- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

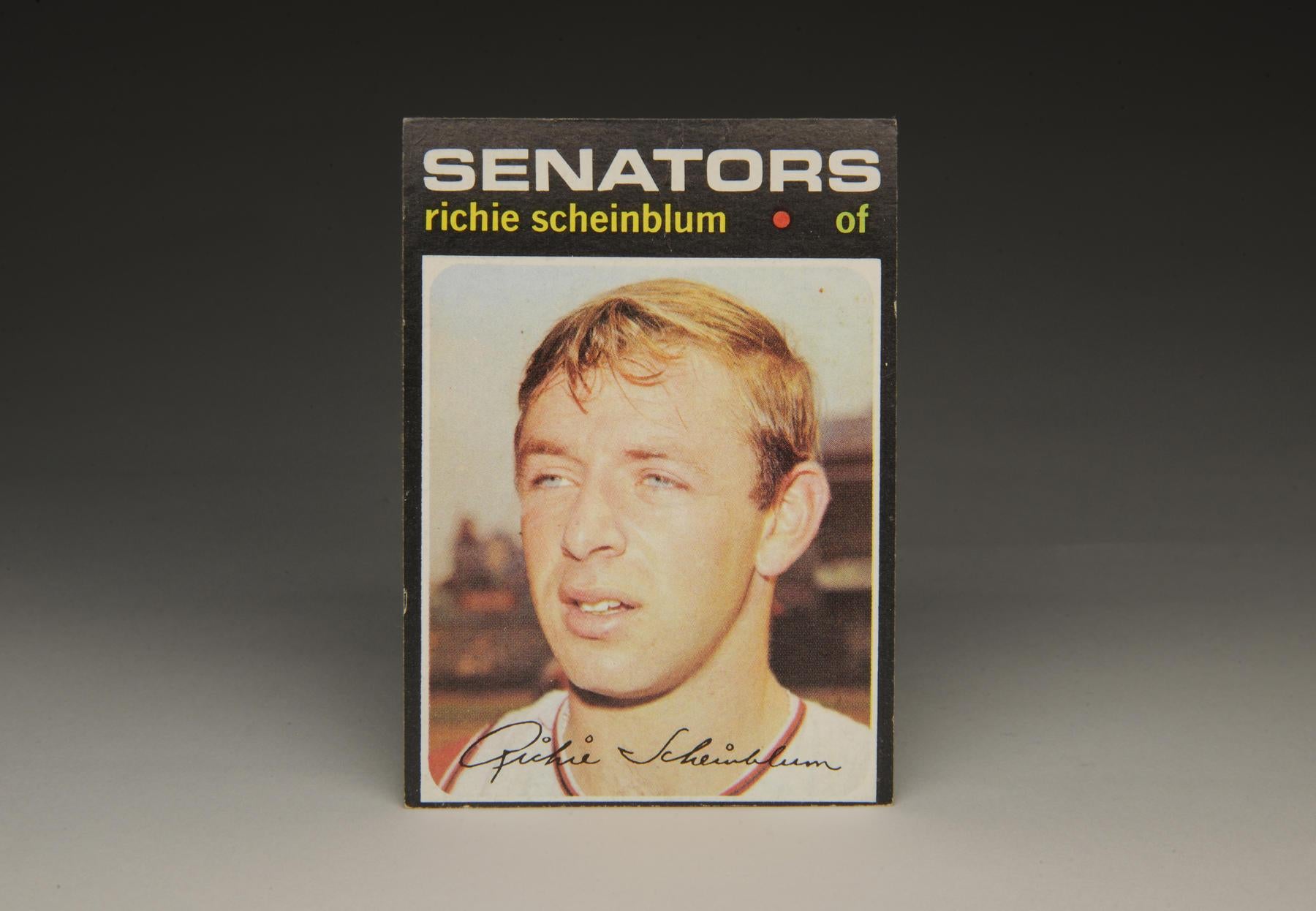

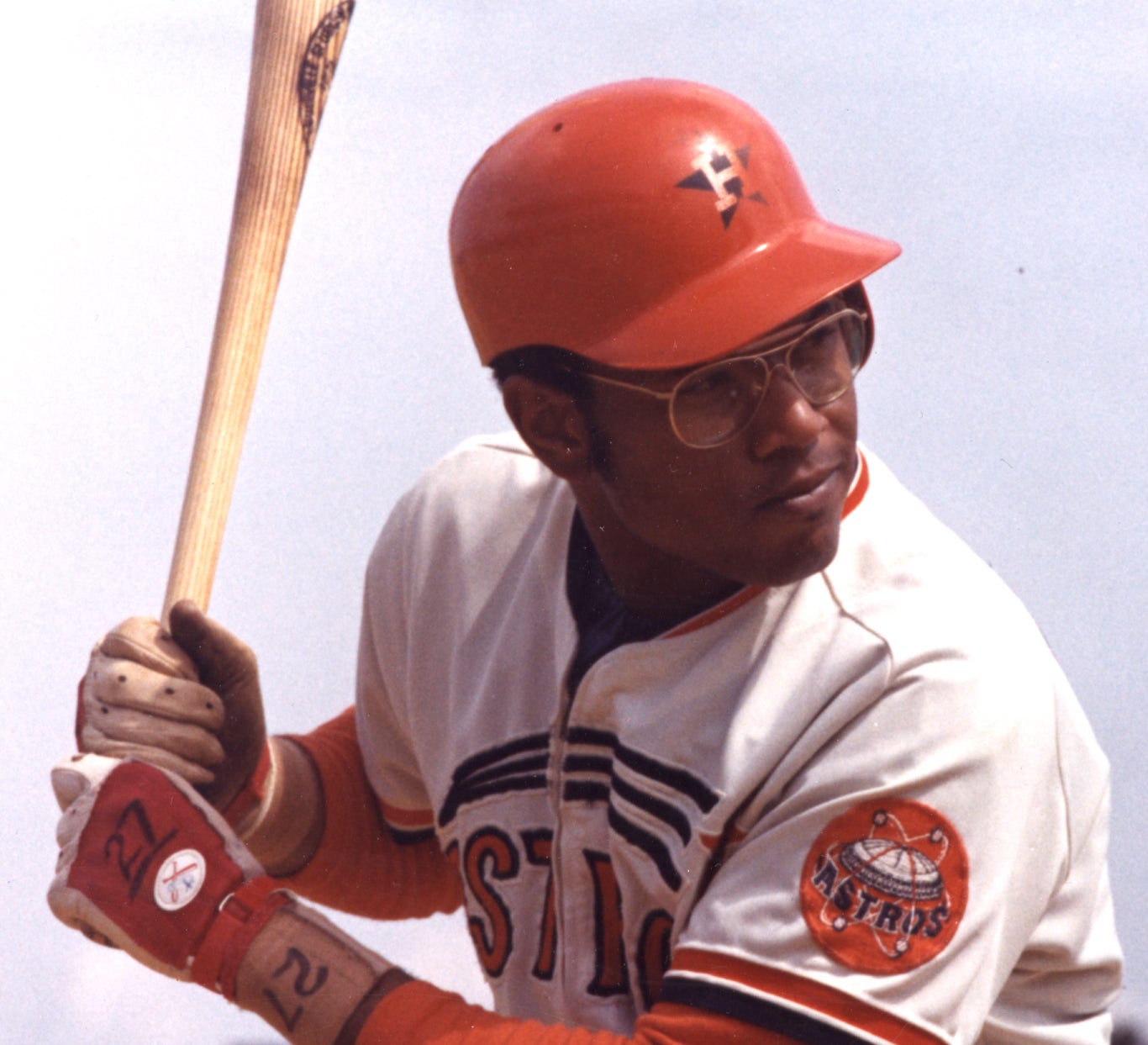

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

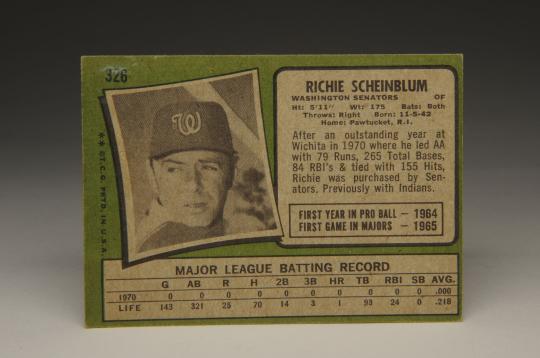

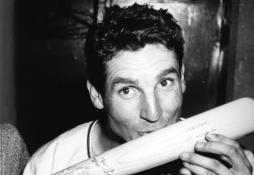

By his own admission, Richie Scheinblum appears as if he has just woken up at the very moment his baseball card photograph is being taken. “On two of my cards, I look like I just got out of bed and someone snapped [a picture],” Scheinblum said during a visit to Cooperstown back in 2004. Clearly, one of those cards is this one; it is part of Topps’ famed 1971 black-bordered set, which portrays him as a member of the Washington Senators, even though he is clearly wearing the jersey of the Cleveland Indians. Thanks to the capless pose seen here, Topps has created the illusion that Scheinblum is a full-fledged Senator.

With his hair out of place and his face a bit puffy, Scheinblum doesn’t look his best here, but he still has fond memories of tracking his Topps cards. It was a yearly ritual that actually helped him determine whether he was going to make his team’s Opening Day roster. “It was the most fun [to see myself on a card]. But at the time, very nerve-wracking. A very good friend of mine named Sy Berger, who was with Topps Bubble Gum, would walk into the locker room, and all the fringe players, including myself, would wait for Sy to come back. He’d wink at me, so I knew I’d made the team. Topps knew who actually was going to make the 25-man roster before anybody else did. So guys would go by and they’d tug on Sy’s shirt and say, ‘Sy, did I make it this year? Are you doing a card for me?’ It was a very unique situation.”

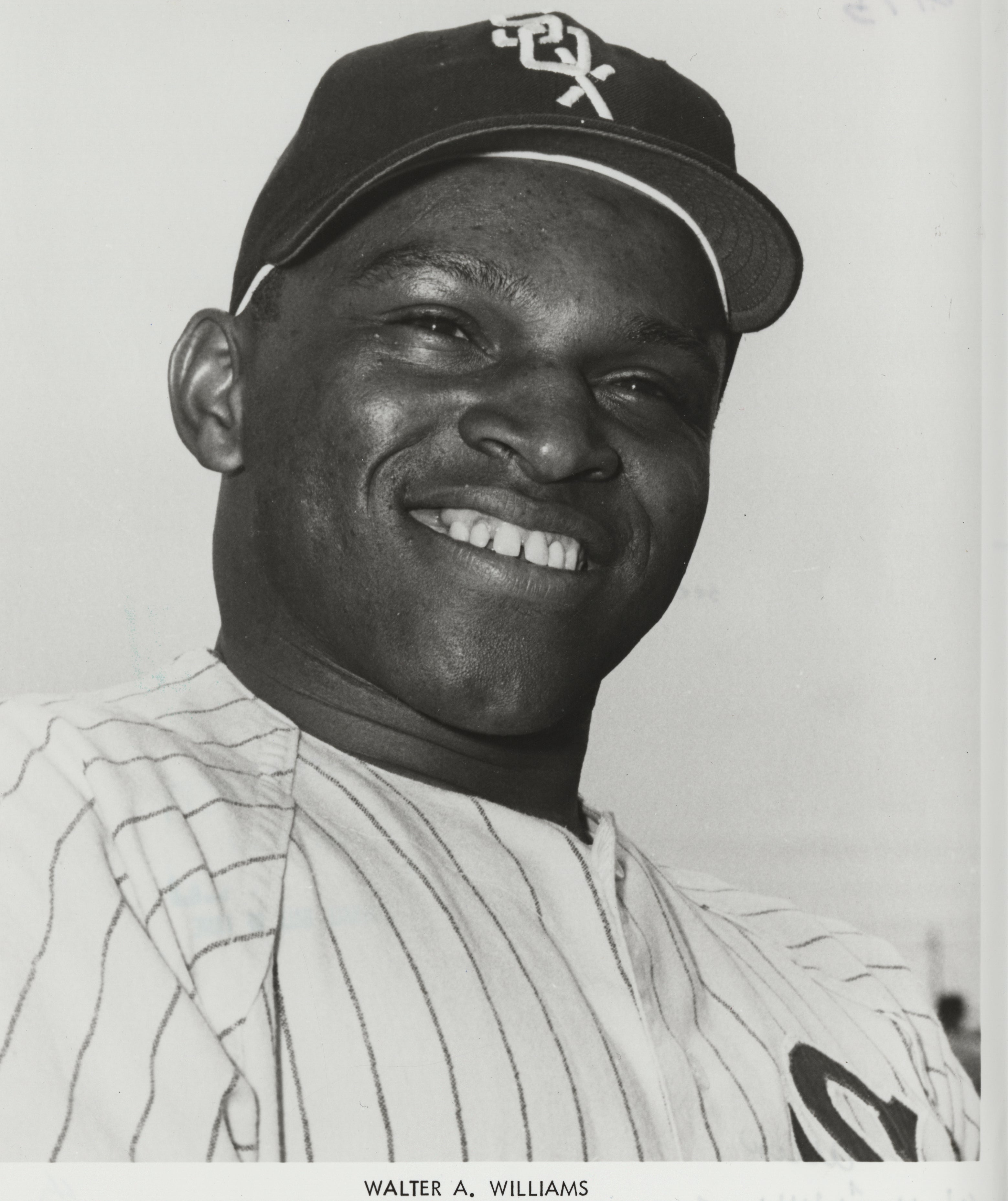

Known as a free spirit during his playing days, Scheinblum visited the Hall of Fame in August of 2004 as part of a Jewish Baseball Conference at the Museum. The event was attended by a number of Jewish players, including Ron Blomberg (the first designated hitter), Mike Epstein (who was famously nicknamed “Superjew”), and Elliott Maddox and Bob Tufts (both converts to Judaism). Like the other players, Scheinblum was more than happy to talk about his experiences as a Jewish major leaguer.

Off-the-field circumstances tended to overshadow Scheinblum’s playing ability. The media sometimes played up his Jewish heritage, while also noting that he was an intriguing mix of Polish, Russian and German heritage. On a lighter note, he also gained a bit of fame for filming a series of hair-transplant television commercials, making him a predecessor to the likes of Sy Sperling.

Scheinblum’s ascent to the major leagues was somewhat unlikely, given the obstacles of his youth. Born in the south Bronx, he idolized Rocky Colavito (another native New Yorker) while enduring a difficult childhood. His mother was hospitalized shortly after his birth; she died young, when he was only seven years old. His father decided to move the family to Englewood, N.J., where Richie struggled with his schoolwork. To make matters more challenging, Richie’s father tried to discourage him from playing baseball.

In some ways, Scheinblum was saved by his Little League coach, who happened to be a woman. She was a former amateur second baseman by the name of Janet Murk. Feeling that he could take advantage of right-handed pitchers, Murk encouraged Scheinblum to switch-hit. Thanks to the intervention of Murk, Scheinblum blossomed as an amateur, eventually becoming a terrific minor league hitter.

Yet a professional career did not come easily. A separated shoulder scared off some scouts. In order to prove his standing, he decided to play in a college summer league. He played games at night, but needed a paying job in the daytime, so he became an ice cube maker, of all things. “We worked from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m.,” Scheinblum told the Sporting News. “We were paid 80 cents an hour for making ice cubes for the Polar Bear Ice Cube Company.” As part of the job, he had to stand in a room where the temperature was 30 degrees below zero.

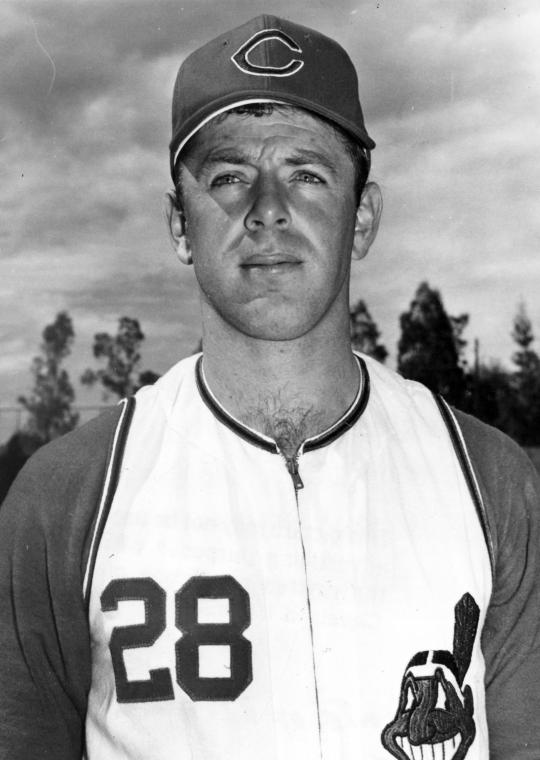

Even after signing with the Indians’ organization, Scheinblum failed to establish himself as an everyday major leaguer, in part because of his tendency to fret and worry about his play. A notoriously slow starter who hated to hit in cold weather (perhaps because it stirred memories of making those ice cubes), Scheinblum struggled to make a good first impression each spring. No better example could be found than in 1969, when the Indians gave him his first true dose of playing time, but he started the season in an abysmal 0-for-34 rut for the Indians. When the Indians acquired Hawk Harrelson in a trade, Scheinblum found himself on the bench. That entire season proved a long scuffle, as he finished with a .186 batting average and only one home run in nearly 200 at-bats.

As if those struggles weren’t difficult enough, Scheinblum also had to suffer the indignity of hearing public address announcers and broadcasters mangle the pronunciation of his last name. One announcer pronounced his name as “Shine-boom,” instead of the proper pronunciation of “Shine-bloom.” Another somehow called him “Shine-boop,” and still another referred to him rather bizarrely as “Shine-bottom.” If only they had consulted the American League Red Book, they would have found the correct pronunciation.

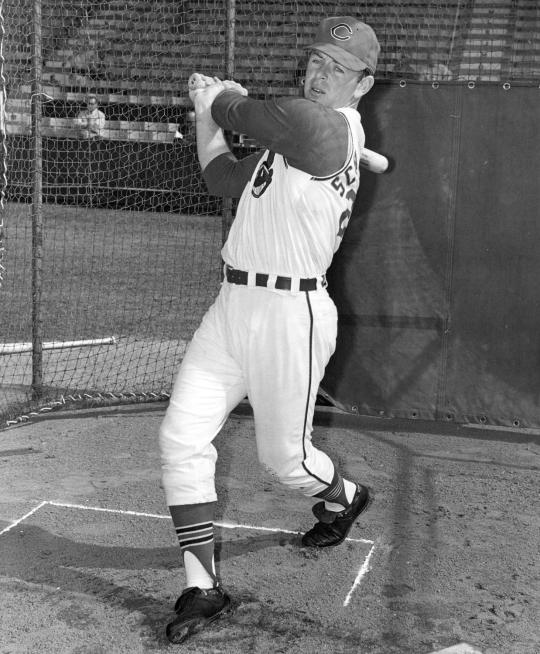

After his lost season of 1969, the Indians sent Scheinblum back to the minor leagues in 1970. He prospered at Triple-A Wichita, hitting .337 with 24 home runs. But rather than give him another look in 1971, the Indians deemed him a non-prospect and sold his contract to the Senators.

A slow start to his career in Washington resulted in another minor league demotion. This time, Scheinblum went to Triple-A Denver, where he raked opposing pitchers to the tune of a .417 batting average by early August. While speculation grew that he might hit .400 for the season. Scheinblum fell off only slightly, settling for a .388 batting average. Clearly, he had nothing left to prove in the minor leagues, but he would not make the move with the Senators’ franchise, which was relocating from Washington to Texas. The newly formed Rangers instead sold his contract to the Kansas City Royals for $40,000.

The sale to Kansas City, a recent expansion team, was just the change that Scheinblum needed. In 1972, Scheinblum’s minor league hitting numbers finally translated into big league stardom. As the starting right fielder for the Royals and manager Bob Lemon, Scheinblum found himself hitting .341 in mid-July, which placed him in the lead in the American League batting race.

By early September, Scheinblum had started to slump. But his September struggles seemed trivial in comparison to other world sporting events. At the Munich Olympic Games, 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken prisoner and then murdered. In their memory, Scheinblum wore a black arm band on his Royals jersey. “I wore the emblematic black band,” Scheinblum told a reporter, “not only because they were Jewish athletes, but because they were human beings.”

On a far less important level, Scheinblum endured some physical problems the final month of the season. He was hit in each foot by a pitched ball—one by John “Blue Moon” Odom and another by future Hall of Famer Jim “Catfish” Hunter. Richie continued to play in pain, lost 18 points off his batting average, and settled for an even .300 batting average, but no batting title.

Perhaps concerned by his late-season swoon, the Royals considered the possibility of a trade. After the season, the Royals dealt him to the Cincinnati Reds for future star Hal McRae. The change in leagues did not help Scheinblum, who had to learn a new set of pitchers while settling for a role as a fourth outfielder behind established starters like Pete Rose, Bobby Tolan, and Cesar Geronimo. Given irregular playing time, Scheinblum batted only .222 in 29 games. At the June 15 trading deadline, the Reds dealt him back to the American League, this time to the California Angels for a pair of obscure players to be named later.

With the Angels, Scheinblum teamed with the aforementioned Mike Epstein to form what the Southern California media dubbed the “Bagel Battalion.” (It’s not quite as memorable as “Murderers’ Row,” but it’s more creative.) At first, Scheinblum played well for the Angels, batting .328 over the balance of the 1973 season. But a poor start to the 1974 season resulted in a return trade to the Royals; from there, the Royals sold him to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he was buried behind another band of talented outfielders, including future Hall of Famer Lou Brock.

Scheinblum was still only 31 years old and wanted to continue playing. He found a viable option in the Japanese Pacific League, signing a two-year contract with the Hiroshima Toyo Carp. As one of the first Jewish players to play in Japan, he found it difficult to explain his reasons behind not wanting to play during Yom Kippur.

In spite of the cultural struggle, Scheinblum hit well in his two seasons for the Carp. He would have played longer there, but he severed his Achilles tendon during the off season; the injury ended his career at the age of 33.

All in all, it was a winding road for Scheinblum, but it was also a road that saw him persevere time and time again. He essentially grew up without a mother. He had people tell him that a Jewish player like him wouldn’t make the major leagues. At times he struggled to hit, so much so that his career appeared to be in jeopardy. But ultimately, Richie Scheinblum made it. He also found his way onto several Topps cards.

Even if he didn’t exactly look like a model on one or two of them, Scheinblum always took solace in knowing that Topps thought him good enough to be worthy of eight different cards along the way. Any American boy would take pride in that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame