- Home

- Our Stories

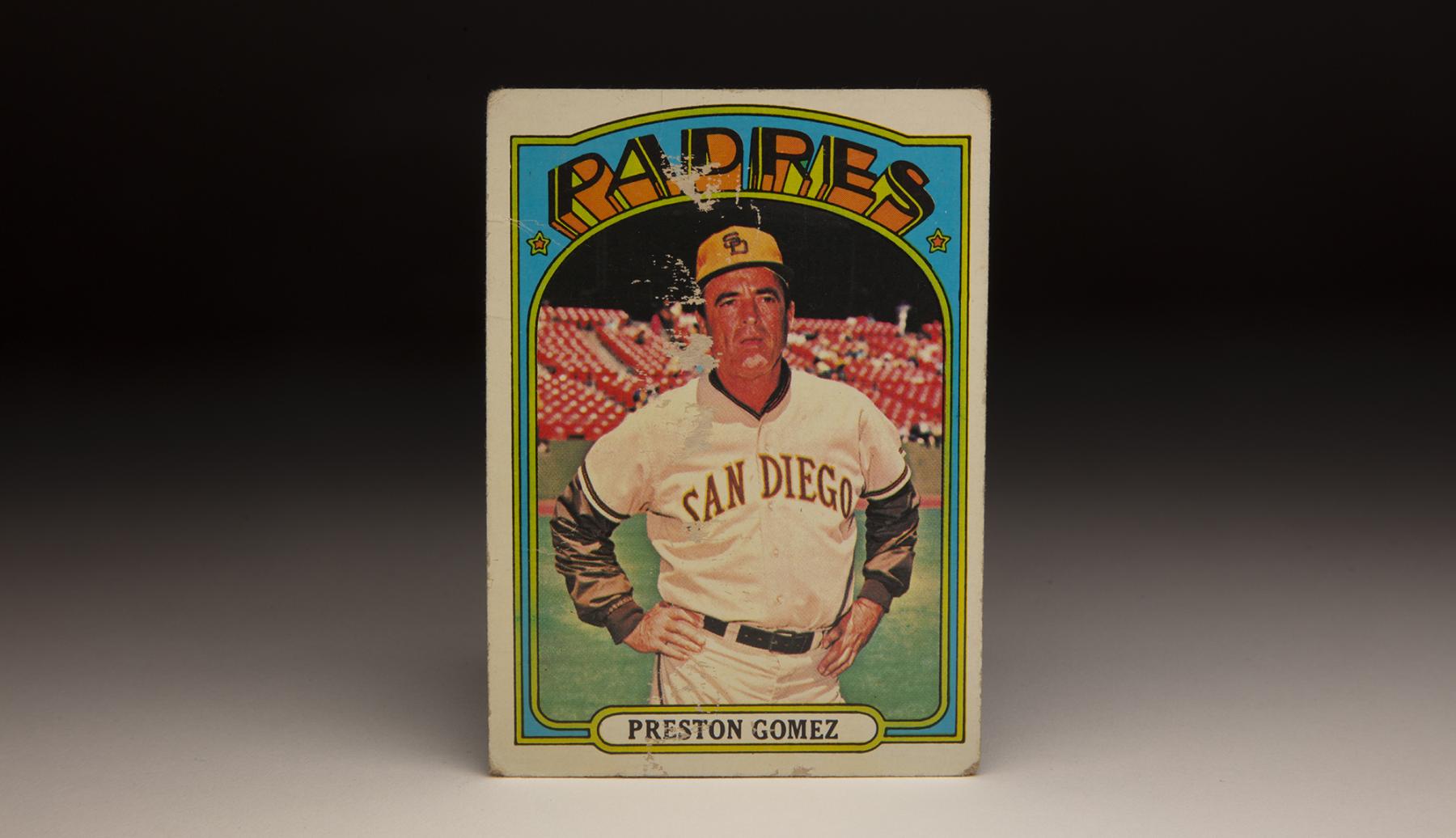

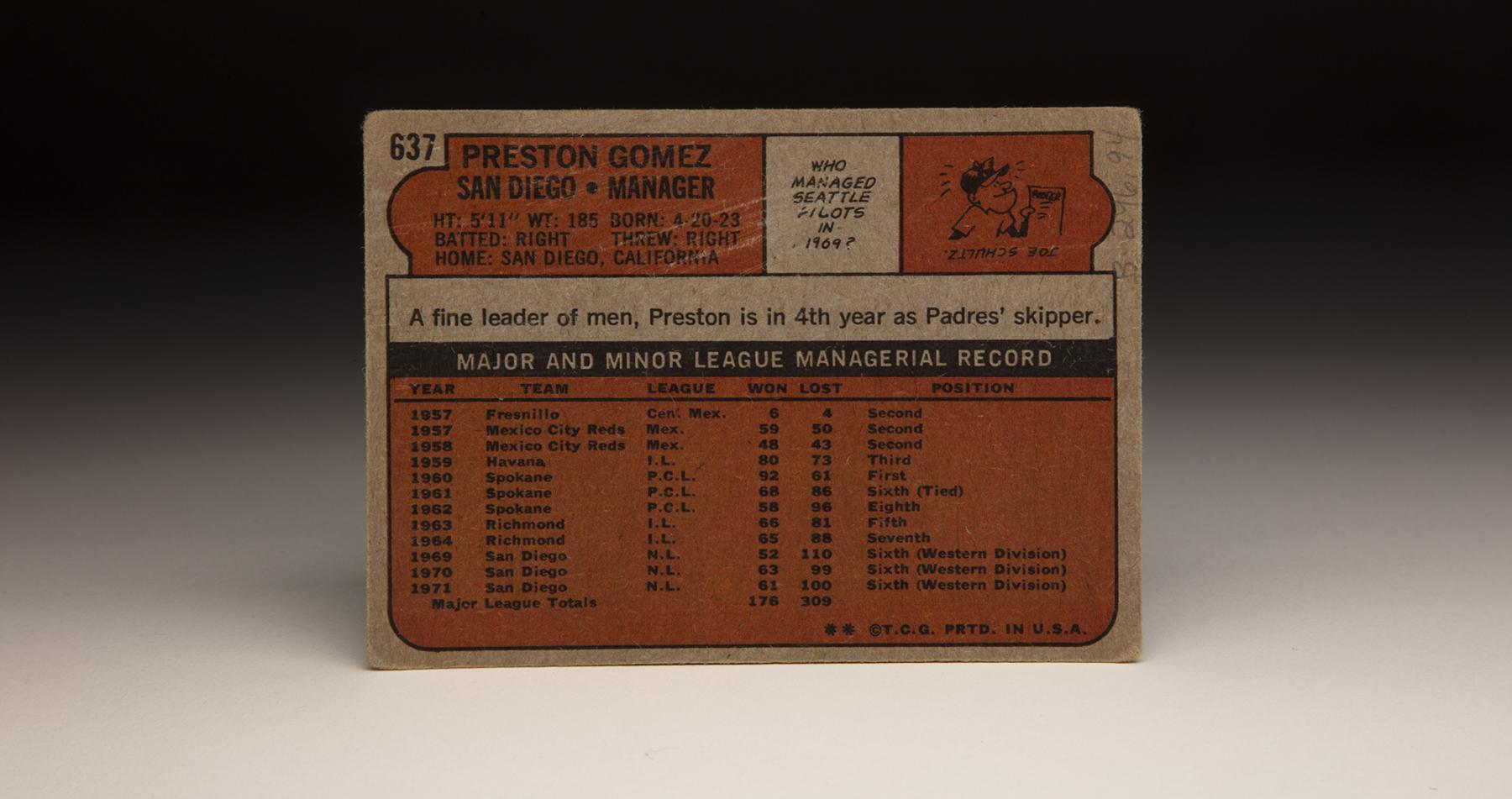

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Preston Gómez

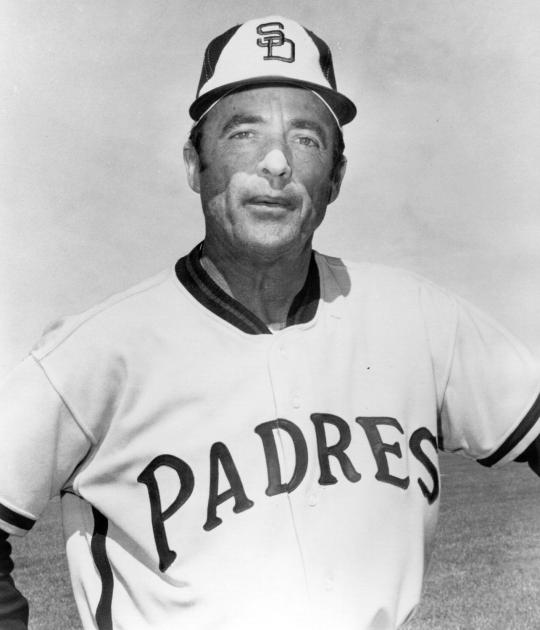

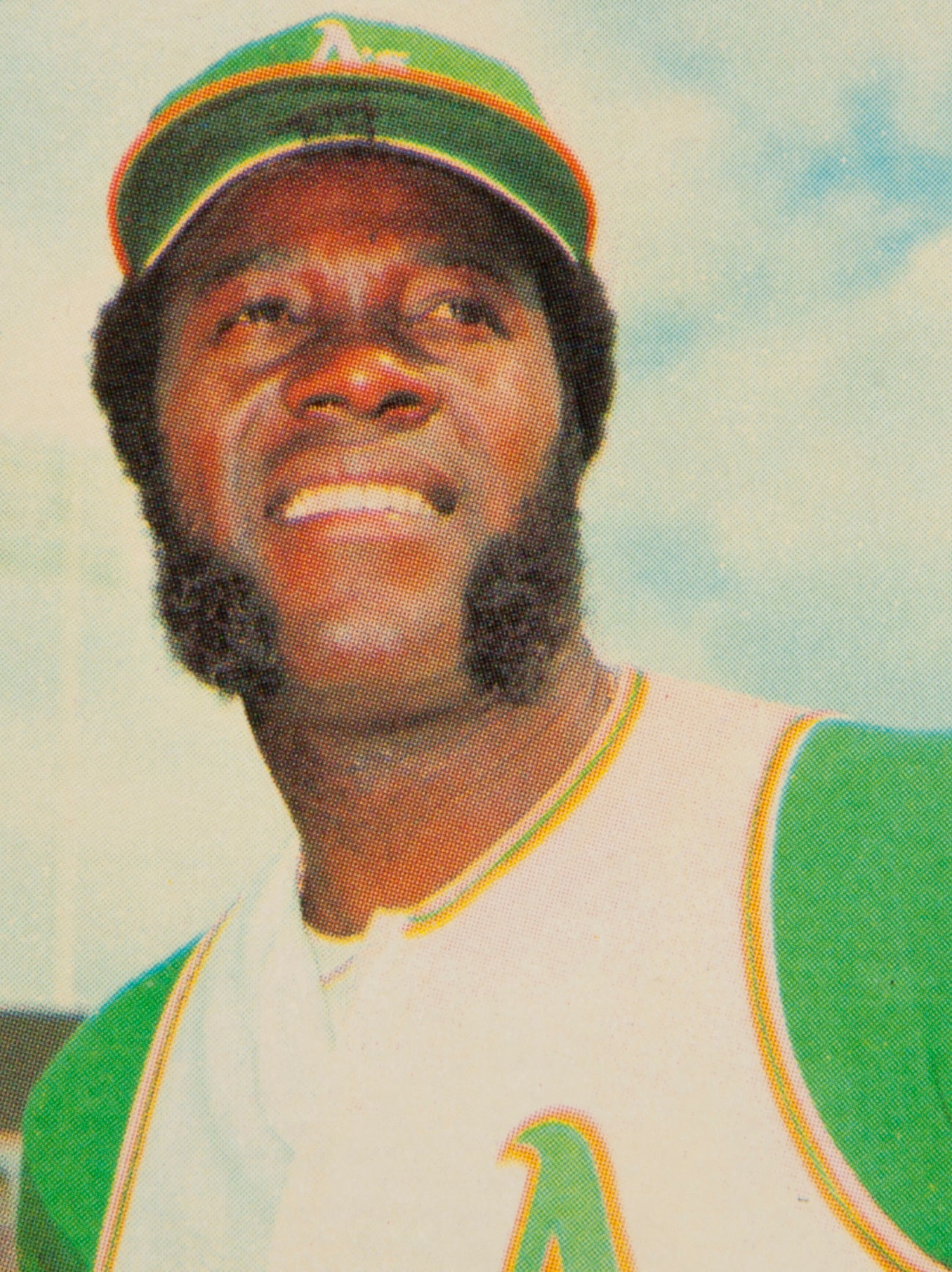

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Preston Gómez

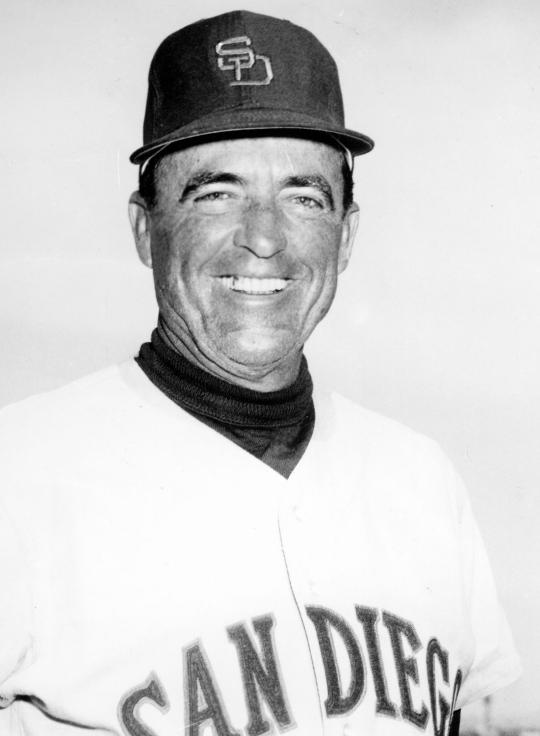

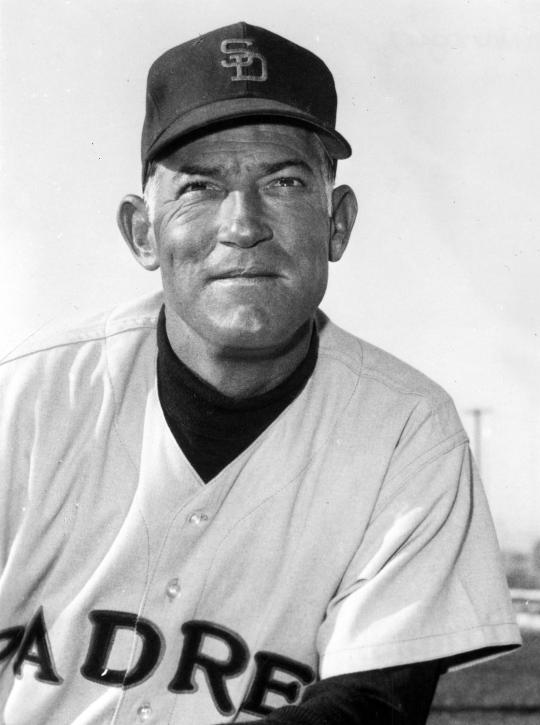

He was the first manager of the San Diego Padres, which was fitting for a man who lived much of his life in nearby Mexico.

Preston Gómez never had a winning season in his seven years as a big league skipper. But as the first Latin American-born manager of a big league team on Opening Day, he helped blaze trails for managers who followed – and left a compelling legacy as a talent evaluator and trusted friend.

Born April 20, 1923, in Central Preston, Oriente, Cuba, Gómez was named Pedro but acquired his nickname from his hometown – located in fertile sugar cane land of the island nation. Gómez played baseball in college in Cuba and was signed by the Washington Senators as one of the earliest Latin American players scouted by that organization.

Gómez appeared in eight games as an infielder with Washington in 1944, collecting two hits in seven at-bats. It would be Gómez’s only big league games during a player career that lasted until the mid-1950s – with stops throughout the minor leagues around North America.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

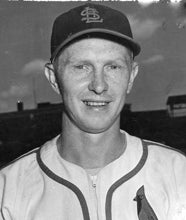

In Cuba, Gómez was mentored by Mike González, who became the first Latin American manager in big league history with the Cardinals midway through the 1938 season and served as a St. Louis coach for years.

“Mike told me many things,” Gómez told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1970. “One that was priceless was: ‘Be calm, observe and don’t say much.’”

Gómez earned his first managerial job with Fresnillo of the Mexican League in 1957 at the age of 34, then took over the Mexico City Reds of the Mexican League from 1957-58, leading the team to two winning seasons.

In 1959, Gómez managed the Havana Sugar Kings of the International League, leading a team flush with former and future big leaguers – including Carlos Paula, Luis Arroyo, Cookie Rojas and Mike Cuellar – to the Little World Series, where the Sugar Kings defeated Minneapolis of the American Association in seven games.

The final game was played in Cuba, which had just experienced its revolution with Fidel Castro coming to power.

“In the deciding game in Havana, Fidel came to the bench and asked who I was going to pitch,” Gómez told the Associated Press. “He said: ‘If you need any help, just call me.’”

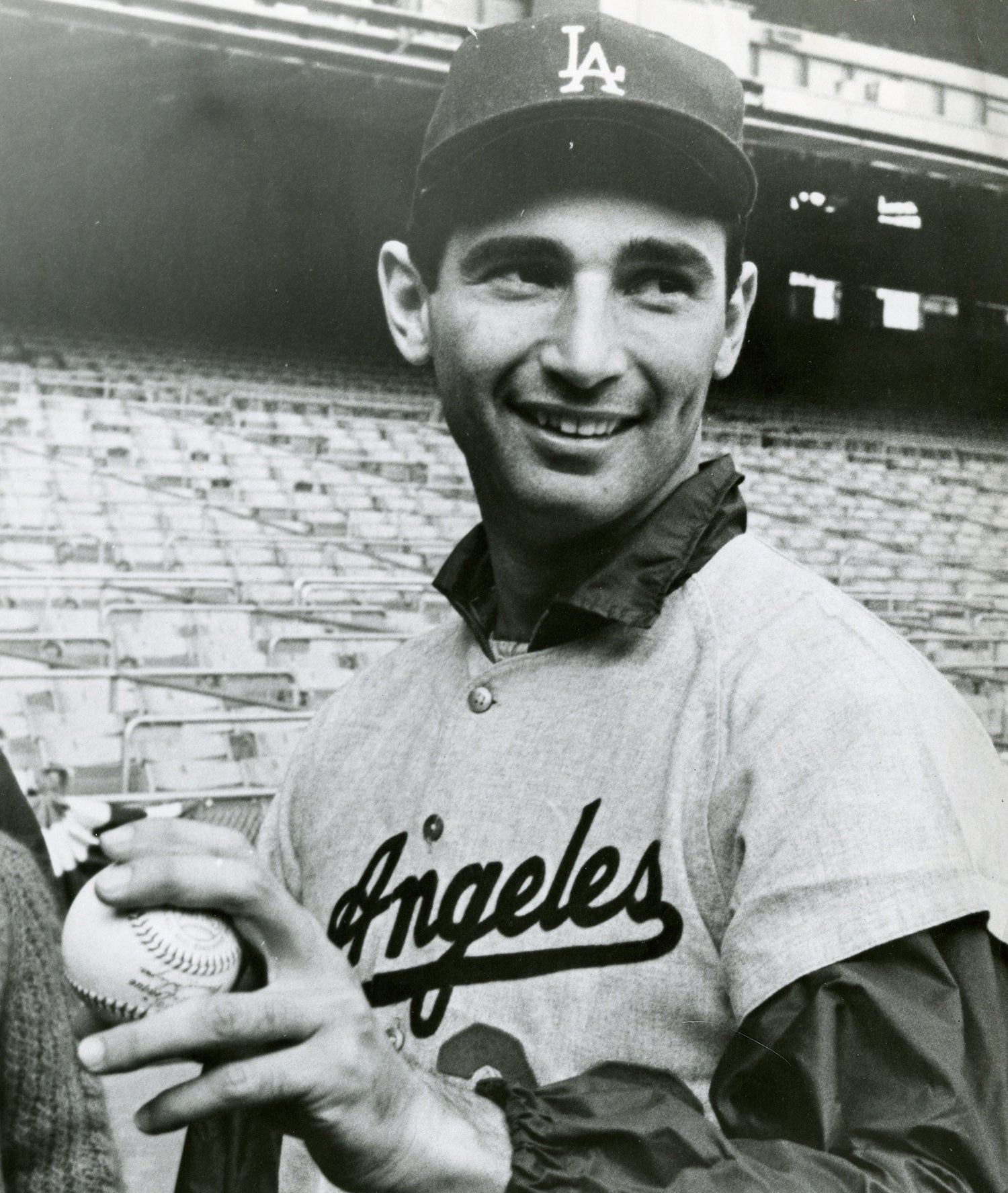

Gómez was hired by the Dodgers following the 1959 season and assigned to manage the team’s Triple-A affiliate in Spokane, Wash. With a roster featuring future Dodgers stars Willie Davis and Ron Fairly, Gómez led the Indians to the Pacific Coast League title, then managed in Venezuela and Mexico following 1960 season.

Spokane finished in sixth in the PCL in 1961 and fell to a record of 58-96 in 1962, but Gómez had already established himself as a top teacher of young talent. The Yankees brought Gómez into their organization in 1963 as part of what was described as a “lend/lease” agreement – meaning the Dodgers could ask for Gómez back at any point. Gómez managed the International League’s Richmond Virginians in 1963 and 1964, posting losing records in both seasons but burnishing his reputation as a mentor.

In 1965, the Dodgers hired Gómez as their third base coach.

“I don’t want timid base runners,” Dodgers manager Walter Alston said at the start of the 1965 campaign. “I want them to be overbearing.”

They were. Gómez helped the Dodgers steal 172 bases in 1965, led by Maury Wills’ big league-leading total of 94. In the World Series against the Twins, Los Angeles swiped nine more bags in seven games – and the Dodgers scored a key insurance run in Game 7 when Gómez waived home Ron Fairly on Wes Parker’s fourth-inning single to give Sandy Koufax a 2-0 lead.

Koufax made that score stand up the rest of the way to give the Dodgers their fourth World Series title in 11 seasons.

“Let me tell you what (Roberto Clemente) told me about Koufax,” Gómez told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle following Game 7. “That guy came down to the National League. He’s in a class all by himself.”

Gómez continued as the Dodgers’ third base coach through the 1968 season. On Aug. 29, 1968 – before the season ended – he was named the first manager of the Padres, who began play as a National League expansion team in 1969.

“Preston is my kind of manager,” Padres general manager Eddie Leishman told the Associated Press after hiring Gómez. “One of the great things about him is his reputation as a teacher of young players.”

Gómez would have his share of young players with the Padres, who struggled to a 52-110 record in their first season. The Padres batted .225 as a team in 1969 and quickly earned a reputation as one of the weakest hitting teams of the era.

“I know you have to be yourself, but I try to have Alston’s patience,” Gómez said during his second year of managing the Padres. “He treats men like men and never second-guesses anyone in front of others.”

And Gómez helped nurture several future managers, including Hall of Famer Sparky Anderson. Gómez managed Anderson in Mexico and Venezuela – and the 34-year-old Anderson was his first hire after being named Padres manager.

“He’s the best third base coach I ever had,” Gómez told the Cincinnati Enquirer of Anderson during the 1975 season. “I watched him from the dugout. So quick and sharp. He didn’t just love it and talk it. He breathed it. I could see that this man was a manager.”

Gómez managed with an eye on the future – even as he was reconnecting with his past. He was welcomed back to Cuba in 1970, as Castro allowed his old friend to return to the country to visit his family. Gómez held baseball camps for youngsters and attended several Cuban League games.

“The newspapers don’t carry American baseball results, but baseball is still king in Cuba,” Gómez told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “You know, 10 years after the door was closed to Cuban players who wanted to leave to play in the States there are still more Cubans in the big leagues than players from other Caribbean countries.”

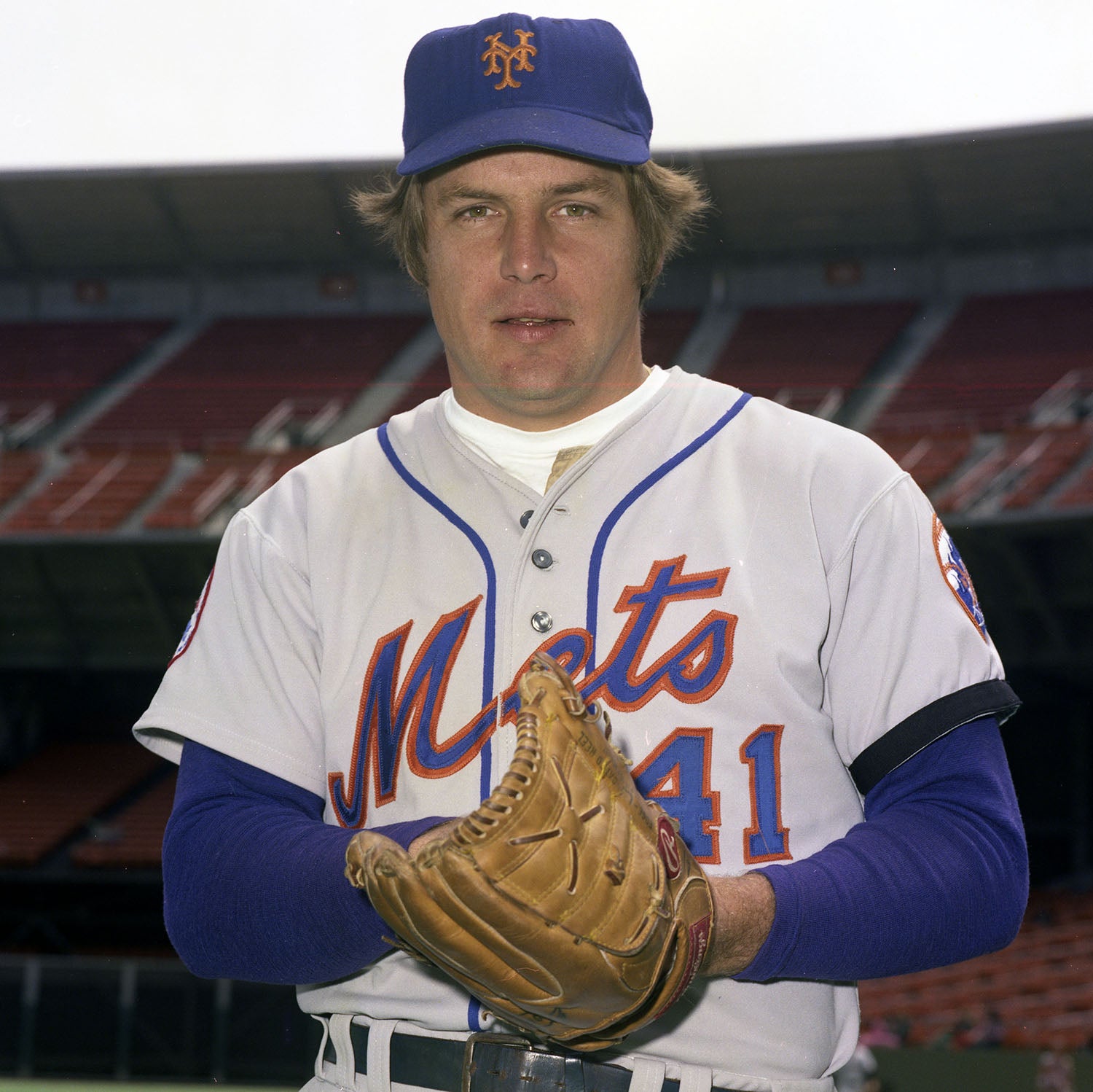

Meanwhile, the Padres were enduring growing pains. The Mets’ Tom Seaver set a record by striking out 19 Padres – including the final 10 of the game – on April 22, 1970. Pittsburgh’s Dock Ellis, reportedly under the influence of LSD, then no-hit the Padres on June 12, 1970.

In 1971, when the Padres finished 61-100, Nate Colbert led the team with 27 home runs – accounting for more than 28 percent of the team’s total.

Eleven games into the 1972 season, Gómez – who signed four one-year contracts with San Diego – was dismissed by the Padres. It marked the first time that Padres general manager Buzzie Bavasi, a longtime Dodgers executive, had ever fired a manager.

“When a team wins, it is a team victory or victory for individual players,” Gómez told the Dayton Daily News. “When a team loses, it is the manager who takes the blame. When you are managing, you do not manage to make friends or you will not last long.”

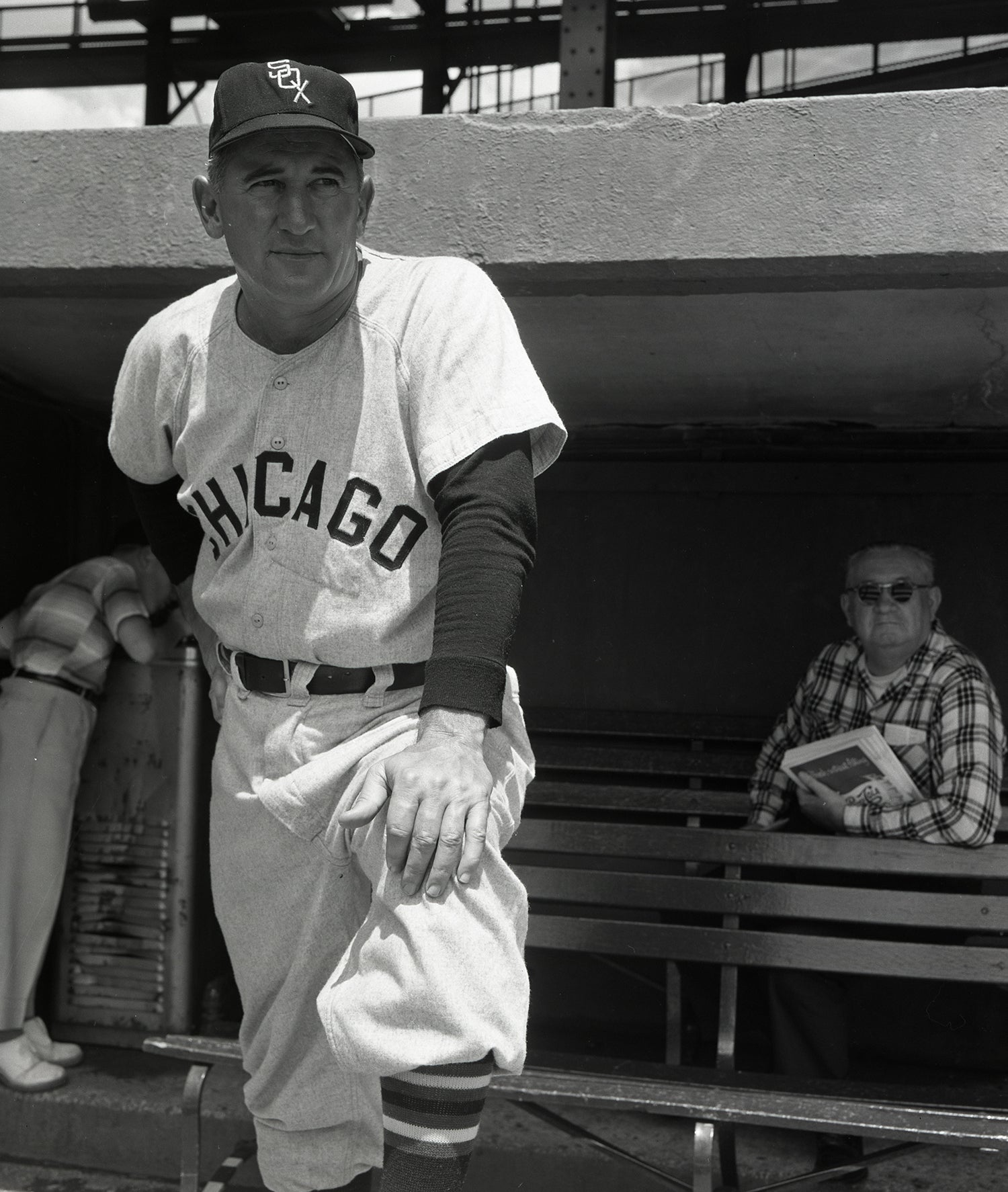

Gómez was not out of work long. He joined the Astros coaching staff in 1973, and when manager Leo Durocher resigned on Oct. 1, 1973, Gómez was named to replace him.

“Give the managers one hour together,” Gómez told the Dayton Daily News at the 1973 Winter Meetings, “and we will make more and better deals than the guys paid to make them all winter.”

The Astros appeared to be ready to contend for their first postseason berth with a roster filled with young talent like César Cedeño, Bob Watson and J.R. Richard. Gómez led the Astros to a record of 81-81 and earned a second one-year deal for 1975, but a 47-80 record on Aug. 18 led to his dismissal.

“I respect Preston Gómez as a man, an individual and as a man with a good baseball mind,” Astros general manager Tal Smith told the Associated Press. “From a realistic standpoint, when a team is 35 games back, you have to say there are problems.”

Gómez’s stint in Houston was not without challenges. He famously removed Don Wilson from a Sept. 4, 1974, game with Wilson pitching a no-hitter through eight innings but with the Astros losing 2-1 thanks to five walks and an error. The Reds won the game 2-1.

It marked the second time in his big league career that Gómez had pulled a pitcher working on a no-hitter – the first coming on July 21, 1970, when he pinch-hit for Clay Kirby with the Padres trailing the Mets’ 1-0. Kirby had no-hit the Mets for eight innings but had allowed a first inning run when Tommy Agee walked, stole second and third and scored on a groundout by Art Shamsky.

“I’ll get paid for winning the ball game, not the no-hitter,” Gómez told the Associated Press after he was roundly booed by the 8,024 fans at the Astrodome after pinch-hitting for Wilson, who had pitched no-hitters in 1967 and 1969 and was bidding to become just the fifth pitcher in history with at least three no-hitters. “This was not one of my toughest decisions. The name of the game is to win.”

Gómez joined Red Schoendienst’s staff with the Cardinals in 1976 and then returned to the Dodgers’ staff in 1977, helping new manager Tommy Lasorda lead Los Angeles to NL pennants in both 1977 and 1978. Following the 1979 season, Gómez was named the Cubs manager on Oct. 2.

“He’s very knowledgeable and patterns himself after Al López,” Cubs manager Bob Kennedy told the Associated Press. “He’s got a one-year contract.”

Ninety games into the 1980 season, the Cubs – who stood at 38-52 – fired Gómez. He returned to Los Angeles, this time with the Angels as their third base coach in 1981. After four seasons, Gómez moved into the front office as a special assistant to the general manager.

He remained a constant among the Angels’ brass until he was struck by a pickup truck at a gas station in Blythe, Calif., on March 26, 2008. Gómez, who was on his way home from Spring Training, suffered head injuries and passed away 10 months later at the age of 85.

Gómez, who spent 64 years in baseball, finished his managerial career with a record of 346-529. But his legacy remains that of a teacher – one who bonded with Latin players through a common language and whose baseball knowledge has been passed on to multiple generations.

“How you run a ball club is in what you do in a clubhouse,” Gómez said. “When my players come in, no matter how early, I want the lineup posted. I don’t want a player to ever ask another or even wonder: ‘Am I in the lineup?’

“As Mike Gonzalez used to say over a beer in his clubhouse office back there in Havana Stadium: ‘A good pool shooter has to hang around the pool table.’

“The ballpark is a pretty good place for a baseball man to improve himself, too.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum