- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Ted Williams Heads Back to War

#GoingDeep: Ted Williams Heads Back to War

Two weeks after belting a home run off Dizzy Trout in his final game at Fenway Park in the 1952 season, Ted Williams was stationed in Willow Grove Air Station in Willow Grove, Pa., no longer exulting over a ball that rocketed over a fence, but mourning a colleague whose plane had rocketed out of control.

In his first of what would be 17 months of service in the Marines during the Korean War, Williams was in his bunk when he heard a startling “swish” sound overhead. He looked up in the clear springtime sky to see a burning F-9 jet, zooming toward a nearby field.

After serving his country for three years during World War II, Williams had seen most everything. But what he saw on that day in 1952 was something entirely out of his comfort zone.

“They’d found the canopy off to one side,” he said. “But they couldn’t find the pilot; he’d apparently ejected. Then they dragged out a shoe with a foot in it. The worst thing I’d ever seen.”

What he didn’t know at the time, was that in less than a year, he too would find himself in a burning F9F panther jet, barreling toward the ground. But unlike the unfortunate pilot at Willow Grove, Williams lived to tell the story.

In 1952, the United States was two years deep in the Korean War, and sorely in need of trained pilots. This conflict was a complicated one. The wound that World War II had left on American citizens was seven years old and still fresh – no one was eager to rush back onto the battlefield. It was at this time that the country began to feel disillusioned with war, and since the conflict in Korea made no tangible effect on the American way of life, it has been referred to in hindsight as “forgotten.”

“It was widely indifferent,” Jerry Coleman, a Yankee infielder who had also been called to serve in Korea, told USA Today. “World War II captivated the attention of this country like no other war. But the Korean War was something you hoped to survive and come back home.”

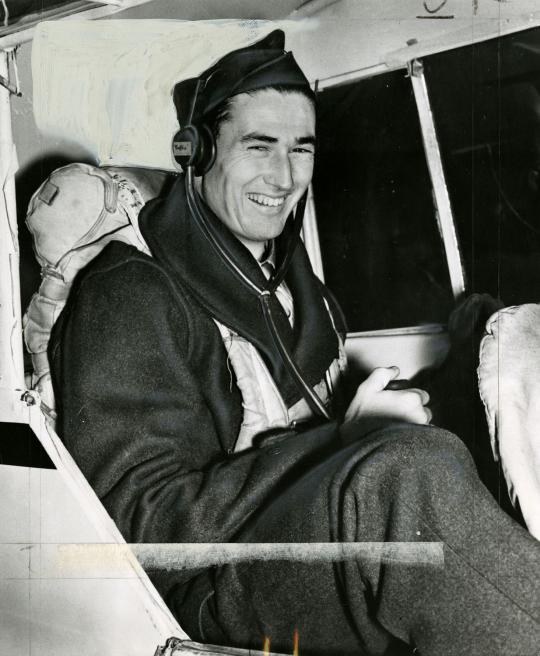

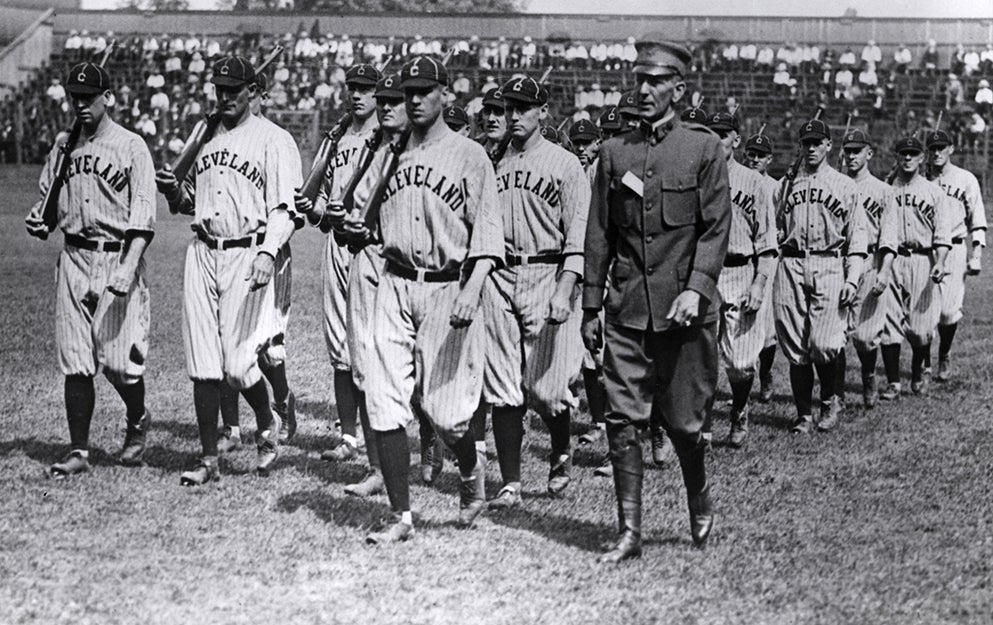

When Ted Williams was called to serve in the Korean War, he hadn't flown a military plane in seven years. Accustomed to flying F4U Corsairs from World War II, he quickly learned how to fly F9F Panther jets. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Regardless of whether Americans were paying attention to it or not, the Korean War continued to rage on throughout the early 1950s, as an attempt to squash a communist threat overseas. The infectious wave of patriotism that had inspired so many young men and women to volunteer during World War II was decidedly absent this go-around, so Congress passed the Selective Service Extension Act, requiring all active military and reservists to head back into combat.

That’s where Williams came in.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

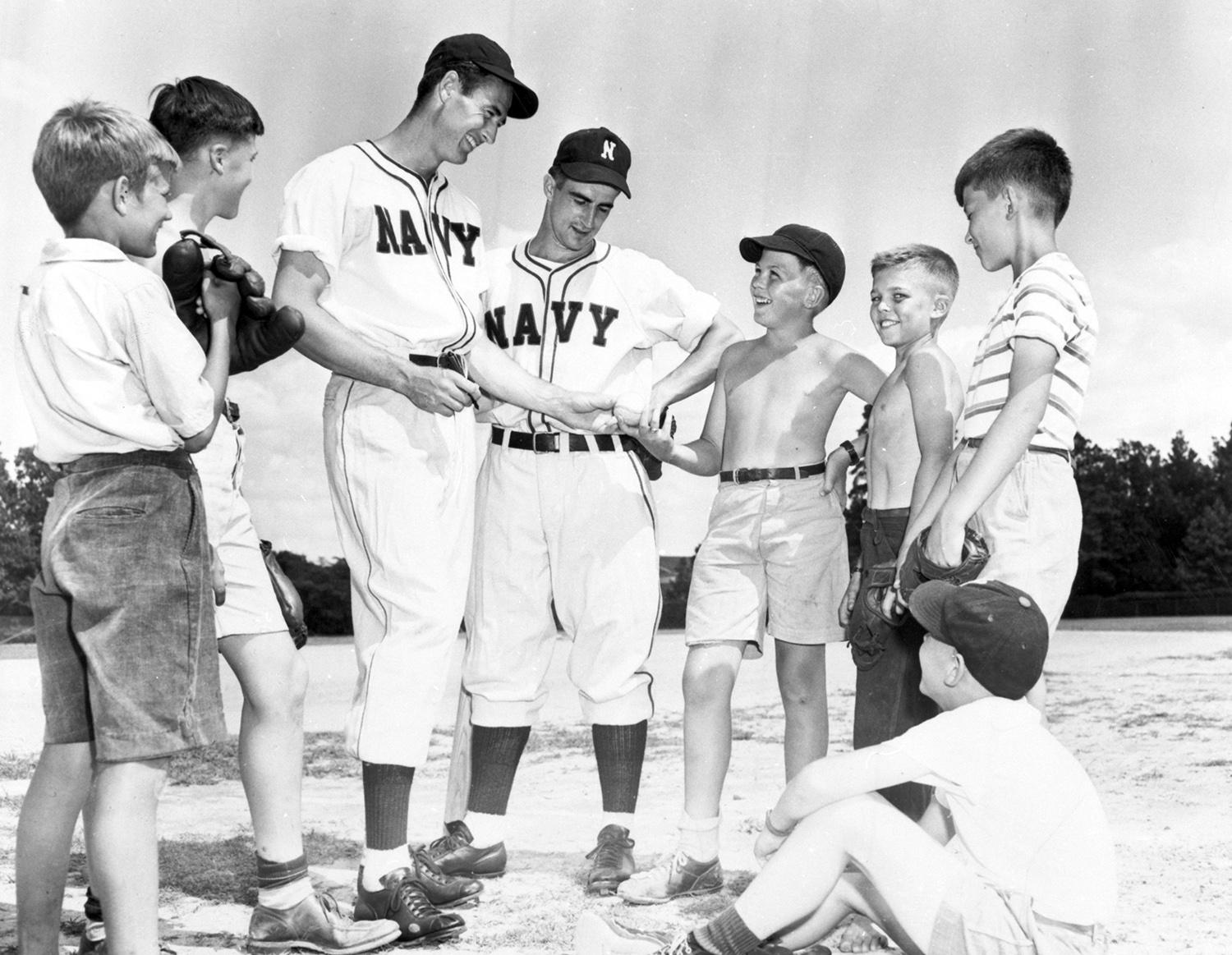

Serving in World War II from 1942-1946, he went to flight school, choosing to prepare himself for combat rather than play on a service baseball team like many other major leaguers did at the time. He was part of only 10 percent of Navy fliers to earn their wings, graduated at the top of his class and even set a student gunnery record for aerial fire while stationed at Pensacola Naval Air Base. So when he was offered the chance to discharge, he declined.

“When the fellows were getting out after the first war, they had us sign up for the inactive reserve,” Williams said to the Boston Globe. “That way you held your status as a commissioned officer. I had worked hard to get mine. If we ever went to war again, I wouldn’t have wanted to go through that again. So I signed up, never thinking we’d be in war again.”

Unfortunately for Williams, the Korean War caught him right in the prime years of his career. But with college students exempt from the draft and many career enlisted pilots serving as instructors, the call came to him – as well as to 1,100 other senior lieutenants and captains.

“He was what I call a reluctant warrior,” said Tom Ross, who flew fighter jets with Williams in the Korean War to the Boston Herald. “Flying was something he was doing because he had to. He was a guy who was caught up in the times and thrown into it. But he did his duty and he didn’t make a big deal out of it.”

So Williams treated it the same way he would handle any other situation – put his head down, and got to work. He went to Spring Training with the Red Sox, but was to report for a physical examination on April 2. After passing the test, he played the first six games of that season, but then was abruptly whisked off to Willow Grove for a refresher course on flying jets. He hadn’t flown a plane in 7 years.

Needless to say, some people had their doubts.

“What’re they going to do with Williams? Have him play baseball? Flying’s completely changed since he was in,” a naval reserve officer said to the Boston Herald. “At 800 MPH now, it’s no game for old men of 33. On the ground he’s not better than any bookkeeper or truck driver. So what does that make his principal value? The answer is headlines.”

But the Splendid Splinter was as meticulous in his preparation for a flight as he was before a game. Though he didn’t have the college degree that many of his fellow pilots had, he had the determination, and worked twice as hard to keep up with the complicated math and physics courses the fliers were required to take.

“He mastered intricate problems in 15 minutes that took the average cadet an hour,” said his Red Sox teammate Johnny Pesky, who took flight courses with Williams during World War II.

After his refresher course, Ted was stationed at the Marine Corps Air Station in Cherry Point, N.C., to learn how to fly the jet he would use in combat: the Grumman F9F Panther. Shortly after that, he arrived in Korea, on Feb. 4, 1953 as a member of VMF-311, Marine Aircraft Group 33. The Kid would remain there for five months, taking part in 39 missions while being hit three times in combat.

“He didn’t shirk his duty at all. He got in there and dug ‘em out like everybody else,” said John Glenn, a former NASA astronaut and a fellow Marine in the same squadron as Williams. “He never mentioned baseball unless someone else brought it up. He was there to do a job. We all were. He was just one of the guys.”

The slugger’s time in Korea kicked off with a bang, literally. Two weeks after he arrived, on Feb. 16, 1953, Williams flew his first combat mission, a 35-plane air strike targeting a tank-and-infantry school in Kyomipo. He was chosen to be the wingman for Major Marvin Hollenbeck, trailing his jet as they dropped 250-pound bombs from just 1,000 feet high.

“We were after a heavy target that day,” Hollenbeck recalled in an interview with Ben Bradlee Jr., author of The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams. “We had to dive, and came off the target to go directly west to a river, then due south, climbing toward Seoul and the base. I said, ‘Ted, this is your first mission. I don’t care if you hit the target or not. I just want you to be safe.’”

Unfortunately, Ted’s first mission would also be his most dangerous. As the bombs dropped toward Kyomipo, Williams lost sight of Hollenbeck in the haze and smoke. He didn’t immediately realize it, but his plane was trailing fire; he’d either been hit by the enemy or by the explosion from the bomb he had just dropped. As the plane began to sputter fluid, the emergency lights on his panel lit up like a Christmas tree. His call radio was out, and he was quickly running out of options.

“Why a wing didn’t go was just an act of God,” Ted recalled in My Turn at Bat. “The plane was still together and flying but I knew something bad was happening. Hawkins saved my life; he got me back to the base.”

Larry Hawkins was the 22-year old leader of the two-plane section in Hollenbeck’s division.

“I moved up on Williams on his starboard wing,” Hawkins said to Bradlee Jr. in 2004. “He never did look right and see me. I wanted him to eject and save his life, because his landing gear was not down, but I still couldn’t grab his attention. The tower called and said, ‘Your landing gear is not down, your landing gear is not down!’ But of course Ted couldn’t hear because his radio was off.”

“We kept talking by hand signals. He kept signaling he was getting lower and lower on fuel. I knew if I started to slow down, fuel would pool and he’d break into fire. He came in doing about two hundred knots. I was flying about a hundred and fifty feet over him off to the side.”

As he got closer and closer to the tarmac, Ted attempted to prepare for landing by opening his wheel wells, but his landing gear failed to go down and lock because his hydraulics were broken. Opening the well doors only made things worse, as oxygen rushed in to fuel the growing fire.

“I hit flush and skidded up the runway, really fast,” Williams said. “No dive breaks, no flaps, nothing to slow the plane. For more than a mile I skidded, ripping and tearing up the runway, sparks flying. I could see the fire truck, and I pressed the brakes so hard I almost broke my ankle. I always get mad when I’m scared, and I was praying and yelling at the same time. Further up the runway the plane started sliding toward a second fire truck, and the truck tried to get out of the way, dust flying behind it. I stopped right at the end of the runway. The canopy wouldn’t open at first, then I hit the emergency ejector … Boy I just dove out, and kind of somersaulted and I took my helmet and slammed it on the ground, I was so mad.”

Amazingly enough, Williams survived the accident without a scratch – his only injury was a sprained ankle, from pushing down on the break too hard. That air strike was the largest of the year, as 369 bombs dropped, destroying 96 buildings. Many wondered why Williams didn’t eject out of the cockpit, but the future Hall of Famer saw not only his life on the line, but the future of his career at stake.

“It was the only real fear I had flying a plane, that if I had to bail out I wouldn’t make it,” he said. “I thought I’d surely leave my kneecaps in there. I’d have rather died than never to have been able to play baseball again.”

Ted would be back on the job less than 24-hours later, unloading six bombs in an attack just south of Pyongyang on Feb. 17. He would fly 38 more missions after his first, one third of which over enemy lines. But after five months in Korea, three near death experiences and almost two entire baseball seasons missed, the Marines decided to send him home on an ear and nose ailment.

“My ear trouble began as soon as I got to Korea,” Ted told the press when he arrived at Barbers Point Naval Air Station in Honolulu on July 7. “I came down with colds and then pneumonia and the ear trouble developed. We have to fly high. It was one continual session in the infirmary. I guess my hearing is impaired and that may improve things as far as those left field bleachers are concerned.”

Luckily, he didn’t need to hear the ball to hit the ball, and with his 20-10 vision still intact, he was quickly back on the playing field. But because he needed an official discharge, the first couple of weeks Williams spent stateside were as a fan rather than as a player. Either way, he was just happy to be around the game.

“If I can make it, I’d like to see that All-star Game,” he said to the Boston Herald. “Do you think you could get me a ticket? Who’s hot this year anyway, Rosen, Berra, Mantle, I suppose. Any new guys around who can hit?”

Ford C. Frick quickly extended Williams an invitation to the Game, reserving a spot for him on the American League bench as an “honorary member of the team.” He received a standing ovation that lasted several minutes, and then threw the first pitch to Roy Campanella.

“He would have been a handsome figure of a man in his Marine uniform, with ribbons on his chest,” White Sox GM Frank Lane said to the Christian Science Monitor. “But he came out to Crosley Field in civilian clothes – sport coat – just as he has always dressed. I couldn’t help thinking … how much I admired him for coming that way. None of that hero stuff for him.”

On July 23, Williams was officially released from duty. The war came to a close a couple of days later, on July 27, 1953. Just two days later he signed his contract for the remainder of the 1953 season, with only 37 games to go. It didn’t take very long for him to get back into the swing of things.

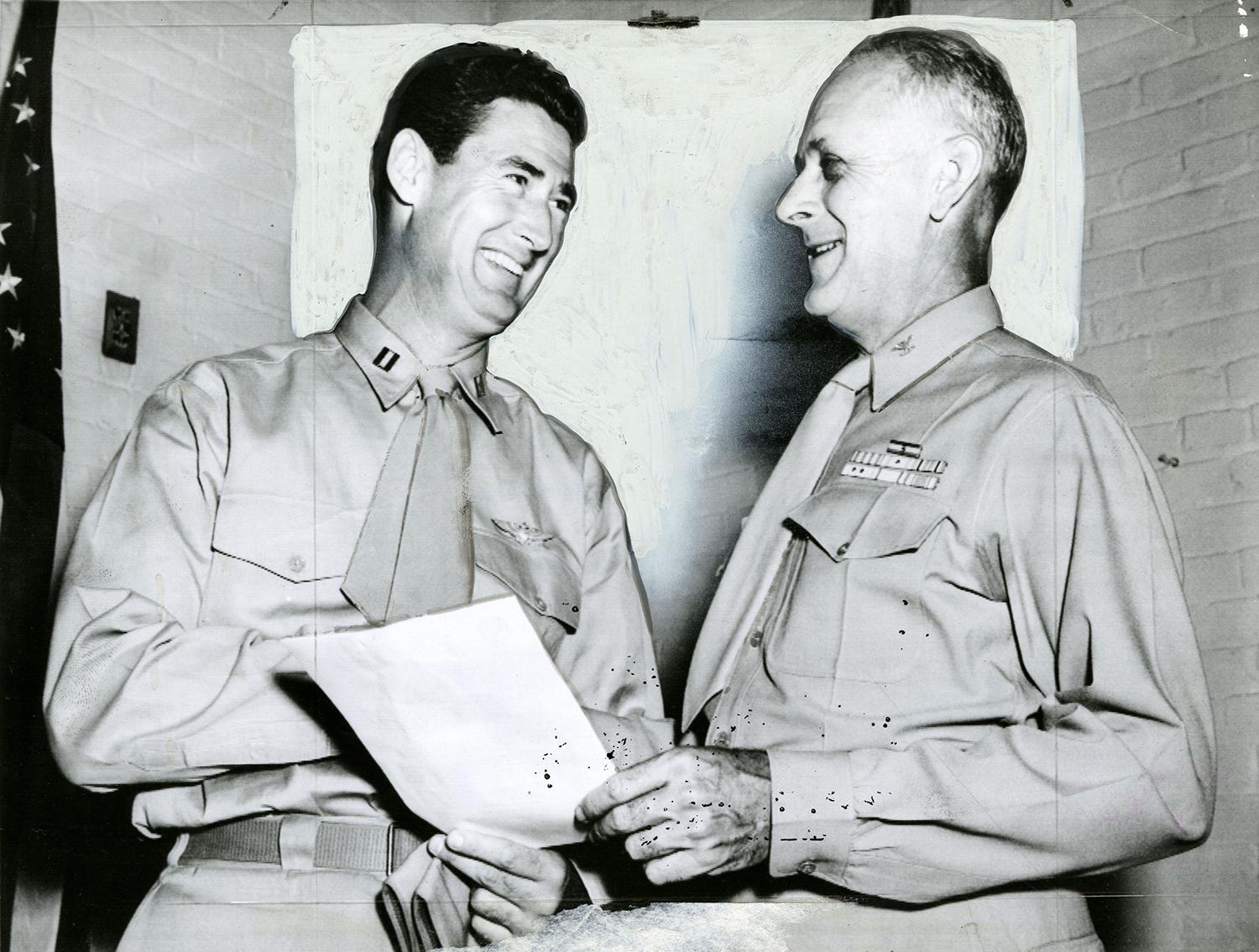

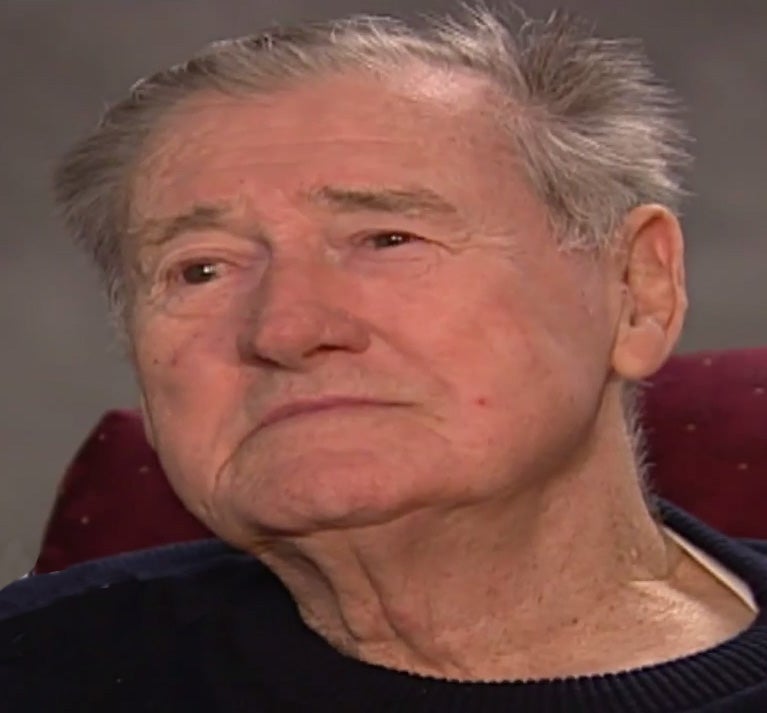

Yankees infielder Jerry Coleman (left) served alongside Ted Williams in the Korean War, and was the only professional baseball player to serve in combat in both World War II and Korea. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

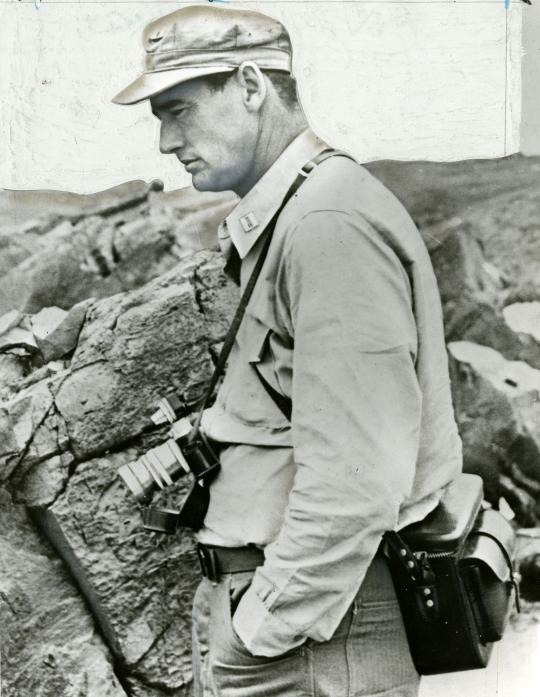

An image of Ted Williams during his training to be a jet pilot, in Roosevelt Roads Naval Base, Puerto Rico. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

In his second appearance back for the Red Sox, he hit a 400-foot home run that excited fans so much, that one newspaper reported they disregarded the fact that the team had lost the game, 9-3. The last home run he had hit was on April 30, 1952 – his final game before leaving for Korea. For 110 plate appearances in 1953, The Kid averaged .407 and had a slugging percentage of .901. He was hitting nearly one home run every seven times at bat, causing many to wonder what his numbers would be like if he hadn’t lost so many seasons to service in the military.

But Williams, who would play for seven more full seasons and then be inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1966, looked back at those years with pride.

“I know how lucky I've been in life, more than anybody will ever know,” he said in an interview at the Hall of Fame in 2000. “I've lived a kind of precarious life style, precarious in sports, flying and baseball. I worked hard (at flying). I wasn't prepared to go into it. Then I had to work as hard as hell to try to keep going, to try and keep up. I think that's as great an accomplishment as I did in my life. The other thing, of course, is that I had a good baseball career.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame