- Home

- Our Stories

- Cooperstown clutch: Hall of Famers’ walk-offs have powered championship runs

Cooperstown clutch: Hall of Famers’ walk-offs have powered championship runs

Earning a bronze plaque in Cooperstown is, above all, a numbers game. Each year, the Hall of Fame electee(s) add to a precedent of wins, home runs, strikeouts, hits, Wins Above Replacement, etc. by which future candidates will be judged.

But belonging in the Hall of Fame isn’t just a matter of statistics. Not all base hits are created equal, and the ability to come through with a postseason game on the line has separated many baseball greats from their peers.

These legendary hitters, forever enshrined in Cooperstown, are just some of the Hall of Famers who have delivered walk-off hits en route to World Series championships.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

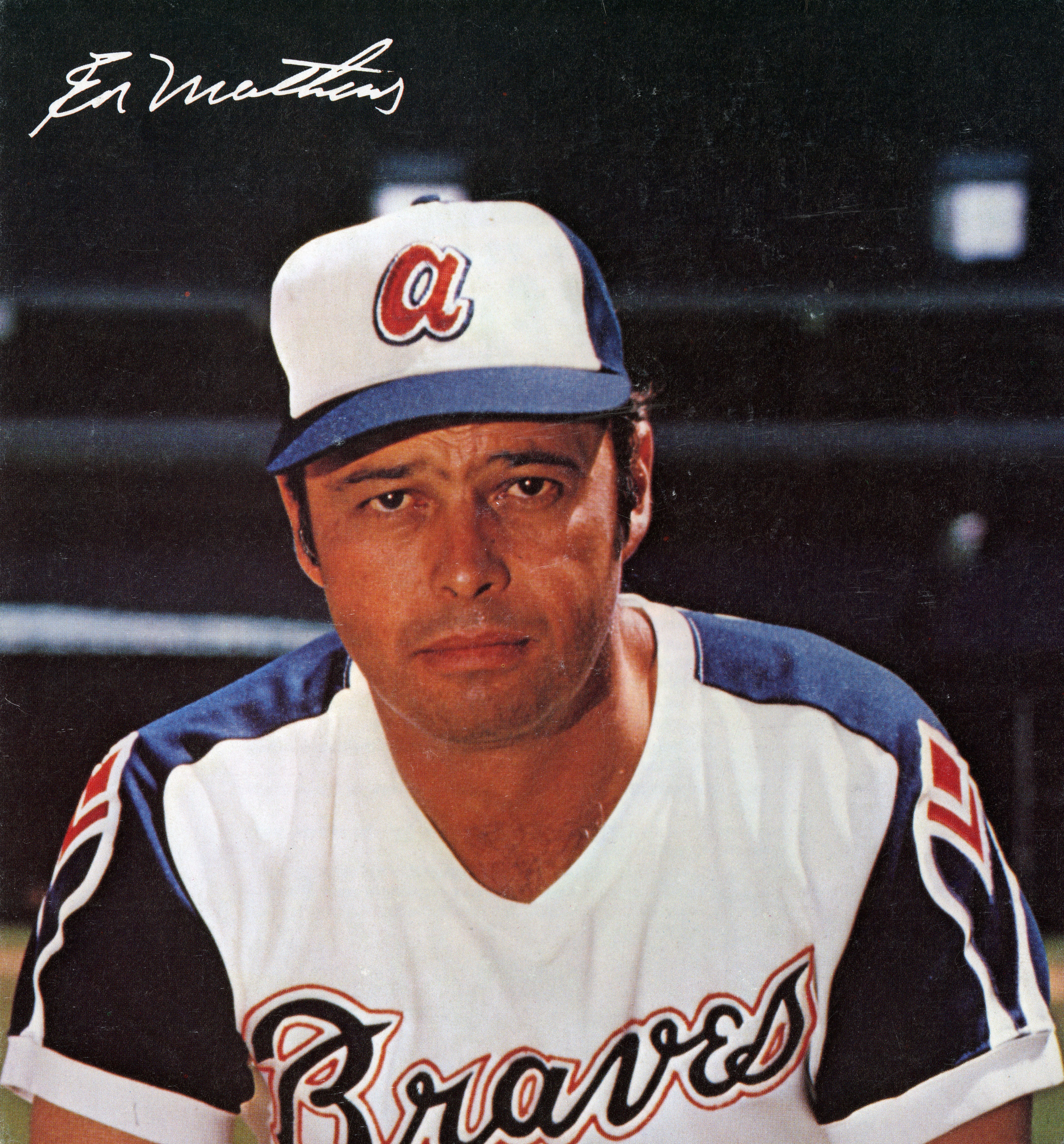

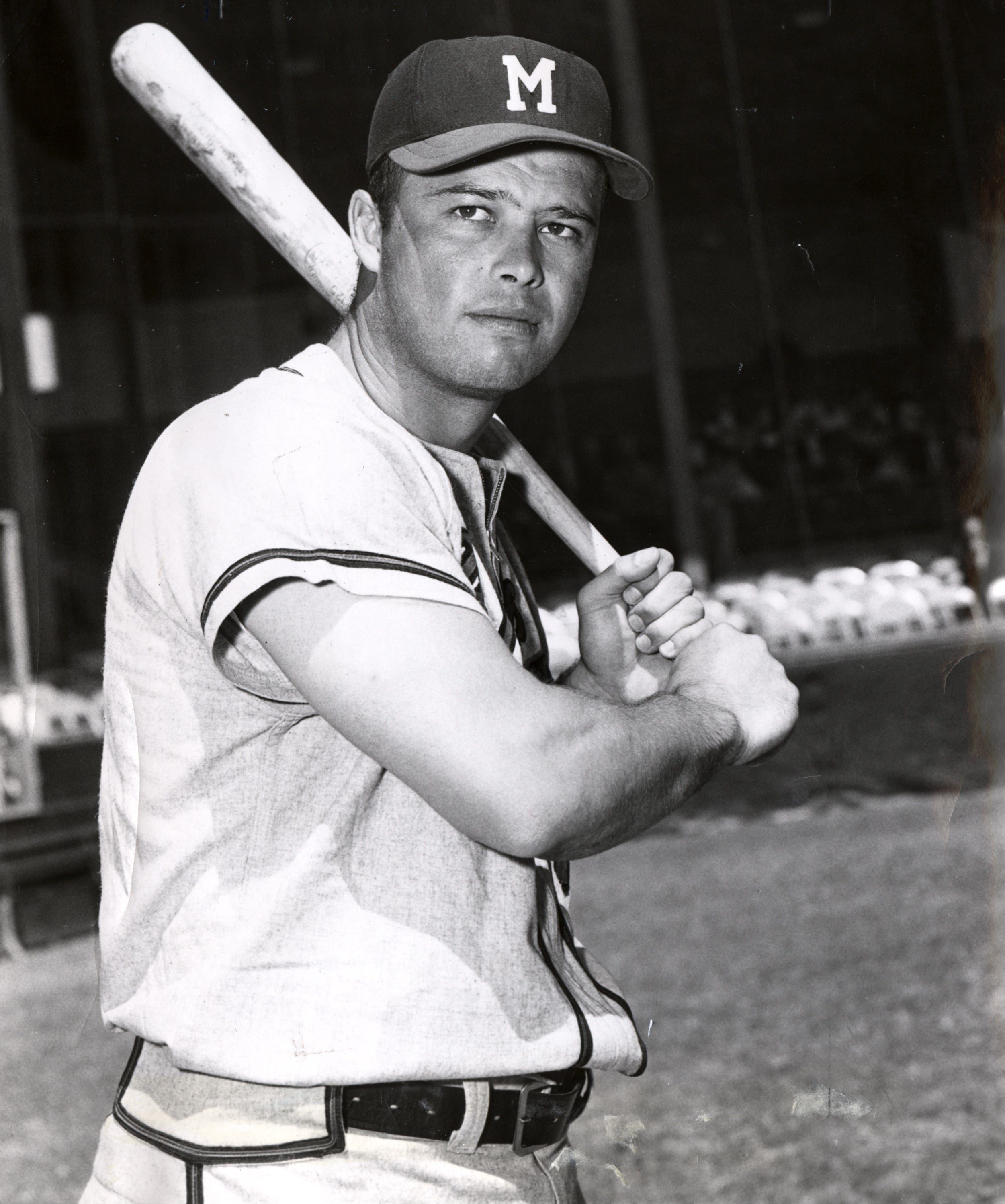

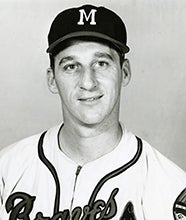

Eddie Mathews, the 25-year-old with six seasons and 222 home runs under his belt, was having a forgettable World Series debut in 1957. He had drawn five walks through three games but never came around to score and didn’t tally a hit. Game 3, a 12-3 defeat at the hands of the Yankees, left Mathews’ Braves trailing the series 2-1.

Prospects were brighter for Game 4, however, considering Warren Spahn was pitching for Milwaukee. Spahn, who would win the 1957 National League Cy Young Award, took the mound on Oct. 6 and held New York to one run through eight frames. The Braves led 4-1 thanks to fourth-inning blasts by Hank Aaron and Frank Torre.

But things unraveled in the ninth inning with Spahn one out from an imperative, complete game victory. Yogi Berra and Gil McDougald singled before Elston Howard tied it with a home run, stunning the future Hall of Fame left-hander and Braves fans.

“Gloom in waves settled over the crowd of 45,804 in Milwaukee County Stadium,” wrote the Wisconsin State Journal. “It grew heavier, if that were possible, in the top of the 10th when New York went ahead, 5-4, on a single by Tony Kubek and a triple by Hank Bauer.”

But Milwaukee’s Johnny Logan responded with an RBI double. Mathews, who had broken his slump and scored after a fourth-inning double, then smacked a walk-off home run over the right-field fence.

Reliever Bob Grim, baseball’s regular season saves leader, was on his way to New York’s dugout before Mathews’ blast even landed.

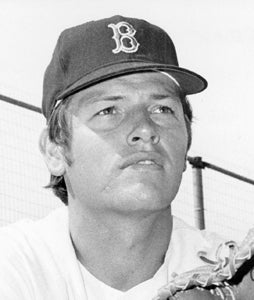

At age 21, Eddie Mathews hit .302 and led baseball with 47 home runs. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“The crowd went completely and understandably wild,” the State Journal wrote. “The fans had seen victory snatched away, had stared probable defeat in the face, now saw that probable defeat become certain victory.

“This was a great game, a far cry from the rather miserable exhibition of 24 hours earlier,” the State Journal continued. “The Braves didn’t lose heart when a malignant fate turned on them, they refused to play dead for the Yankees.”

After nearly falling into a 3-games-to-1 hole, the Braves were certainly alive. Mathews scored the only run off Whitey Ford in Game 5, a 1-0 victory. He also started the scoring in Game 7 with a two-run double, leading Milwaukee to the second championship in franchise history.

Another epic Fall Classic took place 18 years later between the Reds and Red Sox, both of whom enjoyed walk-off wins in the series. Boston’s may have been more picturesque, with Carlton Fisk waving his home run inside the left-field foul pole to force Game 7, but Cincinnati’s in Game 3 was of equal importance.

The World Series was tied at a game apiece. Back home at Riverfront Stadium on Oct. 14, 1975, Cincinnati built a lead with homers by Johnny Bench, Dave Concepción and César Gerónimo. Joe Morgan added a sacrifice fly to make it 5-1.

Gary Nolan, the Reds’ regular season innings leader, exited after four innings with a stiff neck. Boston battled back, tagging each of the four relievers who followed with an earned run.

Dwight Evans’ game-tying, two-run bomb in the ninth sent Game 3 to extras, where controversy ensued after Gerónimo’s leadoff single. Ed Armbrister bounced a bunt in front of the plate and, exiting the right-handed batter’s box, crossed paths with the catcher, Fisk.

While attempting to dodge Armbrister, Fisk fired the ball into center field to put runners on second and third. He and his Boston teammates were adamant it was interference, but no call was made. An intentional walk of Pete Rose loaded the bases with one out for Morgan.

Like Mathews, Morgan was an accomplished hitter who hadn’t yet played his best in October: Entering the 1975 World Series, the second baseman had hit .176 in 20 career postseason games. With Boston’s outfielders playing shallow to defend against a sacrifice fly, Morgan swatted one over center fielder Fred Lynn’s head to walk it off.

“That evens the series 1-1-1,” an irate Red Sox player said in the clubhouse postgame. “One for us, one for the Reds and one for the umpires.”

No matter, the Big Red Machine had seized a 2-games-to-1 lead in a series they would eventually win in seven. Morgan would strike again in Game 7 with a ninth-inning go-ahead single, capturing the first of two titles for those dominant 1970s Reds.

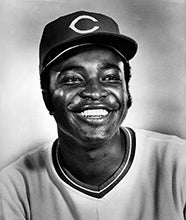

Joe Morgan, one of three future Hall of Fame players on the 1975 Reds, tallied two game-winning hits in the World Series that year. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Whereas the 1975 Reds were a powerhouse and a World Series favorite, having scored the most runs in baseball and allowed the fourth fewest, the 2003 Florida Marlins were a less likely postseason contender. That club finished the regular campaign at or below league average in most major offensive categories — runs per game, home runs, on-base percentage, OPS, etc. — while faring slightly better with pitching and defense. A 91-71 record earned Miami the National League Wild Card spot, marking the second postseason appearance in the franchise’s young history. The first, in 1997, ended with a World Series title.

On Jan. 28, 2003, Iván Rodríguez, having collected 10 All-Star selections, 10 Gold Glove Awards and an American League MVP Award before turning 30, joined the Marlins on a one-year, $10 million deal. Pudge enjoyed a typically productive, albeit award-free season with the Fish, hitting .297 with 16 home runs, 36 doubles and 85 RBI. Rodríguez had reached the postseason three times in the 1990s but never advanced, with his Rangers going 1-9 in ALDS play versus the Yankees.

The Marlins split the NLDS’ first two games with the 100-win Giants and returned to Pro Player Stadium for a thrilling Game 3 on Oct. 3. Rodríguez, batting third for Florida, homered in the first for a 2-0 lead.

San Francisco didn’t get to Marlins starter Mark Redman until the sixth, when a two-run rally tied the game. And in the top of the 11th, an unearned run gave the Giants a 3-2 advantage.

But Florida positioned itself to respond in the bottom of the inning. With a couple baserunners aboard, up came Miguel Cabrera, who had been omitted from the starting lineup after striking out four times in San Francisco. The promising 20-year-old rookie bunted the runners to second and third. After an intentional walk to Juan Pierre, Luis Castillo failed to deliver, so Rodríguez stepped up for a moment as pressure-packed as they come: Two outs, bases loaded and a one-run deficit, with a chance to end it.

That he did, lining an outer-half fastball to right field for a walk-off victory. Pudge went 2-for-5 with a walk and four RBI, a clutch performance in the early stages of a legendary October.

“Best game I’ve ever been associated with, by far,” Pierre told the Miami Herald. “I was just happy for Pudge. He battled a two-strike count. He put us on his back tonight… the look on Pudge’s face after he got the hit was worth anything.”

In fact, Pudge put the Marlins on his back all postseason as they defeated the Giants in four, the Cubs in seven and the Yankees in six for another championship for the Marlins. The 17-game run saw Rodríguez, the NLCS MVP, hit .313 with three home runs and 17 RBI.

Pudge was one-and-done with Florida, moving on to the Tigers that offseason, but his fingerprints were all over the Marlins’ 2003 title.

Justin Alpert was a digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum