- Home

- Our Stories

- #DiamondDebates: The DH

#DiamondDebates: The DH

Whole New Ballgame is a new exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum that chronicles the changing nature of baseball from the 1970s to the present. Using the artifacts, photos and videos from the Museum’s collections, a new and wider interpretive approach examines the game and its culture as a whole. The game’s athletic achievements and evolving nature is celebrated and explained, but so too is fans’ presence and input.

The designated hitter (DH): one of the mostly hotly debated subjects in all of baseball. After more than 40 years of the rule’s implementation, fans, players and coaches still can’t agree. Is the designated hitter good for baseball? Or does it tear up the roots of the game that so many have come to appreciate?

In the late 60s and early 70s, the offensive draught that plagued the American League (AL) seemed to indicate that there was need for action. The 1968 season saw only one American Leaguer hit over .300, and the league average hovered around a diminutive .230. The first response was to disadvantage pitchers, and the mound was lowered from fifteen inches to ten. Initially, it helped. The AL batting average went from .230 to .246, and runs per game went up from 3.41 to 4.09. But the relief didn’t last long. The early 1970s again saw pitching reign supreme as runs per game fell back down to 3.47 and the AL batted a collective .239.

Charlie Finley, owner of the Oakland A’s during the 1960s and 70s, saw the lack of offense as a major problem for attendance. "The average fan comes to the park to see action, home runs. He doesn't come to see a one-, two-, three- or four-hit game," said Finley. With the AL trailing the National League (NL) in attendance by more than 2 million, Finley had a point. But he had a solution, too; the designated hitter. "I can't think of anything more boring than to see a pitcher come up, when the average pitcher can't hit my grandmother,” Finley said. “Let's have a permanent pinch-hitter for the pitcher."

As the main proponent of the DH, Finley wouldn’t let the issue die. So, on Jan. 11, 1973, at a meeting of the major leagues, it came to a vote. American League team owners voted 8 – 4 in favor of the DH. The NL, however, didn’t adopt it. So, from that point on, the two leagues played under a different set of rules.

Fast forward to the present day. In the AL, the DH is alive and well. But, as the NL continues to operate without the DH, the argument surrounding the position persists. Which style of play is better? With the DH or without?

The DH does have its upsides. First, pitchers are usually easy outs. Look to Mets starter Bartolo Colon for evidence. Colon has become somewhat notorious for his comical at-bats, waving so wildly at outside fastballs that he loses his helmet. Aside from a few laughs, Mets fans and players alike aren’t getting much from Colon picking up a bat. Out of 69 at bats in the 2014 season, Colon struck out 33 times and finished with a batting average of .032.

All joking aside, stepping up to the plate doesn’t come without its risks. There’s always the possibility of coming away from an at bat with an injury. Just ask Washington Nationals ace Max Scherzer who sustained a wrist and thumb injury on his throwing hand while batting. After the injury, Scherzer let his opinion about the DH be known. “If you look at it from the macro side, who would people rather see hit: Big Papi or me?” Scherzer said. “Who would people rather see, a real hitter hitting home runs or a pitcher swinging a wet newspaper?” Luckily, Scherzer was able to rebound from his injury, pitching a no-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates later in the 2015 season. But St. Louis Cardinals starter Adam Wainwright wasn’t so lucky. He suffered a serious achilles tendon injury during an at bat. To do something he wasn’t brought into the league to do, Wainwright, a four-time top three finisher for the Cy Young Award, prematurely ended his season. Substituting a DH – a player whose job it is to hit – protects the pitcher while allowing him to do what he does best.

Not only does the DH protect pitchers, but it also injects excitement into the game. Adding more great hitters makes it more likely to see what the average fan comes to the ballpark for. “The designated hitter provides more offense and a more exciting game overall for the fans,” said Baltimore Orioles Owner Peter Angelos. “That is important because baseball has a tendency at times to be slow-moving and unexciting. This adds another dimension of excitement to the game and that's why I support it.”

Recall the 2004 American League Championship Series in which DH David Ortiz helped the Red Sox shock the world, coming up with back-to-back walk off hits to help overcome a three games to none deficit against the Yankees. With younger fans increasingly craving offensive fireworks, a DH in both leagues could be a potential solution.

But it’s not so cut and dry. Not everyone is so homerun-thirsty. Some baseball enthusiasts, like contributing USA Today sports writer Howard Camen, crave the more strategic parts of the game:

“Thanks to the DH, the Junior Circuit has adopted a swing-for-the-fences mentality which precludes half the country from enjoying that added dimension of the game called strategy. I mean real decisions - only seen in the NL. The moves which have you arguing with your buddies the next day. Should the manager have ordered that sacrifice bunt? What was he thinking pulling that double-switch when there was still plenty of time to come back? To me, the only people who benefit from the DH are those 14 or so high-paid, aging superstars who grace us with their presence every couple of innings. Let's go back to playing the game the right way - sans DH."

While the AL relies on a consistent hitter in the DH, the NL has to give it a little more thought, deciding when and where to use a pinch hitter and whether or not to lay down a bunt. Using that kind of strategy and small ball is something that the AL sometimes forgets and the NL is often admired for.

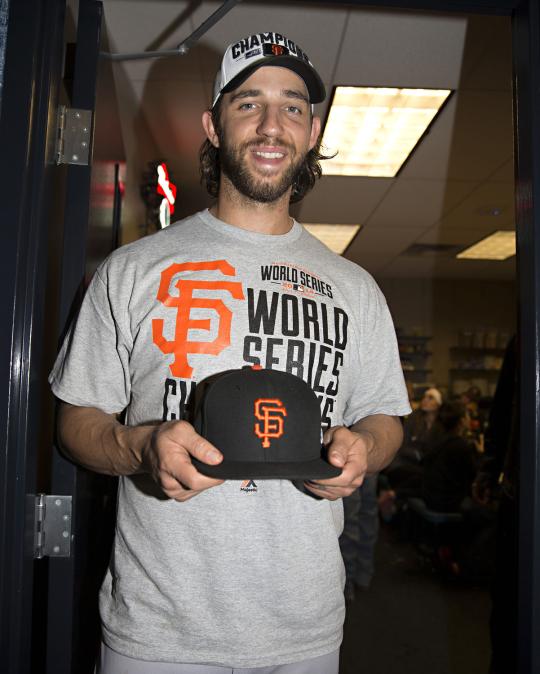

And pitchers are players, too. Why shouldn’t they play both sides of the ball just like everyone else? There are plenty of players who are more defensively gifted than offensively, but they aren’t permanently hit for. And that’s not to say that pitchers can’t hit. They can and sometimes do. In 2014, star San Francisco pitcher Madison Bumgarner had a batting average of .258, a slugging percentage of .470 and an on base plus slugging percentage of .755. Dodgers ace Zach Greinke hit an impressive .328 during the 2013 season. Micah Owings, former pitcher for the Washington Nationals, had a career batting average of .291. Even though pitchers are often viewed as subpar at the plate, they have the potential to create some offense.

Lastly, if pitchers are hit for to generate more excitement, then where does the player designation end? If the goal is to score more runs and hit more homers, why not designate batters to hit for all the players who aren’t great at the plate? Why not hit for all the players hitting under .220 with less than five home runs? Why not designate someone to hit for a player in a slump? That would make the game more exciting, wouldn’t it? At the end of the day, the DH represents a major change to the original rules of baseball, and if the endgame is to produce offense, then what change will be made next to our national pastime to do so?

There’s no clear winner of the argument as evidence for both sides continues to develop. There are pros and cons for both styles of play. As time goes by, the DH debate will only continue to grow. And in the eyes of MLB Comissioner Rob Manfred, there’s nothing wrong with that. “…the difference in the rules is a topic that people love to debate, and I am a huge believer in the idea that if people are talking about baseball, that's a good thing for us.”

Andrew Bevevino was the 2015 digital strategy intern in the Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum