- Home

- Our Stories

- Lefty-throwing catchers among game’s great rarities

Lefty-throwing catchers among game’s great rarities

It was late on a Sunday afternoon in September 1988, and the Pittsburgh Pirates were waiting at the Philadelphia International Airport to board a charter flight to St. Louis following an extra-innings loss to the Phillies at Veterans Stadium.

The Pirates were in second place in the National League East but far enough behind the New York Mets that pitching coach Ray Miller, left-handed pitcher Neal Heaton and reserve first baseman/outfielder Benny Distefano were already looking ahead to the 1989 season.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

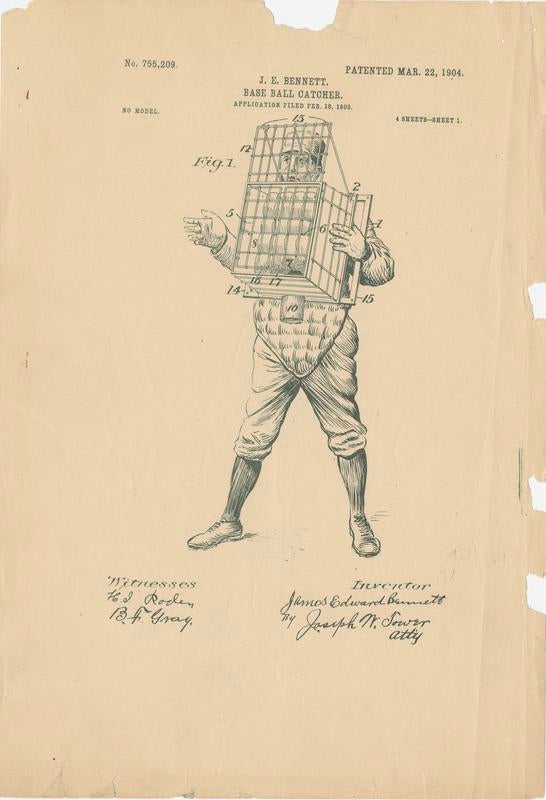

Miller, always a thinking man’s pitching coach and experimenter, wondered aloud why conventional baseball wisdom dictated that left-handed fielders could not be catchers because they were considered unable to handle pitches with movement from left-handed pitchers.

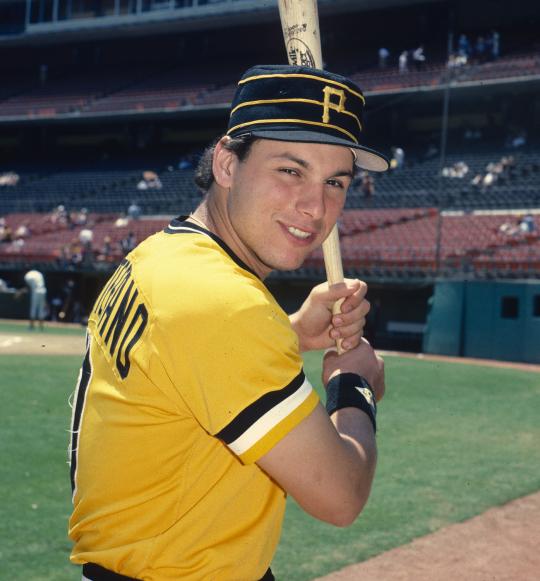

As the three kept talking about the subject, Distefano, a southpaw, said he played catcher as a kid growing up in New York and would love to try it.

On the final day of the season, Pirates manager Jim Leyland told Distefano he wanted him to report to Spring Training early the following February along with pitchers and catchers. That’s how the groundwork was laid for the last lefty to squat behind the plate in a major league game.

“I think they already had it in their minds that they wanted me to catch so it would increase my versatility and give them an emergency third catcher because the major leagues had 24-man rosters then,” Distefano said, referring to a period when MLB decided to reduce the roster limit by one player for a few years.

“I’m pretty sure Ray brought that up just to kind of see what my thoughts would be about it. I wanted to do it. I thought it would be fun, and I thought it would (increase my) chances of staying in the big leagues.”

Emergency third catchers rarely ever put on the equipment in a regular-season game, but Distefano had the feeling during Spring Training in 1989 that the Pirates were going to treat him different. He caught in parts of a number of exhibition games and a full “B” game.

Sure enough, Distefano caught three times that season for a total of six innings and acquitted himself quite well. He had only one passed ball and allowed only one stolen base while Pirates pitchers threw just one wild pitch when he was behind the plate.

“It was fun,” Distefano said. “I had a good time doing it. I just wish I could have done it more often.”

Distefano’s last appearance at the position was on Aug. 18 when he caught the last three innings of a 13-6 loss to the Braves at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. The 1989 season wound up being the last of his four seasons with the Pirates.

Distefano did not reach the major leagues again until 1992 when he had a 52-game stint with the Astros. His ability to catch was part of what made him attractive to Houston manager Art Howe during a season in which Hall of Famer Craig Biggio was moved from catcher to second baseman that spring.

However, Distefano didn’t get the chance to catch that season while sitting behind Ed Taubensee and Scott Servais on the depth chart. It turned out to be Distefano’s last year in the major leagues.

So more than a quarter of a century later, Distefano remains the answer to a trivia question.

“I didn’t think it would be this long without another left-hander doing it,” Distefano said. “It’s surprising to me.”

Distefano is one of just three left-handers to catch in the major leagues since 1905, along with Dale Long and Mike Squires.

The Hall of Fame’s collection contains four left-handed catcher’s mitts, including one from Gilbert Cooling, who played on semi-professional teams along Maryland’s Eastern Shore during the early 20th century and caught left-handed throughout his career. Cooling’s son, Charles, donated his mitt to the Hall of Fame in 1961.

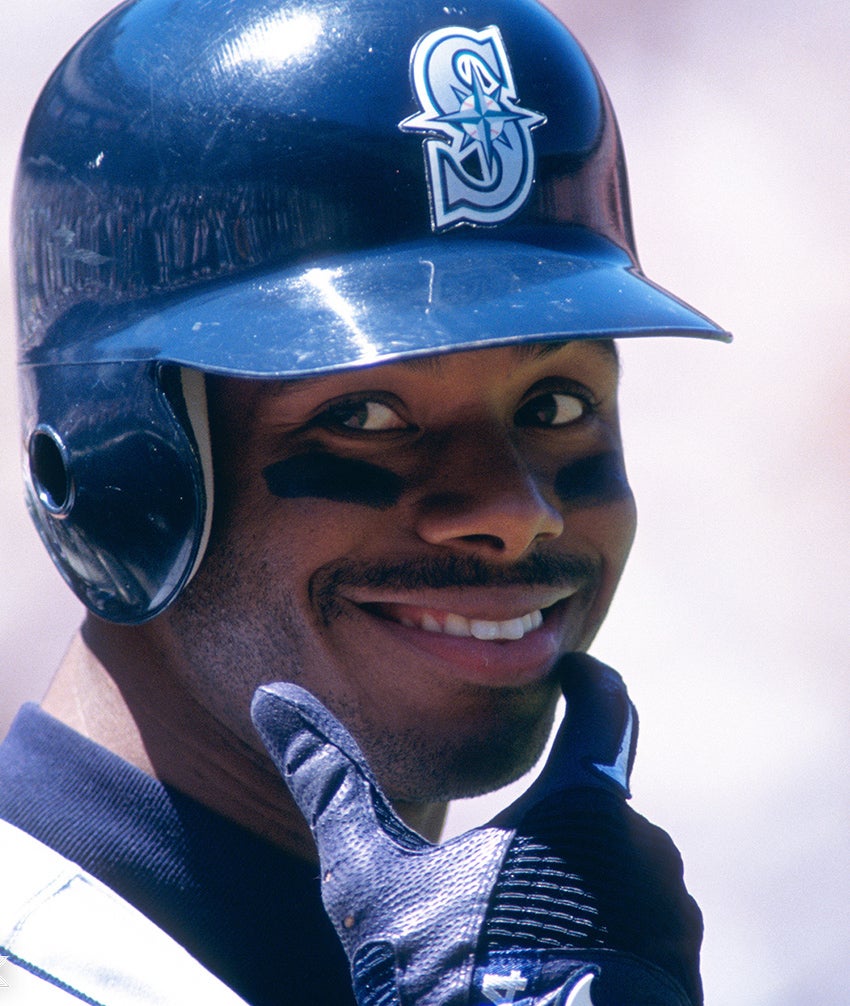

Long, primarily an outfielder, caught a total of 1 2/3 innings in two games for the Chicago Cubs in 1958. That came two seasons after his much more famous feat of setting the major league record by hitting a home run in eight consecutive games for the Pirates, a mark later matched by New York Yankees first baseman Don Mattingly in 1987 and Seattle Mariners center fielder Ken Griffey Jr. in 1993.

A left-handed catcher’s mitt used by Long is a part of the Hall of Fame’s collection.

Dale Long used this mitt, now part of the collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, when he appeared in two games as a catcher for the Cubs in 1958. Long, a lefty thrower, is one of only a handful of southpaws to appear behind the plate in big league history. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

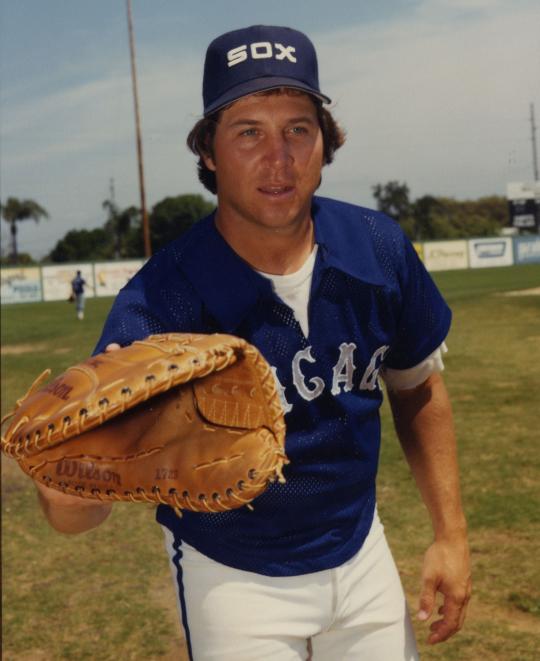

Squires had two one-inning stints as a catcher in 1980 with the Chicago White Sox. Taking into consideration Squires was an excellent defensive first baseman, Hall of Fame manager Tony La Russa thought he would be able to handle the duties of emergency catcher.

“I had good hands and that’s what really you’re looking for in a third catcher,” Squires said. “You want somebody who can go behind the plate and, more than anything, be able to catch the ball.”

The idea of Squires becoming a catcher was hatched by happenstance. He was sitting poolside with White Sox general manager Roland Hemond at the team hotel in Sarasota, Fla., during Spring Training in 1978 when Marv Foley, a left-handed hitting catcher, walked by.

Hemond remarked about how a good left-handed-hitting catcher could have a long career in the major league because they is a scarcity of them. Squires answered back that a catcher who was a left-handed fielder would be even harder to find and he would like to try it.

“Roland ordered a left-handed catching mitt and it came in the mail two days later,” Squires said.

That led to a childhood dream eventually coming true. Squires’ father had been a catcher growing up and the son wanted to follow in his footsteps only to be told by his Little League coaches that left-handers don’t play the position.

However, Squires proved that to be false at the major league level and so did Distefano. Both have distinct memories of certain moments behind the plate.

Distefano’s came in his last game as a catcher when Braves center field Oddibe McDowell stole second base. Distefano made a strong throw that likely would have nabbed the speedy McDowell. However, the throw was late because Distefano had to block a curveball in the dirt from Doug Bair.

In Squires’ first game at catcher, Hall of Famer Robin Yount came to the plate for the Milwaukee Brewers with no outs, a runner on first base and Ed Farmer pitching. Squires called for a full-count curveball and Farmer froze Yount for a called strike three.

“You should have seen the look on Robin’s face,” Squires recalled with a laugh. “I think the last thing he expected was a left-handed first baseman calling for a curveball on a 3-2 pitch.”

John Perrotto is a freelance writer from Beaver Falls, Pa.