- Home

- Our Stories

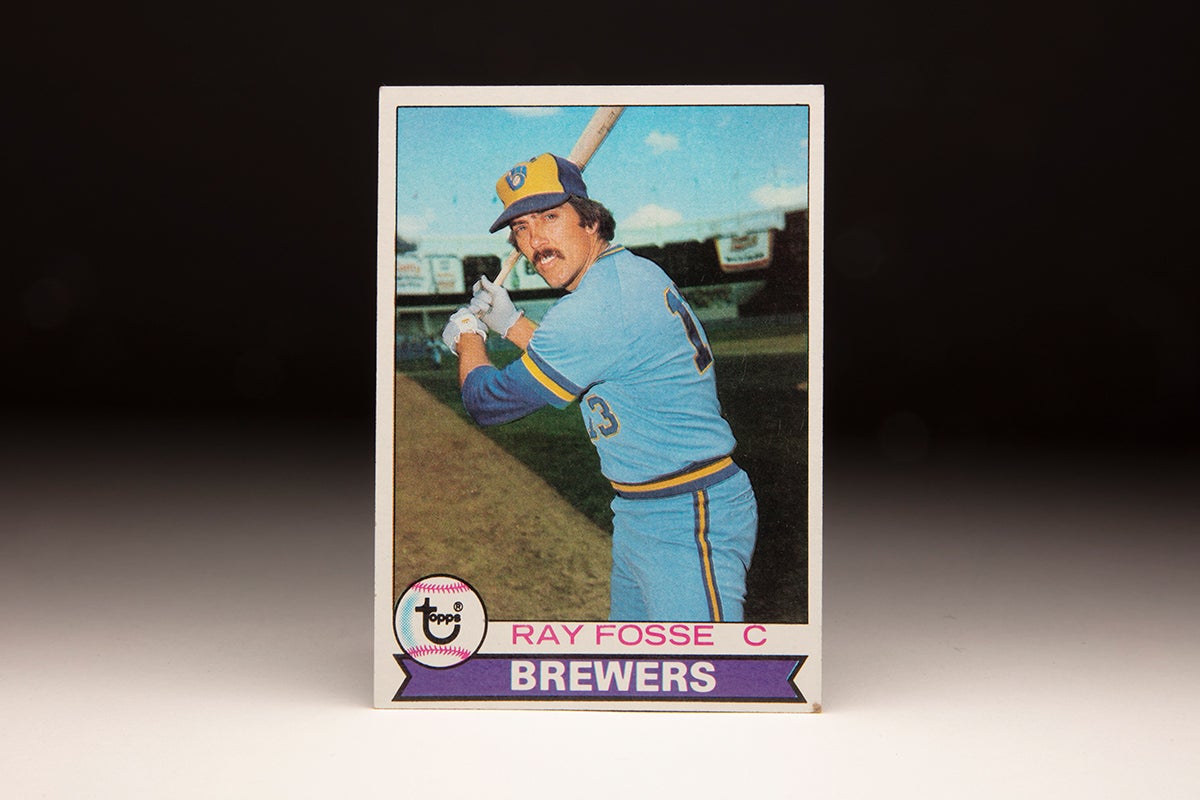

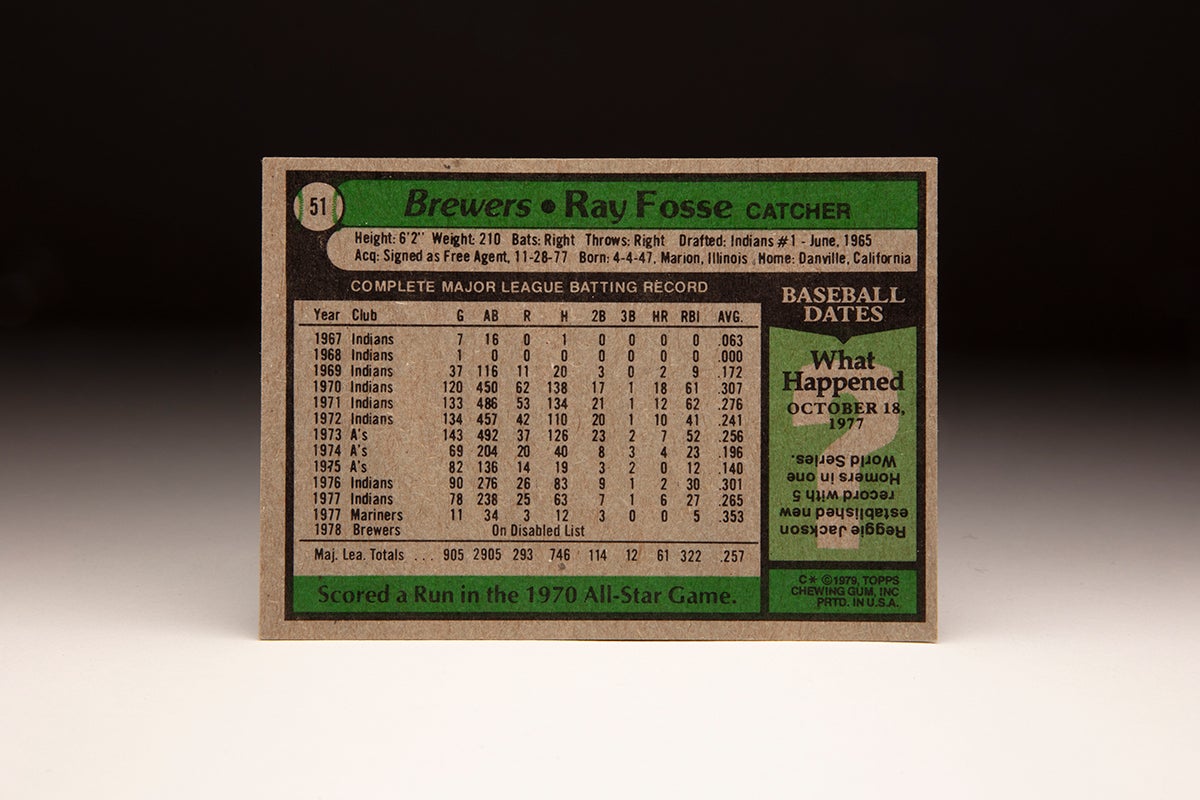

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Ray Fosse

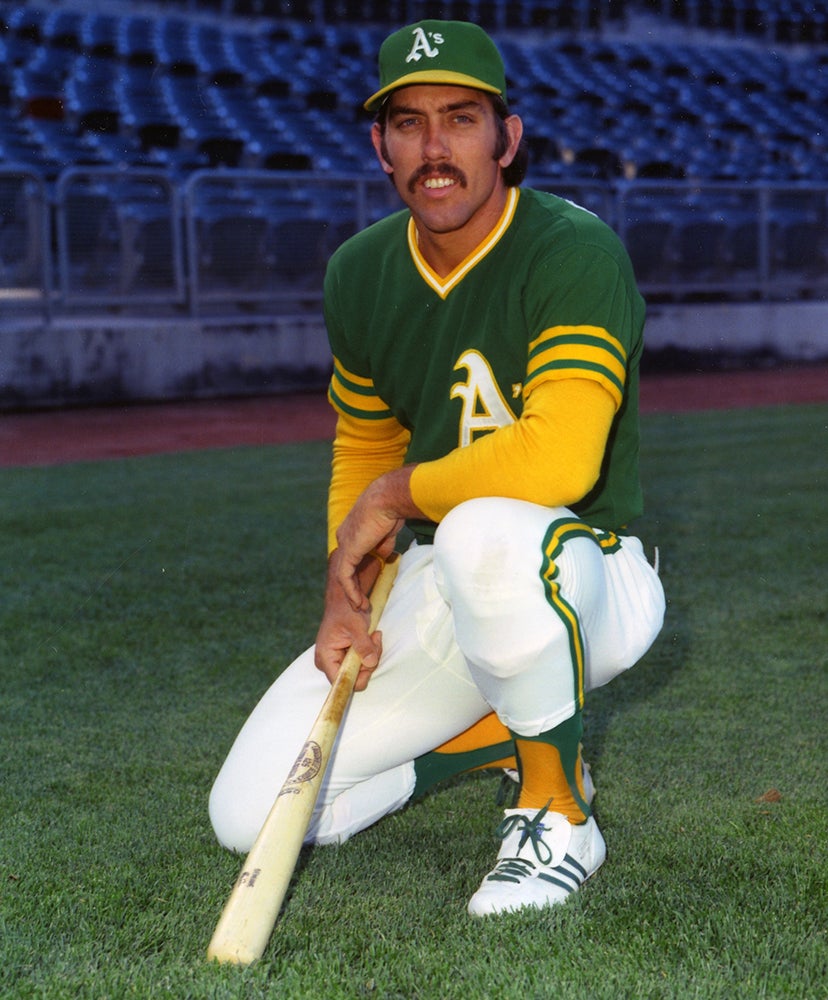

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Ray Fosse

The myth grew steadily throughout the 1970s, gaining traction within months after the first All-Star Game of that decade.

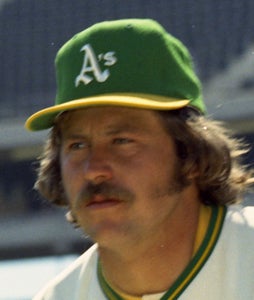

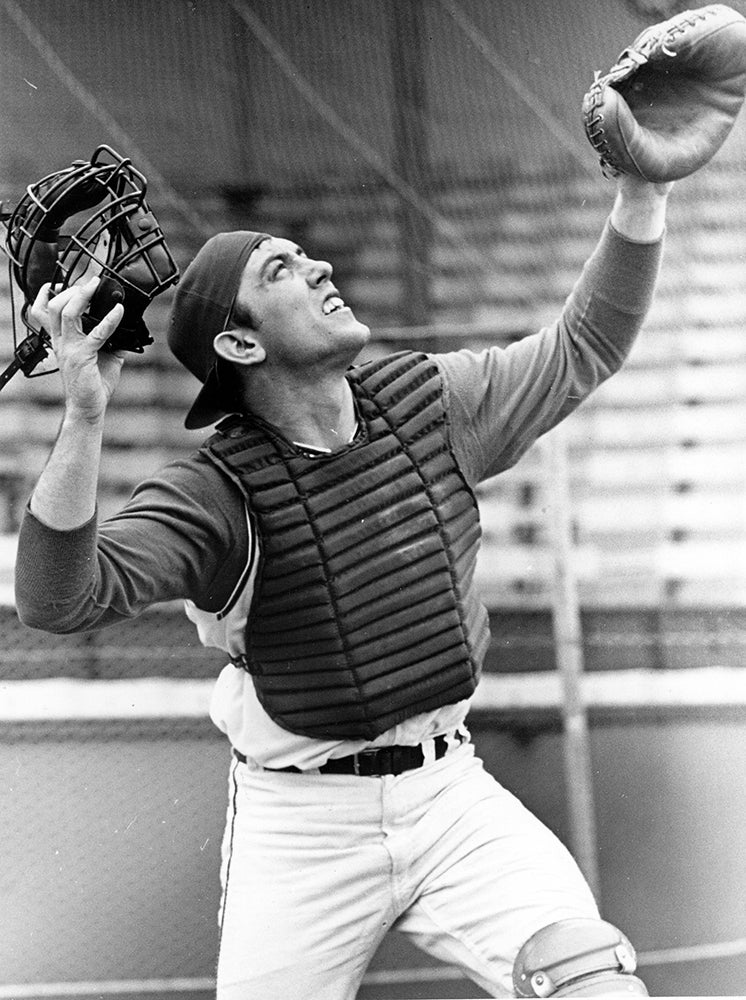

As the story goes, Ray Fosse was never the same after Pete Rose bowled him over at home plate to score the game-winning run on July 14, 1970, at the Midsummer Classic at Riverfront Stadium. Lost in that narrative, however, was that Fosse was an All-Star and Gold Glove Award winner again in 1971, was the primary catcher on Oakland’s World Series winners in 1973 and 1974 and hit .301 for Cleveland in 1976.

Over 12 big league seasons, Fosse was more than just an All-Star Game footnote. He was one of the game’s best catchers.

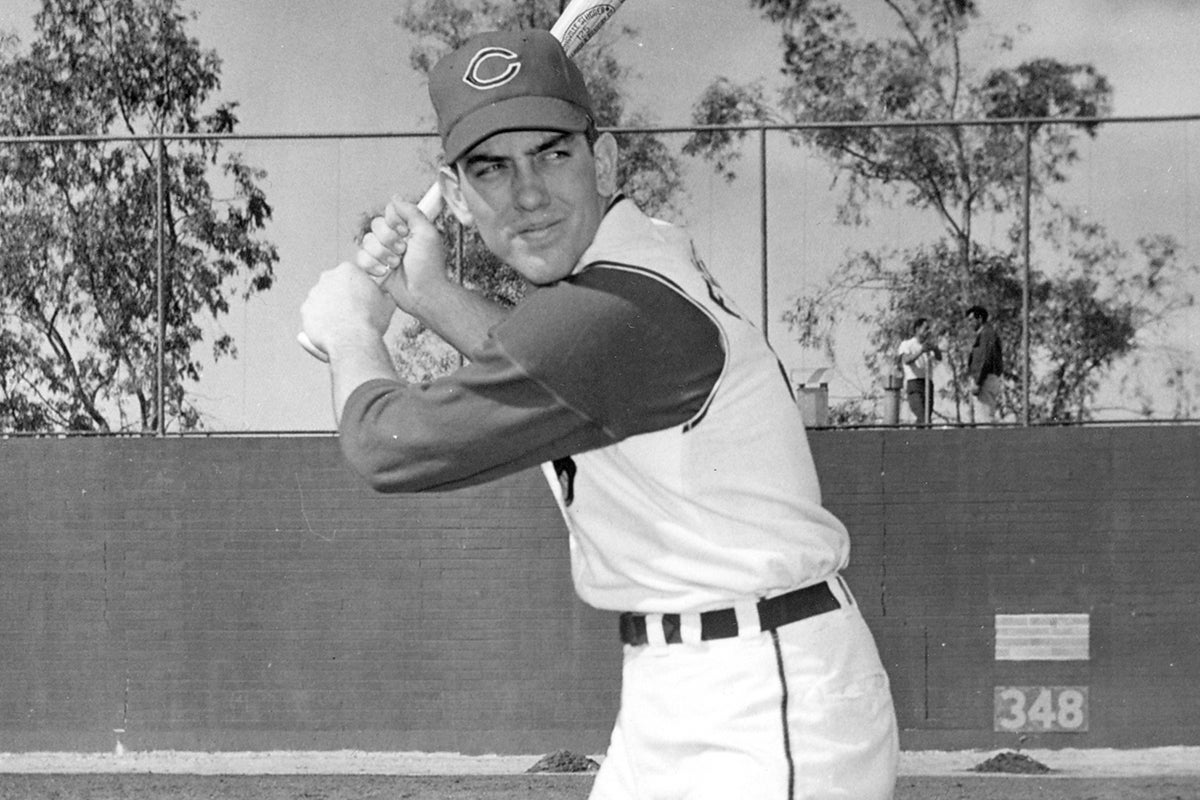

Raymond Earl Fosse was born April 4, 1947, in Marion, Ill. – about an hour north of the Kentucky state line – and starred in football, basketball and baseball for Marion High School. When he suffered a broken left collarbone in an American Legion baseball game on June 10, 1964, the news made headlines in the local paper.

Fosse graduated high school in 1965 and was taken with the No. 7 overall pick by Cleveland in the inaugural MLB Draft. Media reports indicated his signing bonus was worth $50,000.

The Indians sent Fosse right to Double-A Reading of the Eastern League, where he hit .219 in 55 games against opponents that were an average of five years older than he was. Fosse was sent to Class A Reno in 1966, and his average improved to .304 with 54 RBI in 116 games. Then in 1967, the Indians promoted Fosse to Triple-A Portland, where he batted .261 in 75 games – missing the first part of the season while attending Southern Illinois University – before earning a September call-up to Cleveland.

He debuted for the Indians on Sept. 8 and finished the month with one hit in 16 at-bats over seven games.

“Fosse is highly regarded after just three seasons in organized baseball,” Russell Schneider, who covered the Indians for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, wrote in a late-season piece that appeared in the Sporting News. “He’s 20 and batted .261 at Portland – but more impressive was his work behind the plate, where the Indians have been dissatisfied with Joe Azcue and Duke Sims.”

Fosse spent almost the entire 1968 season with Portland, hitting .301 in 103 games before catching two innings against the Twins on Sept. 11 in his only big league contest of the season. Rumors had him on the trading block throughout the offseason as the Indians pondered their crowded roster of catchers, but Fosse stayed put and made the Opening Day roster in 1969 after Sims broke his fingers in Spring Training.

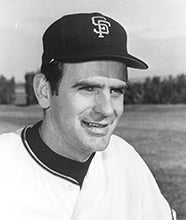

“He looks like he’s about ready,” Cleveland manager Al Dark told the Evansville Courier and Press.

Azcue started the first three games of the season before Fosse started Game 4 on April 12. The Indians then traded Azcue to the Red Sox on April 19 in a six-player swap that brought Ken Harrelson to Cleveland, opening the door for more playing time for Fosse. But after starting for much of May and the first week of June, Fosse was sidelined when a foul ball broke his right index finger in a game against the White Sox on June 10. He didn’t return to the lineup until September, finishing the season with a .172 batting average in 37 games.

But 1970 proved to be Fosse’s breakout season. He started on Opening Day for the Indians and was hitting .333 on May 1 before a slump dropped his average about 80 points. But he singled in the ninth inning against Mudcat Grant of the Athletics on June 9, starting a 23-game hitting streak that would push his batting average back over .300. He was named to the American League All-Star Game as a reserve, entering the break with a .312 average.

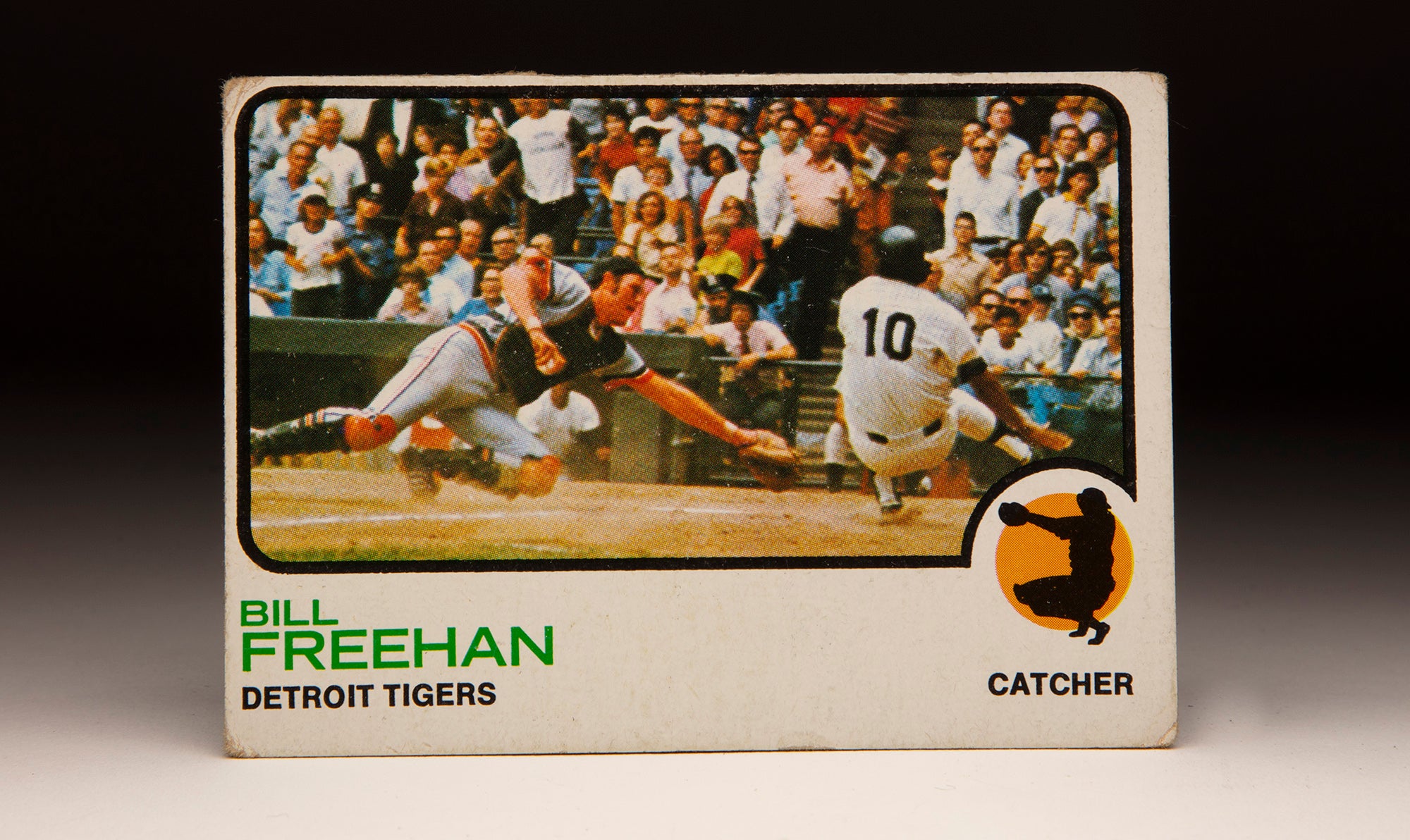

Fosse entered the All-Star Game in the bottom of the fifth inning in relief of starter Bill Freehan. Fosse singled to lead off the sixth inning and later scored on a Carl Yastrzemski single, giving the American League a 1-0 lead. Fosse then extended the AL advantage to 2-0 in the seventh inning with a sacrifice fly that scored Brooks Robinson. Fosse drew a walk off Bob Gibson in his third plate appearance in the ninth but was stranded at first base. But the AL could not hold its 4-1 lead in the bottom of the ninth as Roberto Clemente’s sacrifice fly scored Joe Morgan to tie the game.

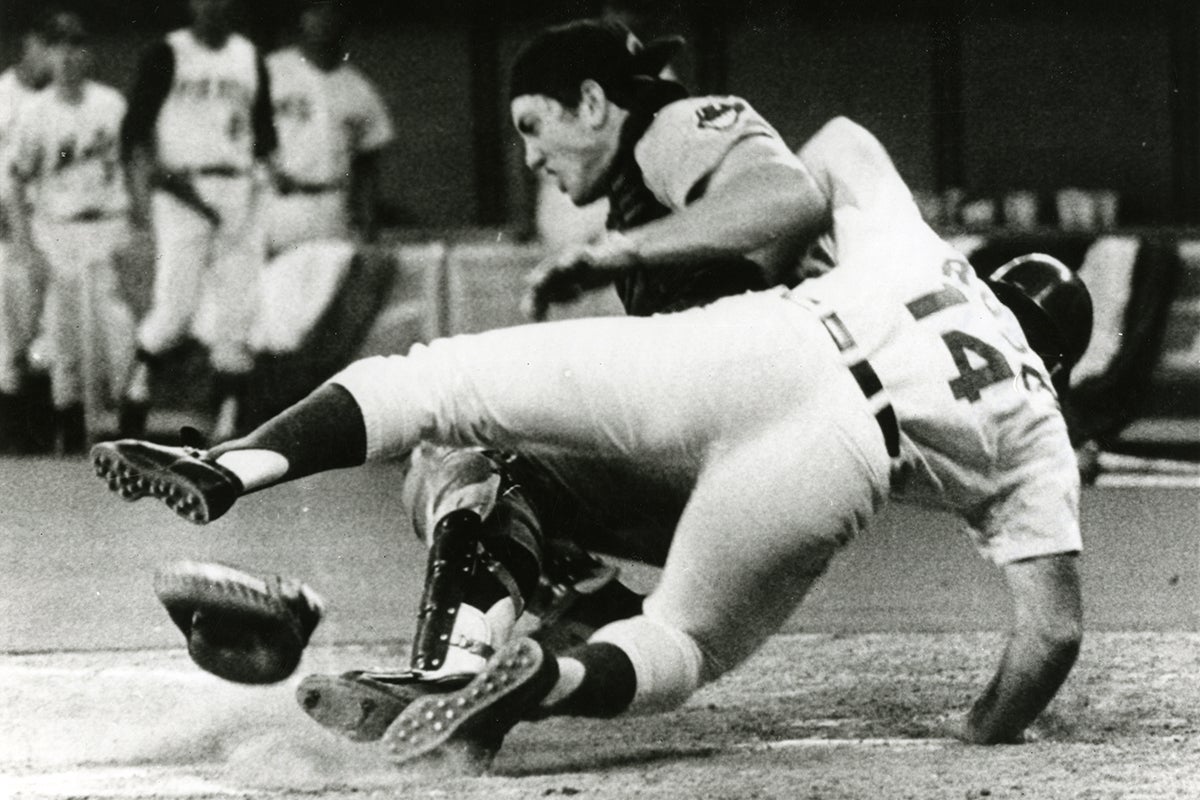

Fosse grounded out in the 11th inning, and in the bottom of the 12th history came calling.

After Clyde Wright of the Angels got Joe Torre and Clemente to each ground out to start the frame, Rose singled to center. Billy Grabarkewitz followed with a single to left to put Rose on second, and Jim Hickman then singled to center. The throw from Amos Otis arrived just as Rose did, and Rose threw his left shoulder into Fosse’s left side, knocking the mitt from Fosse’s hand and smashing Fosse to the ground.

Rose then defiantly stepped on the plate with the winning run.

“You’ve got to score it any way you can,” Fosse told the Jersey Journal after the game as trainers feared he might have broken his shoulder. “I didn’t catch the ball. I was getting ready to catch it when he hit me.

“Some of the guys thought he could have stepped around me or slid under me. I don’t really know. I was too busy trying to catch the ball.”

Cubs manager Leo Durocher, who was the third base coach for the NL, defended Rose’s decision to run over Fosse.

“I was only five or 10 feet away,” Durocher, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1994, told the Associated Press. “There was no other way (Rose) could have reached the plate except the way he did. If he dives, he’d have broken his neck or collarbone. If he slides, he doesn’t get past Fosse’s block. So Pete did the only thing he could do. That’s the only way Pete Rose was taught to play.”

Fosse escaped without any broken bones but was severely bruised. Two days later, however, he was back in the starting lineup for Cleveland and played in 10 games in nine days coming out of the All-Star break, including catching both games of a doubleheader against the Royals on July 24. For many of those games, Fosse said he couldn’t lift his left arm above his head.

The player known as the Marion Mule was aptly named.

“Ray is a fighter. To Ray, that plate is his kingdom,” Cleveland teammate Sam McDowell told United Press International after the All-Star Game. “If there’s gonna be a play that’s going to mean the ballgame, Ray isn’t going to budge.

“Look, he’s built like a rock. If Ray makes up his mind to block the plate, nobody is gonna get by him.”

Fosse played almost every game throughout July and August before suffering a broken right index finger on Sept. 3 against the Senators on a foul ball that ended his season. He finished the year hitting .307 with 18 home runs, 61 RBI and 62 runs scored. Defensively, he led the AL in putouts (854) and caught stealings (48) and finished second with a caught stealing percentage of 54.5.

Fosse earned his first Gold Glove Award during the offseason and finished 23rd in the AL Most Valuable Player voting.

Fosse had another outstanding season in 1971, batting .276 with 12 homers, 62 RBI and 21 doubles. He was again named to the All-Star Game – although he did not appear in the game due to a left hand injury sustained during a melee with the Tigers – and won another Gold Glove Award while leading all AL catchers with 16 double plays.

“Last year wasn’t a great year for me, although I think I was hitting just as well as ever the last month or two of the season,” Fosse told the AP in Spring Training in 1972. “I was hurt before that and couldn’t get going.”

Fosse appeared in 134 games in 1972 but saw his average drop to .241 with 10 homers and 41 RBI. But he helped teammate Gaylord Perry win the AL Cy Young Award that year as Perry went 24-16 with one save and a 1.92 ERA over 342.2 innings. Perry had a decision or a save in each of the 41 games he pitched.

“Fosse pushes you for nine innings, sets up your pitches and is the best thing that could happen to a pitcher in tight situations,” Perry told UPI. “(He is) one of the big reasons for my winning the Cy Young Award.”

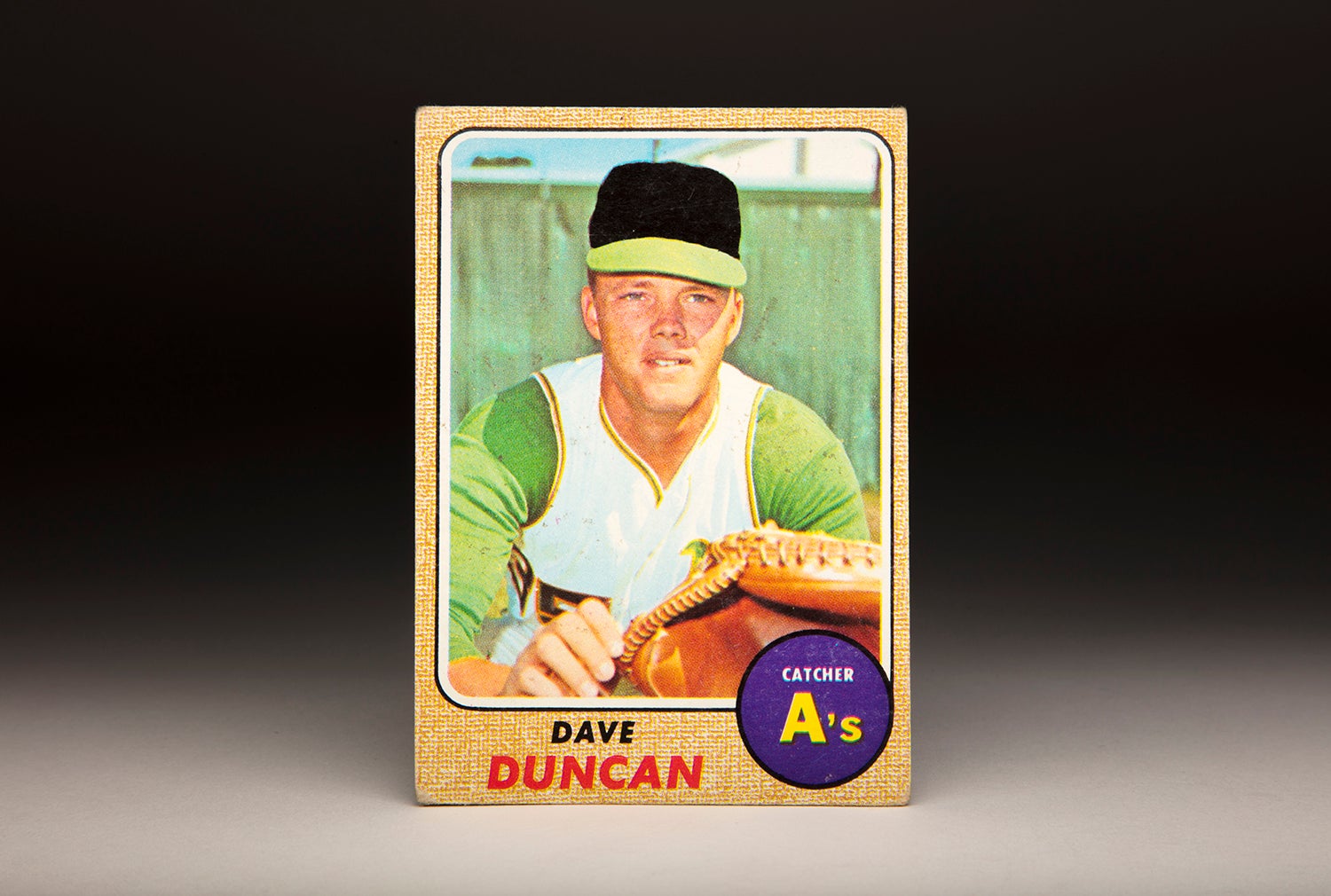

But when the Athletics made talented outfielder George Hendrick available in the spring of 1973, the Indians decided they could afford to part with Fosse. On March 24, Cleveland sent Fosse and infielder Jack Heidemann to Oakland for Hendrick and catcher Dave Duncan.

Suddenly, Fosse found himself with the defending world champions.

“Sure, we had to give up a great guy – and Fosse is one of the finest guys I know,” Cleveland manager Ken Aspromonte told the Plain Dealer after a trade that shocked most players in the Indians clubhouse. “But you’ve got to give up something good to get something good.”

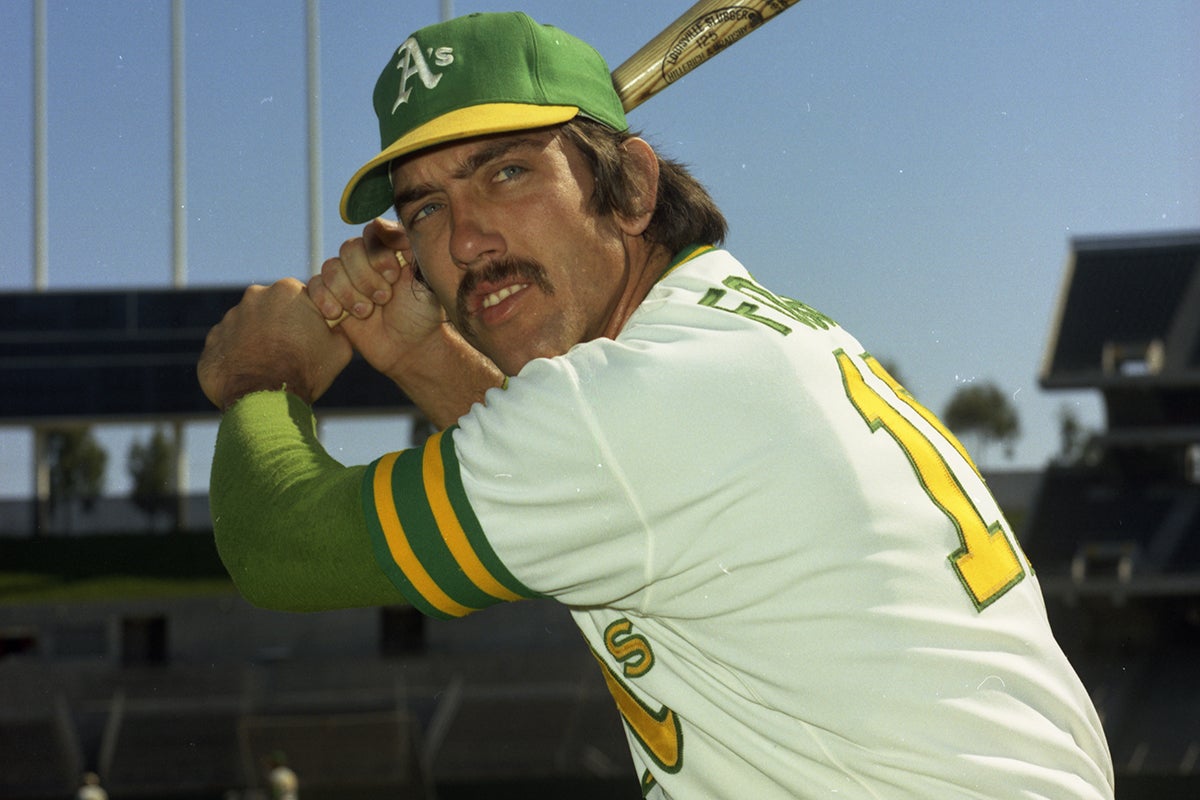

Fosse fit in immediately with Oakland, appearing in 143 games while catching a staff that featured three 20-game winners in Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue and Ken Holtzman. Fosse hit .256 with seven homers and 52 RBI but he struggled in his first taste of postseason action, going 1-for-11 (.091) in the Athletics’ five-game win over Baltimore in the ALCS and then 2-for-18 (.111) in the first five games of the World Series against the Mets.

Fosse started all 10 of those contests, but in the final two games of the Fall Classic, Oakland manager Dick Williams went with bat-first catcher Gene Tenace as the starter. Fosse entered each of those two games as a late defensive replacement, and Oakland won both of them to claim the World Series title.

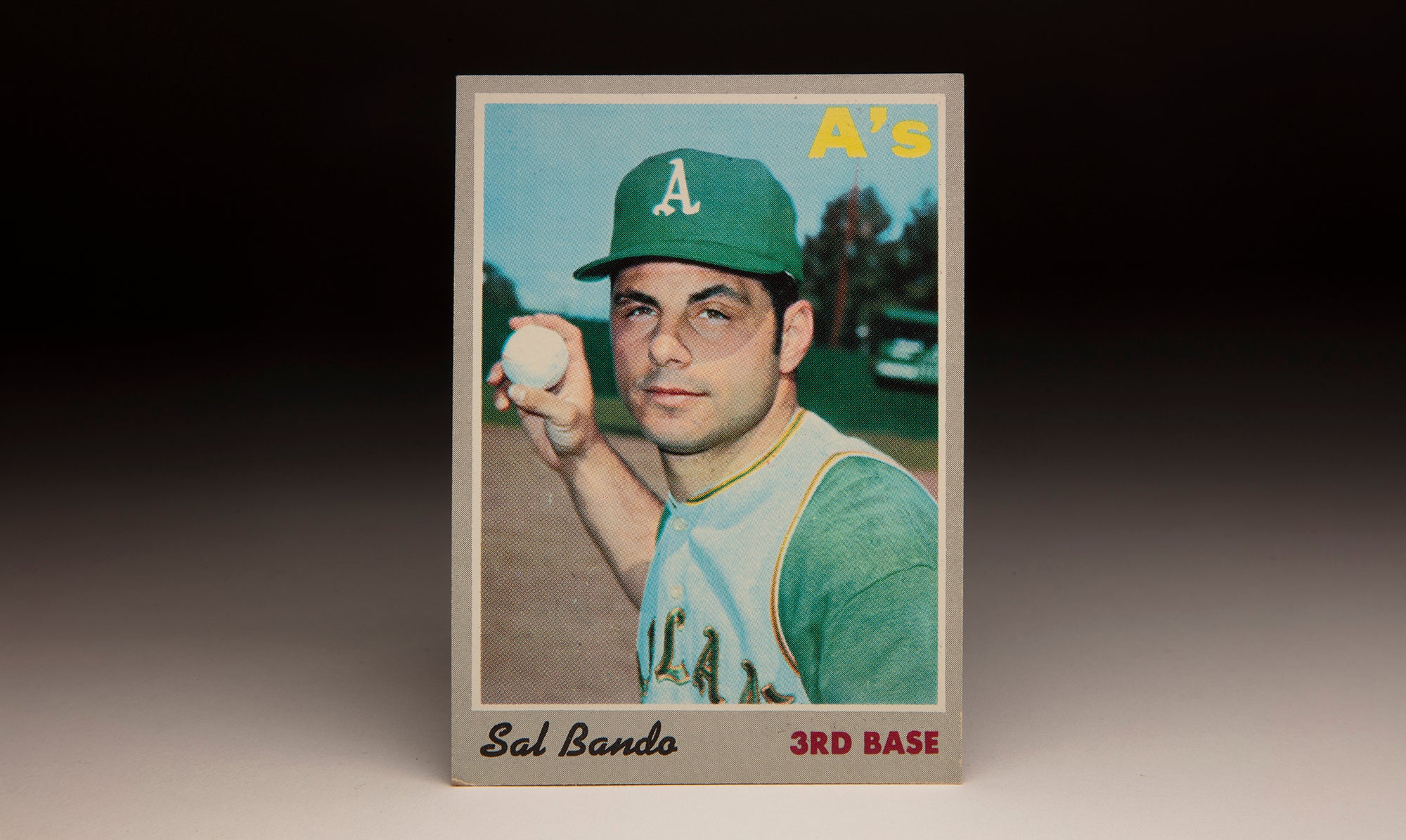

After New York’s Wayne Garrett popped out to shortstop to end Game 7, Fosse embraced third baseman Sal Bando and pitcher Darold Knowles on the mound – a moment captured in a photo that ran in newspapers around the country.

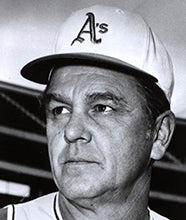

Fosse reconnected with his manager in Cleveland, Al Dark, when Williams resigned as skipper immediately after the World Series and Athletics owner Charlie Finley brought back Dark for a second stint as his manager – Dark having led the A’s in Kansas City in 1966 and 1967. Fosse was hitting .203 through June 5 when he injured his shoulder and back while trying to break up a clubhouse fight that night between teammates Reggie Jackson and Bill North. Fosse spent the next 11 weeks on the disabled list before returning in late August, reclaiming his starting catching role.

Fosse hit .196 with four homers and 23 RBI in 1974 but once again helped the A’s advance to the World Series, where his peculiar flip of the ball back to the pitcher – a flat-footed lob – drew national attention. The throw stemmed from a case of the “yips” that started with an errant throw to pitcher Luis Tiant during Spring Training in 1966.

“The only time I could really unload a throw was when a guy was stealing and I didn’t have time to think about my release,” Fosse told the Plain Dealer. “But if no one was on base, or if a guy was on base but wasn’t running, there were times when I just couldn’t throw the ball.

“For a while, I was afraid I’d have to quit or at least quit catching. But this season, some of the pitchers here suggested that I try not to make my throws back to them so perfect and without that hard snap. So that’s what happened. I just started lobbing the ball and I guess everybody likes it better, even if it doesn’t look as good.”

Fosse hit better in his second year of postseason play in 1974, batting .333 in the ALCS vs. Baltimore and then .143 in the World Series against the Dodgers as the Athletics won their third straight title. Fosse’s home run in the second inning of Game 5 gave Oakland a 2-0 lead in a game the A’s won 3-2 to clinch the crown.

In 1975, however, Dark and the A’s decided that Tenace would be their everyday catcher, relegating Fosse to a backup role. He hit .140 over 82 games as Oakland won its fifth straight AL West title. But the A’s were swept by Boston in the ALCS, with Fosse appearing only in Game 2. It would be the last postseason contest of his career.

On Dec. 9, 1975, the Athletics sold Fosse’s contract to the Indians.

“My situation in Oakland wasn’t very good,” Fosse told the Arizona Daily Star in Spring Training of 1976. “I hadn’t done too much the last two years.

“I’m very happy (with the Indians). It’s like coming home.”

Fosse split time with Alan Ashby behind the plate in 1976 and hit .301 in 90 games. The Indians traded Ashby to the Blue Jays following the season, and Fosse was the Opening Day catcher in 1977. He was hitting .265 through 78 games when Cleveland traded him to Seattle on Sept. 9 in exchange for pitcher Bill Laxton and $20,000.

With Fosse eligible for free agency following the 1977 season, many expected the trade – especially since the Indians decided in August that Fred Kendall would be the starting catcher for the rest of the season. But Fosse was not among those who thought a deal was imminent.

“I was shocked, though I supposed I shouldn’t have been, the way things were going,” Fosse told the Plain Dealer. “I’m sorry to be leaving Cleveland. I was hoping to finish my career here, but not yet because I know I can play four or five more years.”

Fosse hit .353 with Seattle down the stretch, finishing the year with a .276 batting average.

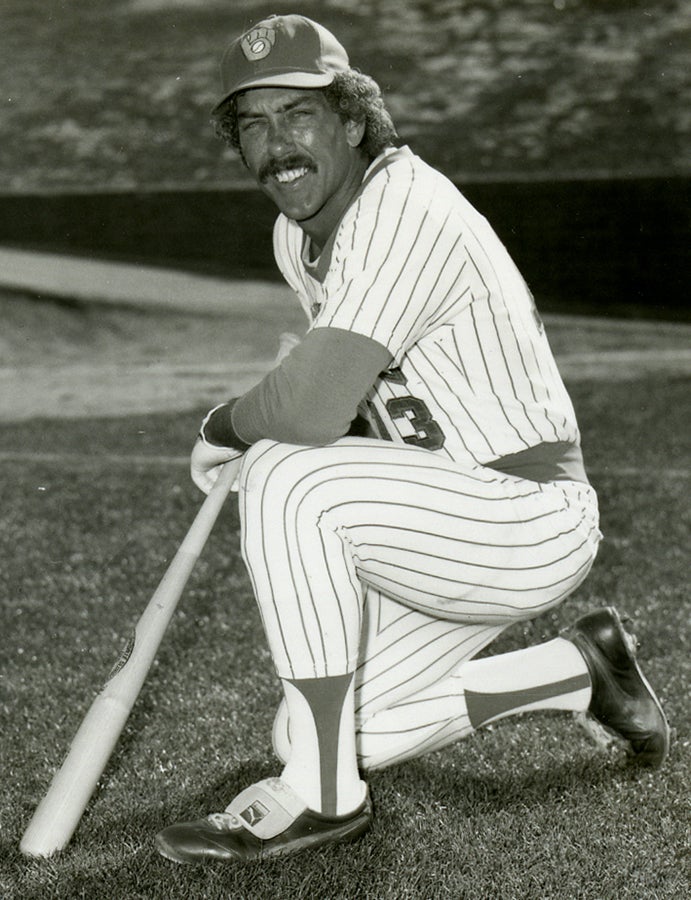

On Nov. 29, the Brewers announced that Fosse and the team had agreed to a three-year deal worth a reported $475,000 – part of a spending spree that saw Milwaukee also add free agent Larry Hisle. But in a March 20 exhibition game in Tempe, Ariz., Fosse stepped on a divot in the baseline and pulled his right hamstring while trying to beat out an infield grounder. He tore knee ligaments on the same play and wound up missing the entire 1978 season.

Fosse came back in 1979 but appeared in just 19 games, hitting .231. On April 3, 1980 – after playing in only two exhibition games due to a recurring stiff neck – Fosse was released by the Brewers.

“Injuries finally caught up with me,” Fosse told the Associated Press. “I’m hoping things will work out with some other club.”

But when Fosse found no takers, his playing career ended. He finished his career with a .256 batting average over 924 games while earning two All-Star Game berths, two Gold Glove Awards and two World Series rings.

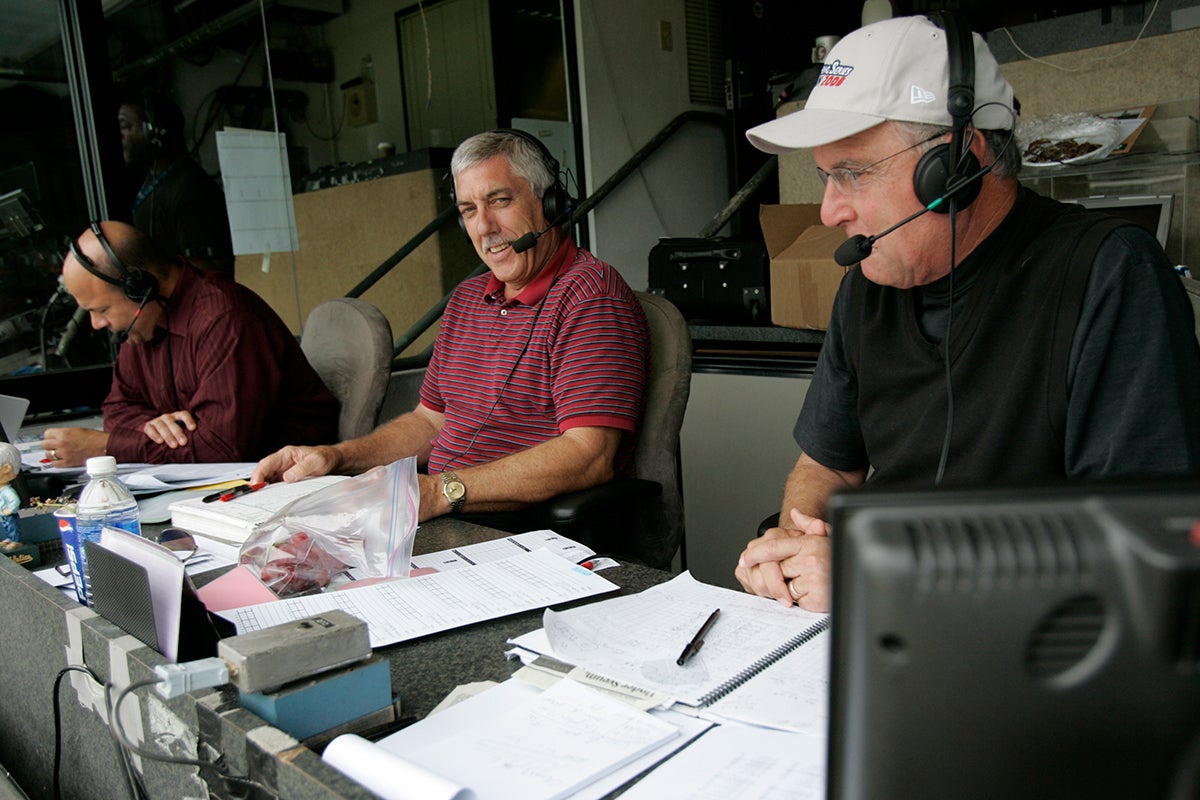

After working in the Athletics’ front office, Fosse became a team broadcaster in 1986 and called Oakland games through 2021, including 33 seasons as a TV analyst.

Fosse passed away on Oct. 13, 2021, after a long battle with cancer. His body ached continually after his 12 big league seasons as a catcher, but Fosse endured and ensured his moment under baseball’s brightest lights would always be remembered.

“That’s something that people will continue to talk about, whether they were alive at the time or watched the video and see the result,” Fosse told the AP in 2015. “As much as it’s shown, I don’t have to see it on TV as a replay to know what happened. It’s fresh.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum