- Home

- Our Stories

- Final call: Legends thrive on season's last day

Final call: Legends thrive on season's last day

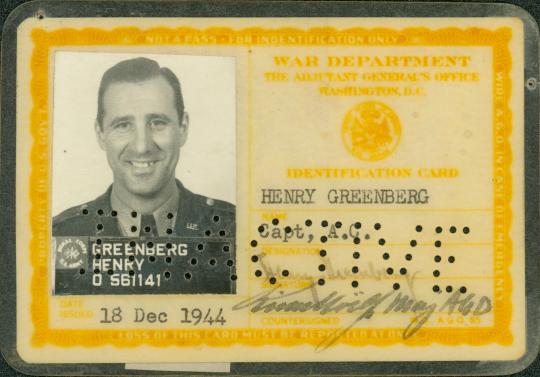

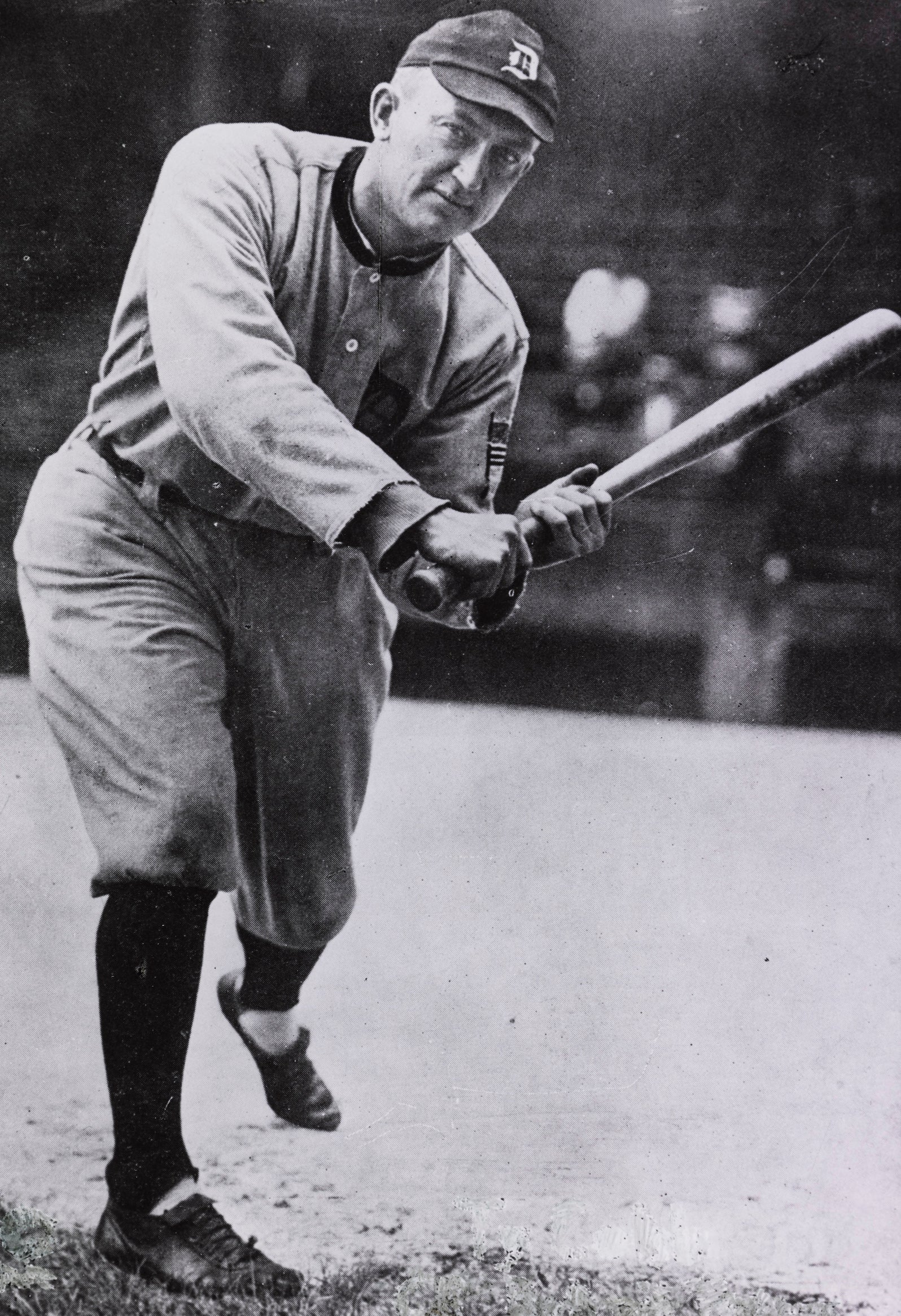

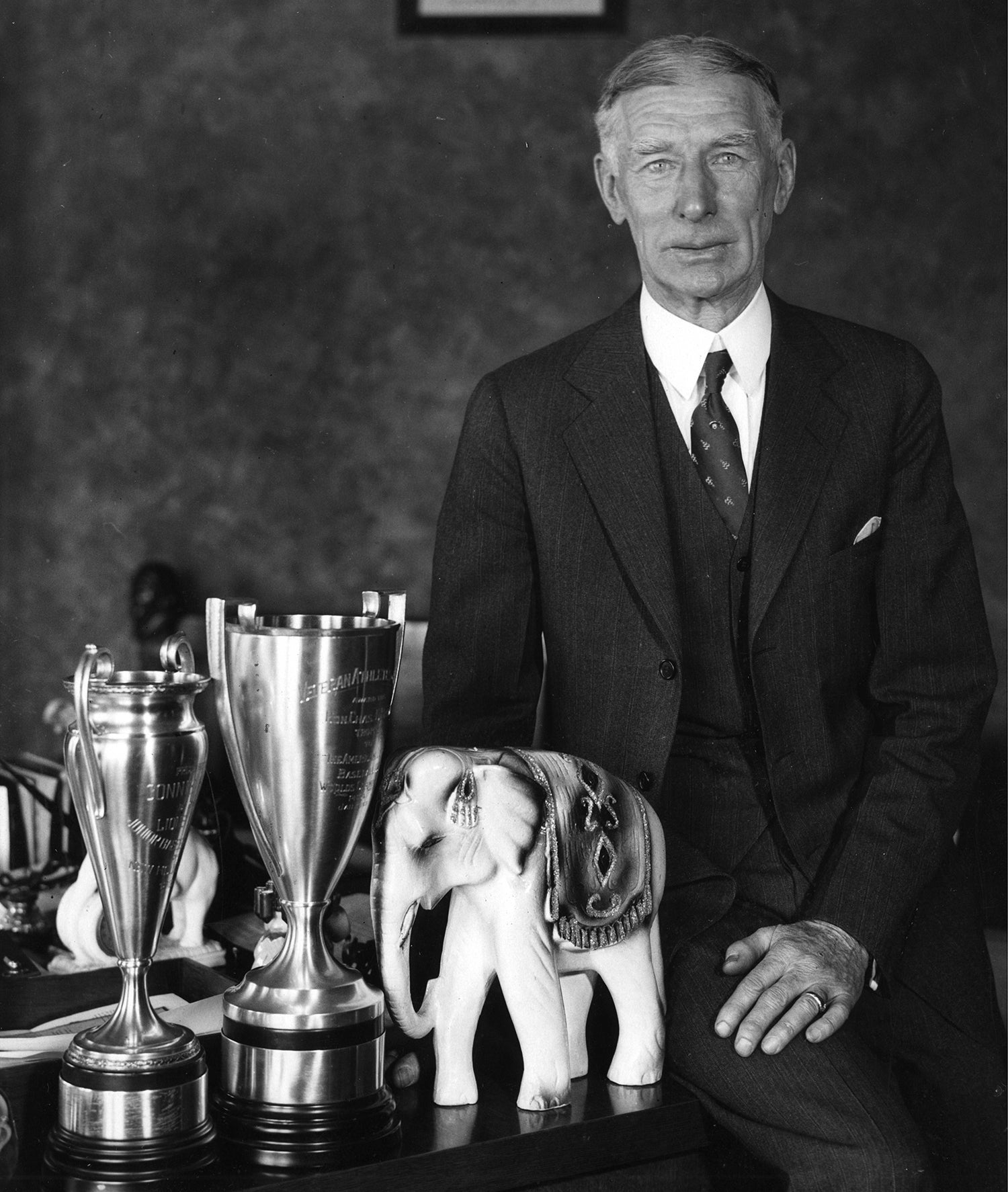

The 1945 Detroit Tigers won the second World Series title in franchise history, besting the Cubs in seven games. But just 10 days prior to the deciding contest, the Tigers club fielding two future Hall of Famers, Hank Greenberg and Hal Newhouser, had been two outs from potentially missing out on the American League pennant.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

On Sept. 30 – the last scheduled day of play in the season – Detroit took the field at St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park for a rain-delayed contest with the Browns. An 88th win would secure the pennant, while a loss would mandate a makeup game and open the possibility of falling even with the second-place Washington Nationals. And for a while, the Tigers appeared to be in trouble.

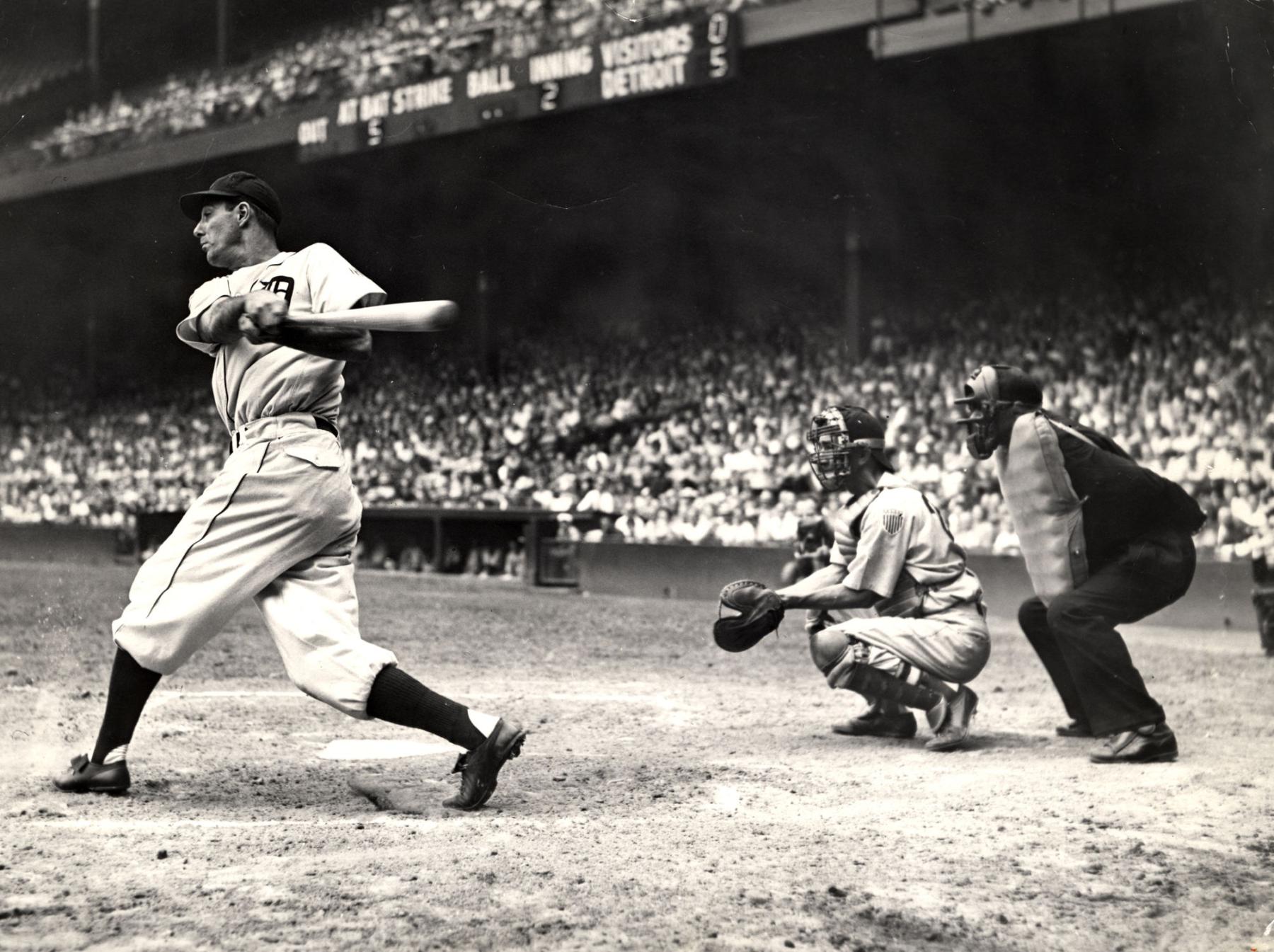

Newhouser had entered in the sixth with a 2-1 lead and extinguished a bases-loaded, one-out fire, only to allow runs in the next two innings. Trailing 3-2 in the top of the ninth, the Tigers loaded the bases and brought Greenberg to the plate with one out. Whereas St. Louis had squandered its sixth-inning opportunity, the Tigers took full advantage as Greenberg ripped a line drive inside the left-field foul pole for a grand slam.

“Call Hank Greenberg a champion of champions,” read the front page of the Detroit Free Press. “Call him a hero of Bengaltown! Call him the man who came through with a ninth-inning home run with the bases loaded to bring the Tigers their seventh American League pennant in 45 years!”

With the game-winning four-bagger, Newhouser had his 25th victory, Greenberg his 13th home run — the outfielder had returned from more than three years of Air Force service to make his season debut July 1 — and the Tigers their shot at a world championship. Greenberg would hit .304 with two home runs and seven RBI in the Fall Classic, winning the second and final title in his career. A legendary feat – made possible by his epic blast on the last day of the season.

Hall of Famers have built their legacies with long and storied careers. They’ve stood out as the game’s greatest from March to October, from ages 18 to 59. But some of their most heroic, unique or simply unbelievable performances have come on the final day of the regular season.

These moments have often featured a player doing what he does best — Greenberg driving in runs, for example. But what about the time Stan Musial, the first baseman and outfielder rightfully known for his slugging, appeared as a pitcher?

Hitting .336, Musial had all but locked up the National League’s 1952 batting title over the .326-hitting Frank Baumholtz. The former’s third-place Cardinals were hosting the latter’s fifth-place Cubs in a Sept. 28 matchup of non-contenders.

Tommy Brown led off the game for Chicago, drawing a walk. Cardinals starter Harvey Haddix then moved to right field, pushing right fielder Hal Rice to center and center fielder Stan Musial — yes, the future Hall of Famer just hours from winning his sixth batting title — to the mound for a showdown with Baumholtz.

“But apparently Baumholtz didn’t want to get something for nothing and went along with the gag and switched from his normal left-handed batting stance to the right-hand side,” wrote the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. “He slashed a drive down to Solly Hemus, who muffed the ball and thus set the stage for the first Cub run.”

With two on and none retired, order was restored: Musial trotted back to center field, Rice returned to right and Haddix toed the rubber once again.

Musial went 1-for-3 with a walk and pitched a hitless, scoreless outing, albeit without an out as Hemus was charged with an error on the Baumholtz liner. Once a minor league pitcher in the late 1930s before injuring his shoulder, Stan the Man had never pitched in the big leagues before Sept. 28, 1952 and would never pitch in the big leagues again.

His .336 average was indeed the National League’s best, marking Musial’s third consecutive batting title and sixth overall. Somehow, .336 was his lowest mark among those title seasons.

“I had a bad year,” he told the Globe-Democrat. “I wish I could have done better.”

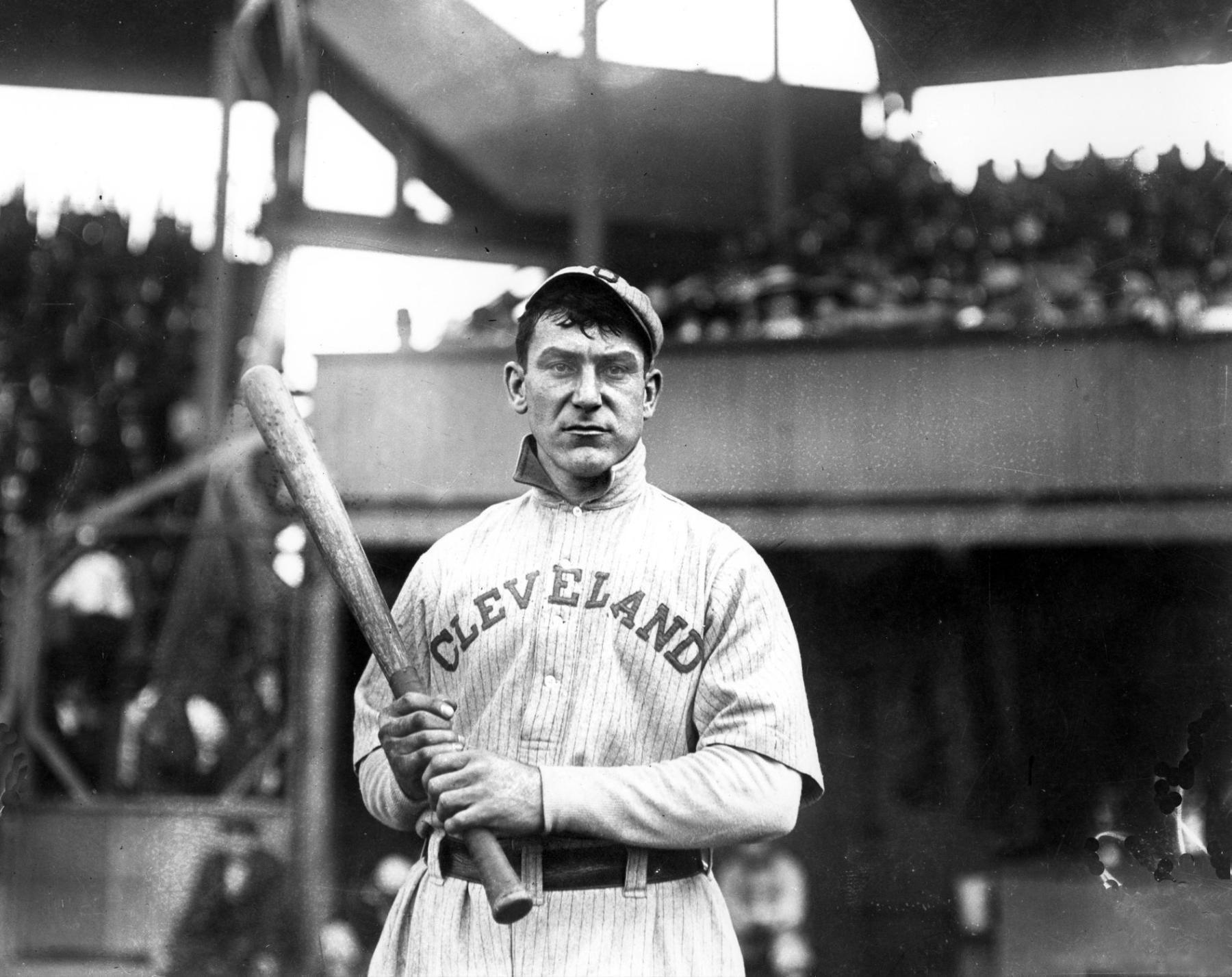

A more contested batting race took place in 1910. And this chase had both pride and a ride on the line. Before the season, Hugh Chalmers of Chalmers Automobile Company had promised Chalmers Model 30 automobiles for the AL and NL batting champions.

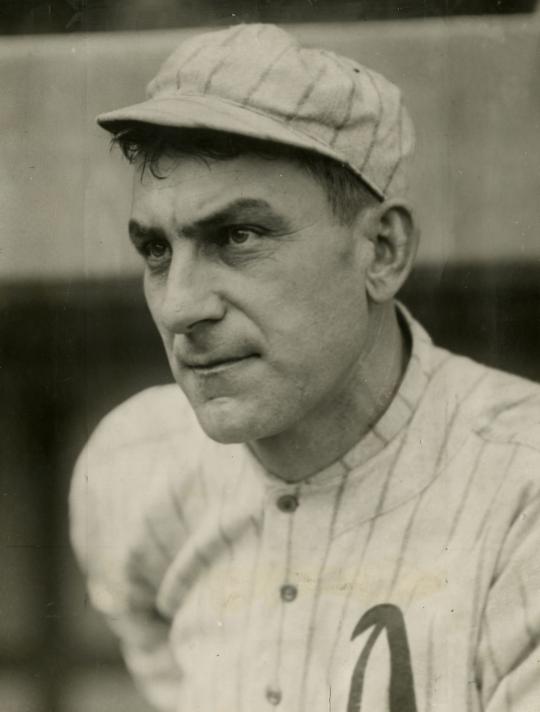

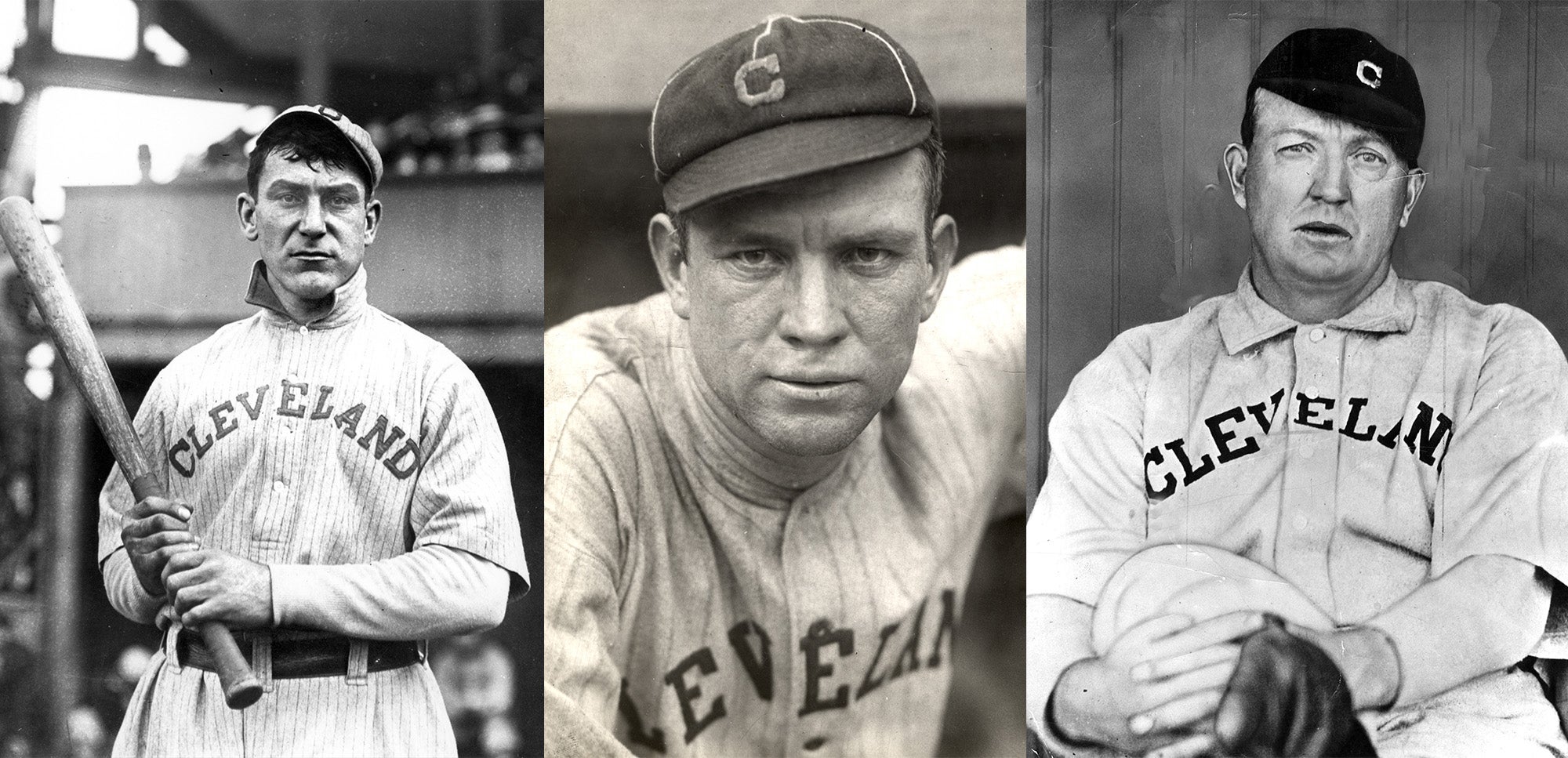

After play on Sept. 16, Nap Lajoie of the Cleveland Naps was hitting .357 while Detroit’s Ty Cobb, 10 points higher at .367, was probably clearing out space in the garage for his new wheels. But Lajoie made a late push, hitting .556 over the next 15 games to reach an astounding .375 mark. Still, Cobb’s season was over and his .384 average appeared insurmountable.

Cleveland had two games remaining: A doubleheader versus the Browns, whose manager Jack O’Connor told third baseman Red Corriden to play unusually deep — possibly to better defend against the red-hot Lajoie, but more likely to spite Cobb and offer Cleveland’s second baseman a chance at the title.

“Reports from St. Louis indicate that the Browns gave a shameless exhibition of lying down in order to make possible the Frenchman’s great batting record for the day,” wrote the Detroit Free Press. “The affair is one that will be certain to create a scandal in baseball circles throughout the country. It will be impossible to convince the majority of fans that the Browns acted honestly in allowing Larry to fatten up his average for the purpose of robbing Cobb of what appeared to be a hard-earned victory.”

An 8-for-8 performance in the twin-bill spiked Lajoie’s average to .384, tying Cobb, but many believed the race had been fixed in Lajoie’s favor and controversy erupted. American League President Ban Johnson declared Cobb had hit .385 and won the title, although Chalmers gifted both players a car.

“I regret very much that any scandal should arise over the batting race,” Chalmers told the Free Press that night, declining to question the Browns’ apparent aiding of Lajoie. “Our company offered this prize with the idea of booming the game and giving the batsmen something toward which to bend their efforts.”

Fast-forward to April 1981, when the Sporting News revealed a bookkeeping error: Cobb’s 2-for-3 line on Sept. 24 — but no other Tiger’s numbers from the game — had been counted twice, hand-made corrections which can be seen in the Hall of Fame’s day-to-day records. With those three at-bats removed, Cobb hit .383 for the season, definitively lower than Lajoie’s .384. Later research lowered their respective averages to .382 and .383, but the point stands: Lajoie was the American League’s outright batting champion in 1910, winning the crown for the fifth time en route to Cooperstown.

Justin Alpert was a digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum