- Home

- Our Stories

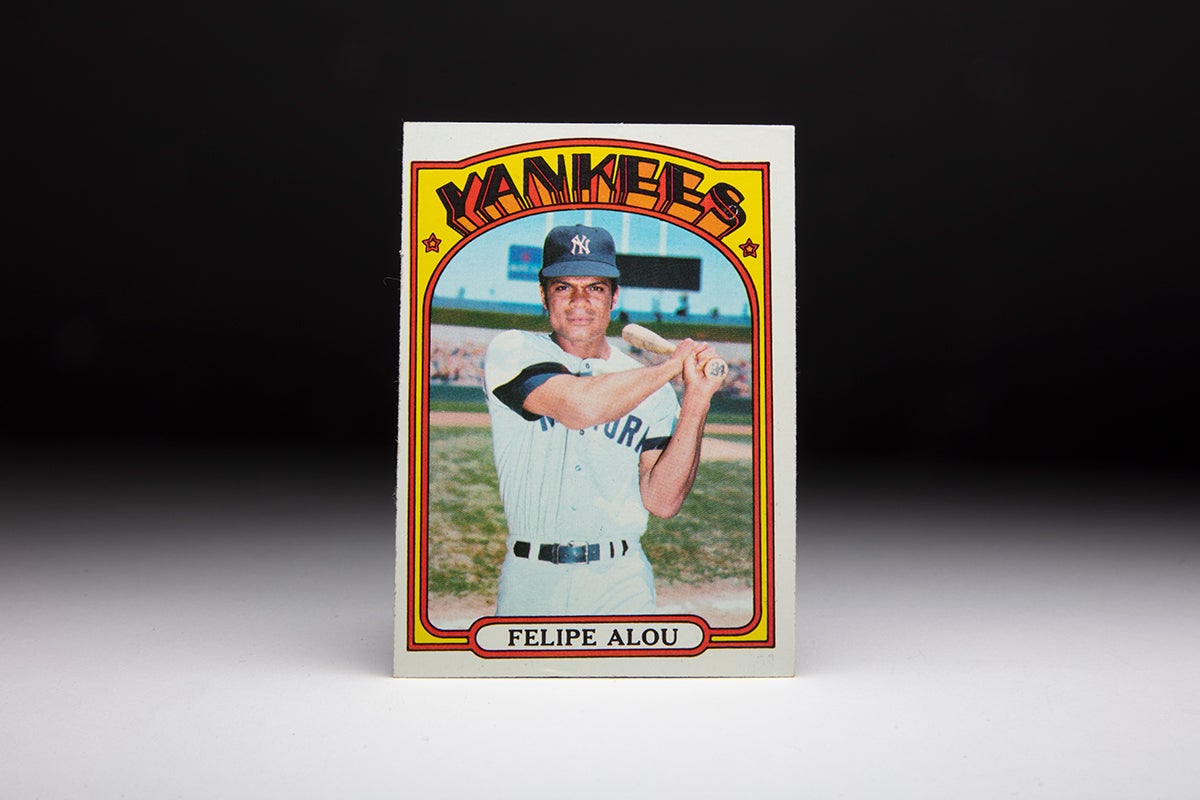

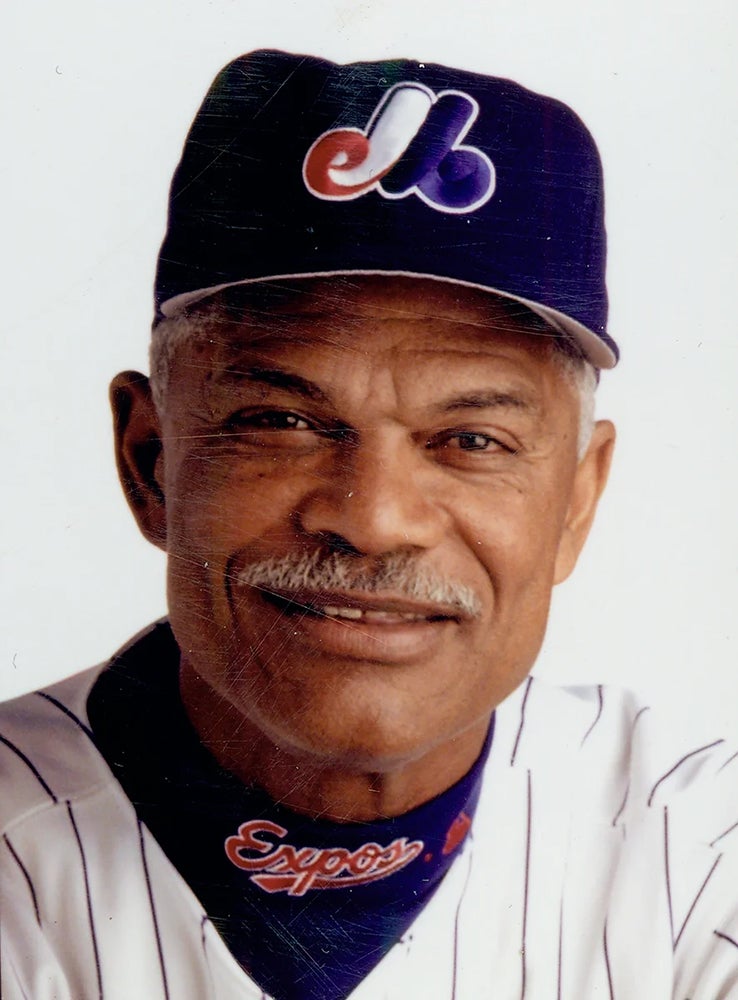

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Felipe Alou

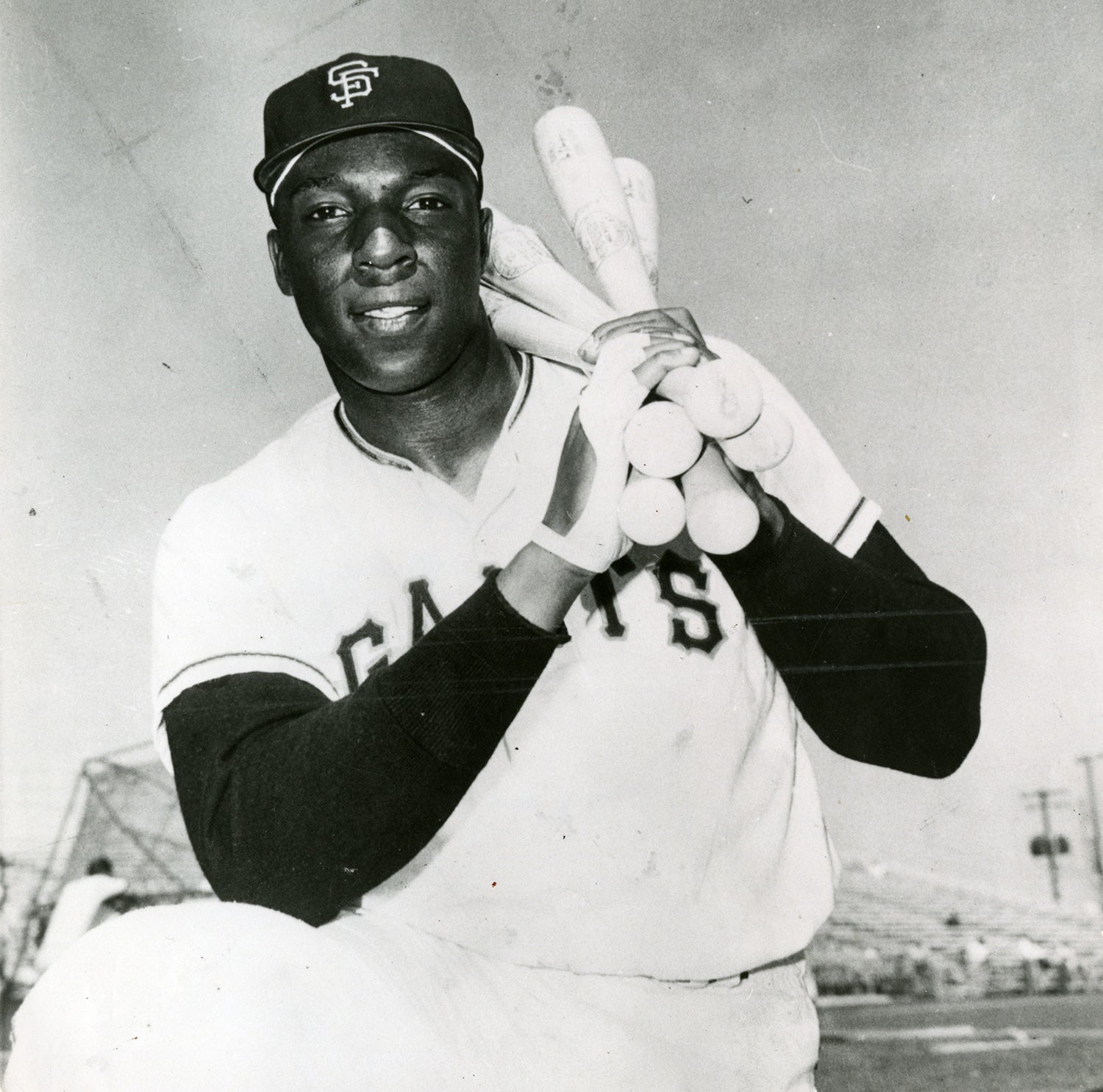

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Felipe Alou

He was the second native of the Dominican Republic to appear in an American or National League game, and Felipe Alou authored a 17-year big league playing career that inspired thousands of his countrymen.

But Alou’s story was only getting started when he retired as an active player. His complete baseball legacy is one that few have ever matched.

Felipe Rojas Alou was born May 12, 1935, in Bajos de Haina, located just west of Santo Domingo along the Caribbean Sea. The first of six children of José Rojas and Virginia Alou, Felipe learned to love the ocean from his father, who was a fisherman and a carpenter.

Alou’s mother was Spanish, and his maternal grandmother came to the Dominican Republic from Spain while fleeing the Spanish Civil War. Known by his paternal name “Rojas” in his home country, Alou was a track star in high school and played baseball for amateur teams. While at the University of Santo Domingo, Alou won a spot on the Pan American Games roster in Mexico City as a sprinter. But while he was there, he was placed on the baseball team and hit cleanup for the squad that eventually won the title.

On Nov. 14, 1955, the New York Giants – following the lead of legendary scout Alex Pompez – signed Alou to a contract.

“Pompez had a scout in the Dominican named Horatio Martínez who was athletic director at the University of Santo Domingo,” Alou told the New York Daily News in 1999. “Martinez had been a great player in the Dominican amateur leagues and he was a god there. He signed all of us for Pompez.”

The Giants sent Alou to Lake Charles of the Class C Evangeline League to start the 1956 season. That’s where he became “Felipe Alou.”

“Before the season started, there was a parade through the town,” Alou told the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel in 1997. “Every player rode in a car with their name on it. I looked at the car I would be riding in, and they put ‘Phil’ – not ‘Felipe’ – ‘Phil Alou.’ I didn’t know any English to dispute that. And by the time I knew enough English to change it, I was able to change my first name back to ‘Felipe.’”

But because the checks he received had the name “Alou” he did not correct the error on the last name. It would be the least of his problems in Lake Charles, La.

About a week before the season, the Baton Rouge (La.) recreation commission – which oversaw the park the Baton Rouge Rebels called home – ruled that Black players could not play in the ballpark. The Lake Charles team featured Alou along with Black players Chuck Weatherspoon and Ralph Crosby, and soon the specter of game forfeits was raised.

On May 6, 1956, the four Black players in the league (two additional Black players were on the Lafayette roster) and Alou were transferred to other minor league teams, with Alou going to Class D Cocoa of the Florida State League.

“I was trying to survive prejudice,” Alou told the Sun Sentinel. “If you are competing against that kind of crap, who cares about a name?”

In fact, while most fans pronounce his name “ah-LOO” the correct Spanish pronunciation is “ah-LOW” in a way that rhymes with “go.”

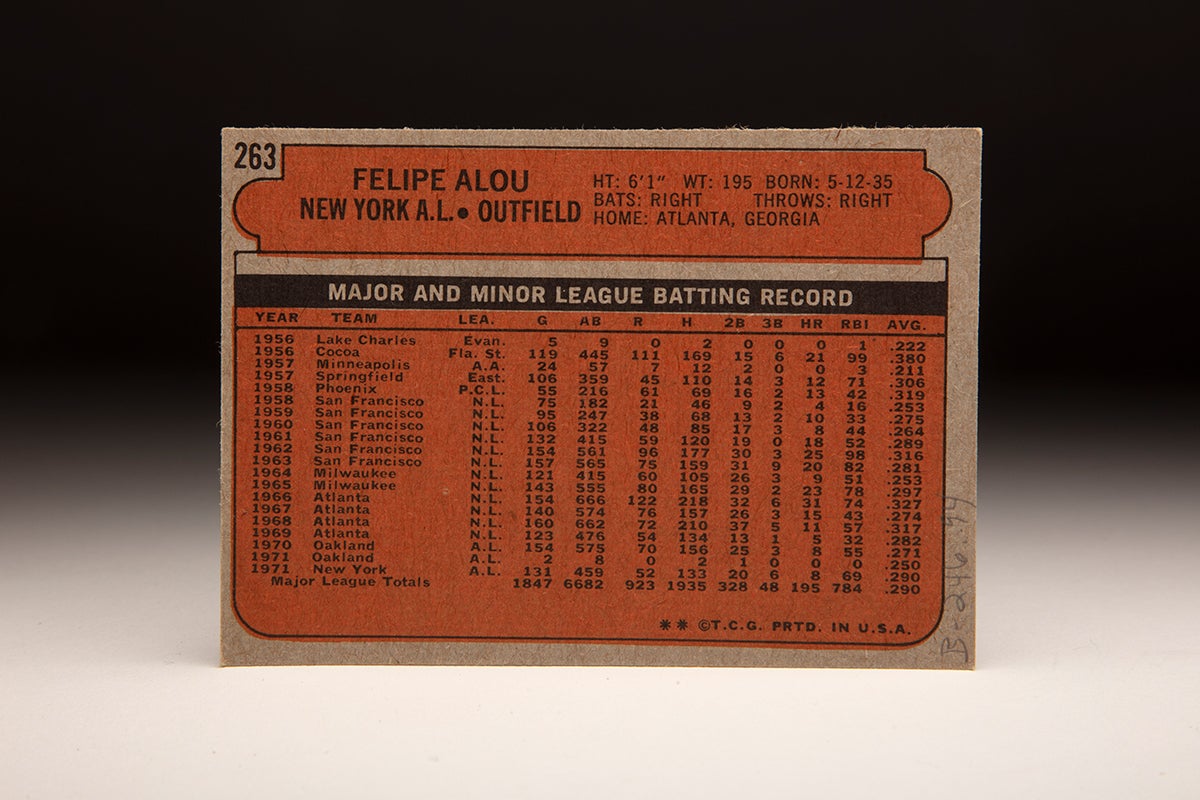

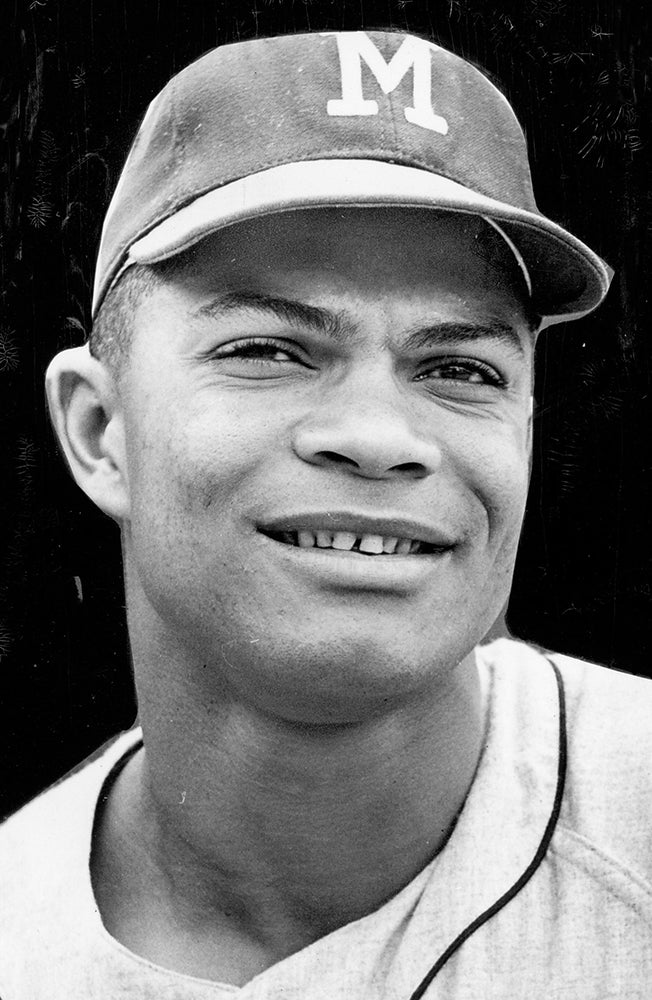

Back on the field, Alou hit .380 with 21 homers, 99 RBI and 48 steals in 119 games with Cocoa, earning a promotion all the way to Triple-A Minneapolis to start the 1957 campaign. He struggled with the Millers before being sent back to Class A Springfield of the Eastern League, where he hit .306 in 106 games.

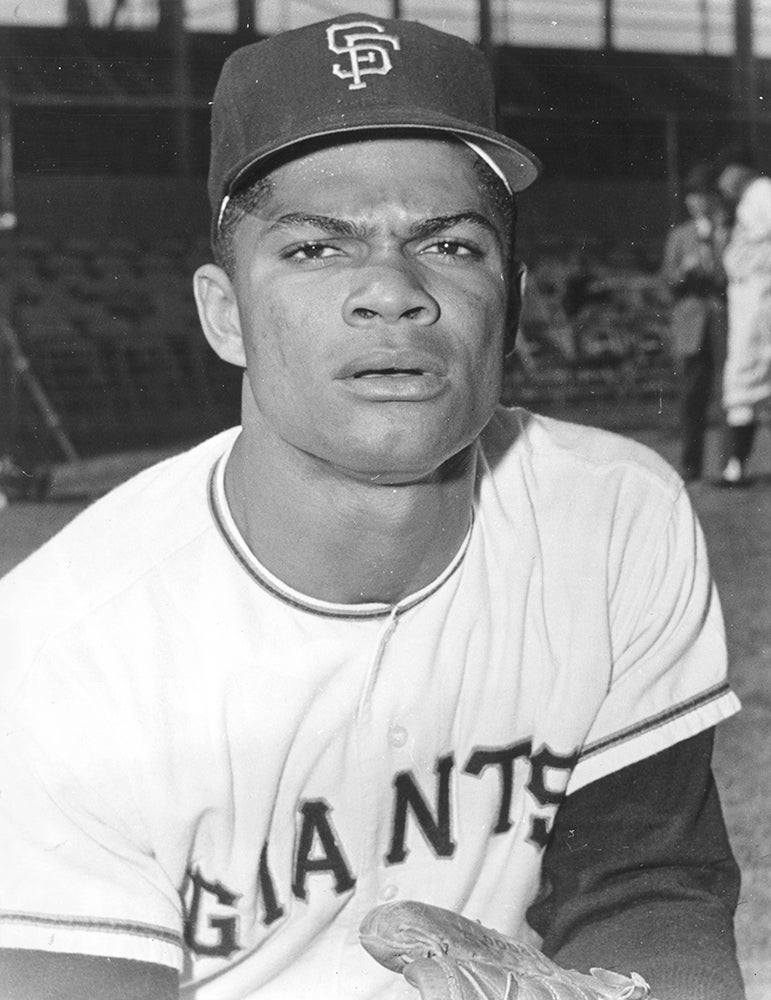

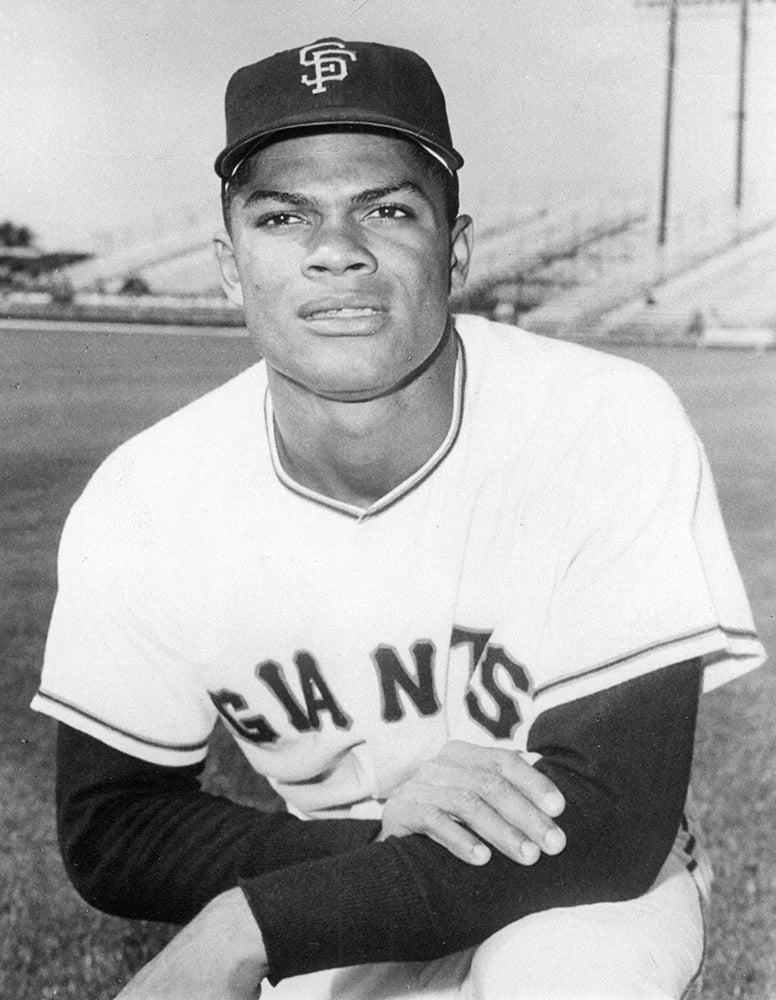

Then in 1958, Alou was hitting .319 with Triple-A Phoenix – the Giants had moved their top minor league club to Arizona after the big league team moved to San Francisco – in June when he was called up to the big leagues. He made his debut on June 8, singling off Cincinnati’s Brooks Lawrence in his first at-bat while playing right field and batting leadoff. Alou appeared in 75 games for the Giants the rest of the year, batting .253 with four homers and 16 RBI while playing all three outfield positions.

The Giants recognized that Alou was ready for regular playing time in the big leagues and kept him on the roster to start the 1959 season. Alou homered in each of his first three games that year and was the team’s starting right fielder through April and into May. But in addition to the legendary Willie Mays, the Giants were flush with young, talented outfielders like Jackie Brandt and Willie Kirkland. And when Willie McCovey made his debut at first base in July, it necessitated the move of Orlando Cepeda – the 1958 NL Rookie of the Year – to left field.

Alou wound up playing in 95 games that year, batting .275 with 10 homers and 33 RBI. He would have a similar role in 1960, hitting .264 with eight home runs and 44 RBI in 106 games.

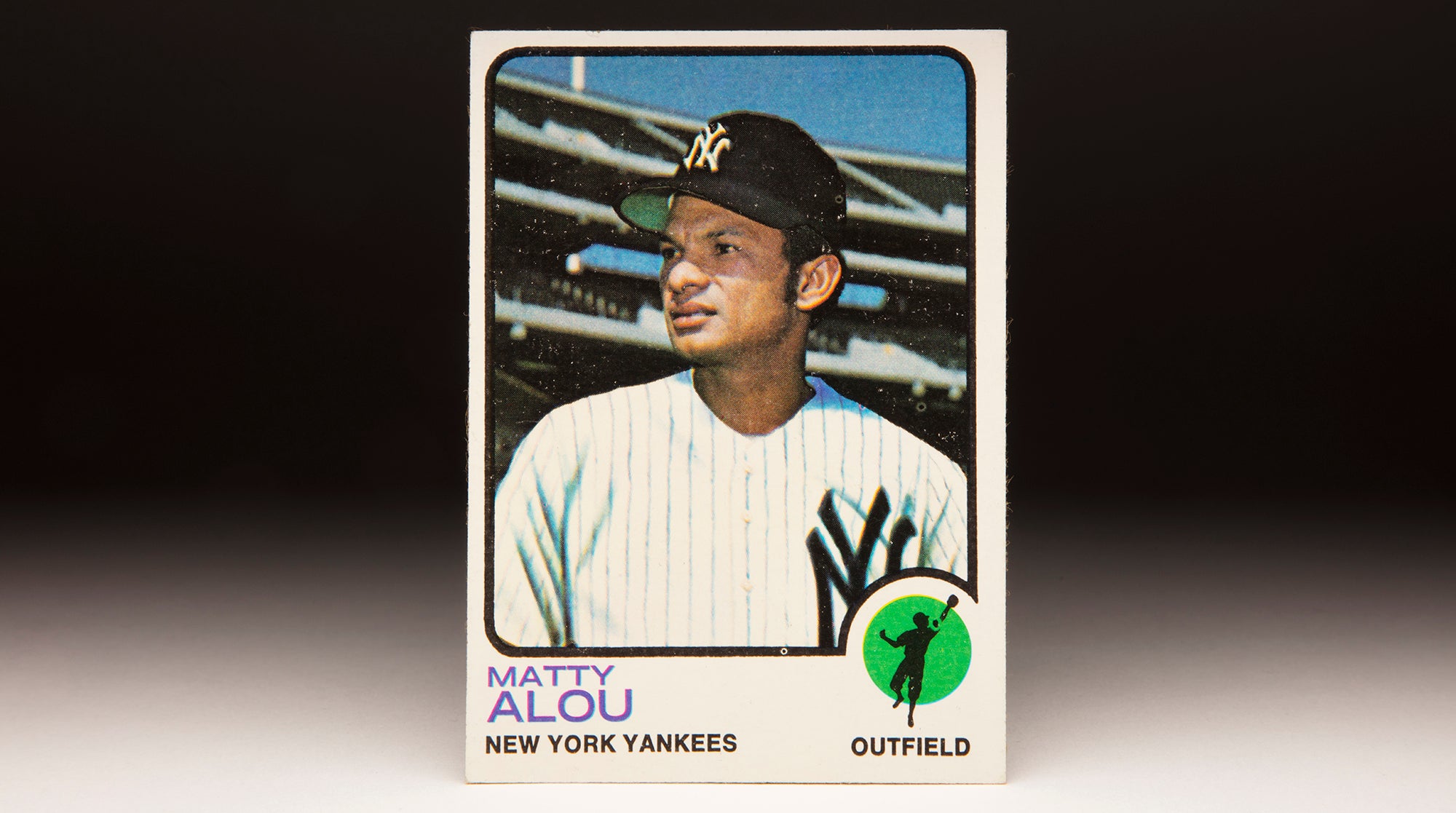

In 1961, Al Dark took over as the Giants’ manager and installed Alou – who had been at his best at the end of the 1960 season – as his Opening Day left fielder. Though he often played right field that year as well, Alou didn’t let the position switches bother him – hitting .289 with 18 home runs and 52 RBI in 132 games. He was joined on the Giants roster by his brother Mateo, who was three-and-a-half years younger and had debuted with San Francisco at the end of the 1960 season.

Matty – as he would be called – went on to play 15 big league seasons. And another brother, Jesús, would debut in 1963 with the Giants. But it was Felipe who would find stardom first among the brothers.

In 1962, Felipe hit .316 with 30 doubles, 25 homers, 98 RBI and 96 runs scored as the Giants finished tied with the Dodgers for the National League pennant. Alou had four hits and two runs scored in the three-game playoff with Los Angeles, scoring the winning run in the decisive third game after drawing an eighth-inning walk off Ed Roebuck. Alou scored on a Jim Davenport walk, giving the Giants – who trailed 4-2 entering the inning – a 5-4 lead in a game they won 6-4 to capture the pennant.

In the World Series against the Yankees, Alou started every game – four in right field at home in San Francisco and three in left field at spacious Yankee Stadium. He had seven hits through the first six games, including two hits and an RBI in a 5-2 Game 6 win for San Francisco that pushed the series to the limit.

In Game 7, the Yankees took a 1-0 lead in the fifth on a double-play ball by Tony Kubek that scored Bill Skowron, and New York maintained that lead into the bottom of the ninth. Matty Alou, pinch-hitting for Billy O’Dell, led off the frame with a bunt single. Felipe was up next, and though he had only two sacrifices on the year, Dark asked him to bunt. But after fouling off the first attempt, Dark took the bunt sign off. Alou wound up striking out on three pitches.

“I tried to bunt and I muffed it,” Alou told the Associated Press. “Then they took the signal off.”

Chuck Hiller followed with another strikeout, but Mays doubled to right field, sending Matty Alou to third. Had he been on second, Alou would have scored easily, but the consensus among observers was that he would have been out at the plate if he had tried to score from first – as Yankees right fielder Roger Maris made a terrific play on the ball.

McCovey then followed with a scorched line drive that was caught by Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson to end the series.

“That’s as hard of a line drive as a guy can hit,” Dark told the AP.

It would be the closest Alou would get to a World Series ring in more than 30 seasons as a player or manager.

In 1963, the Giants could not repeat as NL champions but Alou had another fine season, batting .281 with 20 homers and 82 RBI. He made national news on Sept. 15 when he joined Matty and another brother, Jesús Alou, in the Giants outfield in the eighth inning of a 13-5 Giants win at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh.

The predictions of an all-Alou outfield had surfaced that spring as many scouts considered Jesús the most talented of the three. But it never became a regular occurrence after the Giants traded Felipe to the Braves on Dec. 3, 1963, as part of a deal that brought pitchers Bob Hendley and Bob Shaw to San Francisco.

“I’m very happy,” Braves manager Bobby Bragan told the Independent of Long Beach, Calif., after a deal that took Alou – considered the most marketable bat on the block that offseason – to Milwaukee. “We’ll have a championship outfield with (Hank) Aaron, Alou and (Eddie) Mathews or (Lee) Maye.”

Alou was the Braves’ starting center fielder on Opening Day in 1964 but suffered a knee injury during infield practice in late June after the Braves moved him to first base to allow rookie Rico Carty to enter the lineup. Alou missed about a month and finished the season batting .253 with nine homers and 51 RBI in 121 games.

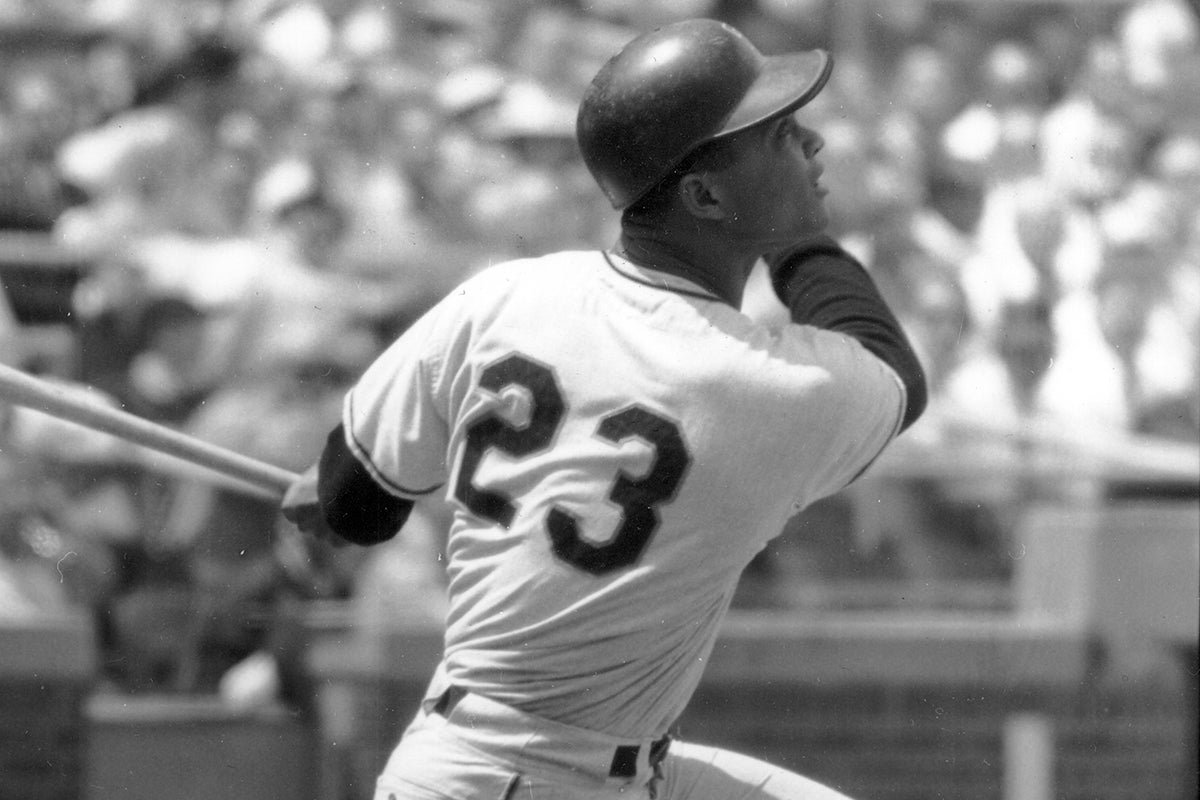

He bounced back in 1965 with a .297 batting average, 23 homers and 78 RBI while splitting his time between first base and left field in the Braves’ final season in Milwaukee. Then in 1966, Alou had what would be his best big league campaign, hitting .327 with 31 homers, 74 RBI and league-leading totals in hits (218), runs (122) and total bases (355) in the franchise’s first season in Atlanta.

Alou was voted the team’s Most Valuable Player and finished fifth in the NL MVP vote while being named to his second All-Star Game.

“I thank God I’ve been so aggressive,” Alou told the San Francisco Examiner, citing a preseason magazine story that criticized him for providing motivation. “I don’t know why it is, or just when it began, but I feel I’m a better ballplayer now.”

Alou split time between first base and the outfield in 1966 and did so again in 1967 when he hit .274 with 15 homers and 43 RBI while batting with bone chips in his right elbow. He had surgery to correct the problem following the season and was moved to center field for 1968, where he starred in the Year of the Pitcher – hitting .317 with 11 homers, 57 RBI and 210 hits – a total that tied for the MLB lead.

Alou was hitting .335 through May of 1969 despite suffering a hairline fracture in his left hand in the middle of the month. He played through that injury but suffered a broken finger on June 2 when he was hit by a pitch by the Cardinals’ Chuck Taylor. The injury sidelined Alou for about two weeks and put a strain on his relationship with the Braves when the team soon traded for outfielder Tony González to fill the void. When Alou returned, his playing time was limited. The Braves wound up winning the inaugural NL West title that year, but by the end of the season, Alou was a bench player and appeared in just one game in the NLCS vs. the Mets as a pinch-hitter. He finished the season with a .282 batting average but with just five homers and 32 RBI.

On Dec. 3, 1969, the Braves traded Alou to the Athletics for pitcher Jim Nash.

“I don’t know what happened with (the Braves),” Oakland manager John McNamara told United Press International in the spring of 1970. “But I’ll tell you this: I’m tickled to death to have a player like Alou. He gives you 100 cents on a dollar, and every day.”

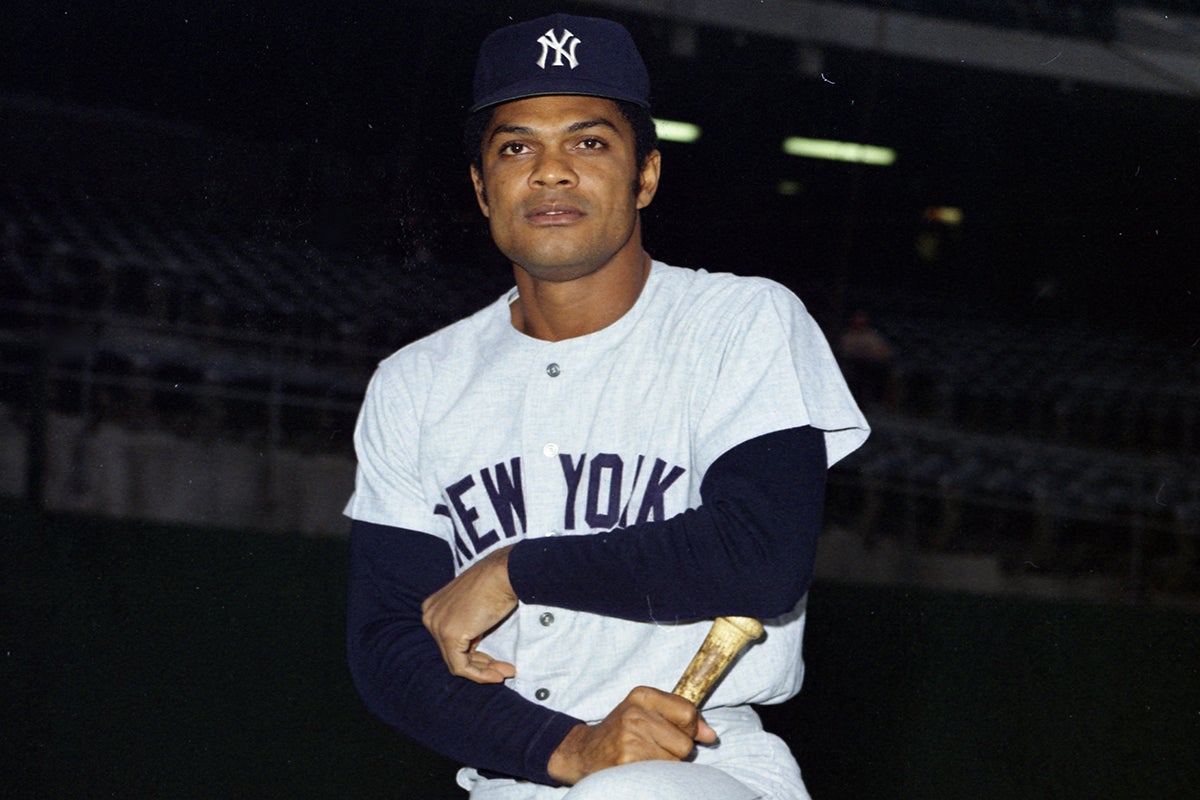

Alou started in left field on Opening Day for the Athletics and played in 154 games, batting .271 with eight homers and 55 RBI. But after just two games in 1971, Oakland sent Alou to the Yankees in exchange for pitchers Rob Gardner and Ron Klimkowski. He provided a steadying veteran presence on a young Yankees team, batting .289 with eight homers and 69 RBI in 131 games. He transitioned into a bench role the following year as he turned 37, batting .278 in 120 games.

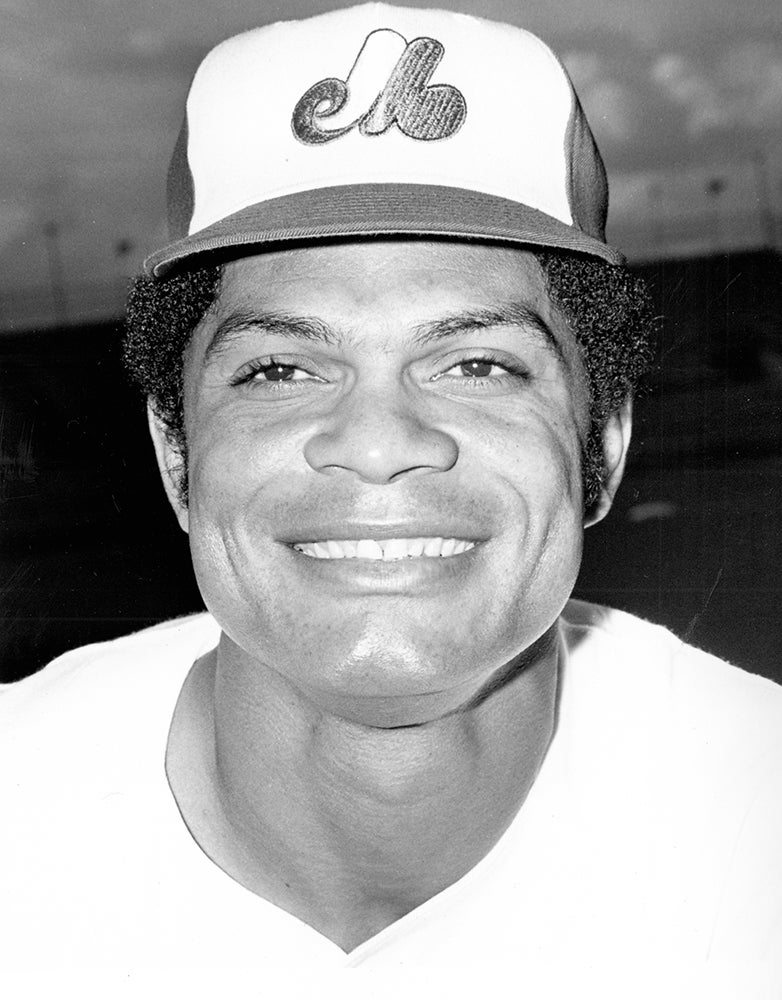

Then in 1973, Alou began to struggle to drive the ball and was hitting .236 with four home runs and 27 RBI in 93 games when the Expos selected him off waivers on Sept. 6. On the same day, the Cardinals claimed Matty Alou – who also spent the 1973 season with the Yankees – on waivers.

“These (deals) are a tribute to the Alou brothers,” Yankees general manager Lee MacPhail told the New York Daily News. “Both have been fine players and it is good that each can be placed where he can help a team in a pennant race. In view of their long service to baseball, we felt they deserved the opportunity of playing for pennant contenders.”

At the time of the transactions, St. Louis was leading the NL East by three games with Montreal tied for second place with Pittsburgh. But the Mets went on to win the division as Felipe batted .208 in 19 games for Montreal.

On Dec. 7, 1973, the Brewers purchased Alou’s contract from the Expos. But in just a few months, Alou had laid the foundation for his next career.

“One of my all-time favorite ballplayers,” Expos manager Gene Mauch told the Montreal Gazette about Alou when the Expos claimed him on waivers.

After appearing in three games as a pinch-hitter without a hit in April of 1974, the Brewers released Alou. He believed he did not get a fair chance at the end of his playing career.

“No Latin player who hits under .240 in the big leagues is forgiven,” Alou told Newsday three weeks after being released. “Although I am still in excellent physical condition, I am not prepared mentally to return to the playing field. The final hour has come for me.”

But the next chapter in his life was about to begin. The Expos brought Alou to Spring Training in 1976 as a special instructor. A week later, Alou left the team and went back to the Dominican Republic after his son, Felipe Jr., passed away in a drowning accident.

He returned to the Expos in 1977 as the manager of Class A West Palm Beach of the Florida State League, leading the team to a division title. He moved up to Double-A Memphis in 1978 before serving on Montreal’s big league coaching staff in 1979 and 1980.

Alou then piloted the Expos’ Triple-A teams for three seasons, returned to the big leagues with Montreal in 1984 and then went back to Triple-A as Indianapolis’ manager in 1985. Six more seasons with Class A West Palm Beach followed as Alou nurtured some of the brightest young talent in the game like Randy Johnson and Larry Walker and his nephew, pitcher Mel Rojas.

In those six seasons, West Palm Beach never had a losing season.

Then in 1992, Alou began the season as the Expos bench coach under Tom Runnells. On May 21, with the Expos at 17-20, the team fired Runnells and replaced him with Alou.

“It took me a while to accept the job, because of (Runnells),” Alou told the Canadian Press. “I was working hard to have things go Tommy’s way and I thought: ‘Here I am taking this man’s job.’

“Then (Expos general manager Dan Duquette) said: ‘I’m making a change regardless.’ And I told him I would accept.”

Alou became the first Dominican Republic native to manage an AL or NL team – a status he nearly achieved in 1985 when the Giants offered him their job.

“It was just a one-year contract,” Alou told the Canadian Press. “You hate to be hired to be fired. I could see it working out that way.”

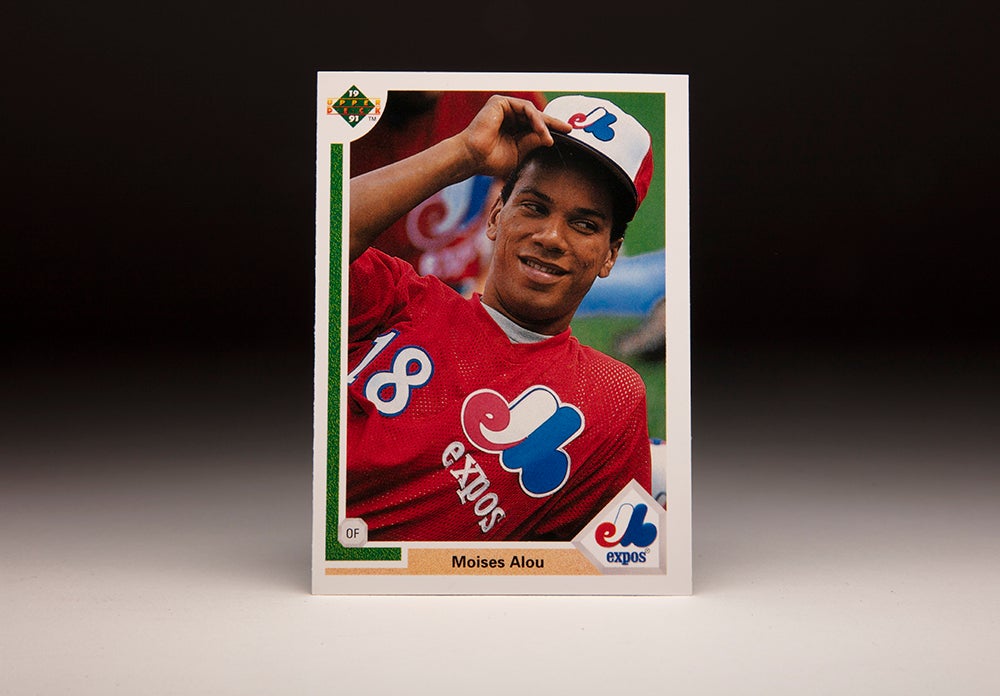

But the Expos presented a different situation. Having managed in the minors for years, Alou knew the team was brimming with future stars – including his son, Moisés Alou. He guided Montreal to a 70-55 record the rest of the season, finishing second in the NL Manager of the Year voting behind Pittsburgh’s Jim Leyland.

Alou led the Expos to 94 wins and a second-place finish in the division in 1993. Then in 1994, Montreal was 74-40 and in first place when the strike ended the season in August. When baseball resumed, the Expos dismantled the team in the face of rising costs – a move that many believed led to the eventual relocation of the franchise.

Alou remained the team’s manager into the 2001 season before being dismissed, winning a franchise-record 691 games. He won the NL Manager of the Year Award in 1994 after finishing third in 1993 and later placing second in 1996.

“I tried my best to help,” Alou said after being dismissed amid rumors that the Expos’ franchise was in peril. “But I believe all those who have tried to fight to keep the club here, most of the time we ran into a wall.”

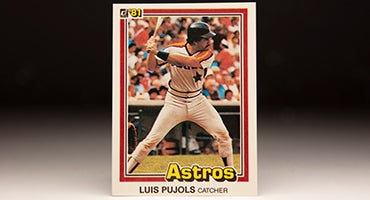

Alou was not out of work for long. He joined the Tigers as their bench coach early in the 2002 season when Luis Pujols replaced Phil Garner as the team’s manager. Then after Dusty Baker left the Giants following the 2002 season, Alou took over in San Francisco. He led a veteran Giants team to 100 wins and the NL West title before the Marlins upset San Francisco in the NLDS. He managed the Giants for three more seasons, remaining with the franchise as an advisor even after he was dismissed from his job as manager.

Overall, Alou managed 14 big league seasons, going 1,033-1,021. His full-season teams finished third-or-better eight times, and he garnered votes in the Manager of the Year balloting in seven seasons.

As a player, Alou hit .286 with 2,101 hits, 359 doubles and 206 home runs in 17 seasons. He is one of only 10 players in AL/NL history with at least 2,000 hits who also won at least 1,000 games as a manager.

Few ever contributed as much to the game of baseball.

“I think I did well because I’ve always been somebody who, even in the Deep South with all those differences and problems and races, I always kept my dignity in spite of anybody and in front of anybody,” Alou told the Associated Press in 2003. “I kept my belief that I was a human being as good as anybody.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum