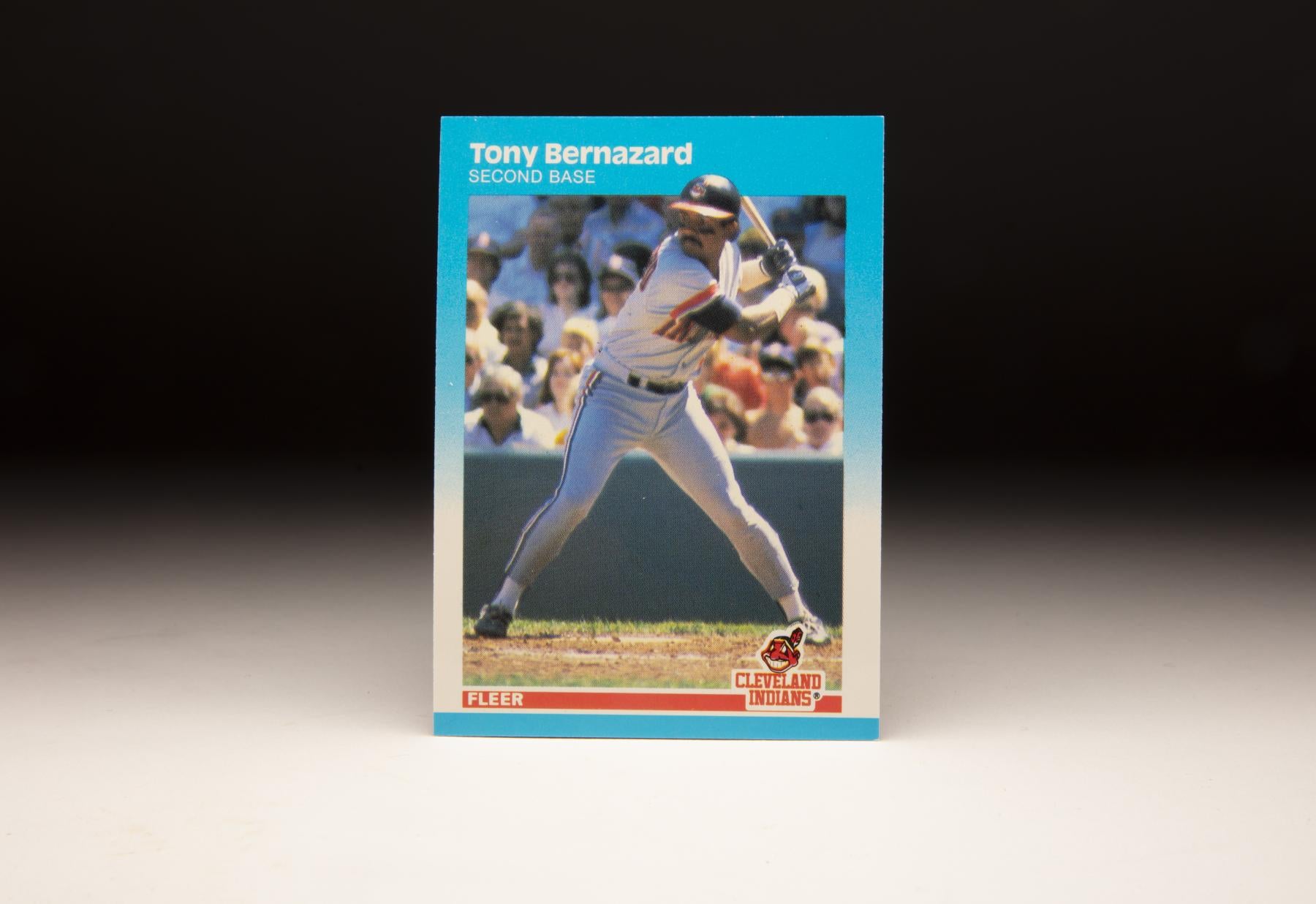

#CardCorner: 1987 Fleer Tony Bernazard

Tony Bernazard played 10 years in the big leagues and was maybe best known for a 1984 0-for-44 stretch at the plate that brought him to within one at-bat of history.

But Bernazard was also a solid second baseman who showed unusual power during three years in the Japan Pacific League and later served as a front office executive – a stint that admittedly did not end well – with the Mets.

In short, Bernazard’s fingerprints were all over the game for more than 40 years.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

Antonio Bernazard Garcia was born Aug. 24, 1956, in Caguas, Puerto Rico. Raised in a middle class family, Bernazard grew up surrounded by baseball – his younger brother, Oscar, played in the Pirates’ organization before a broken arm ended his career – and, like many of his countrymen, followed the exploits of national heroes like Sandy Alomar Sr. while learning the game from former big leaguer Vic Power.

“Baseball, you know, is our national game,” Bernazard told the Miami Herald in 1975 when he was a minor leaguer in the Expos system. “We play year-round, and sometimes I would be playing in two or three leagues at one time. You really don’t think about all the money you can make; every kid just wants to play in the big leagues.”

