- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: By using grandfather clauses, baseball history often comes full circle

#GoingDeep: By using grandfather clauses, baseball history often comes full circle

A baseball is a work of art.

For the official Rawlings Major League Baseball, that work is done in Costa Rica, where skilled hands sew together two pieces of cowhide over a ball of yarn with a rubber core inside – 216 red thread stitches altogether.

Even in repose, the five-ounce baseball is a thing of beauty. In motion, either off the hand of the thrower, or the bat of the hitter, it takes on a compelling life of its own.

Baseball – The National Pastime – is also worthy of our fascination. It’s been sewn together by players and executives, fans and umpires, writers and broadcasters, over the course of a century and a half. But as such, it is a work in progress. Every now and then, Baseball, the one with the capital B, needs a little doctoring.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Which brings us to the “Grandfather Clause,” a provision applied to a new rule the way, say, Burleigh Grimes applied a coating of saliva to the ball he was about to pitch. Grimes was trying to win games and further his career with added spin.

The executives are also hoping to change the flight of the game, and the grandfather provision is their way of slipping one by their opponents. Yes, it can be a little messy, but it is an attempt at fairness.

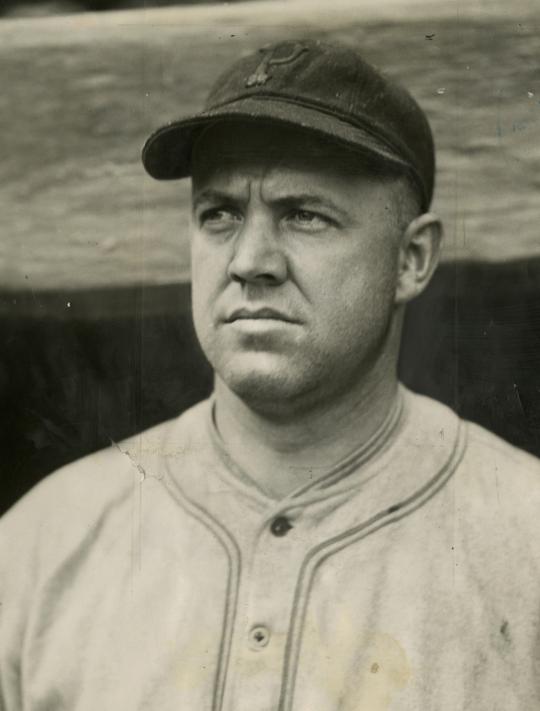

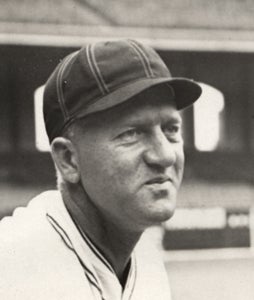

The most famous example of this kind of bargain came in the offseason between 1919 and 1920, when both leagues decided to ban the spitball. But eventually, they exempted 17 practitioners of the pitch, including three Hall of Famers: Red Faber, Stan Coveleski and Grimes.

The grandfather of grandfather clauses in organized baseball was born in infamy. It came about after a July 14, 1887, meeting of the directors of the International League in Buffalo. As the Newark (NJ) Daily Journal reported:

“The International League directors held a secret meeting… and the question of colored players was freely discussed. Several representatives declared that many of the best players in the league are anxious to leave on account of the colored element, and the board finally directed Secretary White to approve of no more contracts with colored men.”

The color line had been drawn, but there were still some valued Black players in the league, such talents as pitcher George Stovey and catcher Moses “Fleetwood” Walker in Newark, second baseman Frank Grant in Buffalo, second baseman Bud Fowler in Binghamton and pitcher Robert Higgins in Syracuse. To be fair to them and their teams, it was decided that they would be permitted to keep playing, and thus they were “grandfathered” in. Soon enough, though, they saw the writing of bigotry on the wall. As irony would have it, when Fleet Walker stopped playing for Newark in 1889, he would become the last African-American in the International League until 1946, when Jackie Robinson joined the Montreal Royals.

The next significant use of the grandfather clause came 33 years later with the spitball ban. It was quite literally a loaded question that mirrored the Wet vs. Dry arguments of concurrent Prohibition. Never mind that heretofore, two of the greatest pitchers had been spitballers – Jack Chesbro (41-12 for the New York Highlanders in 1904) and Ed Walsh (40-15 for the 1908 Chicago White Stockings). Detractors, led by owners Calvin Griffith of the Washington Senators and Barney Dreyfus of the Pittsburgh Pirates, claimed that the spitter was unsanitary, dangerous, hard on pitchers’ arms, difficult to field and, most importantly, difficult to hit. Moreover, Babe Ruth had just captivated America with his 29 homers in 1919, and the owners wanted more of the same. And so, on Feb. 9, 1920, the joint rules committee voted to ban the pitch, along with other doctored pitches like the “mud ball,” “shine ball” and “emery ball.”

Realizing this might be a shock to the system, the American League announced that each of its eight teams could designate two pitchers who would be allowed to use the spitball during the 1920 season, while the National League merely allowed its spitballers to continue without a team quota. All in all, 13 teams offered up 22 names, with the Senators, Pirates and Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s passing. The assumption was that the grace period was only for a year.

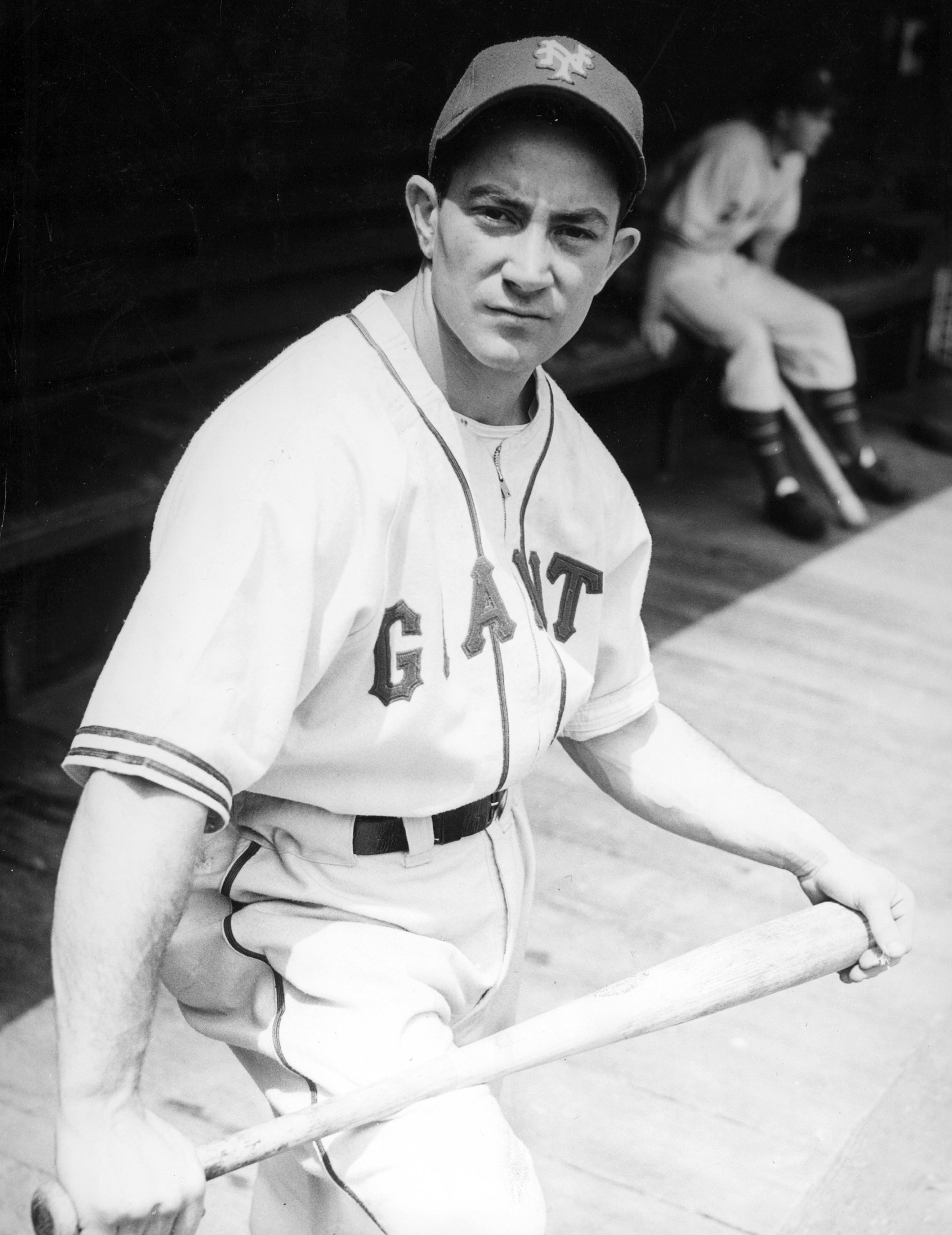

Enter Bill Doak, the St. Louis Cardinals pitcher. According to Spitballers: The Legal Hurlers of the Wet One, a wonderful book co-authored by Charles F. Faber and Richard B. Faber, it was Doak who spearheaded a campaign to allow spitballers to continue use of the pitch throughout their careers: “The effort got under way during spring training and was carried on in a quiet but effective manner all summer.” The practitioners also did themselves a favor by having very successful seasons: Coveleski, Grimes, Faber, Doak and Urban Shocker all won 20 or more games, while Jack Quinn won 18.

Early in the spring of 1921, both leagues agreed to allow regular spitballers to continue throwing their specialty. There were 17 in all – nine in the American, eight in the National. Taken as a whole, they were a remarkable group who did more than just put slippery elm cough drops in their mouth to increase their flow of saliva.

There were the Hall of Famers: Faber, Coveleski and Grimes. There was Doak, who became the Edison of Leather by suggesting to Rawlings in 1920 that they make a glove with a web between the first finger and the thumb. Ray Fisher, a Vermonter who taught Latin in the offseason, pitched for the Reds against the 1919 Black Sox, then went on to coach the University of Michigan baseball team for 38 years. Shocker, who had four 20-win seasons for the St. Louis Browns and 18 victories for the ’27 Yankees, pitched with a heart condition that forced him to sleep standing up. Quinn, who won 247 games in his 23-year career, pitched his last major league game at the grandfatherly age of 49.

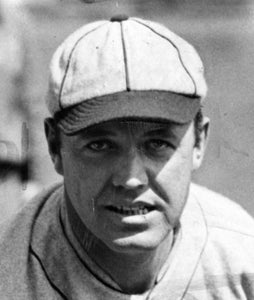

As for Grimes, he kept throwing the pitch until Sept. 20, 1934, when he appeared in relief for the Pirates and struck out Jersey Joe Stripp in a 2-1 loss to the Dodgers. That was the last legal spitter.

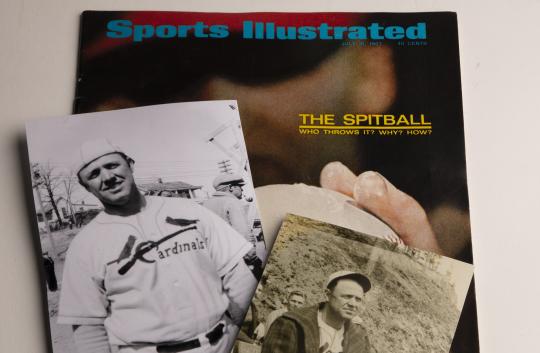

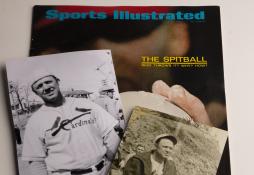

But the pitch lived on. It’s meant to sink, so naturally, it went underground. Umpires ejected Nels Potter of the Browns on July 20, 1944, for throwing a spitter while he was shutting out the Yankees in the fifth. Saliva gave way to shaving cream, hair tonic, olive oil and the emery boards. Doctored baseballs became so pervasive that Sports Illustrated did a cover story on “The Infamous Spitter” for its July 31, 1967 issue.

In the story, names like Lew Burdette, Dean Chance, Jack Hamilton, John Wyatt, Phil Regan, Don Drysdale and Gaylord Perry were named, while a 73-year-old gentleman farmer from Trenton, Mo., waxed poetic about the pitch. “I like to sit in this easy chair by the window here,” said Burleigh Grimes. “That way I can look out at the birds and animals that come right up to the back lawn… I think to myself that everything I’ve got I owe to the spitball.”

The July 31, 1967, edition of Sports Illustrated featured a story on the spitball, which had been outlawed for more than 45 years at that time but was still in vogue in the big leagues. Hall of Famer Burleigh Grimes was the last pitcher allowed to throw the spitball. (Illustration by Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

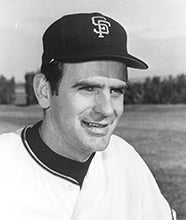

Even after the story came out, instances of enforcement were rare. Regan, a Cubs reliever, was tossed for a loaded ball in 1968. Though long suspected of throwing a spitter, Perry wasn’t ejected from a game until he was 43 and pitching for the Mariners in his 21st season (Aug. 23, 1982). Nine years later, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Age was no excuse for Gaylord, but it was when Fenway Park and Wrigley Field were grandfathered in 1958 and allowed to retain their outfield dimensions after Major League Baseball passed a rule stating that new ballparks had to have a minimum distance of 325 feet from home plate to the left and right field foul poles, and 400 feet in center. Fenway falls a little short on all three counts, while true center at Wrigley is 390 feet away from home. Now that both stadiums are over 100 years old, we dare you to try and move them.

Adding to the anachronistic feel of Fenway in the 1970s was the Red Sox backup catcher, Bob Montgomery. In December of ’70, Major League Baseball mandated that all players wear helmets when stepping into the batter’s box, though it did allow players already in the majors to eschew the added protection. Only three players had the temerity not to do so: Norm Cash, who retired after the ’74 season; Tony Taylor, who called it quits after ’76, and Montgomery, who played until 1979.

Montgomery, who was fearless enough to fly his own plane, once said, “Helmet? That’s what my skull is for.” Now 78 and sharp as a tack, he still jokes: “They didn’t throw at .250 hitters. But I did wear a protective liner inside the hatband of my Red Sox cap. And I did wear a real batting helmet one time. It was in the minors when I was playing for Louisville, and a wild left-hander named Balor Moore was on the mound, throwing from out of the state fair’s Ferris wheel in center field.”

When Montgomery hit into a double play in the ninth inning of the Red Sox’ 16-4 loss to the Orioles on Sept. 9, 1979, he became the last player to go to bat in a major league game without a hardhat. Somehow, he finished that season with a .349 average and his career with only seven HBPs.

That last hat he wore is in the Museum’s collection of artifacts.

Starting with the 1971 season, MLB mandated that all batters wear protective helmets but allowed players already in the big leagues to choose to eschew the headgear if they so decided. Bob Montgomery was the last player to bat without a helmet when he came to the plate on Sept. 9, 1979. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“They asked me for it when they had an exhibit on the evolution of the batting helmet,” he says. “I actually saw it there when I went to see my old teammate Jim Rice inducted in 2009. I may not be in the Hall of Fame, but my hat is.”

So are two other artifacts belonging to “grandfathers.” One is the “balloon” outside chest protector that belonged to Jerry Neudecker, an American League umpire from 1966 until 1985. The AL had decided in 1977 to phase them out and adopt the inside protectors the NL was using, but veterans like Neudecker were allowed to wear the old one.

Oakland A’s manager Billy Martin once said of Neudecker: “He’s so incompetent that he couldn’t be a crew chief on a sunken submarine.” But his peers thought differently – they voted him Umpire of the Year after the 1980 season. He was behind the plate for Catfish Hunter’s perfect game in 1968 and for the Pirates’ 1979 World Series Game 7 victory over the Baltimore Orioles. His final game behind home plate was on Oct. 5, 1985, when the Toronto Blue Jays clinched their first AL pennant with a 5-1 win over the Yankees at Exhibition Stadium.

Umpire Jerry Neudecker was the last AL umpire allowed to wear an outside chest protector as the league slowly phased in the "under-the-uniform" kind. Neudecker's equipment is now part of the collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

That was the last game for a regular big league umpire who wore one of those big outside protectors. And Neudecker wore it well – when he passed away at the age of 66 in 1997, fellow umpire Bruce Raven said: “He had a big heart.”

Like the protector, he wore that on the outside, too. At the time of his death, Neudecker was training a new generation of umpires.

The other artifact is a size 7 1/8 Florida Marlins helmet worn by Hall of Famer Tim Raines. “Rock” had made seven All-Star teams with the Montreal Expos while leading the NL in stolen bases four times and winning the batting title (.334 in ’86), spent another four years with the White Sox and won two World Series rings with the Yankees. So why the Marlins, with whom he finished his career in 2002?

Well, it just so happened that Raines was the last player to wear a batting helmet without earflaps. In 1983, four years after Raines arrived in the majors, MLB mandated that all players wear helmets with ear protection. Exemptions were made, however, for veterans who had submitted written requests. By 2002, Raines was the only writer left.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Major League Baseball retired his number, 42, in April of 1997. One little problem: 13 players already had that number.

So they were “grandfathered” and allowed to keep the number. For the record, and trivia contests, the players were Butch Huskey, Mike Jackson, Scott Karl, Jose Lima, Mo Vaughn, Lenny Webster, Tom Goodwin, Marc Sagmoen, Kirk Rueter, Jason Schmidt, Dennis Cook, Buddy Groom and Mariano Rivera.

By the start of the 2004 season, all but one of them had retired from baseball: Rivera. The Hall of Fame reliever hadn’t asked for the number when he first showed up in Yankee camp in 1995 – clubhouse manager Nick Priore gave it to him. But 42 figuratively came to grow on him. “I decided I better learn about him and understand what he was all about,” Rivera recently told MLB.com’s Mark Feinsand.

Just months after Rivera retired after the 2013 season, he was given the Jackie Robinson Foundation Humanitarian Award.

While Rivera may have been the last major leaguer to wear No. 42, a man who actually knew Robinson was also given dispensation to wear the number. He is Art Silber, the owner of the Class A Fredericksburg Nationals. He grew up in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, near Ebbets Field. “We hung around the ballpark all the time,” says Silber, now an 82-year-old actual grandfather of three. “He and Roy Campanella would often talk to us and sign our baseballs.”

Later in life, Silber became a successful banker and minor league owner, and came to know Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow. When the major leaguers who wore his number were grandfathered in, so was Silber, who coached first base for his team, the Potomac Nats.

He stopped coaching a few years ago, but his new team, the FredNats, is located at 42 Jackie Robinson Way in Fredericksburg, Va., and every year, they conduct a Jackie Robinson Essay Contest. “He changed so many lives,” says Silber. “He certainly changed mine.”

The purpose of baseball is to get back to the place where you started. So there’s a certain poetic justice in the history of the game’s Grandfather Clause. It was first used to help draw the color line in baseball. One hundred and ten years later, it was used to honor the man who erased it.

Steve Wulf is a freelance writer from Larchmont, N.Y.