- Home

- Our Stories

- Negro Leagues No-No’s

Negro Leagues No-No’s

Baseball — a game of records, unwritten rules and a century-and-a-half of professional history — has few occurrences as sacred as the no-hitter. While in progress, it’s not to be spoken of, nor the pitcher spoken to. Once completed, however, a no-no and its author live forever.

Hall of Famers pitching for American or National League clubs have accounted for 56 no-hitters. From the Providence Grays’ John Ward on June 17, 1880, to the Philadelphia Phillies’ Roy Halladay in Game 1 of the National League Division Series — his first career postseason appearance — on Oct. 6, 2010, these performances mark the pinnacle of dominance on a major league mound.

But not all no-hitters have received the fanfare they deserve. Five legends enshrined in Cooperstown accomplished the feat, only to have their hitless masterpieces — and their professional baseball careers as a whole — overshadowed due to the sport’s segregation.

In 2020, however, Major League Baseball announced that the Negro Leagues would be officially considered “major leagues,” deeming Josh Gibson’s home runs as legitimate as Babe Ruth’s, Satchel Paige’s strikeouts as true as Walter Johnson’s, and so on. MLB’s declaration can’t fill every gap in the records of Black baseball from 1920 to 1948. And the extent to which Negro Leagues baseball — its schedules, field regulations and the baseballs themselves, to name a few factors — differed from the American and National Leagues is impossible to measure.

Still, the Negro Leagues were major leagues. And on their journeys to Cooperstown, these five pitchers threw no-hitters while playing unique roles in the history of Black baseball.

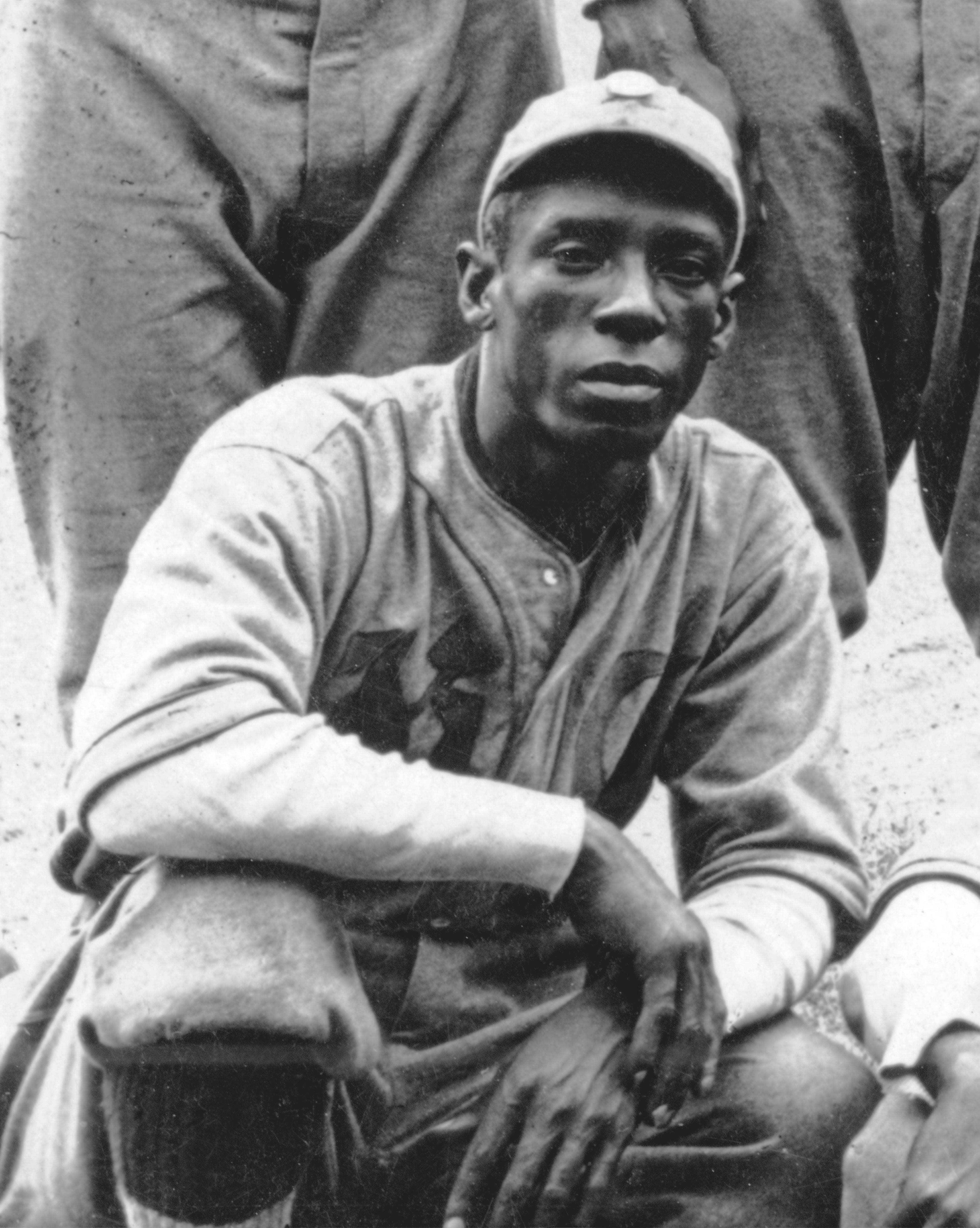

Charles Wilber Rogan, nicknamed “Bullet” for his powerful right arm, was born in Oklahoma City in 1893. His skill as both a pitcher and hitter resembled that of Ruth, who was two years younger and, of course, had the luxury of a professional league to play in starting at age 19.

Rogan had to wait a bit longer. After playing for the U.S. Army’s all-Black 25th Infantry Wreckers in Hawaii, where the Pacific Commercial Advertiser wrote he had “worlds of speed” and a “puzzling” delivery, Rogan returned to a new opportunity for elite Black ballplayers.

Throughout the 1910s, white booking agents had booked Black clubs for their ticket proceeds. In February 1920, future Hall of Famer Rube Foster, often called “The Father of Black Baseball,” founded the Negro National League, a more organized and profitable alternative to barnstorming tours. One of its eight initial clubs, the Kansas City Monarchs, gladly accepted Rogan’s services.

In 1921, his second season, Rogan led the league with a 1.72 ERA while hitting .305 with 26 extra-base hits, 19 steals and 47 RBI. The two-way star accumulated an 8.1 bWAR (baseball-reference’s measure of Wins Above Replacement) that year, more than fellow future Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston or Cristóbal Torriente.

“He was the onliest pitcher I ever knew, I ever heard of in my life,” Satchel Paige later said, “was pitching and hitting in the cleanup place.”

Rogan’s vast repertoire included his devastating palmball, a forkball and a spitball, among other offerings. Word of his pitching prowess crossed the color barrier in a time when few things could — Casey Stengel would label Rogan “one of the best, if not the best, pitcher that ever pitched.”

“Old Rogan, he was a showboat, a Pepper Martin ballplayer,” Dizzy Dean later said. “He was one of those cute guys, never wanted to give you a ball to hit.”

Indeed, on Aug. 5, 1923, Rogan gave the Milwaukee Bears absolutely nothing to hit, relieving another future Hall of Famer, José Méndez, in a combined no-no. Méndez had been a star in Cuba as early as 1907, going toe-to-toe with white American aces like Christy Mathewson and Eddie Plank in exhibition games that legitimized the island’s baseball scene. But arm issues limited his effectiveness on the mound as the 1910s progressed, and North America wouldn’t offer any true professional opportunities until the end of the decade.

Méndez, also serving as the Monarchs’ player-manager at age 38, wielded a fastball and a curveball, and he was adept at changing speeds. He retired 15 straight batters to start the second game of the Aug. 5 doubleheader before giving way to Rogan, whose four innings sealed the deal. Rogan also went 1-for-2 and scored a run in the 7-0 victory.

“Only one Milwaukee batter reached first during the second game, Rogan issuing a walk in the sixth inning,” wrote the Kansas City Times. “At no other time did one of the Bears have a chance to get on bases.”

That 1923 season was another productive one for Rogan, the hitter. As a pitcher, meanwhile, the 5-foot-7, 160-pound righty established himself as one of the greats. His 16 wins, 20 complete games, 151 strikeouts and 248.1 innings all led the Negro National League as Kansas City dethroned the three-time defending pennant winners, Foster’s Chicago American Giants.

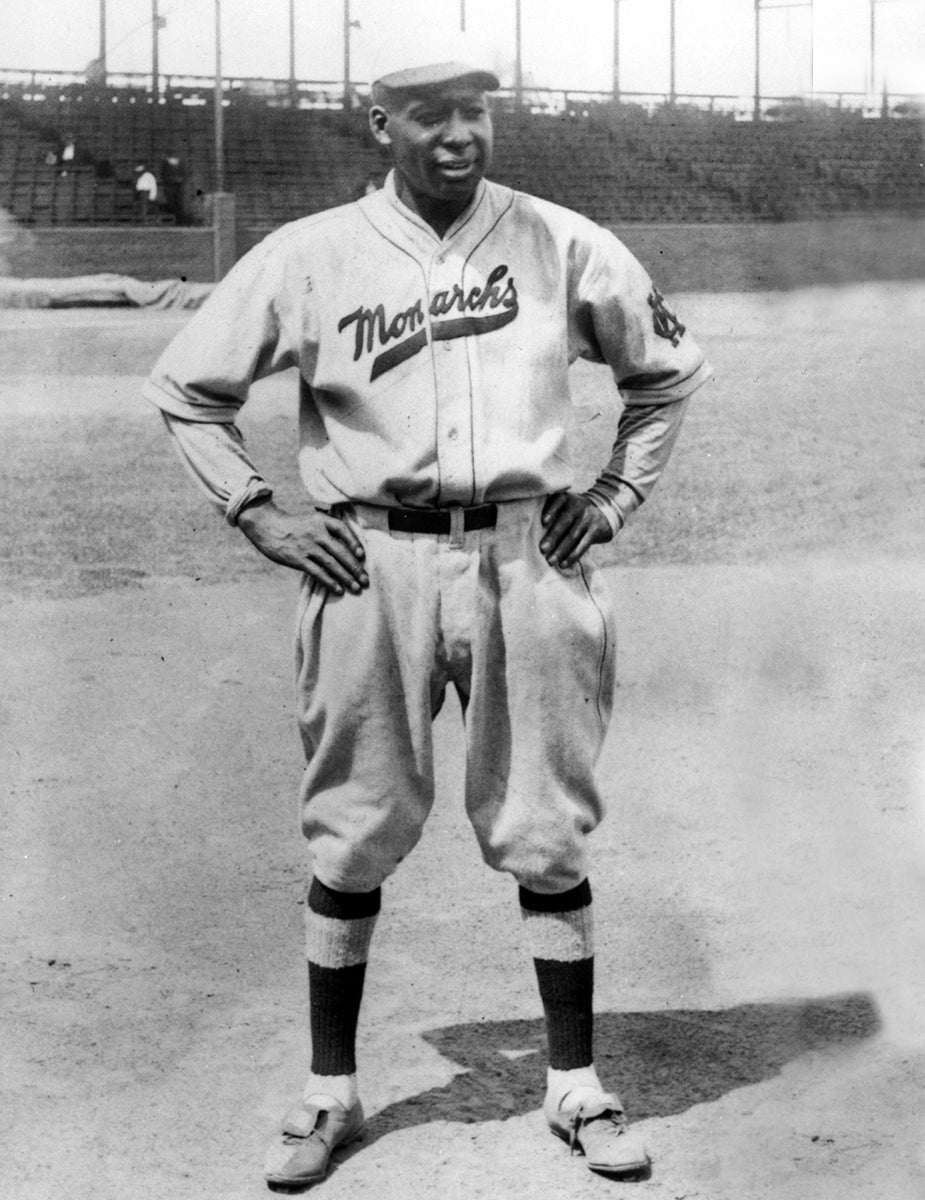

Like Rogan and Méndez, the Detroit Stars’ Andy Cooper pitched in the Negro National League from its inception. Prior to 1920, the Waco, Texas, native played for multiple semi-professional teams based in Kansas, earning the nickname “Cannon Ball Lefty Cooper” from the Wichita Beacon.

“This young southpaw is about the class of Wichita’s hurlers,” the Wichita Eagle wrote in 1919 of Cooper, then with the Wichita Colored Giants. “He has a world of stuff, speed, and a good baseball bean.”

Buck O’Neil recalled the 6-foot-2, 220-pound lefty throwing a fastball, curveball and screwball, and many spoke highly of his repertoire. But Cooper’s distinguishing trait may have been his command, which the Chicago Defender, a leading African American newspaper of the day, described as “sterling.” That combination of stuff and location proved overwhelming for the Indianapolis ABCs on June 28, 1925, when Cooper no-hit them in a complete game.

“Cooper was in rare form, pitching a no run no hit game and allowing only three men to get on base,” wrote the Defender. “Besides pitching such splendid ball, he won his own game in the fifth inning with a hot single to left, scoring Anderson Pryor from second base.”

Yes, on top of throwing a no-hitter, Cooper drove in the only run in a 1-0 win. With a career batting average below .200, he was hardly an offensive threat like Rogan, but that day, he did it all for Detroit. Cooper went 12-2 in 1925 with a 2.88 ERA, a career-best to that point.

Despite fielding two all-time greats, the Stars never finished better than third place in the Negro National League. Cooper followed eight seasons in Detroit with two in Kansas City, then returned to the Stars for another strong campaign in 1930.

Rube Foster’s creation had enjoyed a decade of popularity and success, but it depended on ticket sales to drive revenue and compensate its players. With the Great Depression in full swing, the Negro National League couldn’t continue beyond 1931. While some clubs ceased to exist, others — none more prominent than Kansas City — traveled North America on successful barnstorming tours.

In 1930, Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson invested in portable lighting and introduced night baseball five years before any white club. Night games proved popular at first and essential once the league dissolved. In the midst of the Depression, the option of nighttime baseball allowed the Monarchs to play more games across the United States and in Canada, attract more fans and stay afloat financially.

Then, in 1937, Wilkinson’s Monarchs joined the new Negro American League as a charter member. Their manager for the first four years? Andy Cooper, who also pitched a handful of games through 1939 — his age-42 season.

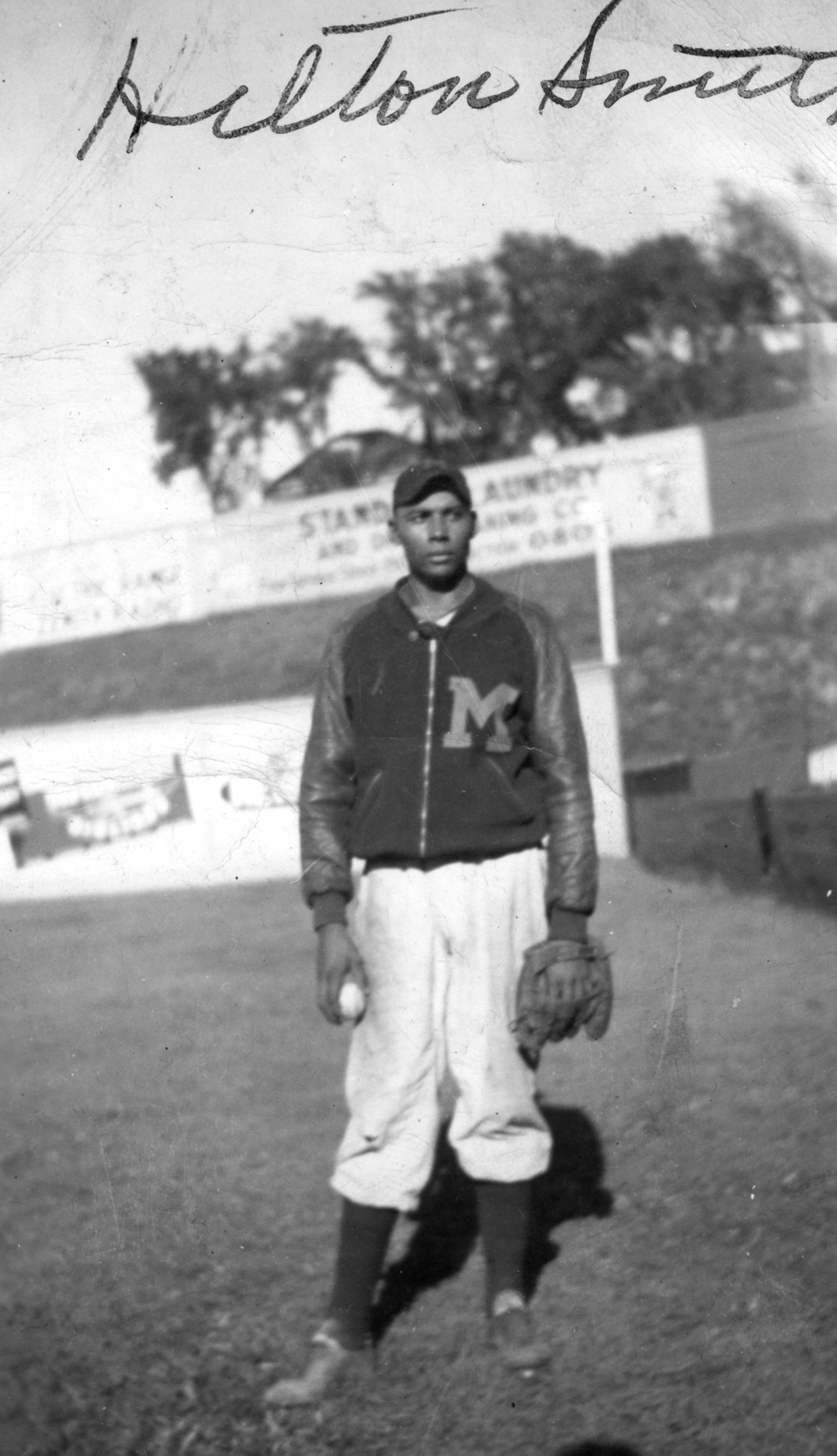

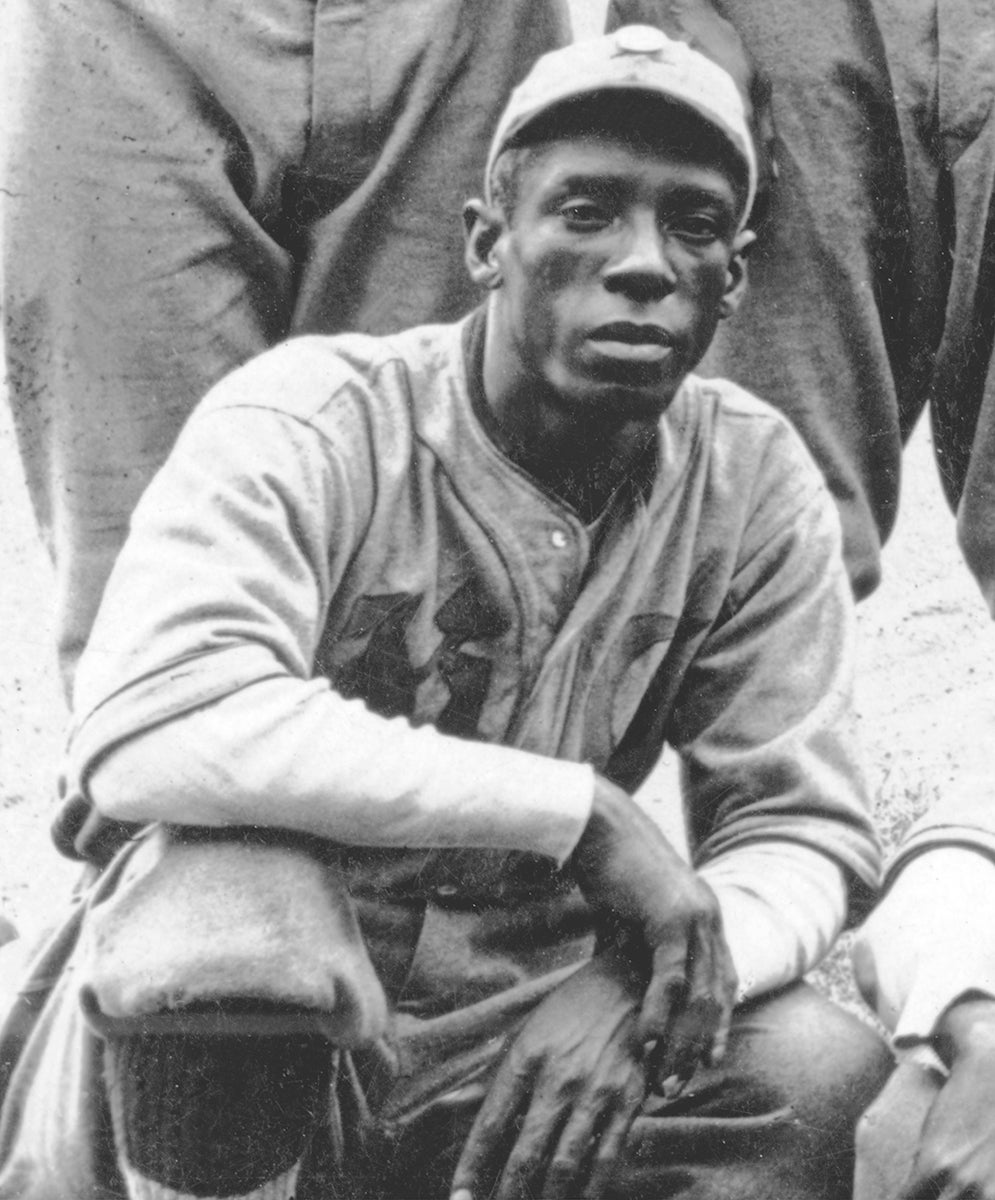

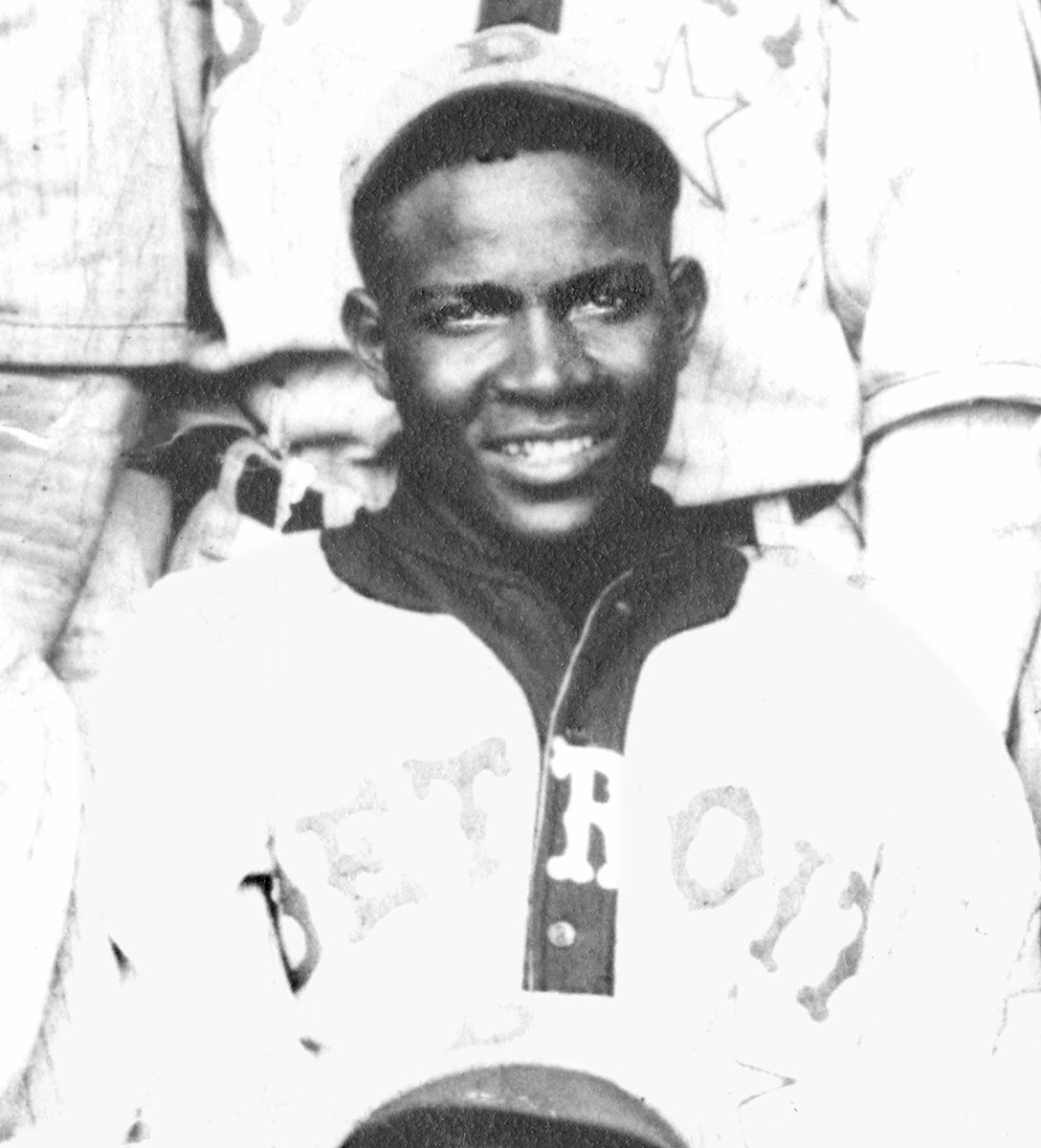

By then, a new generation of pitching talent had arrived in Black baseball, with arms like Hilton Smith bolstering Kansas City’s roster. Born in 1907 in Giddings, Texas, Smith had pitched a few seasons for the Negro Southern League’s Monroe Monarchs before that league collapsed in the mid-1930s. Then, while on tour in Bismarck, N.D., the right-hander caught Satchel Paige’s eye and joined him on the Bismarck Churchills. Owner Neil Churchill would improve his roster at any cost, so Paige helped him recruit Negro Leagues talent like Smith.

Smith’s stellar pitching for the Churchills in 1936 put him on Wilkinson’s radar and earned him a spot on the Monarchs. “When you got with the Monarchs, you were as high as you could go,” Smith said in Janet Bruce’s “The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball.”

John B. Holway detailed Smith’s emergence in “Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers.” “Actually, I didn’t learn how to pitch until I came to the Monarchs that fall,” Smith said. “I just had natural stuff before that. I learned from having such guys for teachers as Frank Duncan, Bullet Rogan and Andy Cooper.”

In May 1937, Kansas City welcomed the Monarchs back to organized ball with a parade. And on May 16, during their home-opening series, Smith no-hit the Chicago American Giants.

“‘Stringbean’ Smith, a sad Samuel hurler who moves about the field like Satchel Paige, came within a proverbial hair of twirling a perfect game to shut out the Chicago American Giants in the first of a twin bill here Sunday, 4-0,” wrote the Defender. “But while missing one [piece of history], Smith [earned] another by holding the Chicago nine to no hits and no runs and only allowing one man to reach first, Melvin Powell, who walked in the fourth frame. Powell was washed up in a double play a few moments later and Smith was never in danger again.”

In that 1937 season, Smith led the Negro American League with 11 wins, three shutouts, 99 strikeouts and a 0.859 WHIP. With Smith, Cooper, a couple appearances from Rogan and a terrific season from future Hall of Fame outfielder Willard Brown, Kansas City went 52-19 and captured the pennant.

Smith paced the league in innings each of his first three seasons before adopting a new role in 1941. With the wildly popular Paige now a Monarch, the club maximized ticket sales by starting the well-traveled showman for a couple innings, then letting Smith throw the bulk of the game. But the spectacle of Paige didn’t completely overshadow Smith’s brilliance.

“He had one of the finest curveballs I ever had the displeasure to try and hit,” Hall of Famer Monte Irvin said. “His curveball fell off the table. Sometimes you knew where it would be coming from, but you still couldn’t hit it because it was that sharp. He was just as tough as Satchel was.”

“I can tell you he never brooded about pitching in Paige’s shadow then,” Buck O’Neil wrote in his book, “I was Right on Time.”

“He was playing for a salary, just like everyone else, and this was his job. Satchel was pitching in a ballgame just about every night to draw a crowd, and someone had to pick him up.”

Together, the right-handers shined under that spotlight in Kansas City for seven seasons, winning the 1942 World Series and reaching another in 1946, when they fell in seven games to Leon Day and the Newark Eagles.

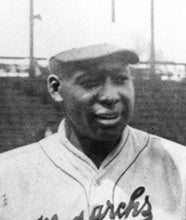

Day, an Alexandria, Va. native, had begun his professional career at age 17 with the Baltimore Black Sox. Then, in 1935, he found a home with the Eagles of the Negro National League II, which had been established two years prior. He played in Newark through 1943, maintaining steady numbers on the mound while emerging as a productive .300 hitter. Day was ahead of his time as a pitcher, with reports citing no windup and deceptively short arm action, two tactics growing in popularity among 21st-century hurlers.

“Day could throw as hard as anyone,” teammate Larry Doby said. “I didn’t see anyone in the major leagues who was better than Leon Day. If you want to compare him with Bob Gibson, Day had just as good stuff. Tremendous curveball and a fastball at least 90-95 miles an hour. You talk about Satchel… I didn’t see anyone better than Day.”

Day returned from military service for the 1946 season. All he did in his first start, on May 5, was toss a no-hitter. “Leon Day, making his first start for the Newark Eagles after two years’ Army service, hurled a 2-0, no-hit victory over the Philadelphia Stars yesterday at Newark,” wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer.

The 5-foot-9 righty had stayed in pitching shape during World War II, playing for the integrated Overseas Invasion Service Expedition and winning the European Theater of Operations World Series in front of massive crowds at Germany’s Nuremberg stadium. But Day injured his arm on a fielding play during the no-hitter and pitched through pain the rest of the season. “It wasn’t the same no more,” he said of his throwing arm in James A. Riley’s “Dandy, Day and the Devil.”

Still, 1946 proved to be Day’s best season — and his last — as he led the league with 13 wins, 14 complete games, three shutouts and 109 strikeouts. He, Doby and Irvin led Newark to a World Series victory over Smith and Paige’s Monarchs.

Despite never playing integrated big league ball, the soft-spoken and humble Day reflected proudly upon his career. “I was glad to play in the Negro Leagues,” he said. “I wouldn’t trade it for anything in the world.”

What Day wanted most was the ultimate reward for a legendary career: A spot in the Hall of Fame. He threw out the first pitch before a Baltimore Orioles game on Sept. 24, 1992, and said, “It would mean a lot to me to get into the Hall of Fame, to be grouped with some of the greatest players in history.”

And on March 8, 1995, just a few days before he passed away, Day received the call from Cooperstown. Rogan’s election followed in 1998, Smith’s in 2001 and Méndez’s and Cooper’s in 2006. Although none lived to see their induction ceremonies, each will live in baseball lore forever for some of the greatest pitching performances and careers in major league history.

Justin Alpert was a digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum