- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Ed Charles

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Ed Charles

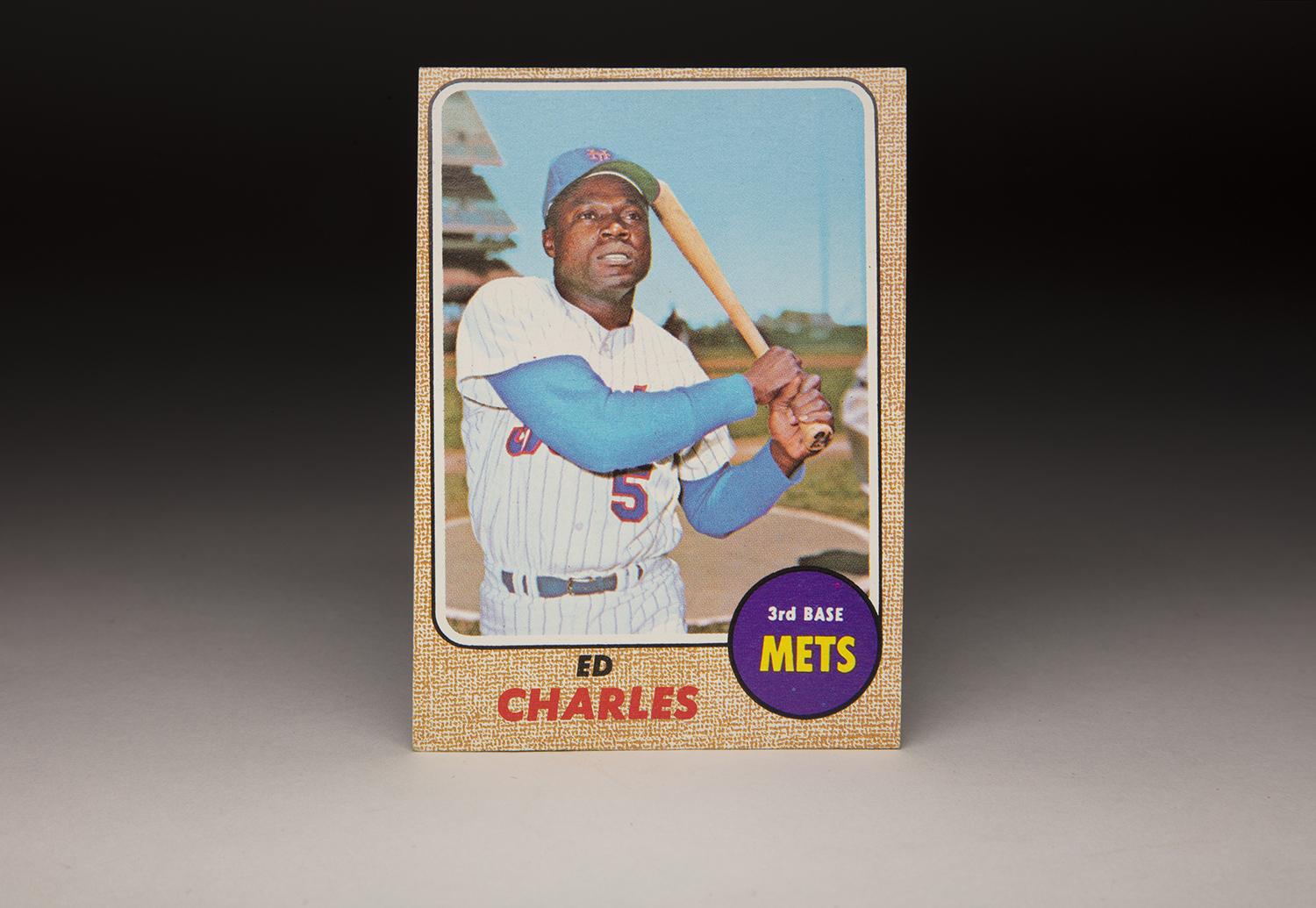

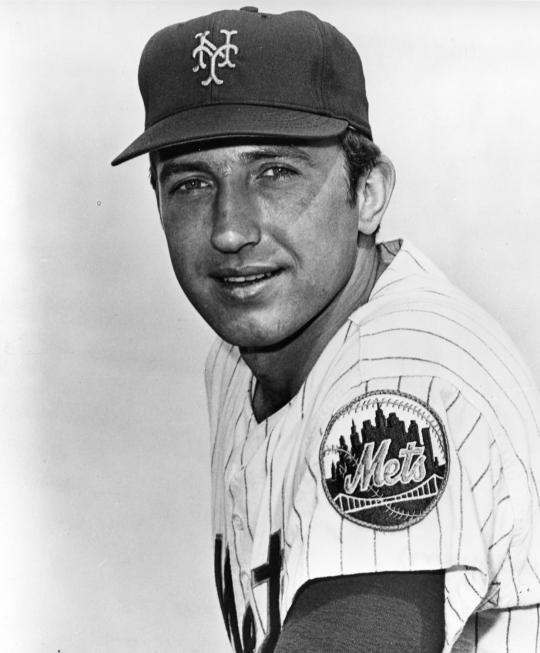

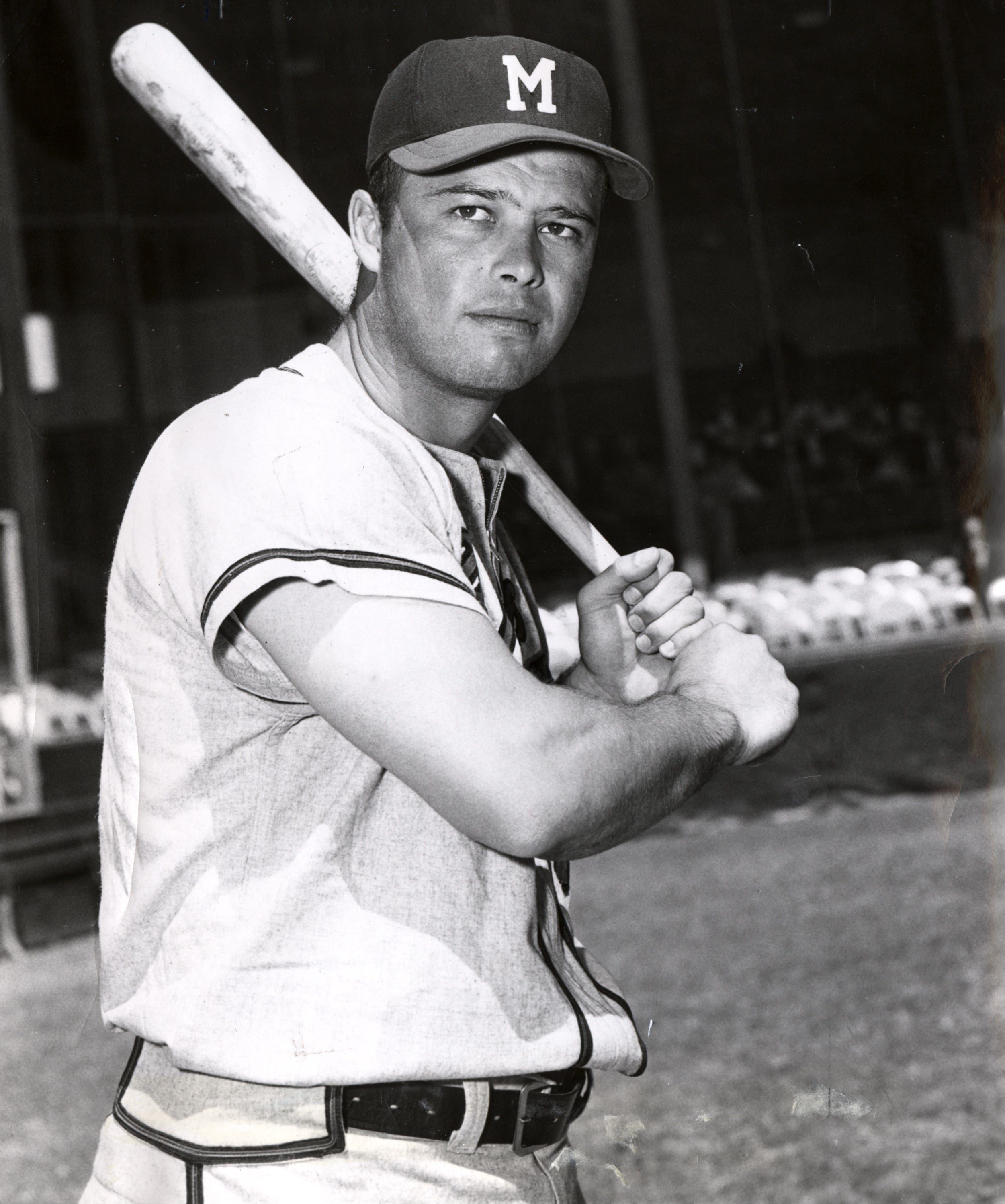

For fans who collected baseball cards in the 1960s, I suppose this is how they remember cards: Photographs taken on sun-splashed days at venues like Shea Stadium, with players clearly posing against blue sky backgrounds. Oftentimes, those poses took place with bat in hand. All of this is evident on Ed Charles’ 1968 Topps card.

Not only does Charles present us with a finish to his pretend swing, but he completes the picture by looking skyward, as if he is tracking the imaginary ball that he just hit. (In this case, he would have hit the ball into the grandstand at Shea Stadium, since his back is to the Shea outfield.)

For today’s younger collectors, these poses come across as hokey and corny, and I suppose that they are. But there was something innocent and childlike in these photographs. At a time when action photographs were not featured on baseball cards, this pose, a feigned swing of the bat, was as close as we could get to game action. Let’s give Charles some credit for doing his best to perpetuate the myth, in pretending that he hit an actual ball and tracked its flight. Charles deserves an A+ for effort.

Charles, who died earlier in March at the age of 86, usually did make the effort. He remains a symbol of perseverance on so many fronts. He was a player who overcame racial bigotry – again and again – in achieving success on the ballfield. He was also a player who overcome the odds, struggling in the minor leagues for so many years but never giving up. How many players toil for 10 years in the minors before earning their first call-up to the big leagues? Ed Charles was one of the few who persisted for so long, and still made it.

In 1952, Charles considered an offer from the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues, but instead signed his first professional contract with the Boston Braves’ organization, even though he had not finished high school. (About a decade later, he took the high school equivalency exam, passed it, and earned his diploma.) Charles would never play for the parent team, instead spending nearly a decade in the Braves’ farm system. He debuted in ’52 as a shortstop for a Canadian franchise in the old Provincial League in 1952. Playing for Quebec, he found that many white fans were in his corner, more than willing to accept a young African-American ballplayer.

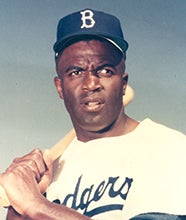

In 1953, Charles played at Fort Lauderdale, where he was generally treated well, but the situation changed when he moved on to Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1955 and Jacksonville, Fla., in 1956. Life in the south was difficult at the time, exposing Charles to the Jim Crow laws that segregated Black citizens from white ones. Charles experienced first-hand some of the racism that had affected his hero, Jackie Robinson, in the military, not to mention the Negro Leagues, the minor leagues, and during his early years with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

A road trip to Knoxville, Tenn., provided Charles with an unwanted look at 1950s racism, but also a glimmer of hope for the future. During the game, an older white man taunted Charles relentlessly, calling him one foul name after another. Charles did his best to ignore the heckler, but he could not tune out the insults and the catcalling. In spite of that, Charlies played a good game that day, excelling at the plate and at shortstop.

After the game, Charles walked out of the ballpark; to his surprise, he saw the man waiting for him. The man did not want to berate Charles further; he wanted to congratulate him. The man extended his hand to Charles, who accepted the gesture. Years later, Charles recalled the exchange with the man in an interview with Wayne Coffey of the New York Daily News.

“He said to me, ‘By golly, n-----, you are one hell of a ballplayer.’ I just shook my head and walked on by him.”

The exchange left Charles frustrated, because of the man’s continuing ignorance, but at least Charles received an acknowledgment of his talent. It was a tiny step in the right direction.

Charles also dealt with the issue of racial segregation. In the South, his teams stayed at segregated hotels, forcing him and his Black teammates to find housing with local Black families. When his teams traveled by bus, they sometimes came upon diners and restaurants that would serve only white patrons. As a result, Charles had to suffer the indignity of eating on the bus, sometimes by himself if he had no Black teammates.

Those experiences motivated Charles to write about them, which he did eloquently in the form of poetry. On occasion, Charles was asked to recite some of his poetry on local television. Charles’ poetry was good, so good that he became known as “The Poet.”

In addition to racism, Charles faced the realities of wartime. With the United States involved in the Korean War, Charles spent a year and a half in the military, costing him valuable developmental time in the minor leagues. But duties to the nation came first, ahead of duties to himself and his career.

After returning from the war and showing mild promise as a hitter, Charles finally moved up to Triple-A late in 1956. Playing for Wichita, he hit just .175 in 15 games. He wasn’t one to impress scouts with his physique either. Charles stood only 5-foot-9, and carried 180 pounds on his stocky frame. Scouts preferred prospects who were long and lean, and not built like fireplugs, as Charles was.

So in 1957, the Braves (by now relocated to Milwaukee) demoted him two full levels, all the way down to the Class A SALLY League. Now back in Jacksonville, Charles hit .296 with 13 home runs. That performance convinced the Braves that he should return to Triple-A ball in 1958.

Charles reported to Wichita, but this time he saw overt racism coming from a member of the team’s coaching staff. During one workout, left-hander Juan Pizarro hurt his leg, affecting his ability to run wind sprints at full speed. The coach approached Pizarro, a dark-skinned native of Puerto Rico, telling him that if he didn’t want to run hard, he could “go back to Africa.” The incident not only bothered Pizarro, but it badly affected Charles, who was so upset that he considered quitting baseball. He called his grandfather, a Baptist minister, to ask him his advice. His grandfather told him to sleep on it, and then make a decision in the morning. Charles did just that. Recalling the perseverance of Robinson, Charles decided that quitting was not the right option.

For the next four years, Charles remained stuck at Triple-A, though in different cities. He played for Wichita, Louisville, and Vancouver. During this span, Charles made the transition from the middle infield – he had played both shortstop and second base – to third base. He would play his new position spectacularly. As a third baseman, he twice led his minor league in putouts.

In 1960, Charles attended Spring Training in Bradenton, Fla., where the Louisville Colonels prepared for the season. There he encountered a young pitcher named Pat Jordan, who would gain far greater fame for his work as an author. In 1975, Jordan wrote the critically acclaimed book, A False Spring, in which he speculated about Charles’ true age. “He seemed incredibly old to me then,” Jordan wrote. “He had a few wiry strands of gray hair, which I assumed revealed him to be much older than he admitted.” According to all available resources, Charles was only 27 at the time, but Jordan felt that he had already reached his thirties.

Charles’ age may have been a mystery to some, but it was his inconsistent hitting that kept him out of the major leagues, and buried at Triple-A. Charles also faced another problem, one over which he had no control. The Braves already had an All-Star third baseman in Eddie Mathews, the Braves’ left-handed complement to Hank Aaron. Even though Mathews batted left-handed, there was no chance that Charles would beat him out for the everyday job at the hot corner, let alone earn a platoon with the future Hall of Famer.

No one reasonably could have blamed Charles if he had given up the dream. But Charles was not ready to stop fighting. As someone who admired the example of Jackie Robinson, a player who refused to give up, Charles felt motivated to keep plugging away. He worked hard on his hitting, showing major improvement in 1961. He posted a career-best OPS of .848, hit for both power and average, and led the Pacific Coast League in runs scored.

Some writers speculated that Charles would become the Braves’ primary utilityman in 1962, but an even bigger break came his way that winter. The Braves traded their veteran minor leaguer, sending him to the Kansas City Athletics for infielder Lou Klimchock and pitcher Bob Shaw. The 1962 A’s, managed by Hank Bauer, needed help in numerous areas, none more so than at third base. When the regular season opened, the 28-year-old Charles found a spot on the major league roster. He began the season on the bench, but was no longer blocked by a player the caliber of Mathews.

An early-season slump by Wayne Causey gave Charles the chance to play every day at third. So Bauer turned to his 29-year-old rookie, who rewarded the show of confidence by hitting 17 home runs, stealing 20 bases, and forging an OPS of .811. Just like that, Bauer had found his new third baseman. In his second season, Charles did not hit quite as well, but he remained productive, with 15 home runs and 58 walks. He also played a stellar third base, where his good hands and strong range made him one of the league’s best corner infielders.

In 1964, Charles’ batting average fell off to .241, the first red flag of his career in Kansas City. In 1965, his home run output fell by half, in part because of increased dimensions at Municipal Stadium, but he still managed to improve his on-base and slugging percentages. Then came another solid season in 1966; even though he hit only nine home runs, he batted .286 and reached base 33 percent of the time. For five years, Charles had given the A’s above-average play out of the third base position.

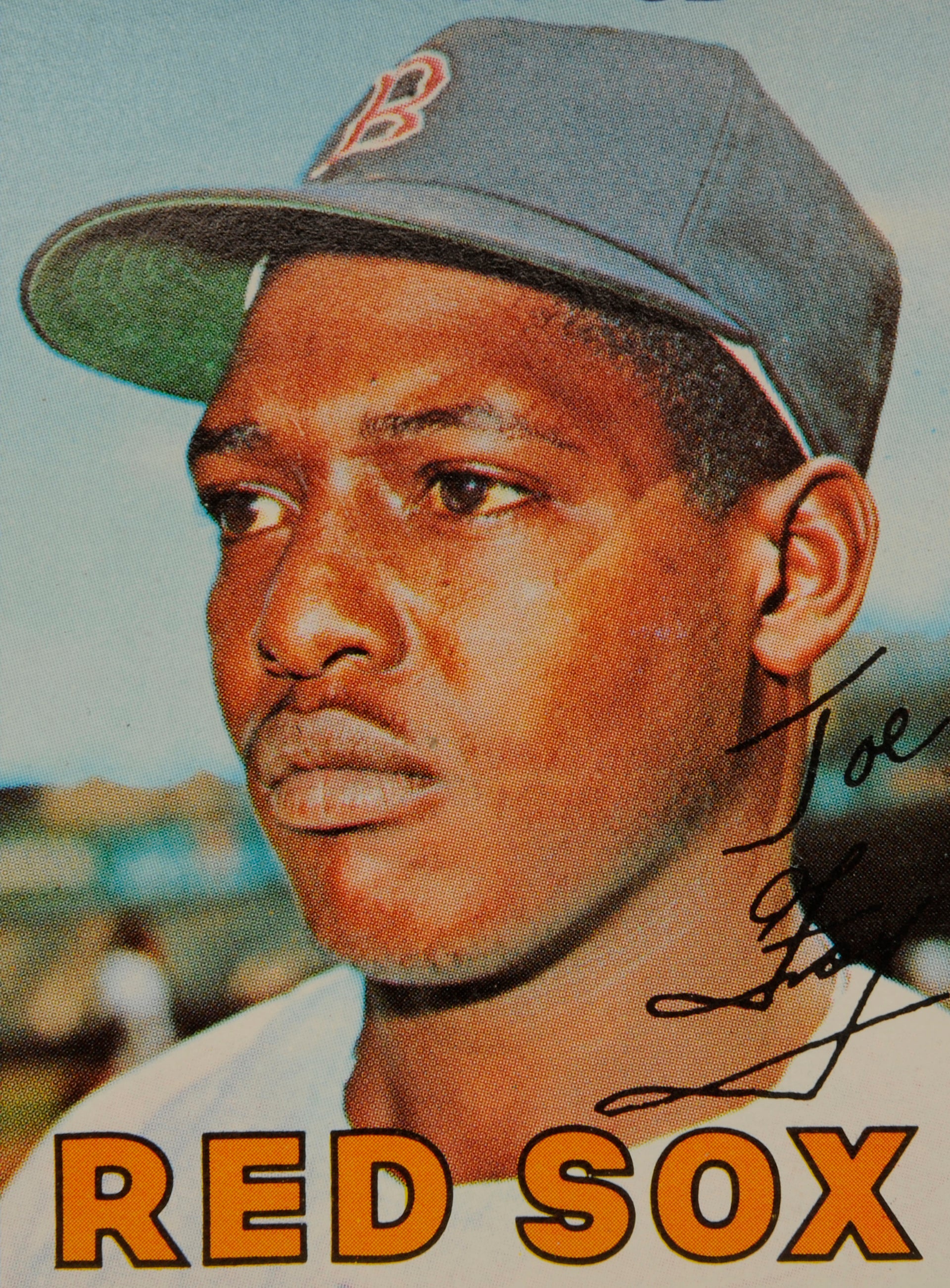

In 1967, a slow start at bat resulted in Charles losing his job to Danny Cater. To make matters more ominous, a young Sal Bando was primed to complete his minor league apprenticeship and make the jump to Kansas City. At 34, Charles was becoming a liability for the A’s. On May 10, the A’s traded their third baseman, sending him to the New York Mets for little-known outfielder Larry Elliot and $50,000 in cash. The Mets eventually made Charles their starting third baseman, replacing the aging Ken Boyer.

With the Mets, Charles also received national attention for his abilities as a poet – some called him the poet laureate of baseball – but the trade failed to rejuvenate Charles’ on-field game. He hit only .238 with three home runs, prompting the Mets to waive him after the season. Yet, Charles’ tenure with the Mets had not come to an end.

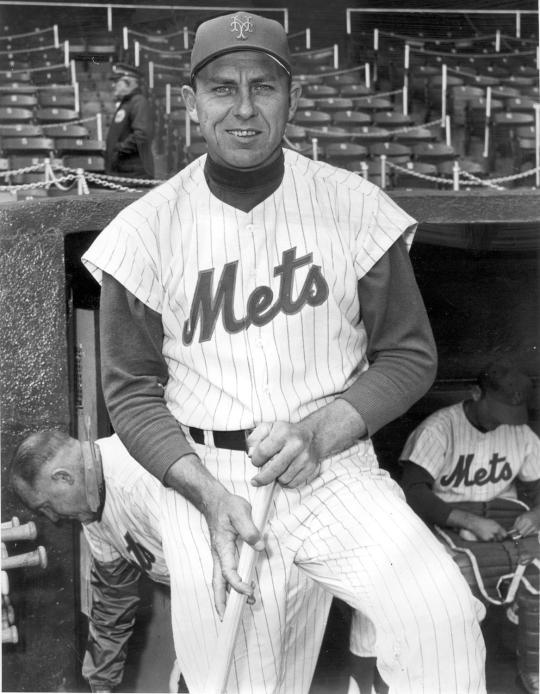

In 1968, the Mets invited him to Spring Training as a non-roster player. Charles took the offer, reported to spring camp, and so impressed new Mets manager Gil Hodges that he made the team. He also regained his role as the club’s starting third baseman.

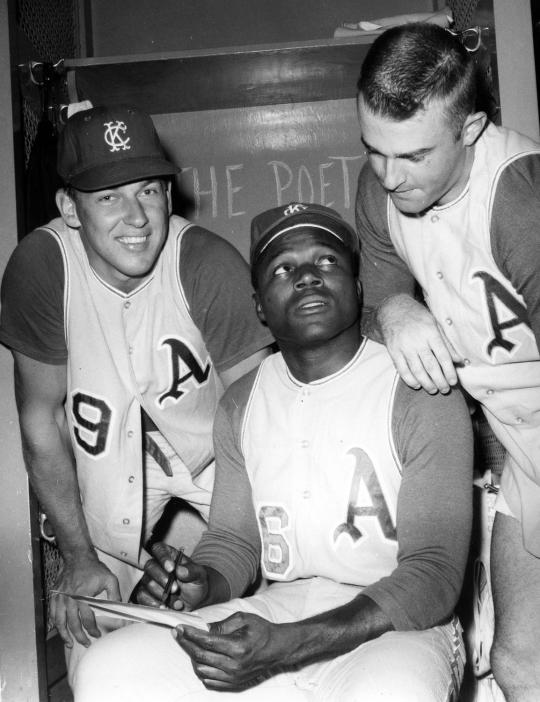

Ed Charles, pictured above with Roger Repoz (left) and Dan Cater in 1966, wrote poetry and was known as "The Poet." (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

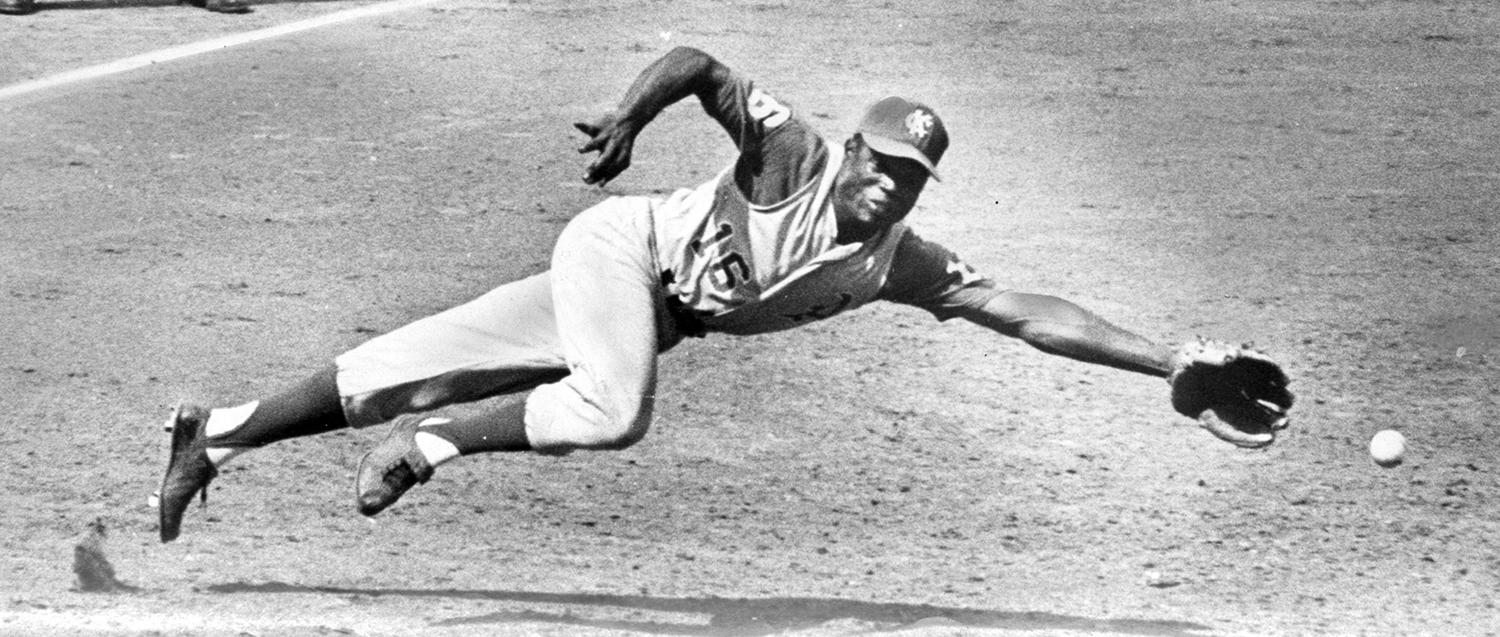

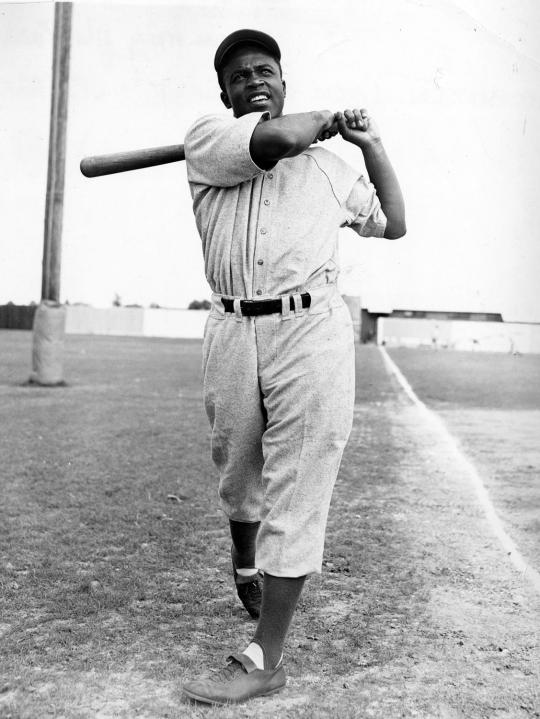

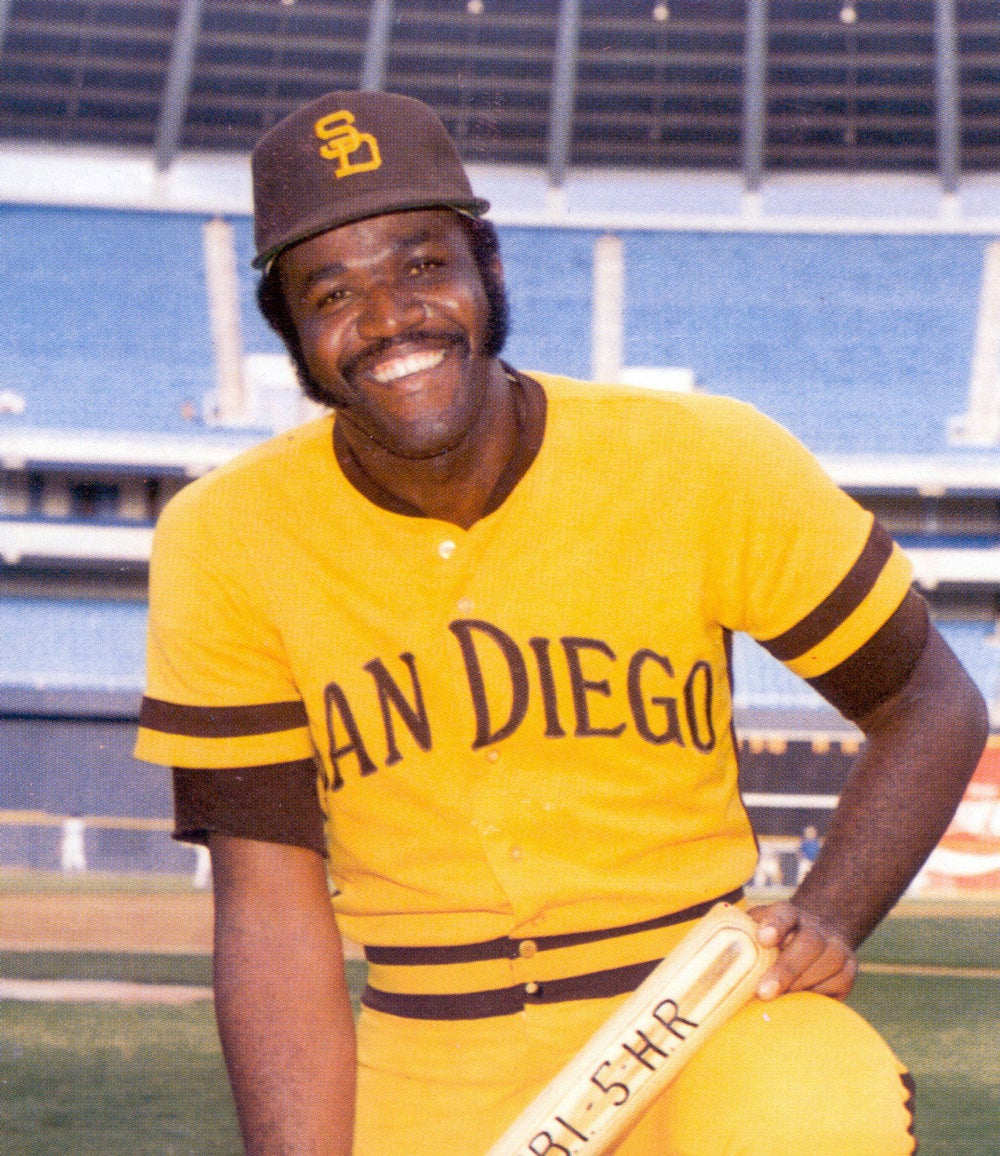

Ed Charles worked with Amos Otis while both were with the Mets as Otis worked at becoming a third baseman. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

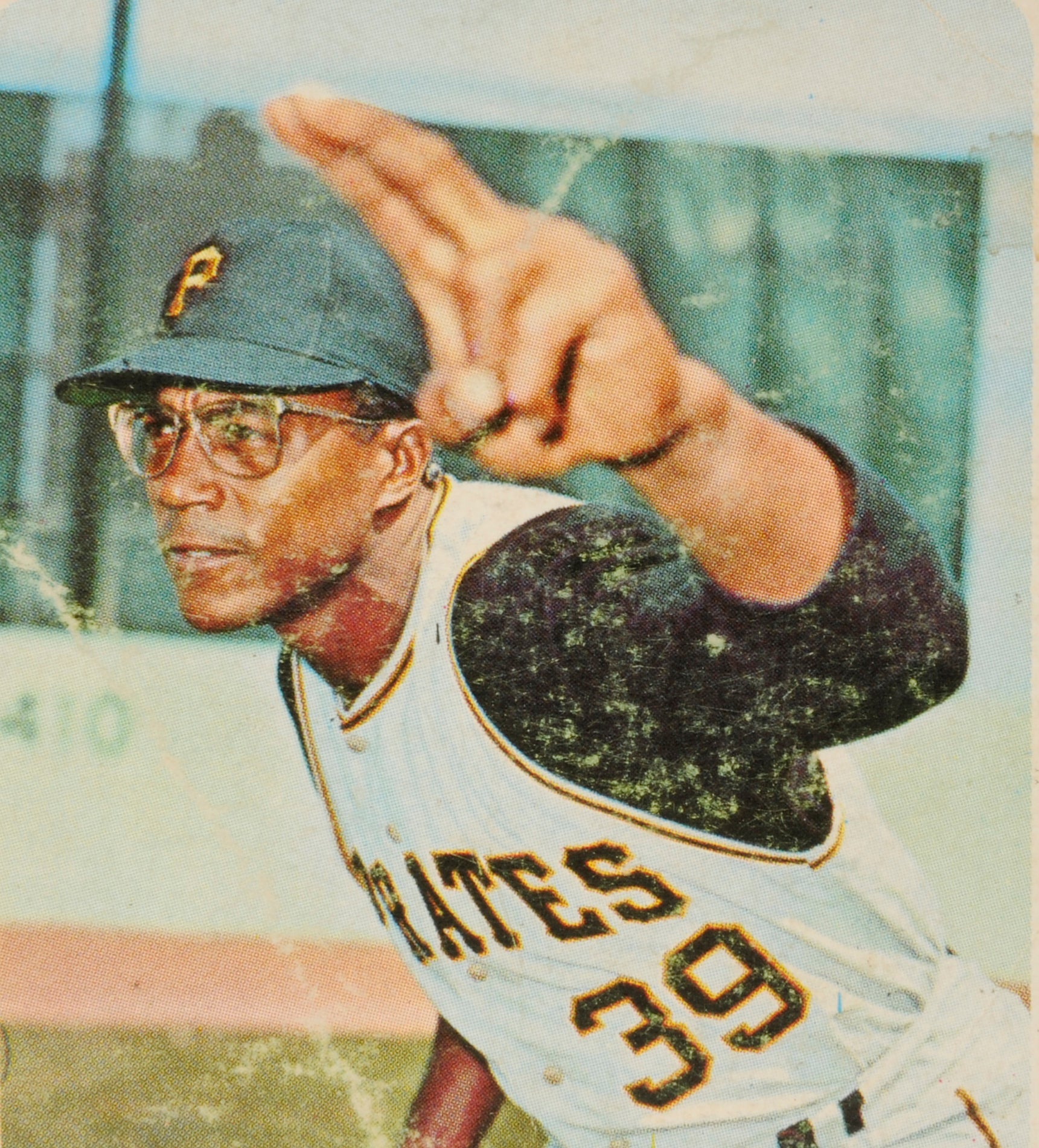

Ed Charles played third base so smoothly and ran so gracefully that teammate Jerry Koosman (pictured above) began calling him “The Glider.” (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

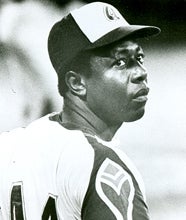

Although Ed Charles reported to Mets Spring Training camp as a non-roster player in 1968, he impressed new Mets manager Gil Hodges (pictured above) so much that he made the team. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

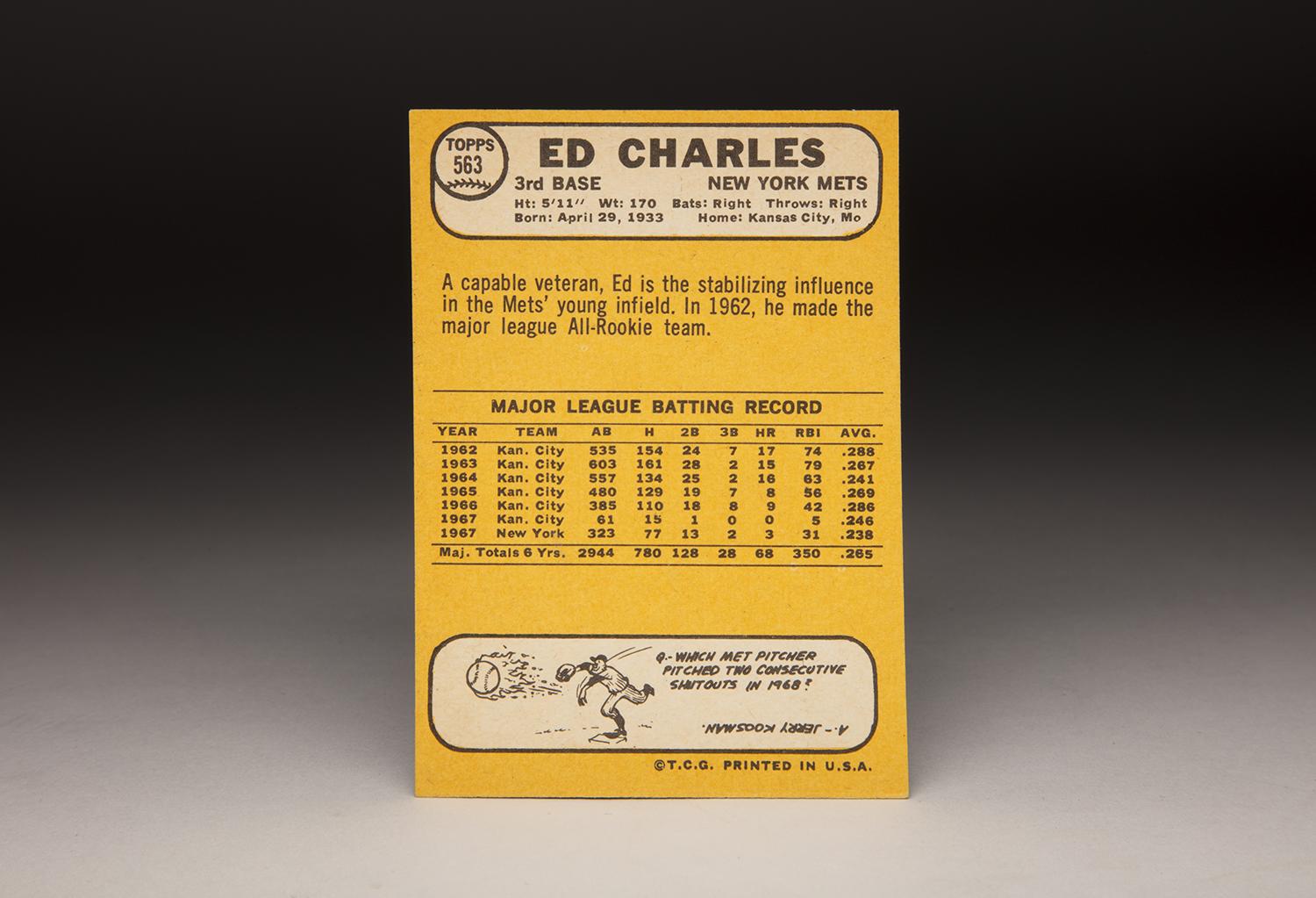

At 35 years of age, a resurgent Charles batted .276 with 15 home runs and a respectable OPS of .761. Given the extreme pitcher-friendly conditions of 1968, Charles’ numbers were highly respectable.

Charles’ defensive play and baserunning style also drew special attention in New York. He played third base so smoothly and ran so gracefully that teammate Jerry Koosman began calling him “The Glider.” The nickname stuck.

Now established in New York, Charles began the 1969 season at third base, but his hitting tailed off so drastically that he fell into a platoon with rookie Wayne Garrett. At 36, Charles batted only .207 with three home runs, but did provide leadership for the Mets, a team heavily reliant on players in their 20s.

One of the Mets that he took under his wing was a young Cleon Jones, a talented young outfielder who sometimes drew criticism for a failure to hustle. He also worked with Amos Otis, whom the Mets tried to convert into a third baseman, but Otis resisted the move.

Even though his offensive game became almost nonexistent, Charles remained an excellent third baseman. After not appearing in the NLCS against Atlanta, he scored the game-winning run in Game 2 of the World Series and fielded his position flawlessly, as the Mets surprised the world with a five-game upset of the power-packed Baltimore Orioles. He also drew praise from his World Series counterpart with the Orioles, a fellow named Brooks Robinson.

“He was an underrated third baseman in this league [the American League],” Robinson told New York Newsday, “And he’s shown us he’s still capable of playing as well as he did years ago. I don’t care how old he is.”

The Mets, however, did not heed Robinson’s words. Only a few days after the Mets completed their World Series upset, they handed a piece of bad news to Charles. They told him they wanted to make a change at third base, necessitating his unconditional release. The Mets offered him a non-playing position in the organization.

Now 36 years of age, Charles initially accepted the Mets’ offer to work in their promotions department, but a dispute with Mets general manager Johnny Murphy resulted in him later turning down the offer. Charles also decided against pursuing a contract as a bench player with another team.

After eight hard-fought years of major league service time, Charles called it a career. There would be no Topps card in 1970.

A man of numerous talents, Charles did not have to rely on baseball to keep himself busy. At first, he embarked on a USO tour of military hospitals in the Pacific, where his warm personality helped boost the morale of Vietnam soldiers. Upon returning, he tried his hand at producing music for Buddha Records, later worked in the furniture business, and continued his efforts at writing poetry.

In 1972, only three years after the Mets’ World Series title, Charles came upon one of his greatest thrills when he happened to meet one of his heroes for the first time. The excellent film, 42, suggests that Charles met Jackie Robinson when he was a young boy growing up in Florida, but that is a fictionalized account.

Their first meeting, just by happenstance, occurred at the New York City office of the Small Business Administration, where Charles was filling out paperwork. He noticed Robinson in the room with him. Battling back nerves, Charles walked over to Robinson, identified himself, and thanked the Hall of Famer for his efforts in breaking down the game’s racial barrier 25 years earlier. Robinson smiled, responding, “That means a lot to me.” Sadly, Robinson would die later that year; he and Charles would never meet again.

In 1973, Charles decided to return to baseball. He became a scout and minor league coach with the Mets’ organization, remaining in those capacities until 1985. Charles believed that the Mets were grooming him to become their director of community relations, but a dispute resulted in the job going to another candidate. Feeling betrayed, and suspecting that race was involved in the decision, Charles left the Mets’ organization.

In the late 1980s, Charles found a line of work that suited him best: working with kids who had run into trouble with the law. He joined the Department of Juvenile Justice, which assigned him to work at a detention center in the Bronx. Putting in 12-hour shifts with the troubled youngsters, many of African-American heritage, Charles oversaw their behavior, making sure that they stayed away from drinking and drug use. For a caring man like Charles, this career pursuit became a natural.

For him, it was a chance to pass the torch to the next generation, much like Jackie Robinson had laid the groundwork for subsequent generations of African-American ballplayers. Like Jackie, Ed Charles succeeded very well. He passed away on March 15, 2018.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame