- Home

- Our Stories

- About Wendell Smith

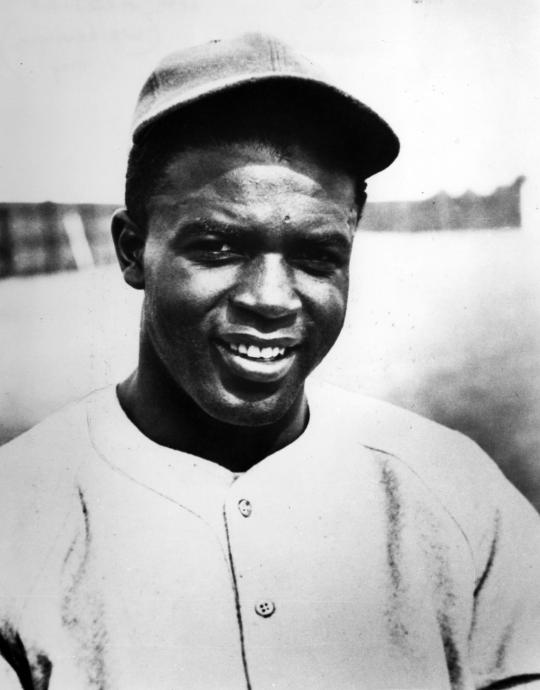

About Wendell Smith

"It was then that I made the vow that I would dedicate myself and do something on behalf of the Negro ballplayers."

--Wendell Smith, reflecting on his Detroit childhood in an interview with Jerome Holtzman in 1971

Motivation: Ford and Egan

By his own account, Wendell Smith grew up largely away from prejudice in Detroit. He was the son of John Smith, a personal chef for automobile magnate Henry Ford. John and the family were often invited to the Ford home for social gatherings, and Smith remembered that he often played baseball with the Ford children. Once as he played, Smith overheard a conversation between his father and Ford. Ford said "He's a fine looking boy, John. What does he want to be when he grows up?" Smith recalled this frustration because the career he wanted—a major league baseball player—was simply not available to him.

Wendell Smith developed into a quality young pitcher on his way to professional ball until a fateful day in 1933. At nineteen years old, Smith pitched a shutout for his integrated American Legion team. After the game, he was approached by Detroit Tigers scout Wish Egan. Egan told Smith that he wished he could sign him to a Tigers contract, but he did not have the authority to sign a black man. Soon thereafter, Smith decided to pursue a career as a sportswriter, hoping he could someday help remove the barriers keeping black ballplayers from making the big leagues.

National Newspaperman and Activist

Immediately upon Smith’s graduation from West Virginia State College in 1937, the Pittsburgh Courier hired him. The Courier was the largest national black newspaper at the time and would come to be best known for launching the World War II Double V Campaign (a media campaign aimed at the African American community which sought victory at home against racism and victory abroad against the Axis powers). The Courier encouraged its writers to pursue Civil Rights topics. After less than a year on the job, Smith put a sportswriter’s spin on Civil Rights by interrogating baseball’s color line. Smith’s first big story emerged during 1939 when he interviewed over fifty white National League players and managers about their thoughts on segregation in baseball. Over 75 percent stated they had no problem with blacks in the major leagues. Smith used this data to put pressure on major league club owners who claimed players would never tolerate a black teammate. By 1945 Smith helped organize tryouts for black players with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Boston Braves, and Boston Red Sox, but each time ownership refused to sign anyone.

Late in 1945, Smith and Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey discussed the possibility of signing a black player. It was Smith who first suggested Jackie Robinson to Rickey. At Smith’s recommendation and after extensive Dodgers scouting and face-to-face meetings, Rickey signed Jackie and assigned him to the Montreal Royals, a triple-A minor league club. Rickey then hired Smith to travel with Jackie throughout the 1946 and 1947 seasons to offer support and counsel. All the while, Smith continued to write his regular columns for the Pittsburgh Courier.

To Chicago

In 1948 Smith accepted a job with the Chicago Herald-American (which would later change its name to Chicago’s American), becoming the first black sportswriter at a white newspaper. That same year he became the first black member of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. It was during this time that Smith drifted away from events in Brooklyn, no longer feeling the need to become personally involved in Jackie’s or the Dodgers’ daily affairs. Over the next ten years, Smith and Jackie drifted apart. Their relationship completely soured by the end of Jackie's professional career in 1956, most likely because Smith disagreed with Jackie’s support for the Republican Party.

In the early 1960s, Smith spearheaded the successful Chicago’s American campaign to integrate Florida spring training facilities. In 1964, Smith accepted a job at WGN, one of Chicago's premier television stations. He worked as a sportscaster and often appeared on WGN’s long-running People to People news program. In later years, Smith claimed his first love was newspaper work and that he became a newscaster because WGN offered to double his salary.

Group, including boxer Joe Louis, Louis Jones, Jackie Ormes, Wendell Smith, Rosyln Lindsay, Louise Barnett, Gladys McCallogh, Cab Calloway, Betty Randolph Dorsey, Freddy Guinyard, Helen Matthews Ball, Elvira Guster, Wilmet, and Thelma Spangler gathered around table in Loendi Club, April 1938. Photo by Charles "Teenie" Harris. Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Recognition

In 1971, Smith was one of ten men selected to be a voting member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame's Special Committee on the Negro Leagues. He and Sam Lacy were the only two committee members who were not directly involved in baseball as either an owner or player. Both served on the committee in 1971 and 1972.

In October 1972, Jackie Robinson passed away. Smith wrote the obituary, and it would be the last article he ever penned. A month later, Smith's health faded as well. He died at the age of fifty-eight, succumbing to a battle with cancer.

Since Smith’s death, numerous organizations have recognized his importance within the realms of sport, journalism, and civil rights. In 1993, Smith became the first African-American recipient of the J.G. Taylor Spink Award for meritorious contributions to baseball writing, accepted by his widow Wyonella. In 2013, Andre Holland portrayed Smith in the Jackie Robinson biopic film 42 showing Smith’s contributions to a wide audience. Also in 2013, the Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism created the Sam Lacy-Wendell Smith Award to be presented annually to a sports journalist or broadcaster who has made significant contributions to racial and gender equality in sports. In 2014, the memory of Smith’s life saw more attention when the Associated Press Sports Editors posthumously awarded Smith the Red Smith Award.

Learn more about Wendell Smith through his papers in the Hall of Fame collection.