- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Steve Barber

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Steve Barber

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

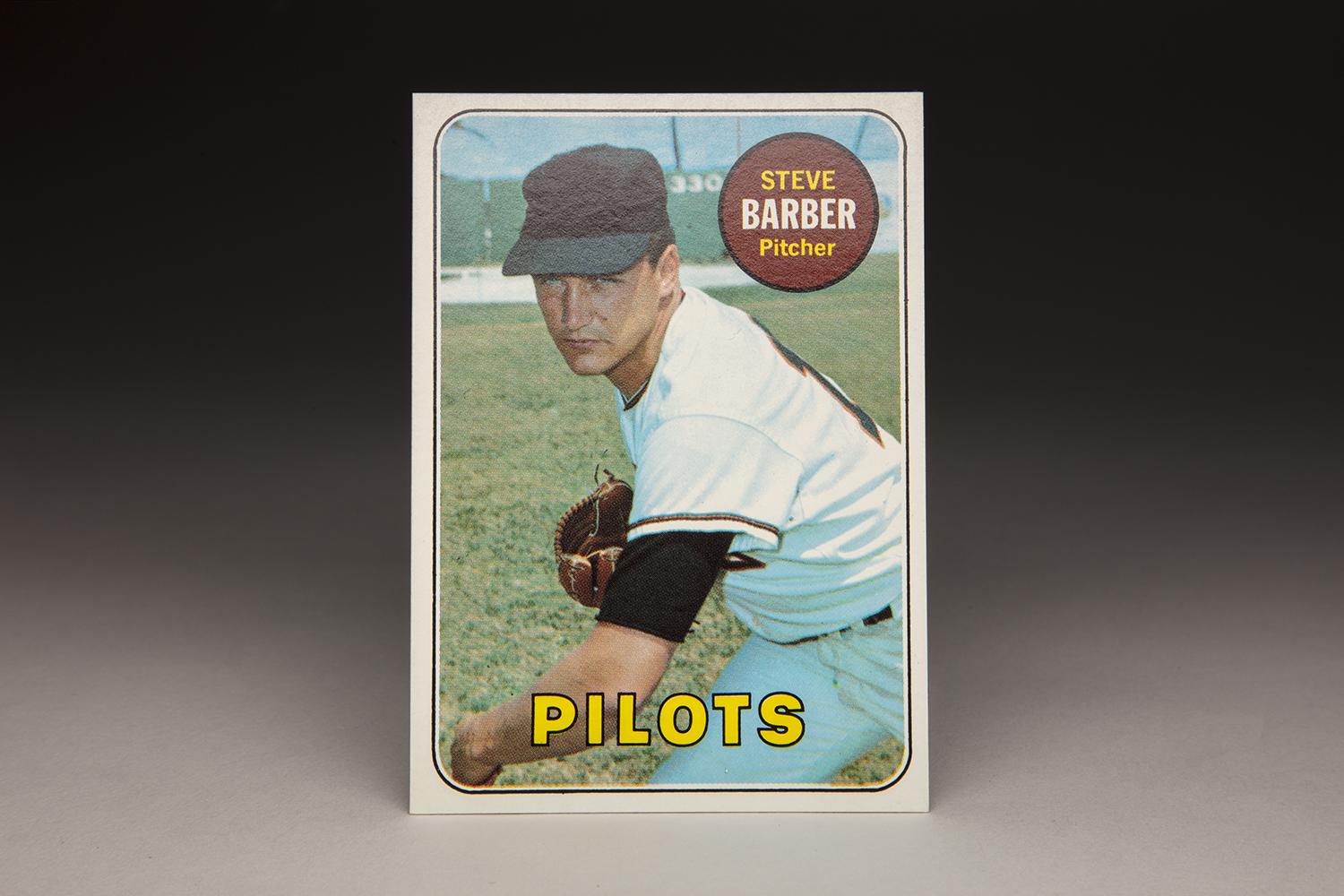

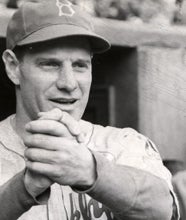

At first glance, it might appear that Steve Barber is trying to hide himself from the photographer on his 1969 Topps card.

As he finishes off his simulated delivery, his cap is pulled down over his head, thereby preventing us from seeing the entirety of his face. Given the state of his career in 1969, it might be understandable that Barber didn’t want to be seen. Injuries had wrecked his left arm, the situation reaching such a dire state that he was simply hoping to latch onto a bullpen spot with an expansion team, the meager Seattle Pilots.

In reality, we’re reading far too much into this baseball card. Although the card was issued in 1969, the photograph is actually from at least two years earlier, when Barber was still pitching for the Baltimore Orioles. That’s because major league players were refusing to sit for new baseball card photographs, in the hopes that their negotiations with Topps might yield a better contract.

On this card, the Orioles’ logo on Barber’s cap has been wiped out, and the angle of the photograph prevents us from seeing the team name on the front of his jersey. At this time, Topps did not resort to airbrushing, so we don’t even see an attempt at creating the light blue colors of the Seattle Pilots. Topps would not really rely on airbrushing until the 1970s, when it became something of a mad science for the card company.

Steve Barber's 1969 Topps Card doesn't show a logo for any particular team, as the photo was likely taken about two years earlier when he was still with the Baltimore Orioles. Barber spent the 1969 season with the Seattle Pilots. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

In all likelihood, this photograph was taken during Spring Training in 1967, when the Orioles were preparing for the season in Miami. At this point, Barber was coming off a decent year, one in which he had posted a record of 10-5 and a 2.30 ERA, albeit in a season that was shortened by injury.

It was those arm problems that had really begun to manifest themselves during the summer of 1966. Barber would never be the same again. In 1967, Barber was struggling so much that he had actually piled up more walks than strikeouts. In July, the Orioles gave up on Barber, sending the left-hander to the New York Yankees for backup first baseman Ray Barker and a player to be named later. That trade signaled the beginning of the vagabond stage of Barber’s career.

Yet, we are getting ahead of ourselves here. Barber’s baseball story began more than a decade earlier, when he drew the attention of many big league scouts, including those associated with the Orioles. As a high school pitcher in Silver Springs, Md., Barber threw remarkably hard. The fact that he was left-handed made him all the more attractive. In the spring of 1957, the hometown Orioles succeeded in signing the 18-year-old out of high school.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Orioles assigned the teenaged phenom to Class D ball, the lowest level of minor league ball at the time. Except for a brief call up to Class C, Barber remained there for three consecutive seasons.

Why did Barber remain buried in the lower minor leagues? First, he struggled with a lack of control. He had an incredible fastball, but literally had no idea where it was going. If other pitchers were conveniently wild, it should be said that Barber was phenomenally wild. The other problem involved his temper. Given his perfectionist tendencies, he tended to become angry when he did not pitch well, or when his teammates did not perform suitably behind him.

In 1958, Barber’s career appeared to have completely stalled. Still pitching in the lower minors, he lost 12 of 18 decisions, walked 166 batters in 166 innings, and posted an ERA of 5.42. No one would have blamed the Orioles for giving up and releasing Barber right then and there.

The Orioles decided to give Barber another look in 1959. That’s when Barber turned the corner. Pitching for Pensacola of the Alabama-Florida League, he improved his control slightly, as he lowered his ERA to the 3.80 range. The Orioles saw enough to give him a late-season recall to Amarillo of the Double-A Texas League. The turnaround continued in winter ball, where he did hands-on work with one of the Baltimore’s coaches.

“Winter ball helped a lot,” Barber told sportswriter Phil Pepe. “I played at Clearwater under [manager] Luman Harris and my control improved.” Harris, who would later manage the Orioles, the Houston franchise, and the Atlanta Braves, also helped Barber control his temper and curb his tantrums in reaction to fielding errors and questionable calls from the umpires.

By the spring of 1960, Barber had stopped losing his temper. His control was improving, too. Even though he reported to Spring Training as a non-roster player, Orioles manager Paul Richards took a close look at Barber and liked what he saw. At the end of Spring Training, Richards included Barber on the Birds’ Opening Day roster.

“He has a great arm,” Richards told Pepe. “His big problem was his temperament and general deportment, but he’s got that under control now.”

In late April, Barber moved into the Orioles’ starting rotation. He became part of Baltimore’s vaunted “Baby Birds” pitching staff, which talented young hurlers in Milt Pappas, Jack Fisher, Chuck Estrada and Jerry Walker. Of the group, Barber threw the hardest; he also put up the lowest ERA but won only 10 games due to a lack of run support. On the down side of the ledger, he continued to exhibit several streaks of wildness. He led the American League in wild pitches (with 10) and the major leagues in walks (with 113).

It was during that 1960 season that Barber’s fastball was officially measured. The device being used clocked his fastball at 95 and a half miles an hour, the third fastest mark on record at that time, behind only Hall of Famers Walter Johnson and Bob Feller. While 95 miles an hour might not sound overwhelming in today’s game, it should be pointed out that an average fastball in the 1960s fell into the range of only 85 to 87 miles an hour. It’s also possible that the measuring devices of the 1960s might have been slow, compared to the more accurate readings that radar guns provide today.

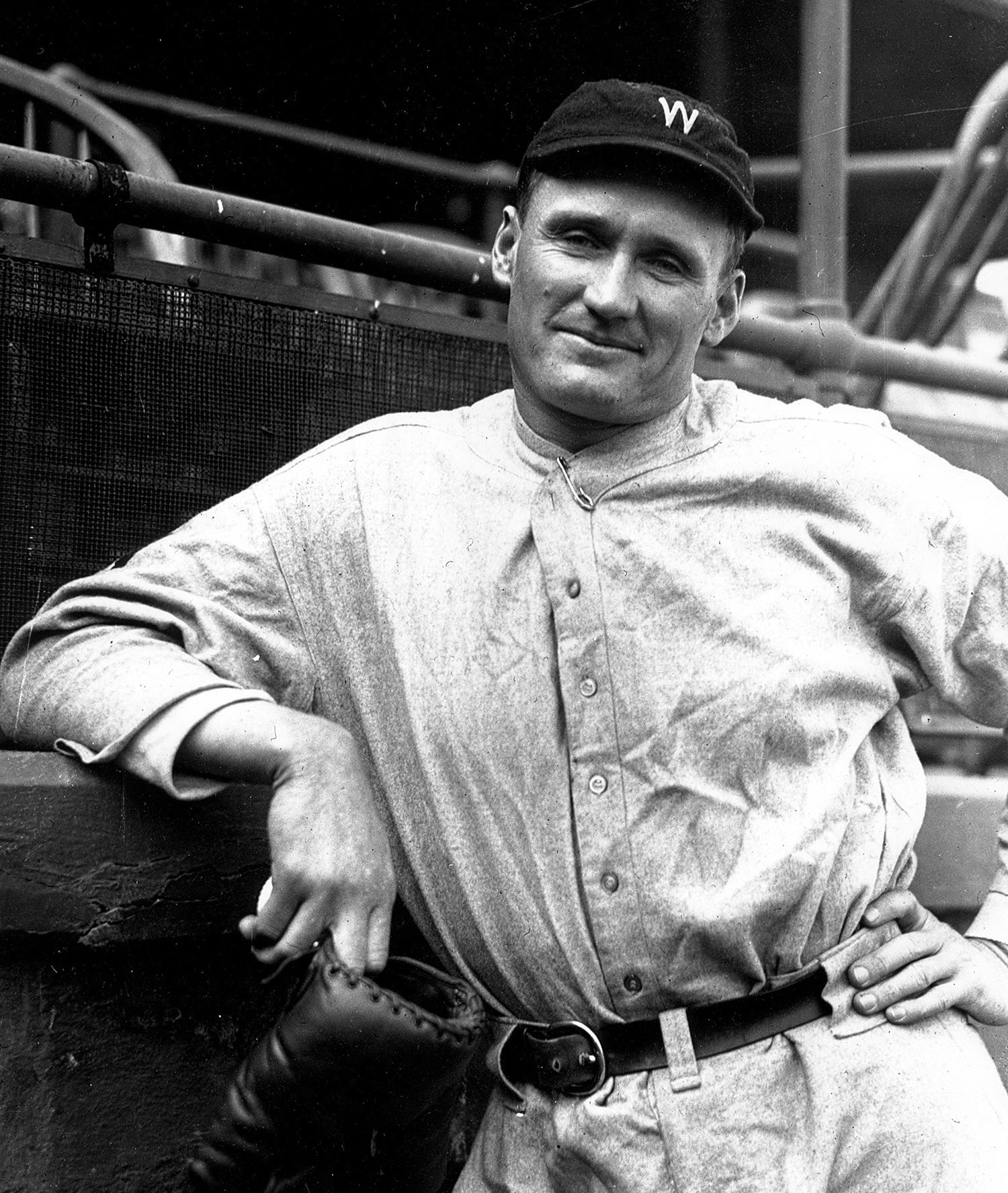

With his rookie season in the books, Barber became a durable and reliable starter for the Orioles over the first half of the decade. From 1961 to 1966, he won a total of 81 games, including a 20-win season in 1963. He also earned All-Star Game selections in ’63 and ’66. He was never better than in ’63, when he logged 258 innings, struck out 180 batters and put up an ERA of 2.75.

During that same span, Barber established a reputation as the game’s hardest thrower. Not only did Barber impress with sheer velocity, but he also featured a sinking fastball that darted in and out, and felt very heavy on the hands of the hitter. As one of his catchers once said, trying to hit a Barber fastball was like swinging “at a ball of iron.” Longtime Orioles center fielder Paul Blair said a Barber fastball “was like a brick. He was heavy to catch.” Given the velocity and heaviness of the fastball, Barber became an uncomfortable at-bat for just about every American League hitter.

Steve Barber played for the Baltimore Orioles from 1960-1967. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Barber continued to pitch well over the first half of the 1966 season, emerging as the Orioles’ ace and earning his second All-Star Game selection. Unfortunately, he came down with tendinitis in his elbow after the All-Star break. Ever the gamer, Barber tried to pitch through the pain, but the condition worsened. In August, the Orioles shut him down, forcing him to miss the balance of the regular season, along with Baltimore’s appearance in the World Series. Barber did pick up a World Series ring for his efforts, but missing the Fall Classic stung the young pitcher.

In 1967, Barber attempted a comeback. In his first start, he appeared completely recovered, throwing eight innings of no-hit ball before surrendering a hit in the ninth. Later in April, he pitched the most memorable game of his career. Facing the Detroit Tigers, Barber walked 10 batters, but allowed no hits. In fact, Barber and reliever Stu Miller combined on a no-hit game, but wild pitches by both pitchers and an Orioles fielding error combined to produce a 2-1 loss. Barber threw 144 pitches that day, many of them balls and most of them unhittable. It was classic Barber.

As well as Barber pitched in those starts, he struggled in most of his other outings in 1967. By July, the Orioles decided to move on and traded him to the Yankees. For Barber, the deal provided welcome relief.

“Naturally, I was a little surprised to be traded at this time, but I have been asking them to trade me for three years,” Barber told Yankee beat writer Jim Ogle. “It was just that I felt that would be better off in a new town.”

Barber claimed that his arm felt fine. He finished out the season in New York but endured another difficult campaign in 1968, thanks to a midseason demotion to Syracuse of the International League. After the season, the Yankees chose not to protect Barber from the expansion draft, allowing the Pilots to take him.

In joining the 1969 Pilots, Barber became one of the most notable characters in Jim Bouton’s iconic book, Ball Four. Bouton portrayed Barber in somewhat of a nefarious way, suggesting that he was hiding an injury to his arm in order to maintain his presence on the roster. By doing so, Bouton claimed, Barber was denying a younger pitcher the chance of pitching for the Pilots.

In retrospect, Bouton’s portrayal of Barber seems unfair. Like Barber, Bouton had hurt his arm, and like Barber, was doing all he could to preserve his career. Barber spent more than his fair share of time in the trainer’s room, but at least he was making an effort to pitch, rather than just putting in idle time on the disabled list.

Bothered by elbow pain, Barber ended up splitting the 1969 season between the bullpen and the rotation, but never gained traction. After the season, the Pilots relocated to Milwaukee, but Barber didn’t make the move with his teammates. On April 1, 1970, just one week before Opening Day, the newly minted Milwaukee Brewers released Barber.

Later that month, Barber found work with the Chicago Cubs, where he pitched out of Leo Durocher’s bullpen. Now 32 and his arm in near tatters, Barber didn’t show the Cubs much in five games. In late June, they released him. He signed on with the Atlanta Braves, where he was reunited with manager Luman Harris, and remained with the organization through the middle of 1972.

Released by the Braves that summer, Barber latched on with the California Angels and pitched well in middle relief. After the season, the Angels included him as a throw-in to a larger trade with the Brewers, but once again he never made it to Milwaukee; the Brewers released him during Spring Training. From there, he signed on with the San Francisco Giants, where he pitched briefly before drawing his release in August of 1974.

His playing days over, Barber decided to leave baseball completely. He eventually moved to Las Vegas, where he chose one of the noblest of professions: Serving as a school bus driver for children with disabilities. He remained in the job for several years, right up until the time in 2007 that he fell ill with pneumonia. A few days after being admitted to the hospital, Barber passed away. He was 67.

It’s hard to believe that occurred 10 years ago. I remember hearing about Barber’s death, and it had an impact on me, in part because of the baseball cards I have from the latter days of his career. When a player dies, I tend to think of his baseball cards, and how he looked on them. In Barber’s case, his 1973 card with the Angels and his 1974 card with the Brewers came to mind.

A quick examination of Barber’s 1969 card, with the Orioles logo and name obliterated from sight, and the Pilots designation at the bottom, reminds us of the fortunes of a journeyman ballplayer. Like a lot of journeymen, Barber is not particularly well remembered today. But at one time, he was a phenom. And at one time, no one threw the fastball any harder than Steve Barber.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame