- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: The year Sacramento became the home run capital

#GoingDeep: The year Sacramento became the home run capital

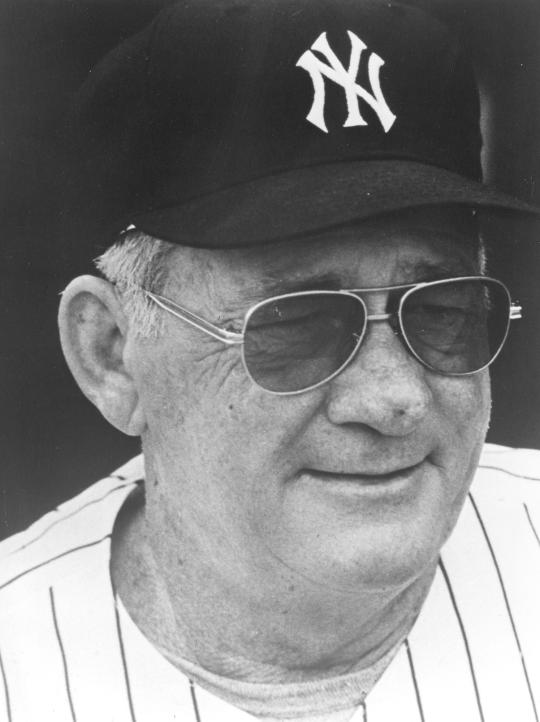

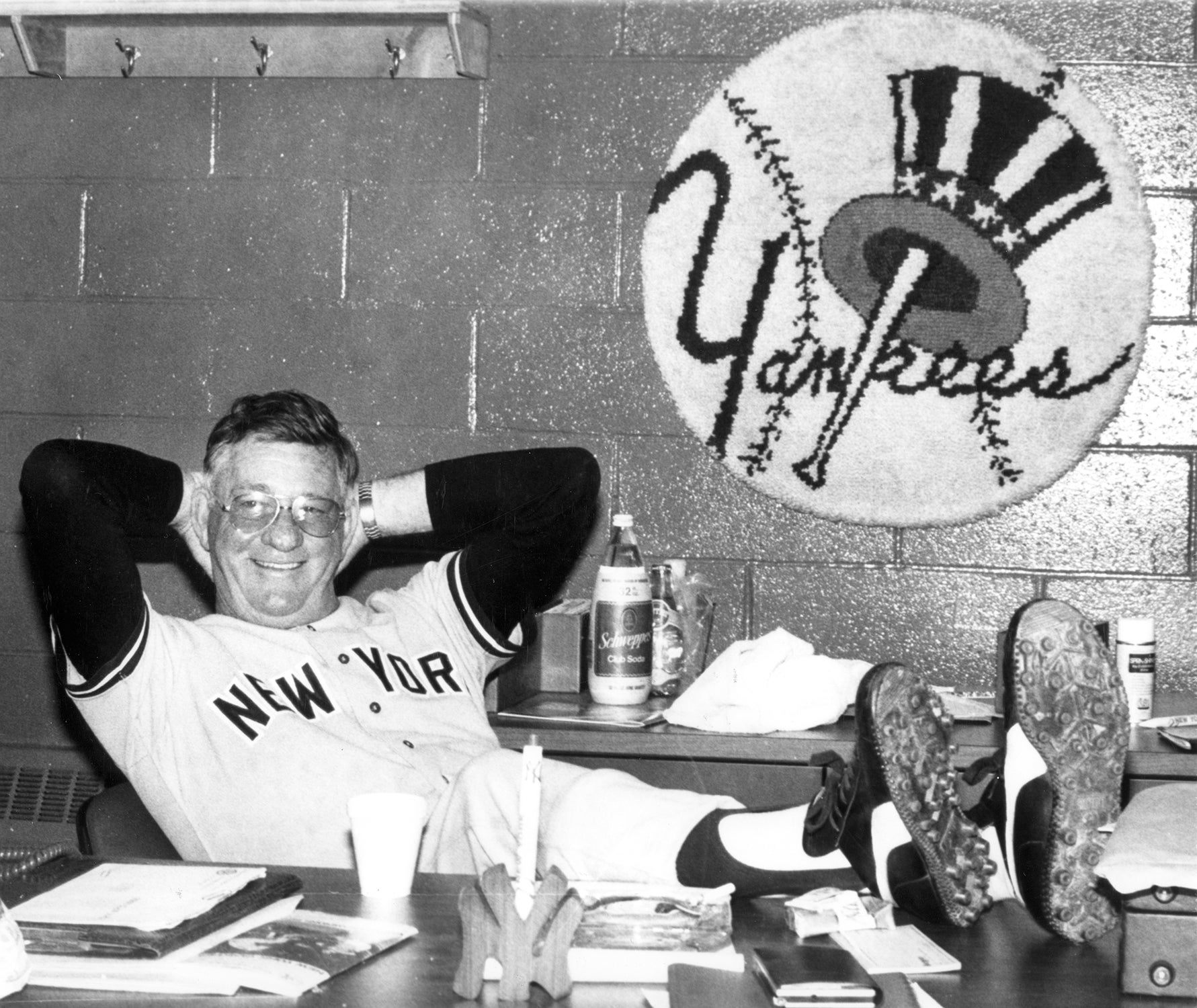

Three decades after serving a three-year hitch in the United States Navy during World War II, Bob Lemon was now witnessing an unprecedented baseball bombardment.

As the new manager of the Pacific Coast League’s 1974 Sacramento Solons, the Triple-A affiliate of the Milwaukee Brewers, the former star pitcher and future Hall of Famer was now tasked with leading a group of players on the cusp of the big leagues.

But the veteran skipper, who had already spent time managing PCL teams in Seattle and Vancouver as well as being only a few seasons removed from three years leading the Kansas City Royals, was soon to find himself – thanks to a uniquely reconfigured home ballfield – guiding a team that would set a minor league record with 305 home runs.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

“There’s no way to evaluate players when we’re playing at home. A guy who hits four homers in a game here might have had four fly outs in a normal stadium,” said Lemon, who gave up 180 homers but won 207 games during a 13-year major-league career that ended in 1958, in a midseason interview. “And a pitcher’s earned run average means nothing. But I’ll tell you one thing – if a guy can pitch effectively here, he can pitch effectively anywhere.

“We try to do most of our judging on the road. It’s like pro basketball. You call a timeout in the last two minutes and that’s when the game is won. I let them play for eight innings and then try to win it. You never have it won and you’re never out of it. We’re supposed to judge the other clubs, too, but I do it with what I see at their place,” added the Class of 1976 Hall of Famer. “You have to pity pitchers in our park. There have been home runs the shortstops could have caught. There’s no use me explaining it to you. It’s like trying to explain your first love affair. You just have to try it.”

The explanation as to why a shortstop should have been able to catch a home run ball was a left field fence 233 feet from home plate.

Prior to the start of the 1974 PCL season, the Eugene Emeralds, after it was determined the city could not support a Triple-A franchise, moved down the coast from Oregon to Sacramento. California’s capital city had been without a minor league team since a longstanding PCL squad dating back to the first decade of the 20th century left after 1960. What this latest incarnation discovered, though, was their previous ballpark, Edmonds Field, had been demolished.

Left with no other option, the latest version of the Solons found a home at 22,000-seat Hughes Stadium, a horseshoe-shaped edifice built in 1928 as a football and track facility on the campus of Sacramento City College. The stadium, which had also played home to motorcycle and auto racing over the years, would now host baseball for the first time. But converting this football/track site to a baseball park came with its own problems.

The field’s dimensions were 390 feet to dead center and the right field fence was 300 feet from home, but it was the eyepopping short leftfield distance that caused the most tumult. Minor League Baseball waived organized baseball’s 250-foot minimum outfield dimensions for the 1974 season only.

“Our original projection,” explained Solons general manager John Carbray at the time, “was for a 261-foot left field barrier, plus the existing 40-foot-high fishnet, but we lost 19 feet in the conversion of the stadium. And we were not permitted to encroach on the school track facilities behind the wall.”

Bob Lemon began his big league managerial career with the Royals in 1970 but found himself back in the minors with Triple-A Sacramento in 1974. Lemon later returned to the big leagues with the White Sox and then the Yankees, whom he managed to the 1978 World Series title. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In an attempt to lessen home runs, the team erected a 40-foot screen from the leftfield foul pole all the way to the power alley in left-center.

Subsequent measurements placed the left field wall at 233 feet with a 140-foot-long barrier 40 feet above the fence. The stadium’s running track ultimately constricted its baseball dimensions. The left field screen was nicknamed “Mount Sacramento,” while a newspaper contest named the short porch in leftfield “Camellia Gardens,” the camellia the city’s official flower.

“Being a former pitcher, I’ve always emphasized pitching and defense,” Lemon said before the season. “Hughes Stadium could persuade me to change some of my strategy. We’ll have some very exciting baseball with plenty of big innings. The last out will really count in this park.”

Lemon was looking at his new job with the Solons – a nickname used by the Sacramento franchise from 1936 to 1960 and referencing an ancient Greek lawmaker as it pertains to the city’s importance as the capital of California – as his best opportunity to manage in the majors again.

“I think the best way to do it,” said the 53-year-old Lemon, who had served as a special assignment scout with the Royals the previous season, “is to manage somewhere in the minors and do a good job.”

Lemon would eventually return to the managing in the majors with both the White Sox (1977-78) and Yankees (1978-79, 1981-82), winning the 1978 World Series with New York.

Possibly foreshadowing the challenges during his tenure in Sacramento, Lemon made it to the Brewers Spring Training site in Arizona a day late from his home in California due to gas shortage laws at the time, his car having an even numbered license plate and he couldn’t fill his tank for the trip.

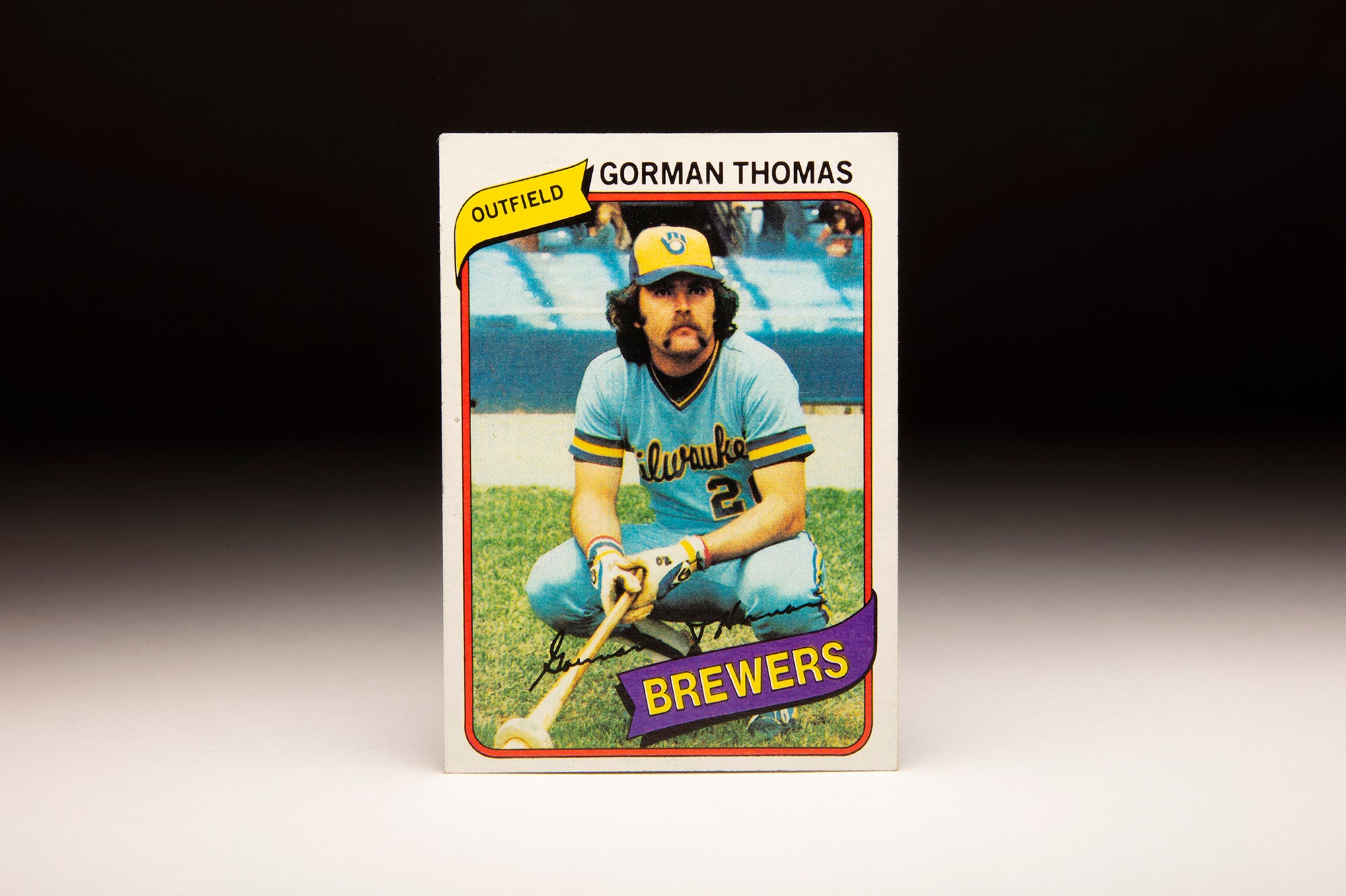

Little did Lemon know what was in store for him and the team, made up of young and veteran Brewers farmhands. Sixto Lezcano, Jack Lind, Larry Anderson, Carlos Velázquez, Ken Wright, Gorman Thomas, Tom Hausman, Rob Ellis, Bob Hansen, Bill McNulty, Roger Miller, Bob Sheldon, Bill Parsons, Bill Castro, Tommy Bianco, Jerry Bell, Bill Travers, Art Kusnyer and Tommie Reynolds were all players from the 1974 Sacramento Solons who played in the Major Leagues during their careers.

Parsons, 25, who had previous success with the Brewers when he won 13 games in both 1971 and ’72, saw the writing on the wall early in the Solons’ season: “Our pitching staff will be ready for the nut farm at the end of the season. A guy could have a great season here and wind up with an earned run average over 10 a game.”

Parsons bemoaned his first game pitching in Sacramento, recalling it “wasn’t so bad until the sixth or seventh inning. It was 4-3 and I made a good pitch in on a left-hander. He hit it four rows up. That did it. I lost 10-8 or something. The more you concentrate, the more frustrating it is. You make a good pitch, jam a guy and he hits it out. If that happens in a decent park, you say OK, but here you can’t get an indication of how well you’re pitching. You could give up three fly balls in the first inning and be out of there, when you might have pitched a shutout. All it means is you didn’t keep the ball on the ground.”

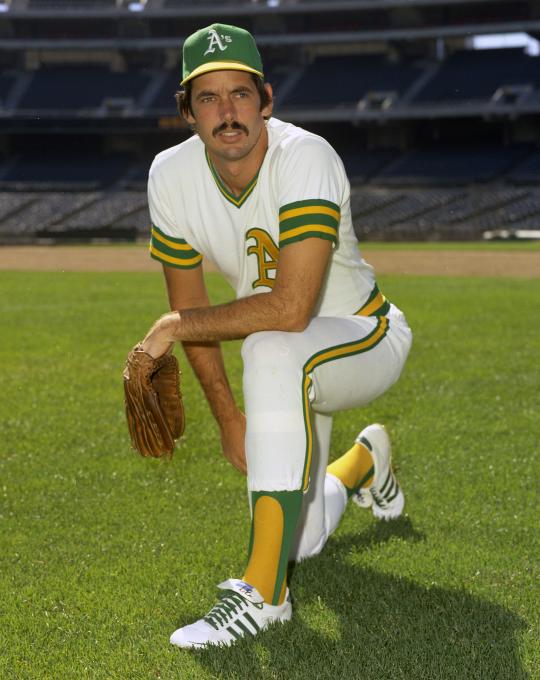

By midseason, Parsons had seen enough and requested a trade. His wish was granted when on June 4, 1974, he was shipped to the Oakland Athletics with cash for veteran slugger Deron Johnson

“It’s ridiculous,” Parsons said when explaining his trade request. “There’s no way to describe it. It’s gotten so bad they don’t let the fans into the stands until right before game time. They’ve lost too many balls. On our opening night here, the club lost eight dozen balls hit out during batting practice. Now they have groundskeepers stationed in the left field stands until right before game time. They’ve lost too many balls.

“There’s no way you can tell how you’re pitching in this park. But I feel I’m pitching good and I’m not going to quit.”

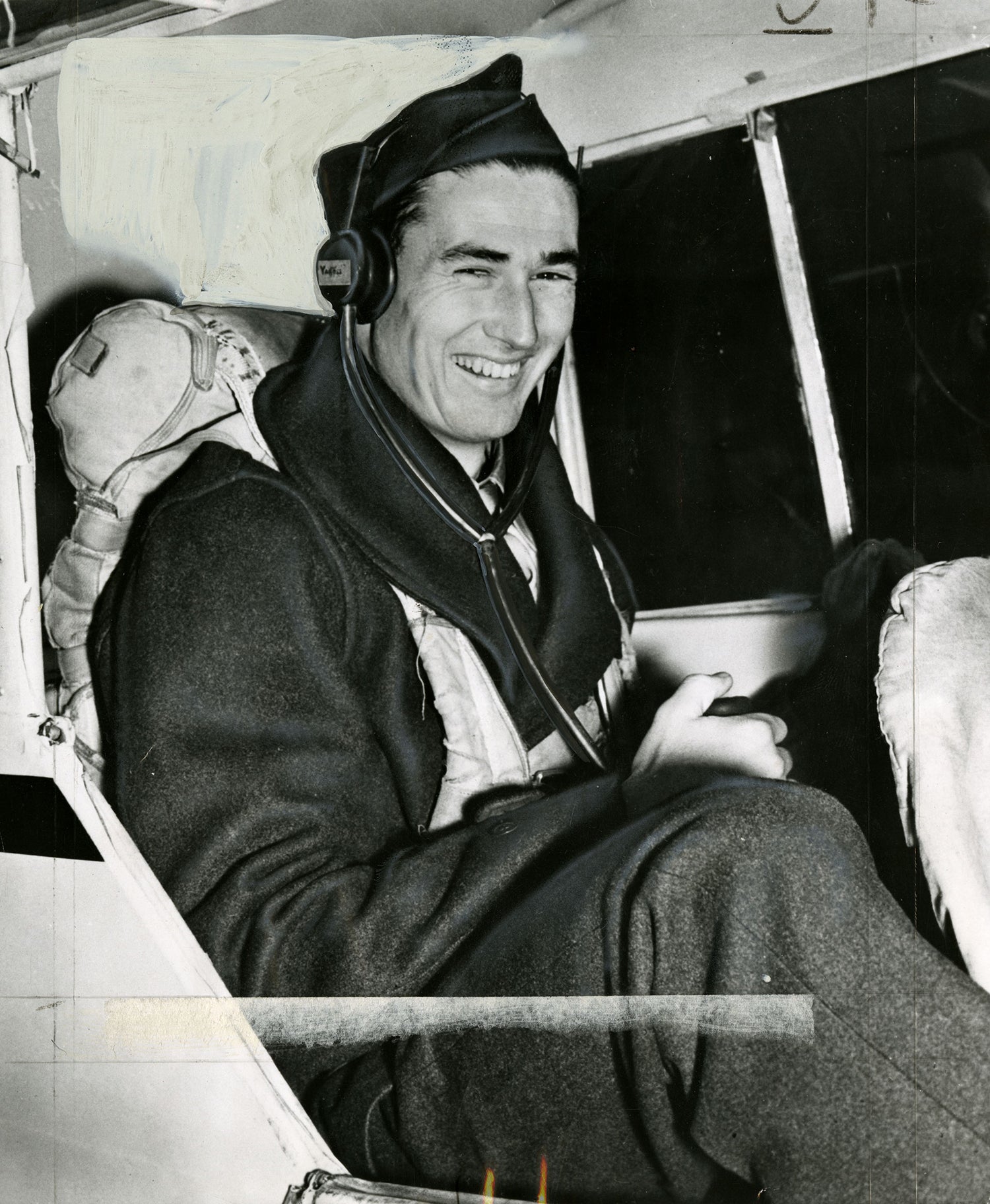

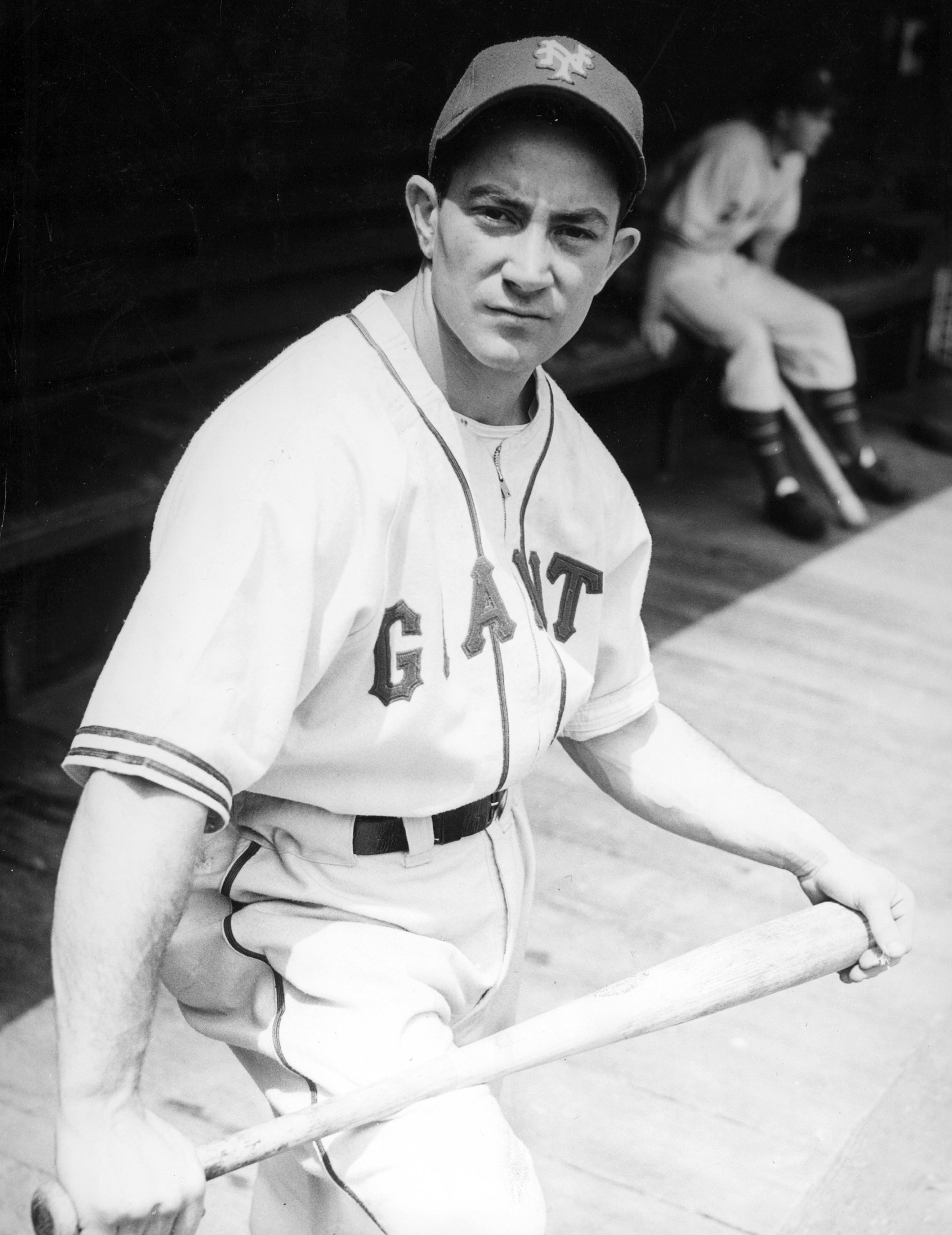

Bill Parsons won 13 games for the Brewers in both 1971 and 1972 but found himself back in the minors in 1974 with Milwaukee's Triple-A team in Sacramento. The bandbox dimensions of Sacramento's park were so frustrating for Parsons that he requested a trade, and the Brewers sent him to Oakland on June 24, 1974, in exchange for Deron Johnson. (Doug McWilliams/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Overall, of Sacramento’s record 305 home runs hit in 1974, 250 were hit at home. Counting the visiting team’s batters chipping in with another 241, the total was 491 homers at Hughes Stadium. And that, too, became a minor league record. Twice during the season, a record 14 homers were hit in a single game.

Third baseman Bill McNulty, a Sacramento native who would go on to lead the minors with 55 homers – 44 at home and 11 on the road – in 1974, had sympathy for those toeing the rubber at Hughes Stadium: “I feel sorry for any pitcher who has to throw in our park, and I particularly sympathize with Bill (Parsons). He’s a flyball pitcher in a flyball stadium. It’s downright embarrassing when a routine pop fly goes for a homer.

“There’s very rarely a double or triple in the park, particularly to left. You either hit it over the screen for a homer or into the screen for a single. When visiting teams first came in this year, guys were hitting balls off the wall – doubles anywhere else – and getting thrown out at second base by 30 feet. The left fielder can have the worst arm in the world and it won’t hurt your club. The shortstop could cover left field and we could use the left fielder at rover.”

Phoenix manager Rocky Bridges joked of having a pitcher he thought was an atheist. “Then I told him he was starting in Sacramento and the next time I saw him he was carrying a bible and beads.”

Others on the Solons shared similar horror stories regarding their home field.

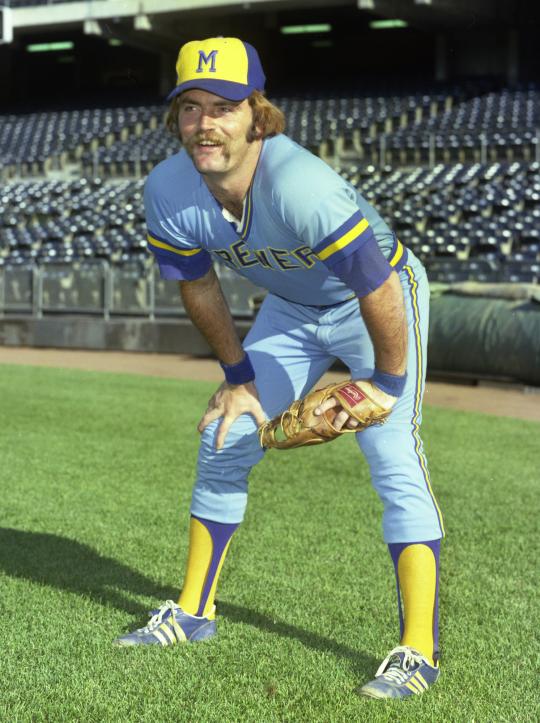

“Gorman Thomas hit a ball the other night that was in on his fists,” Lemon said. “It sounded like he hit it with a piece of flabby meat. It landed in the fourth row.”

Pitcher Jerry Bell, sent down to the Solons by Brewers in May, repeated what someone told him about Hughes Stadium prior to his arrival: “You always think guys are exaggerating. But there’s no way you can exaggerate this ballpark. You just have to look at how the ball is moving, how your stuff is and not worry about anything else. I think the word is around and that they’re not looking at any statistics…that come out of this ballpark. One scout told me not to worry, that if he came to see me he’d only look at how I was pitching.”

Even opposing hurlers, such as Salt Lake City’s John Cumberland, had their opinions: “You have to believe me. If a pitcher doesn’t have his head on straight – especially the young Sacramento pitchers – he’ll probably go to an insane asylum.”

“It’s a Little League park with a big screen,” said Salt Lake City manager Norm Sherry after his team’s first series in Sacramento.

After the Brewers played an exhibition at Sacramento on June 3, Milwaukee pitcher Jim Colborn, who tossed three scoreless innings in the game, said, “This park is a freak – it’s like playing whiffleball in your backyard.”

Solons catcher Art Kusnyer agreed: “You see some of the weakest home runs you can see. It’s a joke.”

Weak or not, the balls were flying out of Hughes Stadium at a record pace in 1974. Sacramento, which averaged a league-best 6.51 runs per game, had five of the top eight minor-league home run hitters in 1974. McNulty was first with 55 homers, Thomas was second with 51, Sixto Lezcano’s 34 was fifth, and Stephen McCartney and Tommy Reynolds each hit 32 and tied for sixth.

“It’s great for the fans, great for the gate and a great way to promote baseball in this town,” said McNulty in an August interview. “But it’s a definite disadvantage. In this park you never try to hit the ball anywhere but to the left. There are no doubles or triples. If anybody is going up to the big leagues, what good does it do him? They say, ‘Well, look where he plays.’ I feel in all honesty I ought to have 33 or 34 home runs. They might think my 44 should only count for about 20.”

Thomas, who would hit 268 home runs in a 13-year major league career, told a newspaper reporter in an August interview that Hughes Stadium was a “joke.”

“When I talk contract with Milwaukee next year, I figure I’ll have 50 homers, and they’ll say, ‘Look where you played, in Sacramento,’” Thomas said. “I’ve been keeping track of the homers I’ve hit here, and I figure I’ve had eight or nine dinks into the stands. The rest would be out in any park. But who’s going to believe it at the end of the year? There have been a lot of cheap homers here, and I hit one of the cheapest with a broken bat.”

On the pitching side, Sacramento’s mound crew finished last in the eight-team PCL with a 6.70 ERA, outpacing the Salt Lake City’s second-worst 5.12 ERA. The Solons offense led the circuit with 937 runs scored, while their 1,030 runs allowed also topped the league.

Tom Hausman, who paced the team with 12 victories, gave up a league-high 50 homers in 180 innings, while teammate Gary Cavallo was second with 40 in 116 frames. Roger Miller, 19, led the staff with 185 innings pitched and a 4.48 ERA.

“One June 4, I had a 9-3 lead against Tacoma with two outs in the ninth and nobody on ninth. Then they hit four consecutive homers off me, and another against my reliever,” recalled Hausman, who said he was in the clubhouse in tears when he got word that Sacramento lost, 10-9.

“I’ll try to forget, but I’ll never get that game out of my mind as long as I live. This place had me on the verge of quitting, but if there’s one thing I got out of it, it is this: No manager ever will have to come to the mound and tell me the game is never over until the last man is out. Even if they lengthen the fence to 250 or 260 feet, I don’t want to come back. I’ll miss the fans, though. They stuck with this team through some tough times.”

Imagine the surprise when Spokane’s Steve Dunning tossed a no-hitter at Sacramento on Aug. 16, winning 10-0 while fanning 14 and walking three.

“I’ll tell you one thing,” said Lemon. “I would have liked to have had a dollar down against those odds.”

Amazingly, despite finishing with a 66-78 record, good for last place in the PCL’s West Division, Sacramento led the minor leagues with a total attendance of 295,831.

“A lot of the fan support is due to the field,” said Carbray in June. “We’re in last place and playing terrible baseball a lot of nights and people are still talking about it and coming out.

“We have had no promotions … What we are selling is a product called baseball and our fans like it. Hank Greenberg was here for the Spokane series and he marveled at our fans. He said our left field screen reminded him of Boston’s left field wall.”

After the season, Lemon reflected on what would prove to be his only season in Sacramento.

“Nobody’s happy finishing last, but if it helped baseball get started in this town again, it was worth it,” Lemon said. “And we had some exciting players. Seven went to the majors and I’m sure some of them will stick. That’s always satisfying to a manager.”

In 1975, the Solons would reorient the Hughes Stadium field, adding a 251-foot left field fence to meet baseball’s minimums, remaining in Sacramento through the 1976 season. Home run totals dropped to 196, as did their attendance to 252,201. The state capital returned with a new stadium to the PCL in 2000 as the River Cats, an A’s affiliate through 2014 and a Giants affiliate since.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum