- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tom Phoebus

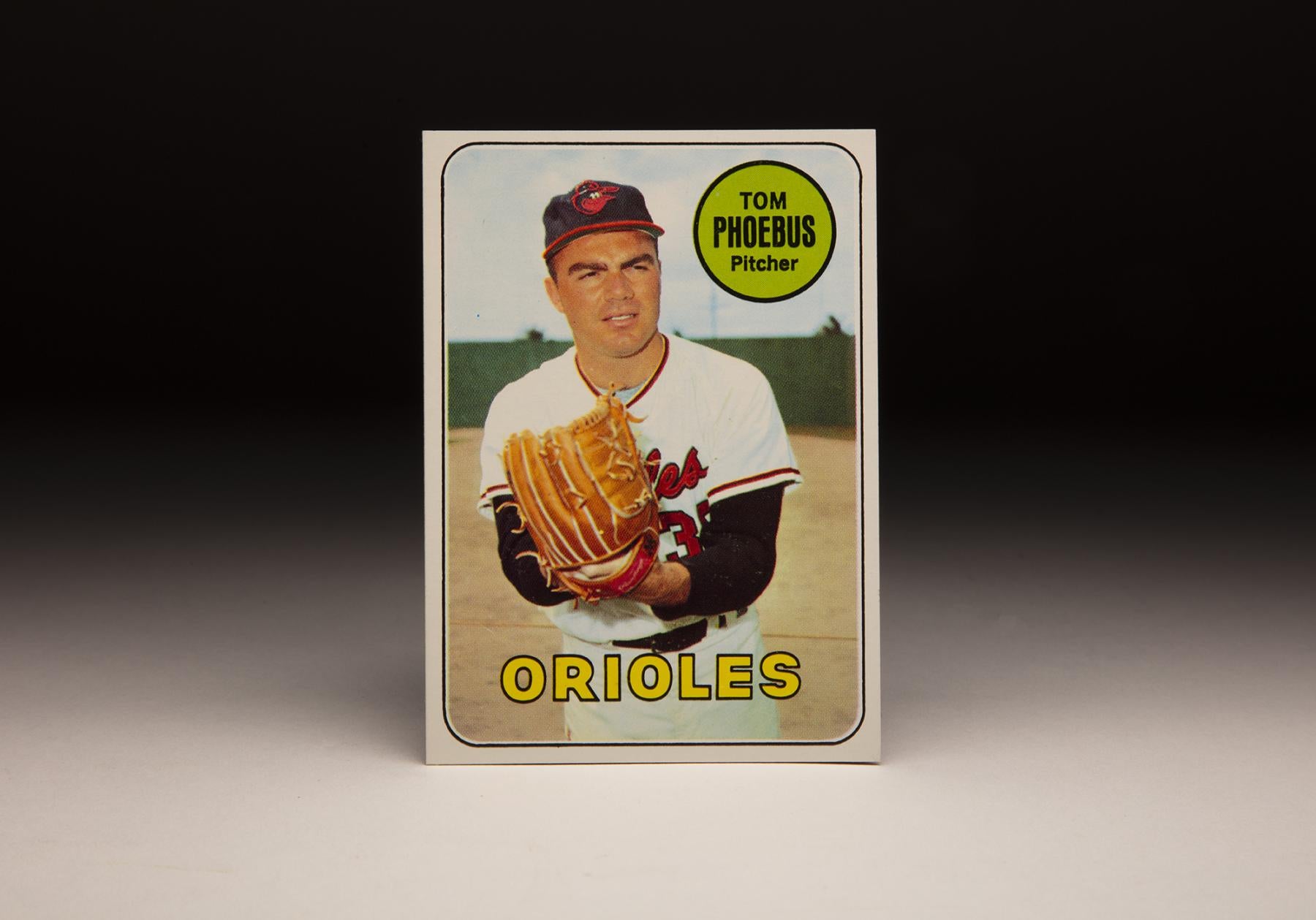

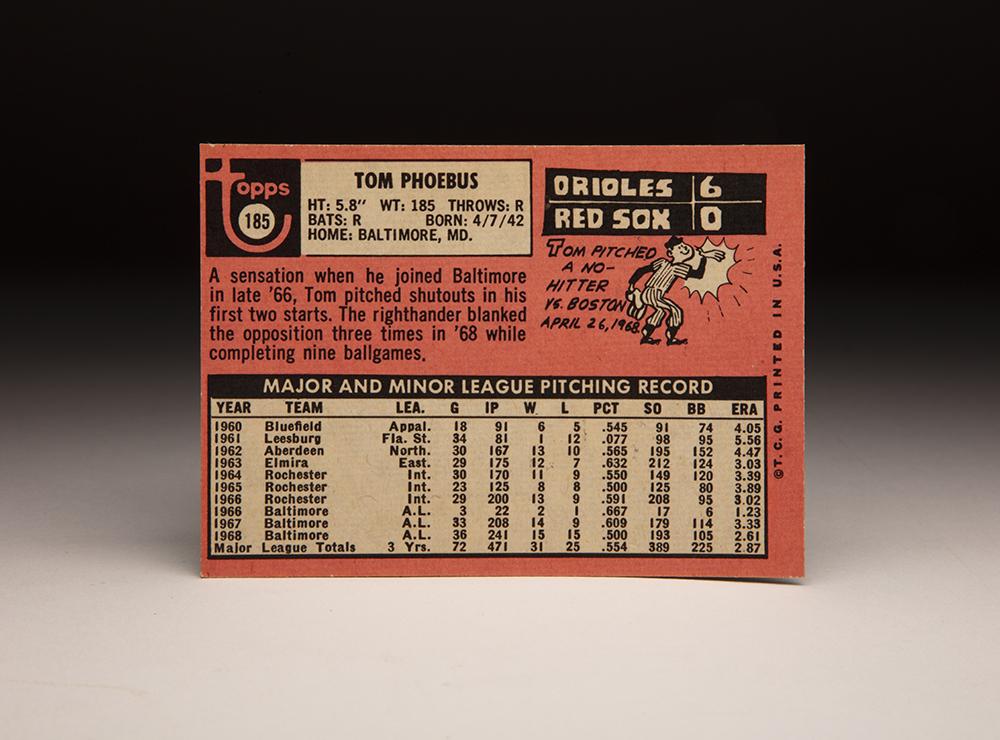

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Tom Phoebus

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

I can’t say that I remember ever seeing Tom Phoebus pitch in a major league game.

His last season was 1972, the year that I started following baseball. But I do remember his baseball cards, beginning with his last card, issued in 1972. That showed him as a member of the San Diego Padres, a team with which he struggled. His prime years came with the Baltimore Orioles, the team with which he is depicted on all of his other Topps cards. It is those cards that have stayed with me over the years.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Phoebus died earlier this month at the age of 77. He was not a household name in baseball; in fact, he has mostly become forgotten with the passage of time. But his name sticks with me, and other fans who grew up with the game in the early 1970s, in part because of the unusual nature of his last name.

We always struggled with the pronunciation of that name: Phoebus. We wondered how to pronounce it? Was it FOE-bus? Or FAY-bus? No, it was actually FEE-bus. When we realized that was the pronunciation, it sounded funny, partly because it sounds like “feeble.” I wonder if Phoebus had to endure jokes about the name during his career, and before that, during his childhood.

In actuality, Phoebus was anything but feeble. No, at his peak, he was a power pitcher who piled up strikeouts and had the stuff to throw a no-hitter. At one time, the Orioles viewed him as one of their future aces, a young pitcher they held in almost the same high regard as the more established Jim Palmer and Dave McNally.

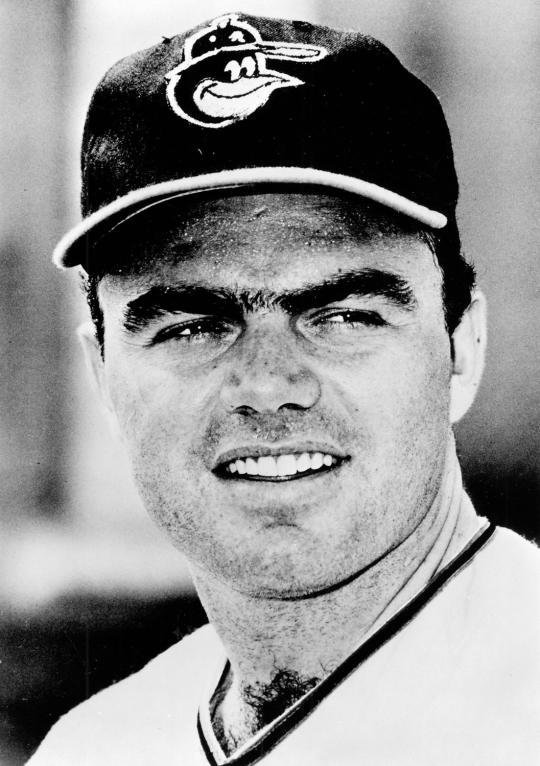

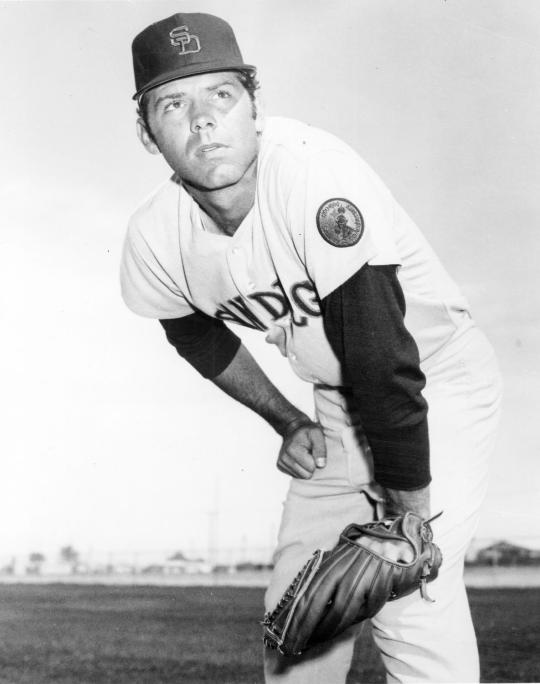

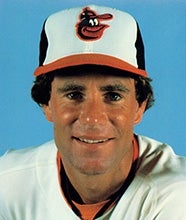

Of the Phoebus cards I’ve seen, my favorite is the one from 1969 Topps. It gives us a good look at his thick eyebrows, as he peers intently toward his imaginary catcher. Fully evident is the shape of his head, which appears almost rectangular, along with his heavy jowls, and his thick neck.

It’s a good shot of Phoebus, but it doesn’t convey his height; he was all of 5-foot-8, a size that is almost unheard of for a pitcher in today’s game.

While Phoebus lacked height, he didn’t lack stuff on the mound. His best pitch was a crackling curve, but he also threw a slider that would make batters bend at the knees, and a plus fastball. With better control, he might have had a longer career.

Just as interesting as the image of Phoebus is the background to the photograph. This looks to be a Spring Training photo, taken at the Orioles’ site in Miami, or somewhere near it, back in 1966 or ’67. The ballpark, or practice field, looks rather barren. All that’s evident is a green fence and dirt – lots of dirt. Or is it sand?

By the way, where is the grass? There is not a patch to be found. Take away the fence, and you could imagine this photograph being taken at a Florida beach on an overcast day. Whatever the location, it’s not the usual Spring Training background we’ve come to expect from so many Topps cards over the years.

The background of the card is certainly not typical, and neither was Phoebus’ career in the professional ranks. His journey to the major leagues began nine years before this card came out, back in 1960, when the Orioles signed him as an amateur free agent. A native of Baltimore, Phoebus naturally drew the attention of the hometown Orioles, who were captivated by his right arm and his dominance of high school competition. Duly impressed, and not at all scared off by his short stature, the Orioles gave Phoebus a bonus of $10,000 to sign with them. For Phoebus, the opportunity to sign with the Orioles fulfilled a dream that he had held throughout his childhood.

Although Phoebus was highly touted, he struggled mightily over his first three minor league seasons, failing to register an ERA better than 4.05. He was wild, especially so at Class C Aberdeen in his third pro season. In 167 innings, he walked 154 batters, a number that is reminiscent of another Orioles farmhand of the era, the legendary Steve Dalkowski.

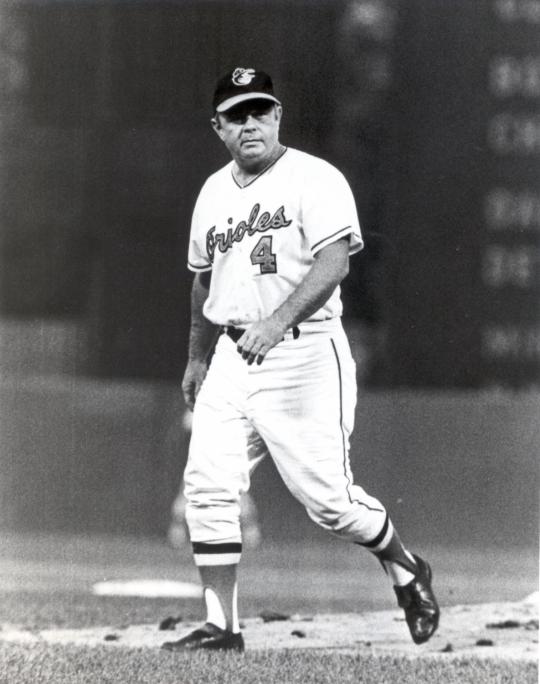

In spite of his control problems, the Orioles moved Phoebus up to Double-A Elmira in 1963. Facing tougher competition, he enjoyed a breakthrough while pitching under his new manager, a fellow named Earl Weaver. His walk total remained high (124), but he also struck out 212 batters and lowered his ERA to a more-than-respectable 3.03.

The Orioles liked what they saw and gave him another promotion, this time to Triple-A Rochester. With the Red Wings, he walked 120 batters, still a concern, but posted an ERA of 3.39 while winning 11 games against the elevated competition.

In 1966, Phoebus hoped to make the Orioles out of Spring Training, but was disappointed when he received a return ticket to Rochester. The Orioles felt that he needed additional minor league time in an effort to curb his control. That decision turned out prescient, as Phoebus’ walk total fell under 100 for the first time in four seasons. Phoebus drew kudos from Weaver, who was now managing him in Rochester.

“He has major-league pitches,” Weaver told the Sporting News. “Everybody in the organization knows this. It’s just that he must prove that he can throw strikes consistently… I think he has an excellent chance to pitch for Baltimore next year.”

In August, Phoebus pitched a no-hitter for the Red Wings, a powerhouse of a club that featured 18 future and former major leaguers. Phoebus’ gem prompted members of the “Tom Phoebus Fan Club” to stage a “protest” in his old neighborhood in Baltimore. Holding up signs and chanting, they wanted their hometown hero to receive an immediate promotion to Baltimore, no easy task on a team that already had Palmer, McNally, Wally Bunker and Steve Barber. It was not a protest of anger, but rather a friendly one, conducted mostly by his friends and family.

The Orioles resisted the protest – at least for a month. After the minor league campaign came to an end in early September, the Orioles brought the young right-hander to Baltimore during the final month of the season.

As the Orioles ran away with the American League pennant, Phoebus opened up eyes throughout the league. In his major league debut, he pitched a shutout, capped off by a game-ending strikeout. The fans at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium treated him to a standing ovation.

Phoebus made two more starts, including one more shutout. Although he was not eligible for World Series play, he certainly made an impression in his regular season cameo.

In 22 innings, he struck out 17 batters against only six walks. His teammates also took notice, dubbing him “Fireplug” because of his height and his toughness.

On the strength of that late-season showcase, Phoebus made the Orioles’ Opening Day roster in 1967, moving right into their starting rotation. As a team, the ’67 Orioles suffered a letdown after their World Series triumph, but Phoebus certainly shared none of the responsibility for that. Quiet in the clubhouse, Phoebus took a businesslike approach on the mound. He made 33 starts, logged 208 innings, winning 14 games and sporting an ERA of 3.33. His only drawback was his wildness, as he issued 114 walks, but his other numbers were good enough for the Sporting News to name him Rookie Pitcher of the Year.

In 1968, Phoebus remained dominant, as the Orioles bounced back to win 91 games during a season that saw the firing of manager Hank Bauer and the hiring of Weaver. It was the Year of the Pitcher, and Phoebus appropriately finished with career highs in a number of categories. He won 15 games, struck out 193 batters, and registered an ERA of 2.62. The height of his season came on April 27, when he faced the Boston Red Sox. Though bothered by a sore throat, Phoebus made his scheduled start, and completely shut down the Red Sox. He allowed only three baserunners – all via walks – in pitching the third no-hitter in the history of the Orioles’ franchise. Aided by two standout plays turned in by Mark Belanger and Brooks Robinson, Phoebus finished off the masterpiece and placed himself in the headlines of newspapers that came out the next day.

Years later, Phoebus recalled the no-hitter with special fondness, given that it took place in Baltimore. “What a great thrill it was to throw a no-hitter in my hometown,” Phoebus told the Baltimore Sun in 2009. “My dream was to play for the Orioles. As kids, we would go to games, sit in the bleachers for 50 cents and ride the right fielder of the opposing team.”

There was little reason for anybody to “ride” Phoebus in 1968, a season that represented the peak of his career. He remained a workhorse in 1969, logging 202 innings, but his ERA rose to 3.52.

The offseason acquisition of Mike Cuellar also affected his place in Baltimore’s starting rotation. During the 1969 postseason, Weaver passed over Phoebus, instead giving starts to Palmer, McNally and Cuellar. Phoebus sat on the sidelines as the O’s took a stunning loss at the hands of the New York Mets in the World Series.

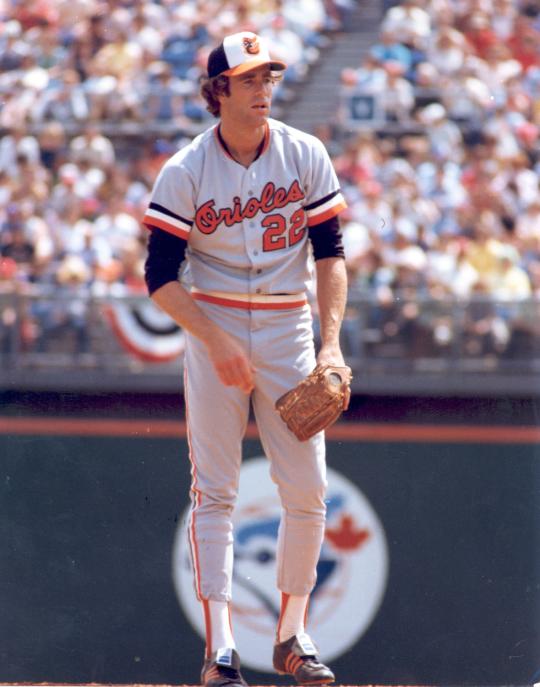

In 1970, Phoebus fell further in the pecking order. Becoming Weaver’s No. 5 starter, Phoebus made only 21 starts, while appearing in six games in relief. His ERA of 3.07 remained impressive, but his strikeout rate fell considerably.

By the postseason, Weaver moved him to the bullpen full time.

In Game 2, Weaver called on him to replace a struggling Cuellar, who was knocked out in the third inning. Phoebus came on to pitch an inning and two thirds of scoreless relief, the Orioles bounced back to take the lead, and Phoebus earned the win in the only postseason appearance of his career. A few days later, the Orioles won the world championship, resulting in a World Series ring for the veteran right-hander.

Unfortunately, Phoebus would not receive his ring in person. That winter, the Orioles made a trade with a recent expansion team, the San Diego Padres. The deal set Phoebus and three other players to the Padres for another right-hander, Pat Dobson.

The trade was not popular with Baltimore fans because of Phoebus’ status as a local boy made good. Yet, it did give him a chance to start regularly in San Diego, rather than continue the role of spot-starting in Baltimore. Still only 29, Phoebus seemed like a natural to become the Padres’ ace. But he endured a terrible start to the season. By July, manager Preston Gomez pulled him from the rotation and demoted him to the bullpen, where he finished out the season.

Phoebus returned to the Padres in the spring of 1972, hoping to reclaim his place in the rotation. He made one start, which turned into a disaster, including six walks. That game became Phoebus’ swan song in San Diego. Only two days later, the Padres sold him to the Chicago Cubs. Leo Durocher used Phoebus almost exclusively in relief. He pitched better, recording an ERA of 3.78, but not well enough to keep his place with the team. That October, the Cubs traded him to the Braves for utility infielder Tony La Russa, the future Hall of Fame manager.

The Braves needed pitching, but Phoebus failed to make the Opening Day roster. He instead spent the entire season at Triple-A Richmond, pitching fairly well, but unable to entice any major league team. At season’s end, even though he was only 31 and still healthy, Phoebus decided to retire.

Forced to make a quick transition to life after baseball, Phoebus he took a job with a company that distributed liquor and then found work with the Tropicana company. But he wanted something more in his post-baseball pursuits and enrolled in college, eventually gaining a degree in education. Upon graduation, he embarked on a long and successful career as a physical education teacher, working at three different elementary schools along the way.

In his later years, Phoebus retired to a life that involved a lot of golf and keeping in touch with his sons.

Phoebus passed away on Sept. 5, the cause of his death unannounced. By all accounts, he seems to have lived a full life, which included his ability to crack that terrific rotation in Baltimore, the achievement of a world championship and a long tenure in teaching.

The guy with a funny name, a man who might have been too short according to some scouts, did pretty well for himself.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame