- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: The evolution of baseball gloves

#GoingDeep: The evolution of baseball gloves

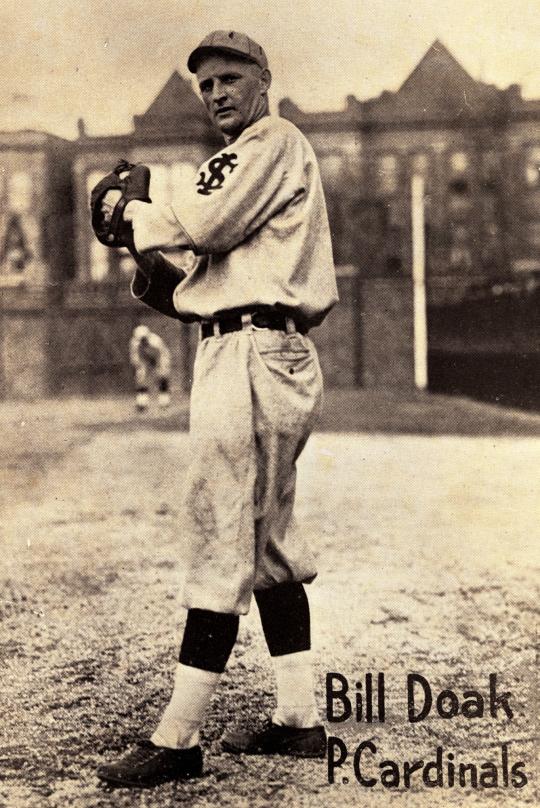

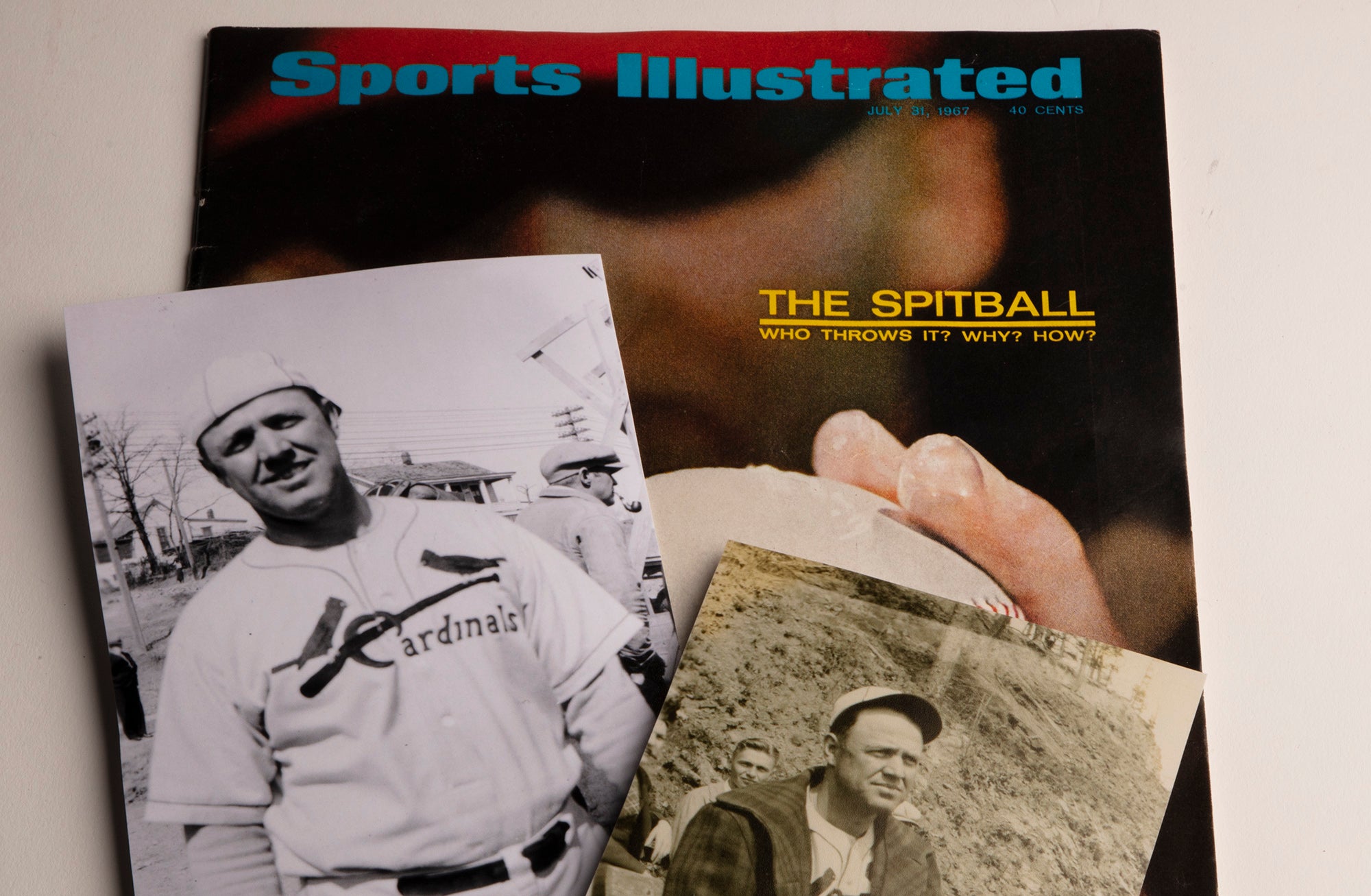

In 1919, Cardinal pitcher “Spittin’ Bill” Doak went to the Rawlings Sporting Goods Company of St. Louis and pitched a new idea in glove design.

Essentially, the plan introduced an adjustable laced web from the thumb to forefinger that formed a deep natural pocket and didn’t need to be broken in.

Little did Doak know that his idea would revolutionize the fielder’s glove as the most important design feature in 50 years. Rawlings rolled out the Doak model to the public in 1920 and hired a chief glove designer named Harry Latina two years later. Gloves soon became indispensable tools of the game.

While some prefer the bat as their trusty tool, it doesn’t quite compare to the connection one has with their glove.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

The evolution of the baseball glove is fascinating, but even more fascinating is piecing together the various stories and accounts from so many differing sources. Many sources and player memories contradict each other. Meticulous research has been done over the years as to the origin of the glove. Author/historians such as Peter Morris, Harvey Frommer and William Curran unearthed many early accounts of players wearing a glove.

It’s common knowledge among baseball historians that gloves first made a brief appearance in the 1860s, grew in the 1870s, were commonplace in the 1880s and were used by most players in the 1890’s.

To tell the story of how gloves evolved over the years, we have to start from the beginning.

References to amateur players donning gloves started to appear as early as the 1860s. In most instances, it was by a catcher using them to protect sore hands. These gloves were oftentimes flesh-colored or light in color as to not draw unwanted attention to them. Players would purchase or repurpose a set of work gloves or tradesmen’s gloves and cut off the fingers. Some players used a bricklayer’s glove while others used driving gloves or a railroad brakeman’s glove.

But no matter the primary source, gloves were utilitarian in nature and not made as sporting goods. They were repurposed from other trades and used for one reason only: protection. Players improvised and used everything from hay to sponges to raw meat as padding. As the pitching rules evolved along with pitch deliveries and the need for catchers to stand nearer the plate, so did the need for protection.

A well-known account of 1869 Red Stockings catcher Doug Allison indicated he wore a set of buckskin gloves to protect his sore hands in 1870. Due to the stature of the Cincinnati club, the publicity cast a wide net and paved the way for others.

Charles Waitt was widely known as one of the first fielders to wear a protective glove in 1875 according to Hall of Famer Albert G. Spalding. Although Waitt was not the first, Spalding wrote:

“The first glove I ever saw on the hand of a ball player in a game was worn by Charles C. Waite (sic), in Boston, in 1875. He had come from New Haven and was playing at first base. The glove worn by him was of flesh color, with a large, round opening in the back. Now, I had for a good while felt the need of some sort of hand protection for myself…For several years I had pitched in every game played by the Boston team, and had developed severe bruises on the inside of my left hand. When it is recalled that every ball pitched had to be returned, and that every swift one coming my way, from infielders, outfielders or hot from the bat, must be caught or stopped, some idea may be gained of the punishment received.

“Therefore, I asked Waite (sic) about his glove. He confessed that he was a bit ashamed to wear it, but had it on to save his hand. He also admitted that he had chosen a color as inconspicuous as possible, because he didn’t care to attract attention. He added that the opening on the back was for purpose of ventilation…Still, it was not until 1877 that I overcame my scruples against joining the “kid-glove aristocracy” by donning a glove. When I did at last decide to do so, I did not select a flesh-colored glove, but got a black one, and cut out as much of the back as possible to let the air in.

“I found that the glove, thin as it was, helped considerably, and inserted one pad after another until a good deal of relief was afforded. If anyone wore padded glove before this date I do not know it. The ‘pillow mitt’ was a later invention.” (America’s National Game, 1911)

A.G. Spalding started the sporting goods company bearing his name in 1876, and his 1877 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide first listed catcher’s gloves for sale.

Austin Butts applied for the first patent on a sporting glove on May 15, 1877, and was granted a patent on Jan. 1, 1878. The Butts glove was similar to a bricklayer glove and used to bear the brunt of the pitched ball. On April 12, 1883, he applied for his second ball glove patent, this time for a fingerless glove. In 1885, George H. Rawlings of St. Louis patented the padded glove.

Providence infielder Arthur Irwin broke a couple fingers on his catching hand in 1883. He had an idea for a protective glove and took it to the J.F. Draper & Co. (later Draper & Maynard). His design was to transform an oversized buckskin driving glove into a padded glove to use on his injured hand so he could play. He continued to wear it after his hand healed and it caught on widely throughout the league. He said he made these gloves for other players as well as companies like Spalding & Reach who ordered them directly for retail sale. D&M then manufactured the Irwin Model for other retailers.

Until this time, gloves were only used at catcher and first base. In addition, the Irwin model further bridged the gap between gloves being homemade to gloves being manufactured as sporting goods and thus work or workman’s gloves now became baseball gloves, or sporting goods.

These were all gloves – protection with fingers up to this point. The mitt or mitten or “pillow mitt” referred to by Spalding had yet to come along. So catchers wore two padded fingerless gloves on both hands up through the mid-1880s. The catching glove developed padded fingers, and a thinner, smaller fingerless glove was used on the throwing hand to allow the catcher to return the ball to the pitcher. This would all change in the late 1880s with Joe Gunson’s design of the round catcher’s mitt…but the credit can’t be given so quickly.

Many claimed to have invented the round mitt, and Morris wrote about it well. While Jack McCloskey, Paul Buckley, Ted Kennedy and Harry Decker all claimed to have invented it, it’s more widely believed that Joe Gunson should be given credit of the idea and that Kennedy took Gunson’s idea and patented it prior to Gunson, who didn’t really worry about such things. In a 1939, hand-written letter by Gunson to William Beattie, Curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Gunson recounts making a mitt out of a glove by sewing the fingers together and using a perimeter wire, belts and sheepskin to be used in two games to be played on Decoration Day in 1888 while playing against Kennedy, the pitcher on the opposing team. Gunson explained his design to Kennedy who was quick to patent an inferior version of Gunson’s mitt. Decker realized the design deficiency then patented a better one more closely resembling Gunson’s.

The use of gloves was nearly universal by the end of the 1880’s. The 1890s saw baseball gloves progress toward fielding tools. Crescent padded heels were sewn on the front exterior of the glove to form a pocket. Webs were sewn between the thumbs and forefingers. They started out large and later became smaller to allow more flexibility. Purists like George Wright thought gloves would give fielders an unfair advantage, yet his company manufactured them. In 1895, the rules committee felt the need to restrict the size of a glove to 10 ounces and no more than 14 inches in circumference. The catcher and first baseman were free to use a glove of any size.

With the advent of the automobile and its gaining popularity, the horse from horse and carriage fame became more and more obsolete. Horses, and their hides, were abundant, so most gloves were made of horsehide after the turn of the century. Cowhide gloves were still years away.

Not much happened during the dead ball era. Reach’s Diverted Seam patent of 1908 was the most important. As glove manufacturers strived for the next best invention, many of them fell flat and are treasured today due to their rarity. Gloves like a duck web (“Duk Fut”) where webs were sewn between all the fingers started to appear around the same time along with ambidextrous gloves. Fielder’s mitts were also produced – mitts that could be worn at any position. The practice of mitts only allowed at first base and catcher did not come until later.

The Draper & Maynard Co. led the way as the preferred glove among professional players and then Rawlings really came on the scene with the introduction of the Doak glove. That changed everything. Harry Latina rolled through the 1930s as the leading glove designer and his son Rollie joined the design team in 1947. Harry crossed paths with Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg who had modified the web of his basemitt to a whopping 13” resembling a fish net, which led to a rule change from the Commissioner’s office in 1939 banning mitts over 12” from top to bottom. It also led to Latina’s revolutionary 1940 basemitt design called the Trapper, which essentially closed around the ball when caught. It was the most exciting and important design feature for basemitts ever. He was king – and then came 1957.

Although there were nearly 100 glove design patents from 1920 to 1957, none were as revolutionary as Wilson’s new glove. In spring training 1957, Wilson introduced a glove designed mostly by the players. According to the first reference in the 1958 Wilson catalog:

“The glove, known as the A2000, has a bigger, longer pocket…the ball stays trapped and caught, yet easy to retract for your split-second throw. That’s the amazing Snap-Action feature! The deep, sewed-in, Grip-Tite pocket allows No Rebound! That ball just can’t pop out again!”

The Snap Action heel was the key to the way gloves look today. It allowed the thumb to close over the fingers when a ball hit the web. The Latinas responded to the A2000 with the XPG model and Trap-Eze in 1959 featuring their new Edge-U-Cated Heel patent. Both the A2000 and Trap-Eze remain extremely popular today.

Harry retired a year later, and Rollie filled his shoes as head designer. Rawlings led the way through the 1960s. The 60s experimented with different hides like kangaroo, which was lighter and softer but not as durable. The same was true of buffalo leather.

The 1980s and 90s saw the use of synthetics and other artificial materials, which were lighter and more durable but design features tailed off slightly. After Wilson’s game-changer, and the leading Rawlings patents of the 60s, gloves changed very little, and new patent features were subtle.

Glove design has come a long way in its journey from protection to performance. When showing someone a vintage glove, the response is always the same: “How did they ever catch with these!”

Jim Daniel is a baseball glove historian and enthusiast and resides in Huntington Beach, Calif.