Though he stood just 5-foor-9, Bernazard possessed a strong upper body that allowed him to drive balls from both sides of the plate. Expos executive Mel Didier needed only a brief look at Bernazard before signing him on Nov. 13, 1973, giving him a bonus that was less than half of the $15,000 Oscar Bernazard got when he signed with the Pirates.

“There were 10 of the best players in Puerto Rico there, and they signed two of us,” said Bernazard, who came of age in the days before Puerto Rican players were eligible for the MLB Draft. “I was little, but I was strong. I work with weights a little, but mostly I was born with it.”

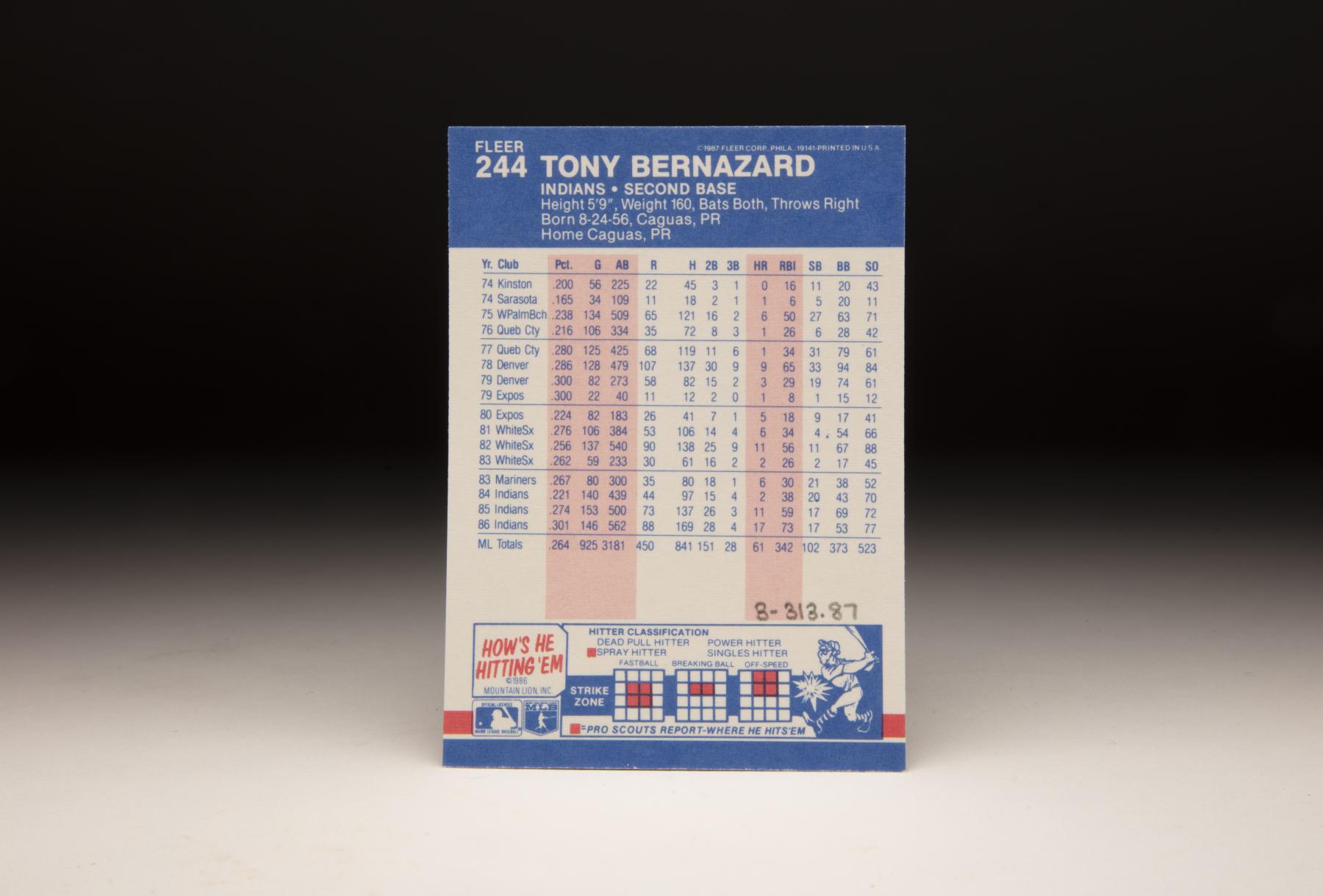

Bernazard struggled as a 17-year-old in 1974, hitting a combined .189 in two low-level leagues. But in 1975, he played a full season with Class A West Palm Beach of the Florida State league, batting .238 with 65 runs scored and 27 stolen bases.

Promoted to Quebec of the Double-A Eastern League in 1976, Bernazard hit .216 against players who were on the average four years older than him. He returned to Quebec in 1977, hitting .280 with 31 steals and earning a promotion to Triple-A Denver in 1978.

Playing in the high altitude of Denver, Bernazard hit .286 with team highs in runs (107), walks (94) and steals (33). He came to Expos camp in the spring of 1979 with virtually no chance of making the team due to the presence of veterans Dave Cash and Rodney Scott at second base, but Bernazard impressed everyone by hitting .320 with five steals en route to the team’s camp rookie of the year award.

Bernazard was optioned back to Denver on April 4. He was recalled on July 13 when shortstop Chris Speier went on the disabled list with a back injury and debuted that day, recording a double and drawing three walks in a doubleheader against the Padres. He was hitting .300 in August when he was sent back to Denver due to a catching shortage on the Expos, returning in September after hitting .300 with 19 steals in 82 games in Triple-A.

He finished the season batting .300 for the Expos over 22 contests – with an on-base percentage of .500 – as Montreal fell just short of the National League East title.

Cash was traded to San Diego following the 1979 season, but Scott maintained a grip on the second base job to start the 1980 campaign. But an early-season slump by Scott prompted Montreal manager Dick Williams to turn to Bernazard in April. After a solid start, however, Bernazard hit just .224 over 82 games as Williams tinkered with the lineup in a heated pennant race with the Phillies.

“I know that I can hit and that I can play in the majors,” Bernazard told the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press. “I don’t think about the minors. I know what happened (in 1979), but I have nothing left to prove there.

“I think I’ve earned my place up here. They are going to have to take it away from me because I’m not giving it up.”

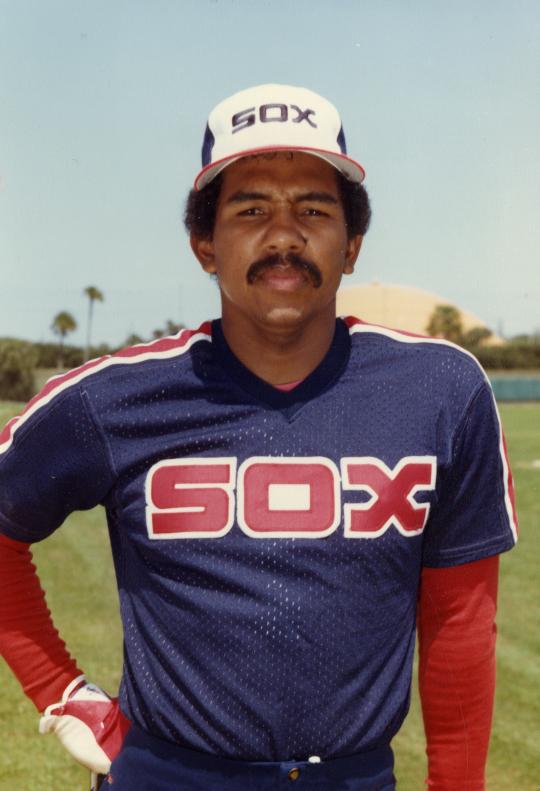

On Dec. 12, 1980, Bernazard was traded to the White Sox in a one-for-one deal for pitcher Rich Wortham.

“His minor league record was outstanding and he’s a good athlete,” White Sox manager Tony La Russa told the Chicago Tribune. “I think it would be to our advantage if things work out with Jimmy (Morrison) at third and Bernazard at second. If our new guy can’t hack it at second, we can always have Greg Pryor for the job.”

Bernazard proved more than capable of playing regularly in 1981, appearing in each of the White Sox’s 106 games while batting .276 with a 3.7 Wins Above Replacement figure that was third-best on the team.

“Last year, I’d have an at-bat here and an at-bat there,” Bernazard told the Associated Press. “It’s not like playing every day where you do what the situation calls for.”

It was a move that ended Bernazard’s playing career. But he quickly found a second baseball life with the Major League Baseball Players Association, serving as a union liaison for Latin American players. After a dozen years in that role, Bernazard joined the Mets’ front office in November of 2004 as a special assistant to general manager Omar Minaya.

“He has experience as a player,” Minaya told the Central New Jersey Home News, “and his time in the union gives him a unique pulse on what today’s players are thinking and what they are about on and off the field.”

Bernazard helped assemble the Mets team that advanced to the NLCS in 2006. But less than two years later, Bernazard was widely reported to have been a prime mover in the decision that cost Willie Randolph the team’s managerial job.

Then in the summer of 2009, Bernazard landed in the New York tabloid press regularly during a week where he was accused to berating a team official about a seating assignment at a Mets game and then later allegedly challenged Mets minor leaguers – seemingly to provoke a fight – at Double-A Binghamton. Bernazard was soon dismissed.

On the field, Bernazard finished his 10-year big league career with a .262 batting average, 970 hits and 113 stolen bases. Listed at 5-foot-9 and 150 pounds for much of his career, Bernazard willed himself into a role as a solid second baseman for most of a decade.

“Talk about getting the most out of your ability,” La Russa said of Bernazard during his time in Chicago. “He gets every ounce. The only time he gets mad at me is when I take him out of the lineup.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum