- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Remembering the Senior Professional Baseball Association

#GoingDeep: Remembering the Senior Professional Baseball Association

They were all former ballplayers who had varying degrees of success on a big league diamond.

In the late 1980s, these Old Boys of Summer were given – though the moment was fleeting – the rare opportunity to exhibit their finely honed baseball skills as part of a team once more.

Familiar faces from the 1970s and ‘80s – some recently active, others away from the game for a number of years – were once again toeing the rubber and strolling to the batter’s box. A sampling of the talent ran the gamut from 1971 American League MVP and Cy Young Award winner Vida Blue to accomplished closer Al “The Mad Hungarian” Hrabosky, southpaw slinger Bill “Spaceman” Lee to four-time All-Star infielder Toby Harrah, and Al Cowens, the starting right fielder on a trio of Kansas City Royals postseason teams of the mid-1970s, to Rafael Landestoy, a utility infielder for three teams over eight seasons.

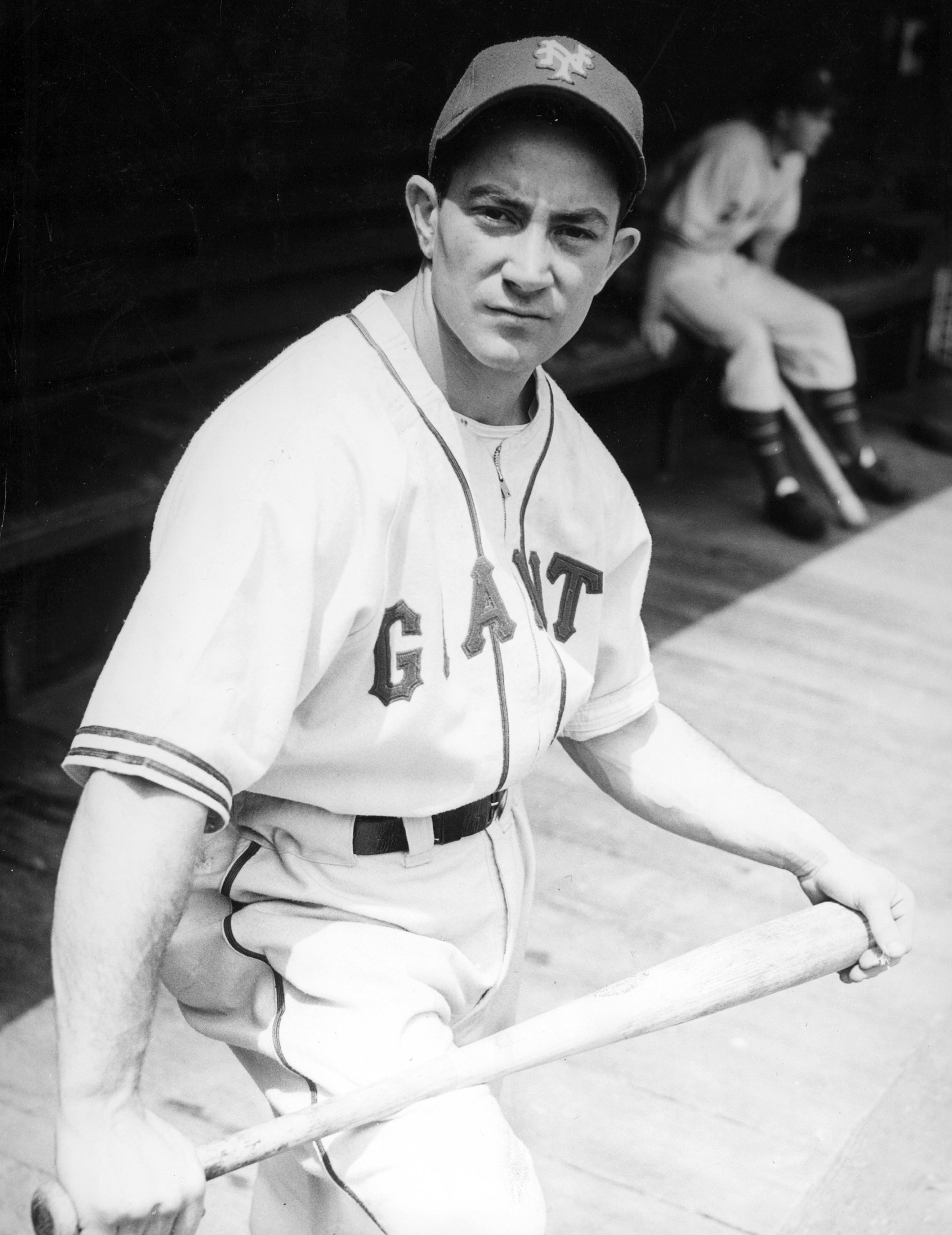

The Senior Professional Baseball Association was the brainchild of Jim Morley, a Colorado real estate developer and former minor league outfielder with the San Francisco Giants’ Class A California League affiliate in Fresno for one season in 1979.

Ten years later, in January 1989, he was in Australia at the same time a senior golf tournament was taking place nearby. If golf fans would watch these heroes from the past, the 32-year-old Morley thought, maybe there should be a senior league for baseball players. The Senior PGA Tour, as it was first known in the late 1970s, consisted of famed golfers aged 50 and older like Arnold Palmer and Chi Chi Rodriguez and was an immediate hit with fans. The senior tour, today called the PGA Champions Tour, remains a successful venture.

Amazingly, the fledgling SPBA was in operation 10 months after Morley’s brainstorm.

“It’s pretty much like anything I do, even in real estate,” said Morley at the time. “It’s like a dog that catches the postman and grabs a hold of the leg and shakes it ‘til it’s done.”

Everyone was not convinced, however.

“Isn’t this the height of absurdity? The collecting and nostalgia craze is one thing, but why should people pay top dollar to watch faded players in a regular league?” wrote Moss Klein in the March 27, 1989, issue of the Sporting News. “Old-timers’ days are nice once in a while, but this is too much. At least at oldies concerts, all the performers have to do is sing. Watching out-of-shape former baseball stars play on a regular basis would be sad. And paying to see them regularly would be downright dumb.”

After procuring the names and addresses of players who fit the loosely defined age criteria he was looking for, Morley mailed them letters that gauged their interest. The response was overwhelmingly positive.

The initial plan called for a 72-game season over three months beginning in November with teams made up almost exclusively of former big leaguers with a minimum age of 35 (32 for catchers). Salaries would start at $5,000 with a maximum of $15,000. After debating between Florida and Arizona as the upstart league’s home state, the choice was the Sunshine State due to, in part, the desirable weather, the influx of tourists that time of year and the close proximity between ballparks.

“You aren’t going to get ex-major leaguers to travel four or five hours by bus,” Morley said.

Prior to the start of the SPBA’s initial season, a price was set for franchise ownership at $850,000.

“There aren’t enough clubs out there. And which would you rather own, a Class A team of 19- and 20-year-old no-name kids or a team of ex-major-leaguers?” Morley said. “An owner has the potential to make money Year One. Even if he loses he’s not going to lose much money.”

Morley’s initial hope was that much like the senior golf tour, name recognition would be one of the SPBA’s strongest assets.

“These guys were world-class athletes and if they’ve lost a step it’s different from the guy down at the Y losing a step,” said Morley. “Over time it could very well be that it becomes the natural progression, you play in the minors, you play in the majors and you play in the seniors.”

Unfortunately, Morley’s dream scenario for the senior baseball league would be dissolved in less than two seasons due to mismanagement, unfulfilled expectations, infighting among ownership groups and financial hardships.

The league began its inaugural season in November 1989 in eight Florida cities: West Palm Beach Tropics, St. Lucie Legends, Orlando Juice, Winter Haven Super Sox, St. Petersburg Pelicans, Fort Myers Sun Sox, Gold Coast Suns (Pompano Beach) and Bradenton Explorers. And reports were that there was high interest among former big leaguers for the approximately 200 jobs available.

“The thing about it that appeals to me is that it’s a chance to play baseball again and make some money,” said longtime first baseman Mike Hargrove, who ended his playing career in 1985. “I think people would love the chance to go out and watch Hall of Famers and future Hall of Famers play.”

“We’re not talking about 162 games. As long as it’s retired players going against retired players, it will be all right.”

Tom House, the Texas Rangers pitching coach at the time, was more skeptical.

“Can [Vida Blue] throw 86 miles an hour for two starts a week, throwing 150 pitches? If he can, he should still be in baseball,” House said. “You’d have to have 25 guys on a pitching staff just to get through a week. The concept looks good on paper, but there are provisions they haven’t considered.”

There was even wild speculation that future Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt, who had just retired from the Philadelphia Phillies in May 1989, would join the SPBA only a few months later, a report his lawyer “unequivocally” refuted.

“I know Mike better than anyone and I know he will not be playing,” said Schmidt’s attorney, Arthur Rosenberg. “That’s crazy. He just walked away from a million-and-a-half dollars guaranteed to him by the Phillies. All he had to do was just show up. But Mike was dissatisfied with his play.”

Chicago Cubs broadcaster Steve Stone, who captured the 1980 American League Cy Young Award after a 25-win season with the Baltimore Orioles, jokingly denied any interest in the newfangled old-timers league.

“What is the salary?” he asked. “I can make that much going to lunch and making a speech.”

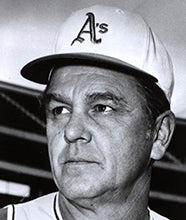

While the Gulf Coast Suns named longtime Orioles manager Earl Weaver as their skipper, another O’s legend and fellow future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer considered the opportunity but ultimately decided against giving the game another shot with the SPBA.

“(The league) should be very enjoyable,” said Weaver, who resigned after the 1986 season with a 1,480-1,060 record during his 17 years as manager of the Orioles. “It’s something people are going to like.

“The golf courses are crowded during those months, but (the league) is an interesting concept. Even if I don’t manage, I’ll still go to a number of games.”

Palmer won 20 games eight times and earned three Cy Young Awards during his career with the Orioles from 1965 to 1984.

“I don’t need to do it,” said Palmer, a year away from his 1990 election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, when contemplating pitching again. “The big thing when I retired was my arm. But I needed knee surgery. I would look at it as enjoyment. I don’t know how my body will respond.”

Even towering flamethrower J.R. Richard, whose 1980 stroke at the age of 30 ended a stellar career, signed with the Orlando Juice to give the sport another shot.

“I’ve been working out regularly and have no after-effects from the stroke,” said the 39-year-old Richard, who spent his entire 10-year career with the Astros compiling a 107-71 record with 1,493 strikeouts. “I’m looking forward to playing in this league. I think people will be surprised with what a lot of the players can still do.”

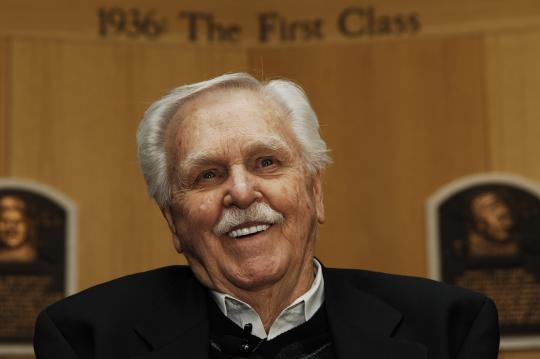

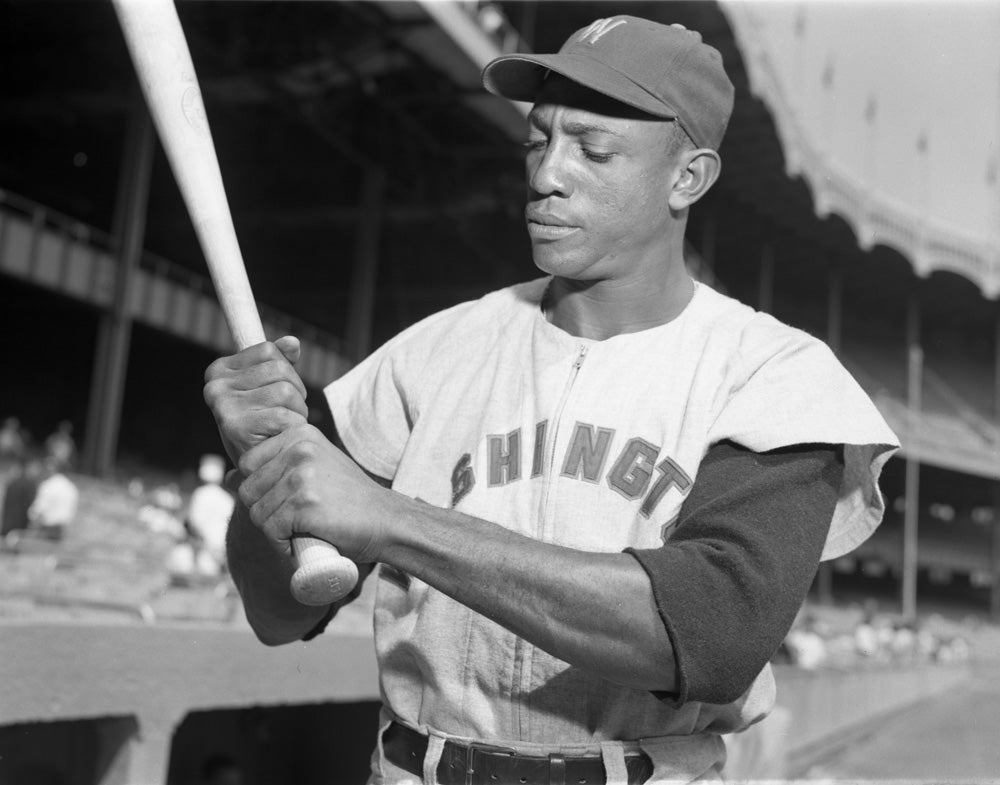

Mere weeks from his opening slate of games on Nov. 1, 1989 – and with former All-Star center fielder Curt Flood named commissioner – Morley’s public enthusiasm for this new sports venture was still at a fever pitch despite the naysayers who pointed to the recent failures of the United States Football League, the World Football League and the North American Soccer League.

“I think the league will fly,” Morley said. “I don’t think there’s any danger because all the owners have budgeted enough money and put enough money aside so the league will succeed. There’s a very real possibility after year one that a team might move from a city. Or maybe an ownership group would drop out and another ownership would take over. Just the natural attrition that takes place in all businesses.

“In our league, each team will probably have 10 or 12 name players. (Fans) will be able to get close to them. The fans are coming out to see the players. They’re not coming out to see the stadium. They’re not coming out to see the owners.”

Journeyman utility infielder Bill Stein, a 14-year big league veteran with four teams who hadn’t played since 1985, had a simple reason for giving the game another shot with the SPBA.

“I’m coming back mainly because it’s fun to play,” said the 42-year-old Stein, a minor league coach with the Mets at the time. “When you play as long as I did, it stays in your blood…I’m also was glad to see that Nolan Ryan signed and will be in Texas next year.

“I think this has the possibility of really being something if it is handled properly. I think people in their late 20s, 30s and early 40s will recognize the names if they are baseball fans.”

The senior league got underway – tickets costing between $4 and $10 – with team’s rosters limited to 24 players with a salary cap of $550,000. A total of 192 players – seven with no major-league experience – signed to play in the league. Reports had the average age of the players as 38.78, an average of 9.31 years of major-league experience and had been out of baseball for 5.21 years.

While word from league officials was they needed to average 2,500-3,000 fans a game to break even, the opening day crowds were 3,304 at West Palm Beach, 2,302 at Fort Myers, 1,428 at Winter Haven and 1,242 at Orlando. The following day, those figures dipped to 638 at West Palm Beach, 1,083 at Fort Myers, 324 at Winter Haven and 512 at Orlando.

One year after ending his big league managerial career with Seattle, Dick Williams was again in the dugout leading the West Palm Beach Tropics. Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2008, Williams 21 seasons spent with the Red Sox, A’s, Angels, Expos, Padres and Mariners ended with a record of 1,571-1,451.

“I don’t need the visibility,” said Williams, who managed in four World Series. “I’m not interested in managing in the big leagues. I’m sure Earl [Weaver] feels the same way.

“This is fun. Managing in the big leagues has become a glorified baby-sitting job. Management pays so-called stars ridiculous amounts of money and then pampers them so much the manager’s hands are tied. Managing in this league, there is none of that BS. There are no agents to deal with and no prima donnas.”

Rollie Fingers, a closer who won World Series titles with the A’s under Williams in 1972 and ‘73 and was now reunited with his fellow future Hall of Famer with the Tropics, had faith in this new endeavor: “It’s going to work. The fans come down here for the season. What better chance to see some guys play who they grew up with.”

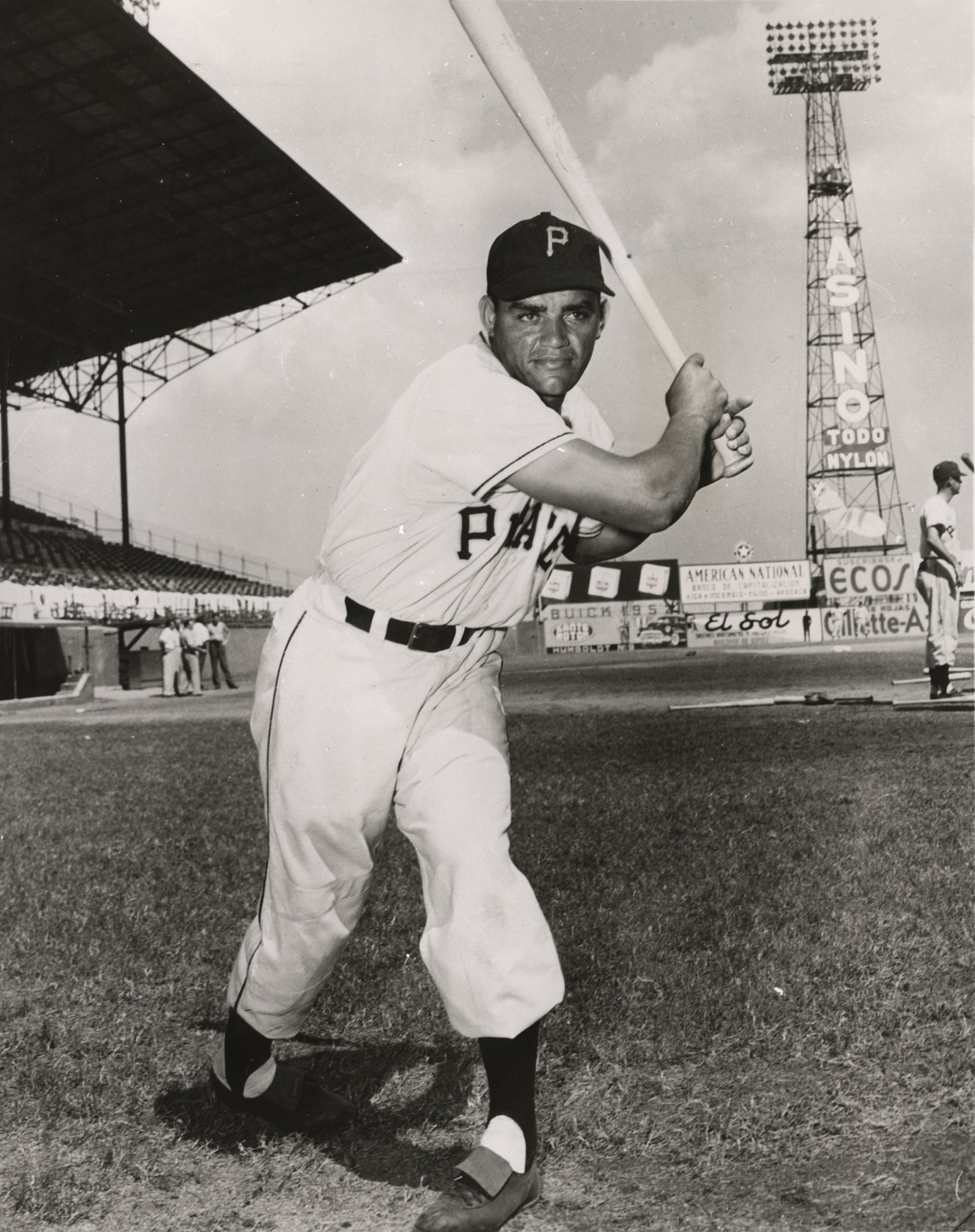

For Fort Myers Sun Sox outfielder Amos Otis, a five-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove Award during his time with the Royals in the 1970s, this was a chance at redemption.

“My last year in the majors was disastrous,” said Otis, who ended his career batting .165 in 40 games with the Pirates in 1984. “Now this league comes along and it’s an opportunity to go out on top. I want to be remembered as a good player, not as a broken-down guy.”

Bill Lee, a pitcher with the Winter Haven Super Sox, joked early in that first season: “We have a few guys with good arms, but they have bad legs. We have a few guys with good legs, but they have no arms. If we could put three or four guys together, maybe we could come up with a complete player.

“There’s nobody here who thinks he can get back to the big leagues. At least I hope there isn’t because they’re in for a disappointment.”

While some observers claimed the players they knew now looked like they were moving in slow motion, owners around the league tried to put a happy face on the slow gate returns.

“You can make money,” said Don Sider, a co-owner of the West Palm Tropics. “You’ll lose the first year but you can make money, certainly. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be in it. If we’re here next year, we’ll have corporate sponsorship and TV contracts. With those things going, we can make money and pay the players a little more, improve the setup and make money.”

Russell Berrie, owner of the Gold Coast Suns, imagined his involvement as “a successful hobby,” adding “Anything you do you like to be successful, but I’m not in this to make money. We all have our field of dreams and this is mine. I’m out to enjoy myself, have fun, and develop something. Some years down the line we can look back and say, ‘Hey, we started that.’”

An infamous transaction that first SPBA season made news across the country when the Gold Coast Suns acquired the ageless hurler Luis Tiant from the Winter Haven Super Sox for 500 teddy bears that were later distributed to children attending a game later that season. The trade was made to facilitate “El Tiante” request to remain in Miami and pitch for the Suns.

“They didn’t have any player we needed who they were willing to trade,” Super Sox owner Mitchell Maxwell said. “We wanted to get something positive back for Luis.

“They won’t be cheap teddy bears. They’re going to be nice big ones.”

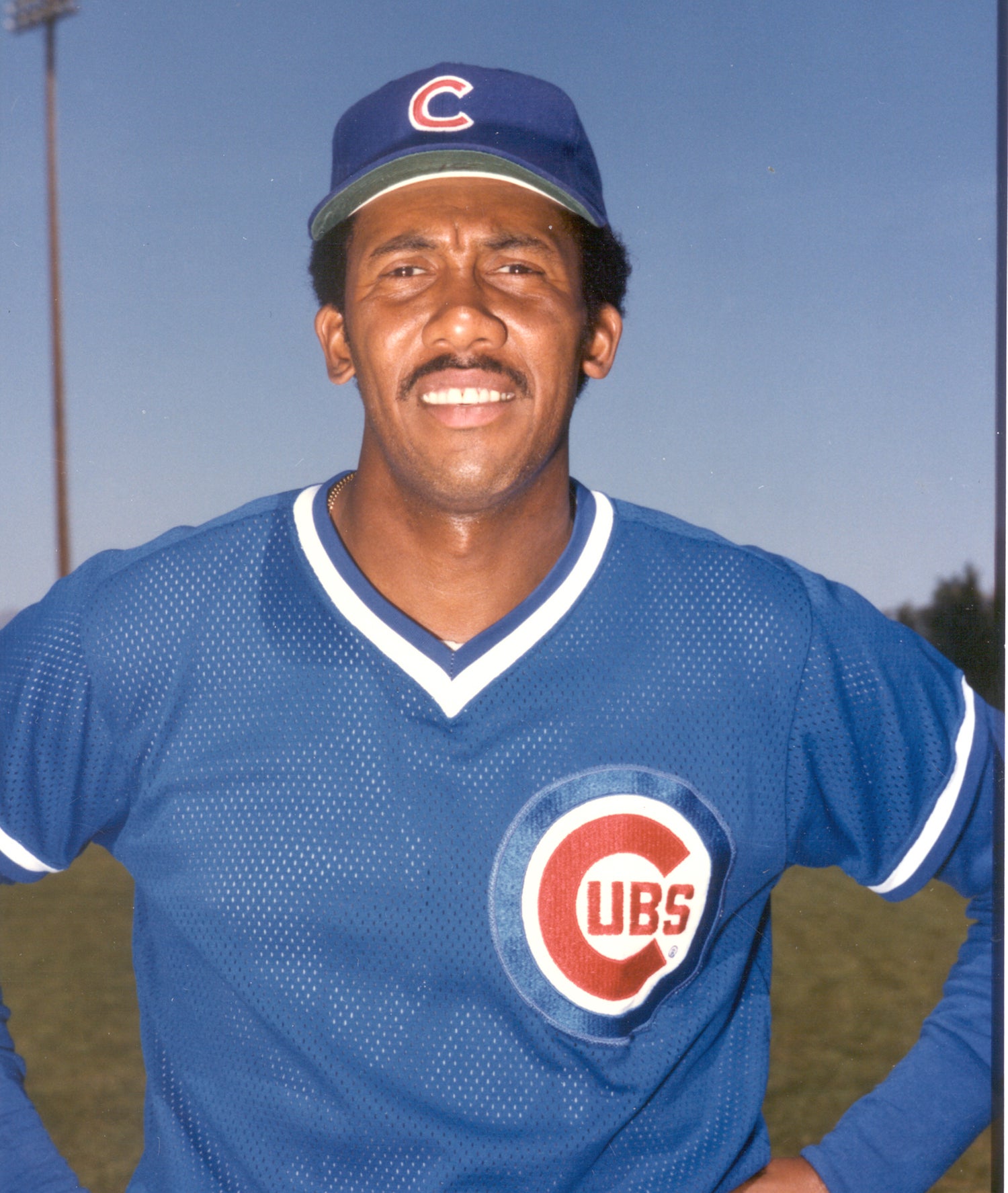

Palmer and Joe Morgan were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America in January 1990. But Cubs legend Ferguson Jenkins, who was a member of the Winter Haven Super Sox’s pitching staff, fell short on his second year on the ballot with 296 votes, needing 333 to reach the 75 percent threshold for election. The longtime righty would become a Hall of Famer in 1991.

Jenkins recalled his time with the short-lived senior baseball league.

“I was with the Winter Haven Super Sox and we had a lot of Boston players there. Bill Lee was there, Rick Wise, Cecil Cooper and Luis Tiant,” Jenkins said. “And the following year I went to the Sun City Rays that were in Sun City in Arizona. Jim Marshall was the manager and I played with Rollie Fingers and a few other talented players.

“I think that senior league would have really been successful if we’d have had some major sponsors. They really didn’t have a lot of backing. It came along at the same time as senior golf and senior golf had major sponsors. I think that’s why they were more successful than the baseball.”

The first regular season of the Senior Professional Baseball Association ended on Jan. 31, 1990, with the West Palm Beach Tropics having the best record at 52-20 while the St. Petersburg Pelicans captured the postseason title over the Tropics. Fort Myers Sun Sox Tim Ireland led the league with a .374 batting average.

Members of the SPBA first all-star team included: 1B Dan Driessen, Fort Myers; 2B Tim Ireland, Fort Myers; 3B Jim Morrison, Bradenton; SS Ron Washington, West Palm Beach; OF Steve Henderson, St. Petersburg; OF Mickey Rivers, West Palm Beach; OF Jose Cruz, Orlando; DH Amos Otis, Fort Myers; C Stan Cliburn, Bradenton; SP Juan Eichelberger, West Palm Beach; RP Rick Lysander, Bradenton.

The final average attendance figures were: West Palm Beach, 1,600; Fort Myers, 1,328; St. Petersburg, 1,132; Gold Coast, 985; Bradenton, 781; St. Lucie, 607; Winter Haven, 529; and Orlando, 400. The league average was 920 fans per game.

“And we all lost money,” said Morley, who owned the St. Petersburg Pelicans, “from about $520,000 to as much as a million.”

Bill Campbell, who ended his 15-year big-league playing career in 1987, pitched for Winter Haven and came away from that first season in the SPBA with realistic expectations on his future.

“Some of these guys came down with a fun-and-games attitude, that this was going be a party league, that they’d just throw on a glove and mess around for a couple of innings,” said Campbell. “But it never fails. Once you put on that glove, the instincts take over. No one wants to embarrass himself. Guys start working harder, like they have to prove themselves all over again.

“But it’s funny how sometimes you rationalize. I’d start popping the ball and I’d find myself thinking, ‘Maybe there’s still enough there …’”

The SPBA, which operated with eight Florida-based teams during its inaugural season in 1989-90, went westward to add expansion franchises San Bernardino (Calif.) Pride and Sun City (Ariz.) Rays for its second campaign. League officials said the additions were made, in part, to engage the many former major leaguers who lived in these states.

Possibly foreshadowing the upheaval the league would soon experience, the Florida teams from that first season that folded included ones in Gold Coast, Orlando, St. Lucie and Winter Haven, while the West Palm Beach Tropics became a traveling team known as the Florida Tropics, and the Bradenton Explorers moved and became the Daytona Beach Explorers.

The SPBA’s second season, this time with a scheduled 56-game slate that started on Nov. 23 – the day after Thanksgiving – saw the six-team league drop its minimum age to 34 (catchers at 32) and dismissed Flood as commissioner.

On Christmas night, though, Morley, shared some ominous news about a financial dispute among the ownership group of the Fort Myers Sun Sox.

“The guys in Fort Myers are a problem,” Morley said. “It may force the rest of us to suspend the season. Neither side is budging and willing to give.”

According to Morley, it would cost the Fort Myers owners about $150,000 to finish the season, which was to conclude Feb. 3. With none of the three co-owners willing to spend more money – it’s estimated they had invested between $1 million and $1.5 million already – and with the league was unwilling to bail out the franchise, these was no other choice.

A day after Christmas in 1990, the transactions listed in newspaper sports pages across the country read in small type that a much-ballyhooed new baseball league had suspended play. Unfortunately for those involved, less than halfway through its second season, the SPBA folded on Dec. 26, 1990. Only a few days prior, the players had agreed to accept a 16-percent pay cut for the season’s final month in an effort to save the league.

“The problems with Fort Myers forced them to shut down, which forces us to suspend play for the rest of the season,” said Morley, the league founder and president and owner of the St. Petersburg franchise. “I’m tremendously disappointed in the way things have turned out.

“Most of the time in this situation, the reason is financial. This isn’t financial. Fort Myers is far and away the wealthiest franchise. They have an internal partnership problem.”

Among the new players the SBPA added for its 1990-91 campaign were Jim Rice, the longtime slugger with the Red Sox whose final major league season was as a 36-year-old in 1989. The Class of 2009 Hall of Famer was batting .292 with three homers and seven RBI in 15 games with St. Petersburg when the league folded.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s collection contains three programs, one booklet and two tickets from the league which ultimately couldn’t survive with its lack of attendance – despite opening to great fanfare and attracting some of the sport’s top names back to the diamond.

“No matter how old you are, you still feel like a kid when you play this game,” said Fort Myers pitcher Eric Rasmussen. “When they take away your team, it’s sad.”

Fort Myers catcher Marty Castillo was acutely aware of the sad facts, adding: “Half the people in this town didn’t even know they had a Sun Sox baseball team. We’ve gotten more press in the last two days that we’re going to fold, more awareness through that, than we ever had.”

Todd Cruz, the St. Petersburg Pelicans shortstop was more succinct in his feelings: “I feel terrible about it because I wanted to play so bad. For a lot of us, this is the biggest thrill in our lives.”

In retrospect, Morley said his brainchild probably was rushed into existence.

“I guess a lot of people are laughing at me know,” he said. “But I don’t care what anybody says. This was a good idea and it still is. This was the best-kept secret in town. I don’t understand why people didn’t show up.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum