- Home

- Our Stories

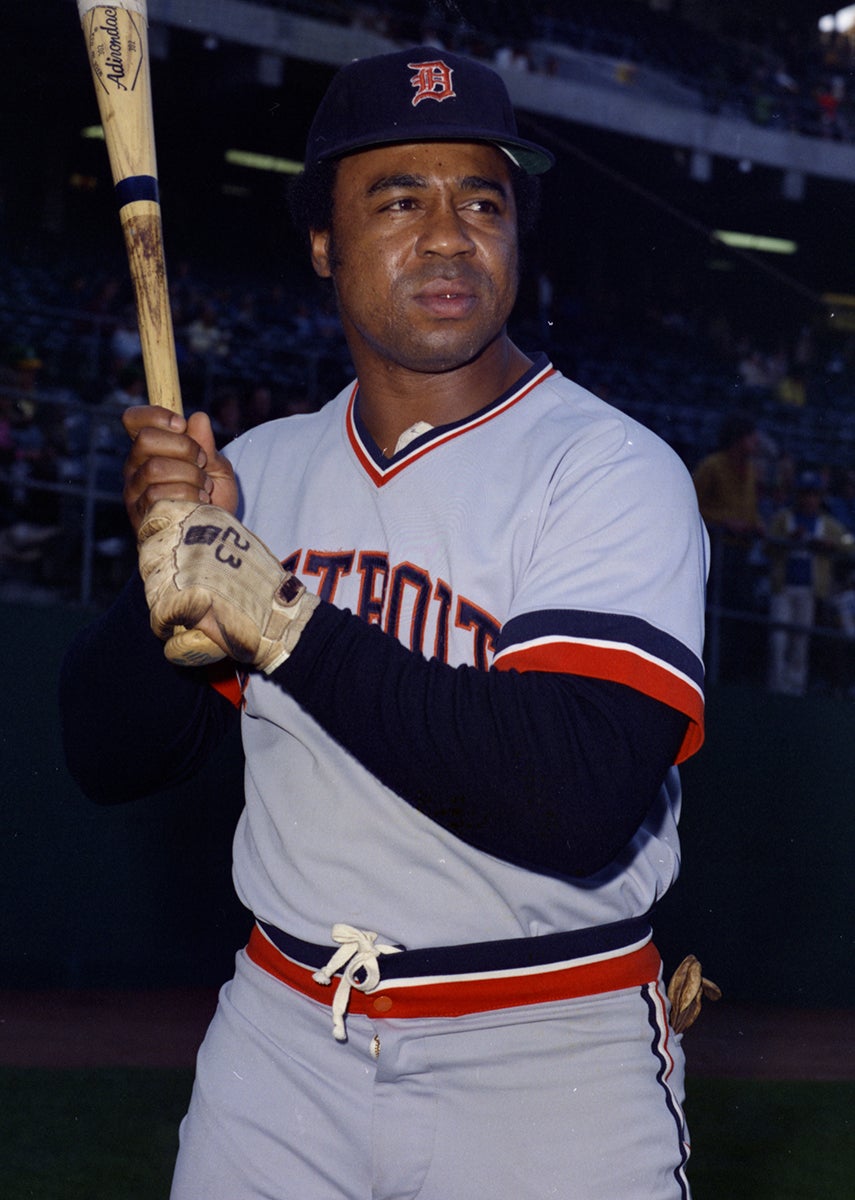

- Horton a hero on and off the field

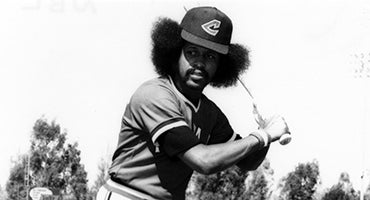

Horton a hero on and off the field

There are two kinds of heroes in baseball. There are the players who excel in the clutch on the field, coming up with the timely hit in the ninth inning, or winning the game with a walkoff home run. Then there are those players who serve their communities, helping children by offering them advice or giving them instruction, raising money for a charitable cause, or committing an act of bravery for the greater good.

It is rare to find players who readily qualify as both kinds of heroes. One of those players, retired now for nearly 45 years, remains a legendary figure in the city of Detroit, where he starred for many years and continues to reside to this day.

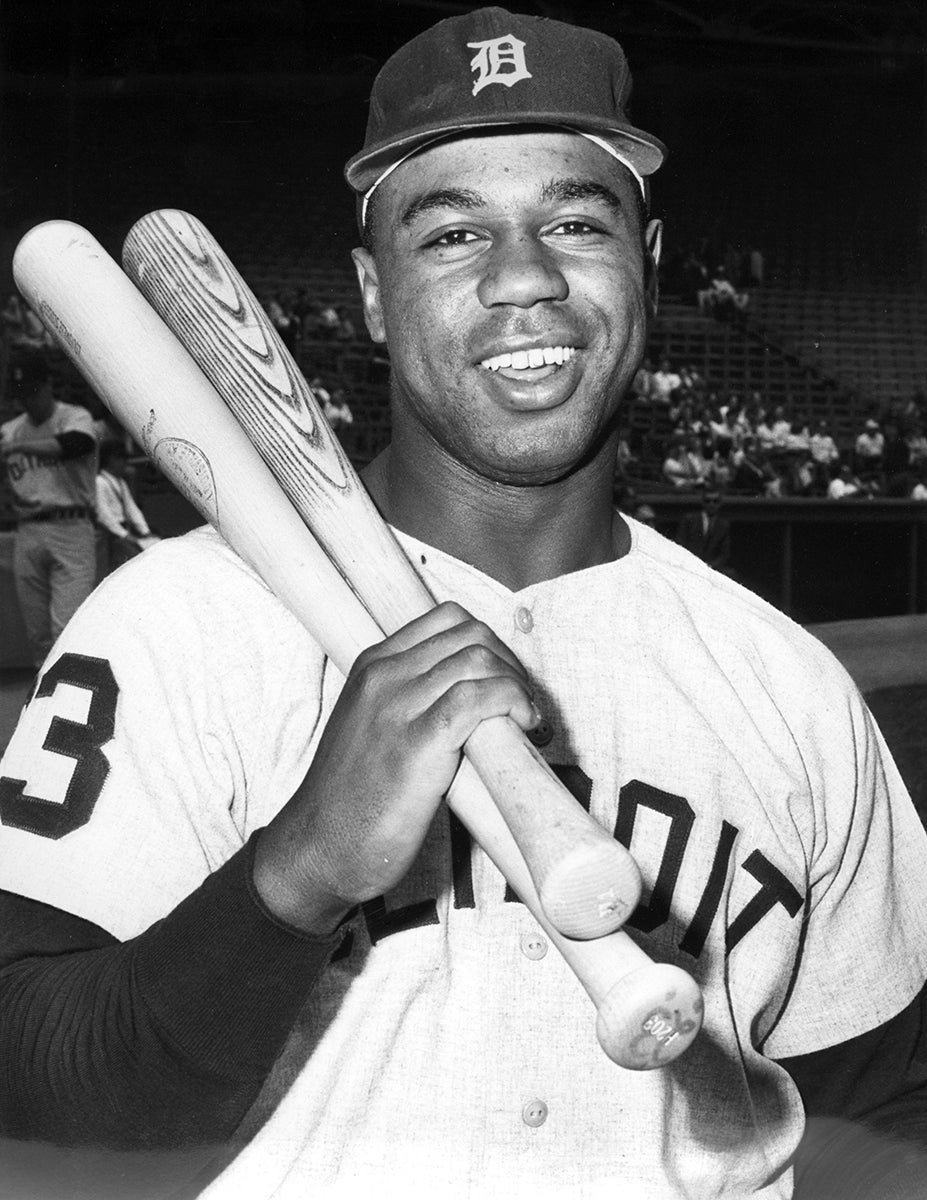

Willie Horton was born in Arno, Va., an unincorporated community for which there are no official population totals. When Willie was just five, his parents made the decision to move to Detroit. Life was not easy in Detroit’s inner city, especially given the size of the Horton family. Along with their parents, 14 children lived in their overcrowded house in the Jefferson Projects, not far from the Tigers’ ballpark, Briggs Stadium.

As a young boy, Horton turned to baseball as the start of a path toward a more comfortable life. He played for an amateur sandlot team, called Detroit Lundquist, leading the club to the national sandlot championship in 1960. Not only did Horton stand out for Lundquist, but he also emerged as the best player at Northwestern High School. In 1959, spurred on by Horton, the Northwestern team had advanced to the city championship game, held at Briggs Stadium. Playing in that title game, the 16-year-old Horton finished the season in storybook fashion, hitting a monstrous 450-foot home run to help seal the championship for Northwestern. The moon shot home run earned him the nickname, “Willie the Wonder.”

That home run cemented Horton’s reputation as a schoolboy legend. The hometown Tigers certainly knew of his talent and had no intention of letting any other major league team swoop in and sign him. With the MLB Draft still four years away from reality, the Tigers targeted Horton as the player they wanted most, while offering him the incentive of signing with his hometown team. Upon graduation from Northwestern in 1961, the Tigers signed him to his first professional contract, while giving him a bonus of $50,000. In 1962, the Tigers assigned Horton to their affiliate in the Northern League, where they switched him from catcher to outfield. Playing for Duluth-Superior, he showed little difficulty in adjusting to pro ball as he hit .295 with 15 home runs, 18 stolen bases and more walks than strikeouts.

As a minor league prospect, Horton drew comparisons to Roy Campanella. At 5-foot-11 and 220 pounds, Horton had a similar build to the Hall of Fame catcher – short, stocky, and packed with power from the right side of the plate. In 1963, the Tigers bumped him all the way up to Triple-A Syracuse. At first he struggled, resulting in a midseason demotion to Knoxville of the South Atlantic League. At that level, he dominated. By the end of 1963, the Tigers brought Horton to the major leagues, a rather remarkable promotion given that he was still only 20 years old.

Believing that Horton was ready, the Tigers brought him to Spring Training in 1964 with the idea that he would have a chance to make the Opening Day roster. He did just that, thanks to a strong spring performance in which he led the Tigers in home runs while collecting 18 RBI. By the fourth game of the regular season, Willie moved into the starting lineup, batting sixth and playing left field. He would remain a regular for the rest of April and the first two weeks of May, but a .167 batting average convinced the Tigers that they had rushed him to the major leagues. So they sent him back down to Syracuse, where he excelled (hitting 28 home runs in International League play) through the rest of the season. The Tigers then rewarded him with a three-game cup of coffee in Detroit to wrap up 1964.

The new year of 1965 brought tragedy to Horton. On New Year’s Day, both of his parents were killed in a car accident. The news devastated Horton, who dedicated the upcoming season to his parents. In the spring, Horton once again made the Opening Day roster, beginning the season as a fourth outfielder before moving into left field fulltime. He played so well over the first half of the season that he was named to the American League’s All-Star team. By season’s end, he had compiled a .273 batting average, 29 home runs, and an OPS of .831. Horton’s performance earned him an eighth-place finish in the AL Most Valuable Player Award voting.

In 1965, Horton also committed his first act of heroism when Al Kaline and Jim Northrup collided in the outfield. Noticing that Kaline was still lying on the ground, Horton ran over from his position in left field. He applied a chest compression to Kaline and pried open his mouth and cleared his tongue, stopping him from choking. Horton kept Kaline’s airway clear until a trainer could come over to apply first aid.

In 1966, Horton posted nearly identical numbers to his 1965 season while also reaching the 100-RBI mark for the second consecutive season. Injuries would limit him to 122 games in 1967, but when he played, he remained productive, helping the Tigers to within a game of the American League pennant. And then there was his impact off the field, which manifested itself in July of that summer.

Severe rioting took hold of Detroit in late July, with the violence ensuing after more than 80 patrons, many of them Black, were arrested at a so-called speakeasy, an illegal after-hours club where alcohol was served without a license. After the early morning arrests of Sunday, July 23, some of the patrons refused to leave the club. A crowd then gathered outside of the establishment on 12th Street, with some people throwing bottles at police officers, whom they believed were racially motivated in attempting the arrests. The police left the area, but more and more people gathered from nearby buildings onto 12th street.

Looting soon ensued, along with the setting of fires. As local firemen tried to fight the blazes, some were attacked by rioters. The violence continued to grow throughout the morning and afternoon hours.

That afternoon, the Tigers hosted a doubleheader at Tiger Stadium. At the conclusion of the second game, Tigers management told players to change immediately into their street clothes and head directly for home while avoiding the 12th Street area.

Horton did not believe that was the proper response. He felt he needed to do something to quell the violence taking place in his city. Still dressed in his Tigers uniform, Horton left the stadium and walked toward the west side of Detroit, where the rioting was taking place. When he arrived at the scene of the rioting, he climbed onto the bed of a parked truck and began to address the rioters directly. Hoping that they would listen to him, given his status as a local sports figure, he told them to head home. They did not listen, instead remaining in place. By that night, with the riots having intensified, eight people lost their lives. More would die in the coming days.

Years later, in an interview with the Sporting News, Horton recalled his thinking in heading directly for the riots and trying to talk to those involved. “People were worried and concerned about me being hurt while I was trying to bring peace,” Horton said. “I saw hope there. A story to be told. But I told them this wasn’t the way to do it. Don’t loot. Don’t destroy your neighborhood. This is your neighborhood. Your schools.”

The rioters refused to listen to Horton that day, but he received overwhelming praise from the community for an act of bravery. Given the violence at hand, and with no security to protect him, Horton had put his safety and life on the line. It was a kind of leadership rarely exhibited by anyone of celebrity status, but also the type of courage in action that typified Horton throughout his career.

Horton’s efforts certainly caught the attention of the Detroit media, but his heroism likely did not surprise many of his Tiger teammates. They had come to respect the quiet left fielder for his strong character, his principles, and his exemplary work ethic. Horton also drew the attention of the Black community. He was one of a handful of Black players who played for the Tigers in 1967, along with reserve infielder Jake Wood, backup outfielders Gates Brown and Lenny Green, and pitcher Earl Wilson. Even more significantly, Horton represented the team’s first Black star. That made him especially popular with Black fans throughout Detroit, helping to boost the team’s following in the minority community.

In the meantime, the 12th Street riots persisted for several days, prompting President Lyndon Johnson to summon the National Guard to the Motor City. By the end of the riots on July 28, the toll had reached devastating levels. Forty-three people dead, while 450 others were injured. More than 7,200 arrests took place in a city where 2,000 buildings were damaged by fires.

The violence left parts of Detroit in tatters while creating an air of discontent that lingered into 1968. As for Horton, he only elevated his on-field performance in the summer of ‘68. Even in the Year of the Pitcher, Horton improved his offensive numbers, hitting a career-best 36 home runs, raising his OPS to .895 and contributing enormously to an American League pennant for the Tigers. Horton finished fourth in the league’s MVP race, just behind two other Tigers: first-place finisher Denny McLain and runner-up Bill Freehan.

Horton has long believed that the Tigers’ success in 1968, culminating in a World Series win over the St. Louis Cardinals, helped to heal a fractured city. It’s a point that has been refuted by some skeptics, but a connection that Horton continues to support. As Horton said in a 1997 interview: “[1968] was a win for the entire city of Detroit. It came a year after riots had torn up our streets, our people, our relationships. I remember walking down Livernois Avenue during the summer of ’67 and seeing all the destruction, all the terror.”

In Horton’s mind, the Tigers’ success helped Detroit make the transition from devastation to hope. “It was a completely helpless feeling,” said Horton of what he saw in 1967. “So ’68 brought people together at a time that was so very important.” Horton believes the Tigers created unity by giving citizens a chance to gather in a peaceful and welcoming atmosphere at the ballpark.

As if Horton had not already made himself into a heroic figure in Detroit, his play in the 1968 World Series only furthered his legend. In the seven games against the Cardinals, he batted .308, reached base 44 percent of the time, contributed a home run and also excelled on defense. In Game 5, Horton threw a powerful, one-hop strike to Freehan, nailing a surprised Lou Brock at the plate. The play seemed to ignite a change in momentum in the Series, as the Tigers rallied to win Game 5, before winning the sixth and seventh games.

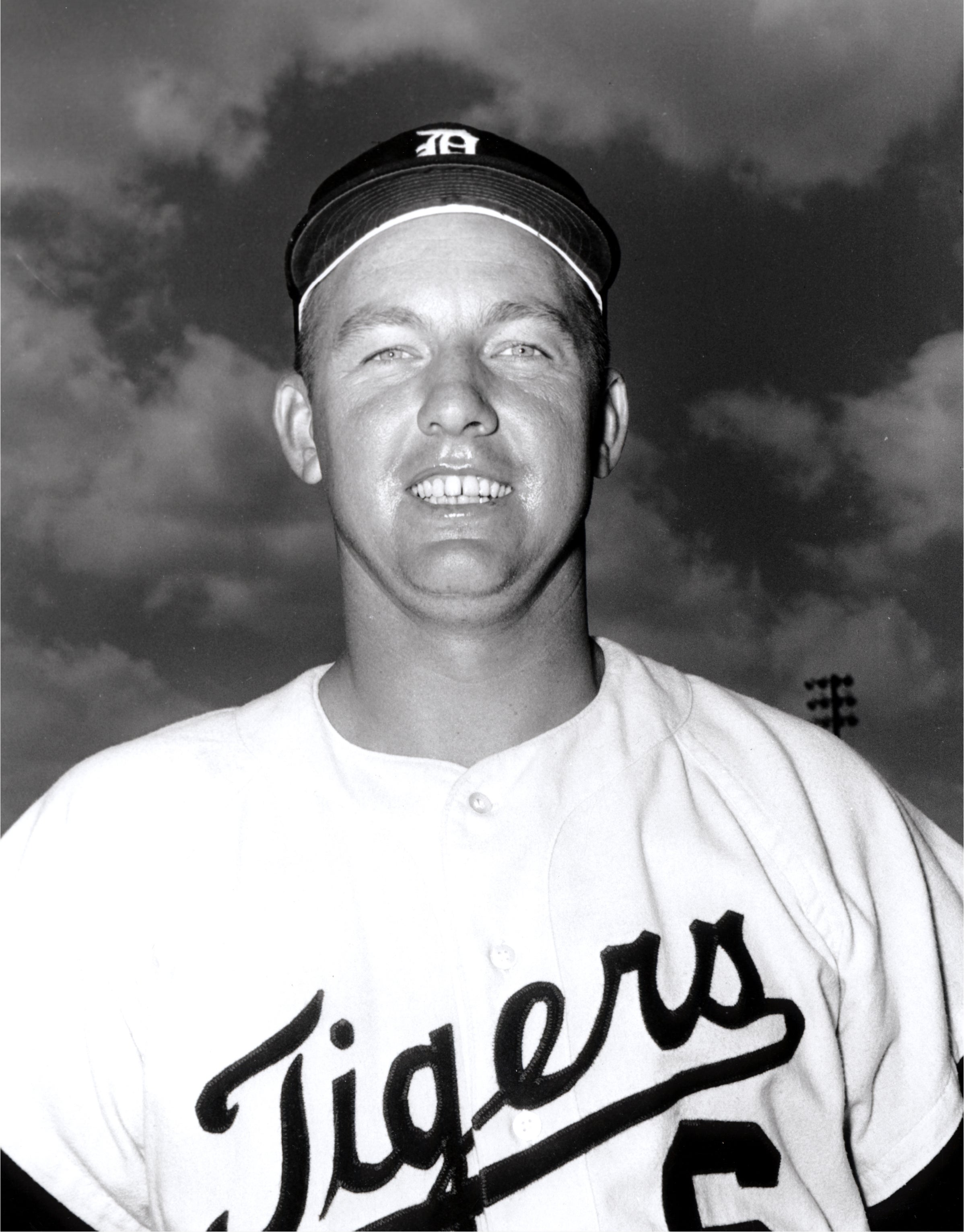

For the next several seasons, Horton remained a productive power hitter, but there were moments of turmoil. One occurred on the final day of the 1971 season, when Horton failed to run hard to first base on an infield grounder. Tigers manager Billy Martin, not one to tolerate a lack of hustle, pulled Horton from the game. Horton was not happy about being benched and said that his days in Detroit had come to an end. But Horton would patch up his differences with Martin and remain with the Tigers.

In 1972, Horton reported to Spring Training well above his normal playing weight, again upsetting Martin. Martin responded by platooning Horton with another veteran, the left-handed hitting Gates Brown. Limited to 108 games and a .231 batting average, Horton took solace in the Tigers winning the American League East. He also became motivated to lose weight and improve his conditioning during the winter.

In 1973, Horton reported to Spring Training slimmer and in better shape. Although soreness in his legs limited his playing time, he lifted his average to a career-high .316 and earned a selection to the All-Star Game. He also seemed to benefit from the presence of a new roommate, Frank Howard. Both established veterans, Horton and Howard found much in common and became good friends.

Injuries became more of a problem for Horton in 1974, when he played in only 72 games, setting the stage for a transition to a designated hitter role in 1975. He remained in that role almost exclusively through the next two seasons. With the retirement of Al Kaline and the release of Norm Cash in 1974, Horton took on even more of a leadership role with the Tigers.

In 1977, Horton began the season with the Tigers, playing on Opening Day before being benched for the next several days due to a logjam of designated hitters and outfielders. Then came a strangely timed decision that changed his career. On April 12, the Tigers made an unusual early-season trade by sending Horton to the Texas Rangers for a relatively little known relief pitcher named Steve Foucault.

The trade, which shocked many Tigers fans, marked the start of the journeyman portion of Horton’s career. For the next few seasons, he bounced from team to team, putting in short stints in Cleveland, Oakland and Toronto, before playing his last two seasons with Seattle. In 1979, he enjoyed a remarkable rejuvenation with the Mariners, playing in all 162 games as a DH and earning American League Comeback Player of the Year honors.

After an ill-fated return to Texas, and two go-rounds in the Pittsburgh Pirates’ farm system, Horton played one season in the Mexican League before retiring. Two years later, he returned to the game when his former manager, Billy Martin, hired Horton as one of his coaches with the New York Yankees. The two men had clashed at times during their time in Detroit but were now friends. Martin hired Horton to serve as a “tranquility” coach, a term that had never before used in baseball’s lexicon. With a team full of rebellious players, Martin looked to Horton to maintain order in the clubhouse through his sheer physical presence. With Horton around, Yankee players figured to be less inclined to challenge the authority of the feisty Martin.

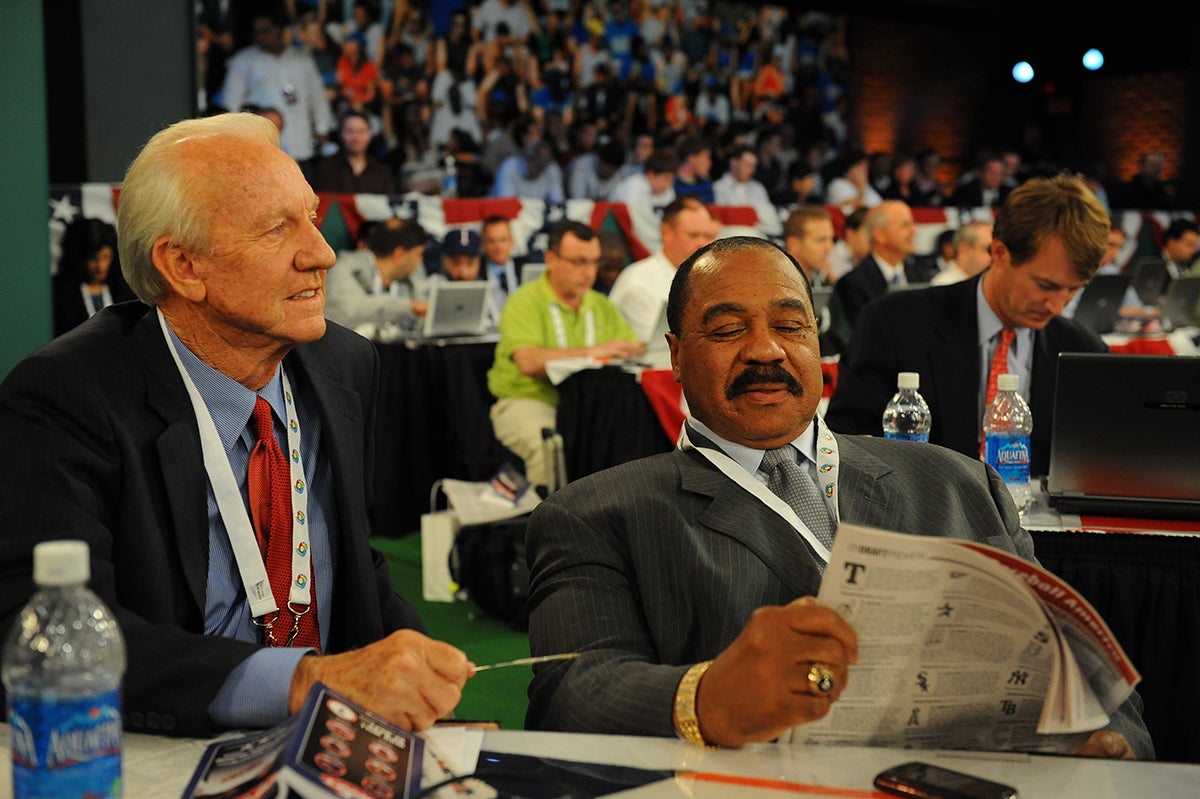

Horton’s coaching career would later include stops with the White Sox and the Tigers. But he did not make a more permanent return to the organization until 2001, when Tigers owner Mike Ilitch hired the former star outfielder to serve in the team’s front office. The hiring came one year after the Tigers retired Horton’s No. 23 and unveiled a large, bronze statue of their former slugger outside of the left field stands at Comerica Park.

Horton made additional news in 2004 when the Michigan legislature designated his birthday, October 18, as “Willie Horton Day” throughout the state. The Detroit City Council also honored Horton with the “Spirit of Detroit Award” for his community service. These were honors well deserving for the man who had made such heroic efforts in 1967 and who had continued his community work on behalf of so many Detroit-based organizations, including the Police Athletic League, the United Way and the Boys and Girls Clubs of America.

As a front office representative for the Tigers, Horton also did the hard work of creating a connection between the franchise and the Black community of Detroit. In 2009, the Tigers created the Willie Horton Legacy Award, given to retired Black players who once starred for the Tigers. Winners of the award have included Gates Brown, Earl Wilson, Lou Whitaker and Chet Lemon.

Horton’s impact on the city of Detroit and the Tigers franchise remains enormous. If anything, his legacy continues to grow. In some ways, it seems that Horton is more famous and more recognized in Detroit now than he was as a player for the team back in the 1960s and 70s. In a sense, that should come as no surprise. After all, real life heroes like Willie Horton are hard to come by.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum