball’s construction – especially the AL’s high regard for the long ball.

“The National League, it may be remembered, adopted not only the raised stitch for the seams but a slightly thicker cover. The stitches were intended as handles, of a sort, to favor the pitchers in the performance of their art, and the increase in the hide to soften the blow to the sensitive nervous system of the ball.

“The American League adopted the raised stitch, but the American League was more in debt to the home run, and particularly to Babe Ruth’s home runs, for its prosperity. So the heavier cover was not adopted there. If the hitters could get hold of the new ball in the course of the more abrupt hops attributable to the stitching, the ball would still travel as before.”

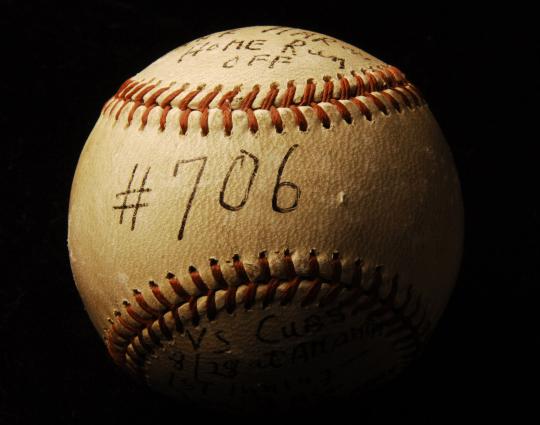

Hank Aaron hit this baseball for his 706th career home run on Aug. 28, 1973. Offensive totals in the 1970s were depressed in both the American League and National League, causing some to advocate for the balls to be "enlivened" and spurring the AL to adopt the designated hitter. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

The results from the 1931 season showed the NL hitters finished with a .277 batting average and 493 homers, compared to a .303 batting average and 892 homers in ’30. In the Junior Circuit, 1931 results league-wide saw a .279 batting average and 576 homers as opposed to a .288 batting average and 673 homers in 1930.

After the 1931 season was over, Heydler – excited that his circuit’s St. Louis Cardinals had captured the World Series – told The Christian Science Monitor that baseball was back where it was a dozen years ago.

“I didn’t have any idea what we were doing to the game,” Heydler admitted. “All we did was have them add about a paper thickness of leather and bind the ball with four strands of thread instead of three. Of course, we thought it might make a slight difference in favor of the pitchers, but we didn’t foresee it would change the whole game and give us our first championship since 1926. That’s what it did, though. The Cardinals realized what had been done. They adopted themselves to that new ball quicker than the other clubs, based their attack and defense on it, and fought their way to the title.

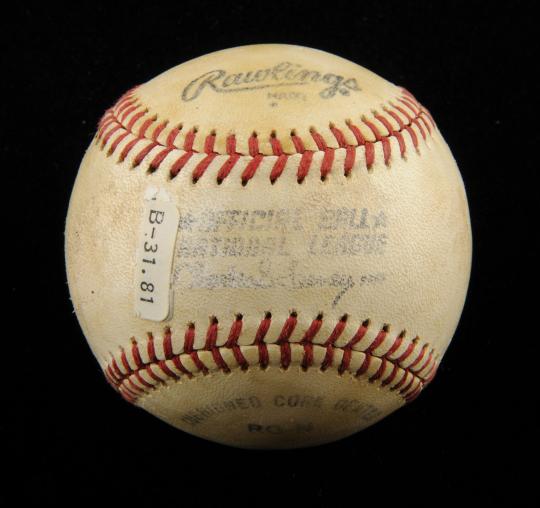

For decades, MLB baseballs featured a facsimile signature of the corresponding league president. This ball, used by the Phillies' Steve Carlton to record his 3,000th career strikeout on April 29, 1981, features the signature of longtime National League president Charles "Chub" Feeney. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

“But that’s not the last of it. It has definitely put the game back where it was 10 or 12 years ago, where a fast, quick-thinking club like the Cardinals has the advantage. The era is slugging is over as far as the National League is concerned. Only two of our teams, the Cardinals and the Giants, really adopted themselves to the new ball this year, but every manager in the league will be playing it for all it’s worth next season.”

Later that decade, the two major leagues again differed on their opinion on the construction of the official ball. In December 1937, the NL voted to deaden the ball while the AL retained its “rabbit.”

The new NL ball, with five strands in the seams instead of four, was expected to result in a year of improved pitching and tighter games, while in the AL, the Yankees led the chorus to keep the status qua and retain the livelier ball.

“The new ball will give the pitchers a better grip,” said NL President Ford Frick, “but it will not impair the possibility of long hits if the ball is hit right.”

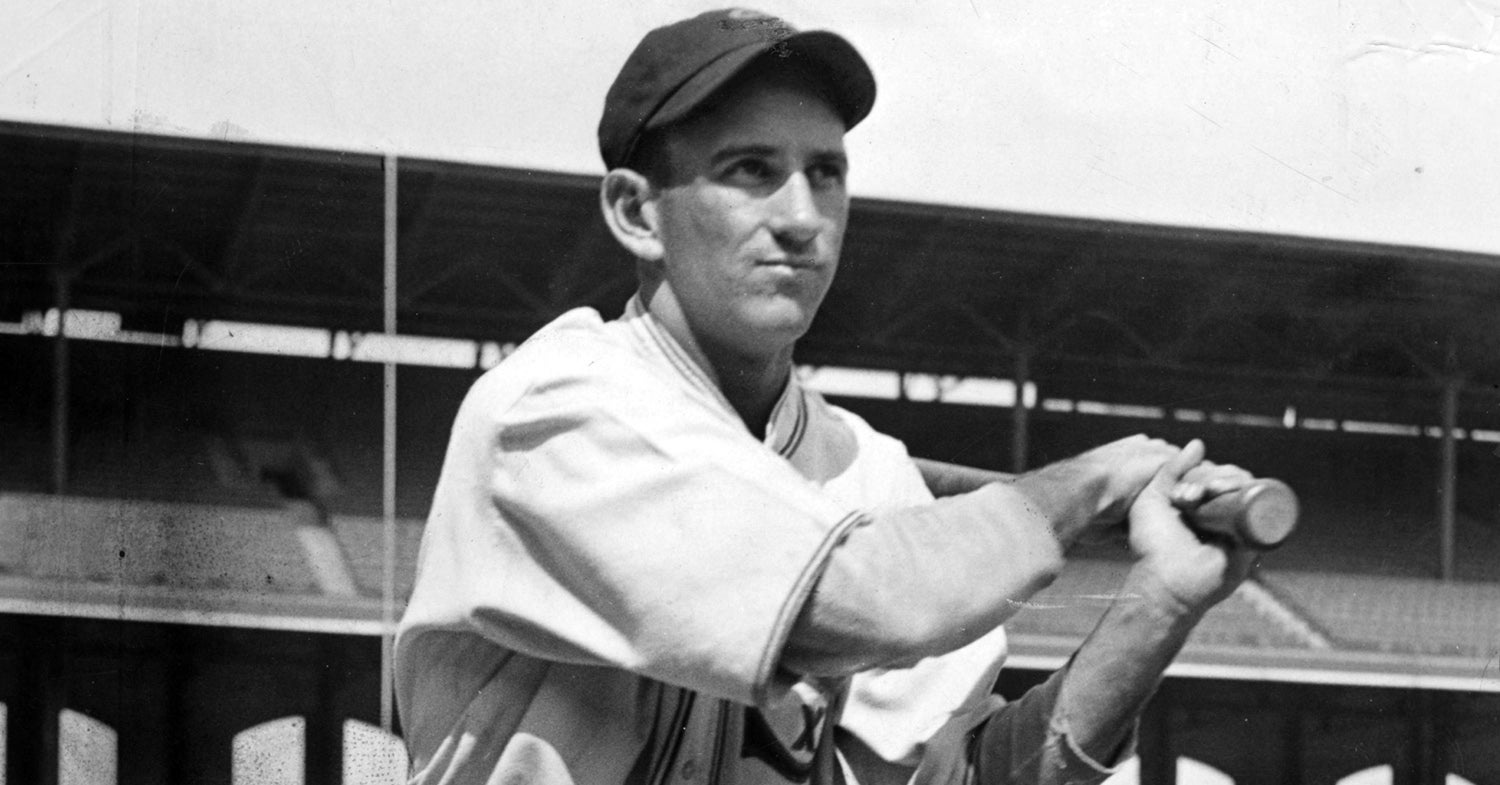

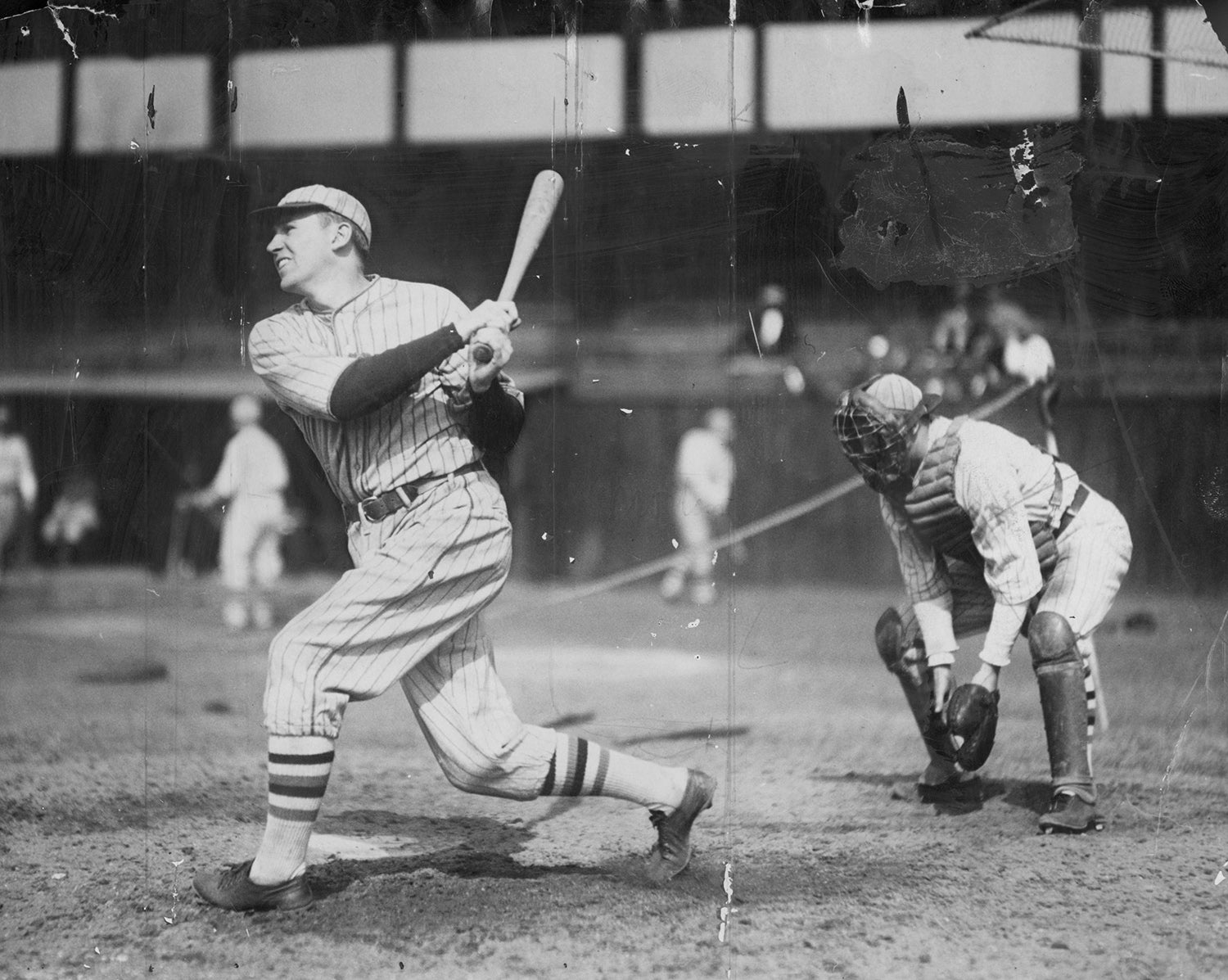

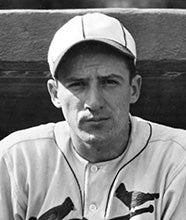

Future Hall of Famer Joe Medwick, in 1938 still a slugging leftfielder with the Cardinals, said before the start of the season: “I’m going to take my same cut at the ball and let my batting average rest on that. If I hit it, it might not go as far, but it will go just as straight.”

Another pair of future Hall of Famers – Jimmie Foxx and Chuck Klein – tested the NL’s new deadened balls at January 1938 trial at Oriole Park in Baltimore.

“I don’t think the dead ball will hurt the .340 hitters in the National League as much as the .275 players,” Foxx said. “I look for a difference of 20 points for the light men but only four or five for the sluggers.”

Added Chuck Klein: “If you like a ‘whooshy’ ball – that’s okay. I like the old ball – but it doesn’t make much difference.”

Ty Cobb, elected to the Hall of Fame in 1936 as part of the institution’s first class, praised the NL for adding one more stitch to the seam of the sphere.

“It means more close games. More close games mean more excitement for the crowd. It means better pitching and more base running,” Cobb said before the start of the season. “Anybody would rather watch one of those 2-1 or 3-2 games even if it is on a sandlot, than a 12-1 game, even if played in a World Series.”

Prior to the start of the 1938 season, future Hall of Famer Clark Griffith, the owner of the Washington Senators and the winner of 237 big league games at the turn of the century, wanted a government agency to test the new NL balls.

“I’ve worked out an arrangement with the Bureau of Standards to test the so-called National League dead ball and the so-called American League rabbit ball,” Griffith said. “This experiment will be a mechanical one. Machines will do all the slugging and nobody will do any pitching.”

In March 1938, the Bureau of Standards report said its tests on liveliness of “dead” and “live” baseballs showed “no difference of any practical significance.”

“Some National League balls are more lively than some American League balls and some are less lively,” said the bureau, summing up the situation.

In fact, while the AL loop remained relatively consistent from 1937 to 1938, batting .281 both seasons while its homer total rose from 806 to 864, any changes in the NL circuit were negligible, as the batting average went from .272 in 1937 and decreased to .267 the next year, while the homer totals went from 624 to 611.

After the 1938 season, the NL, whose new ball wasn’t as dead as the manufacturers promised, announced it intended to keep it in play. Also, AL President William Harridge said that its teams would conform to the specifications of the NL ball, but made clear it wasn’t aimed at toning down the home run power of a New York Yankees team coming off three straight World Series titles.

While there has been wild speculation over the recent decades about changes to the baseball – claims big league baseball has consistently denied – even back on 1939, a longtime executive with Spalding, who manufactured the balls at the time, vehemently refuted any speculation on unconfirmed alterations.

In a letter to New York Times sports columnist John Kieran, Spalding’s Julian W. Curtiss wrote:

“I note that one of your correspondents is still talking of the ‘lively baseball’ and a little comment of your own would indicate that you hold the same opinion. Now, sir, won’t you please believe me when I say that as far as I know the only thing in baseball that has not changed in many years is the baseball itself. In liveliness and construction there has been practically no change in 28 years.

“The American League officials asked me to attend their meeting recently and I gladly did. I made the statement then as I have made it here, and Connie Mack, who was on hand, backed me up and said, ‘Mr. Curtiss, you are quite right.’ I have been closely associated with the making of the ball since 1885 – in fact, I really have had charge of it – and I ought to know something about it.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum