- Home

- Our Stories

- McLain’s 30th thrilled the baseball world

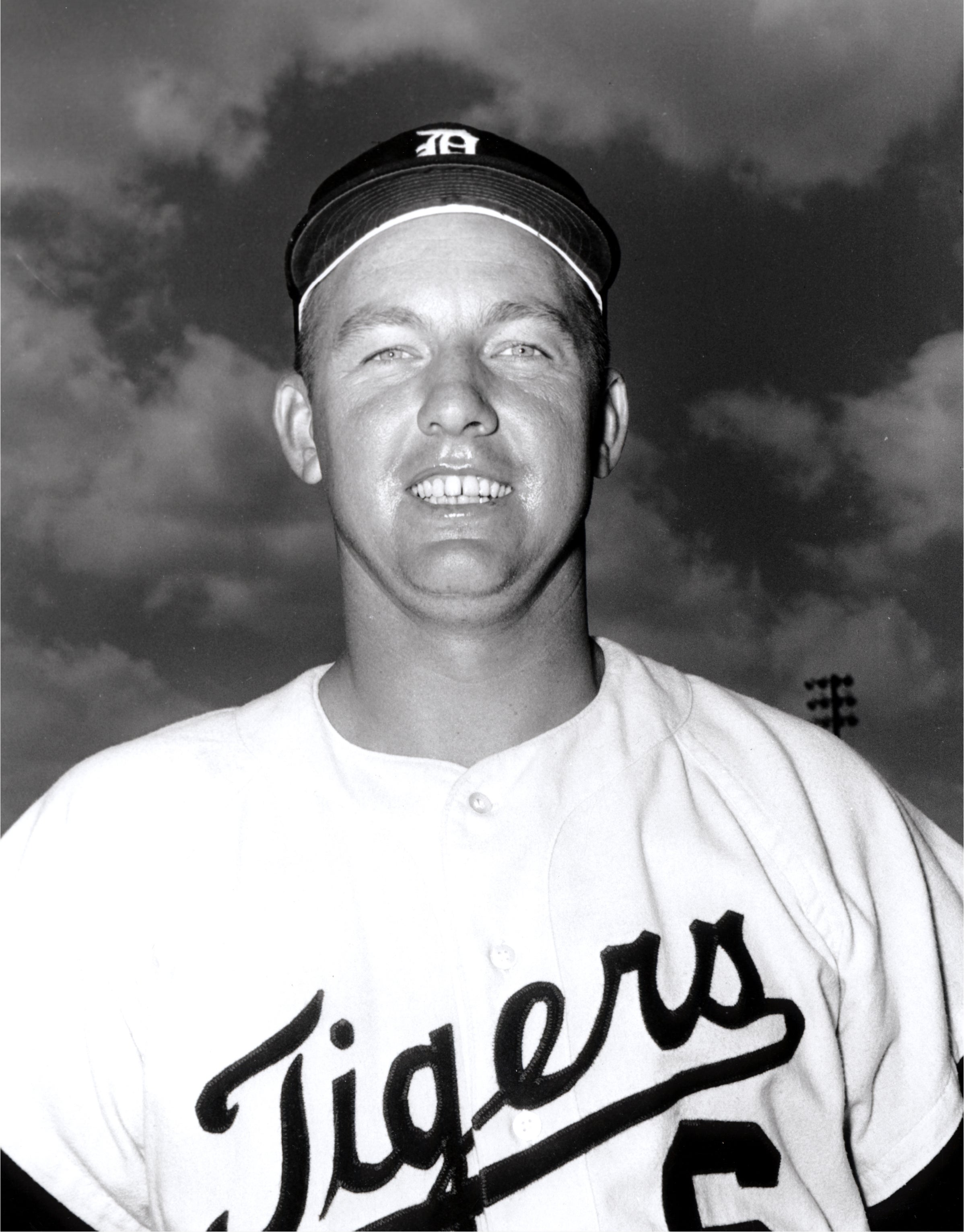

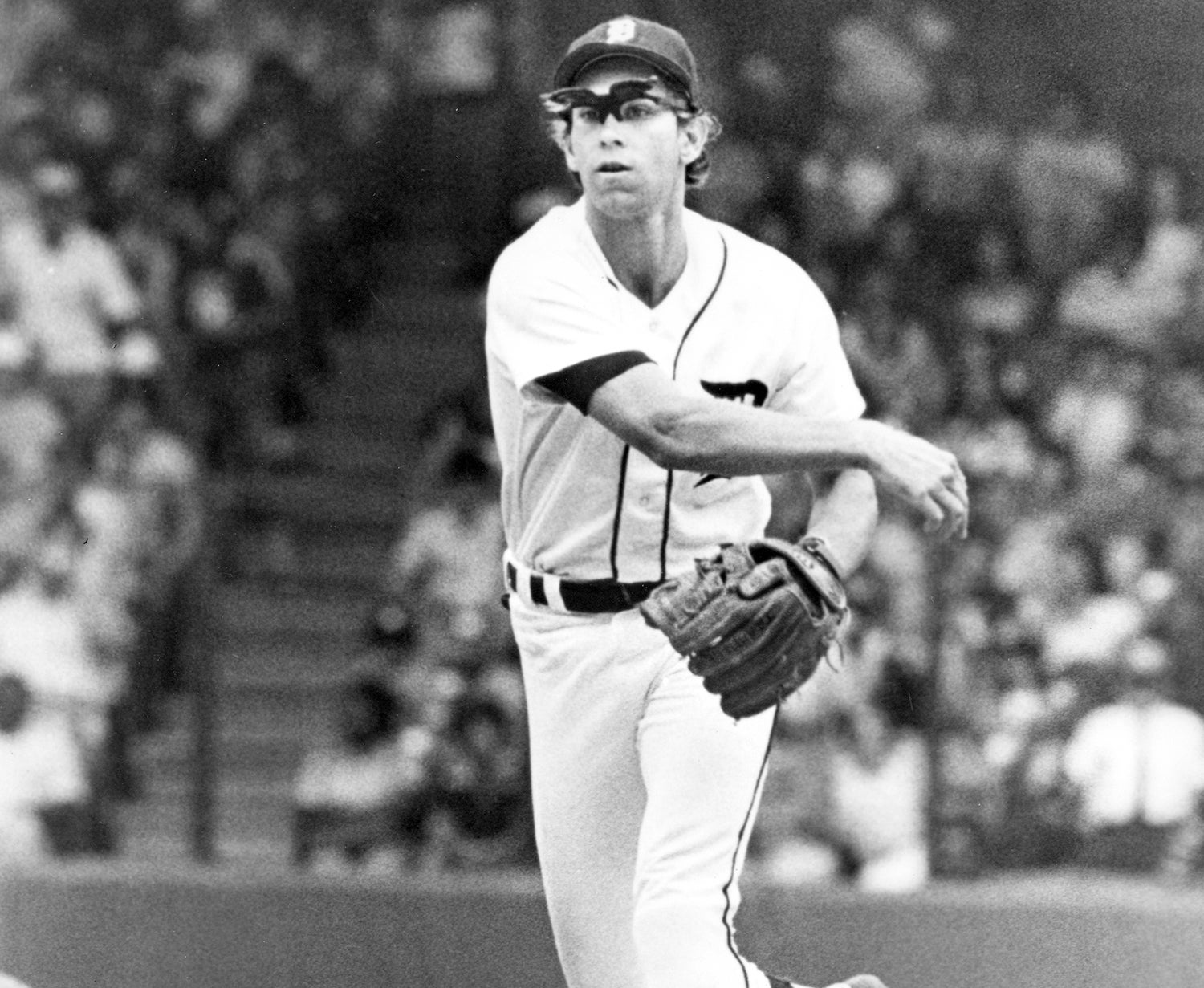

McLain’s 30th thrilled the baseball world

Fifty years ago this month, Denny McLain did something that hadn’t been done in 34 seasons and hasn’t been accomplished since.

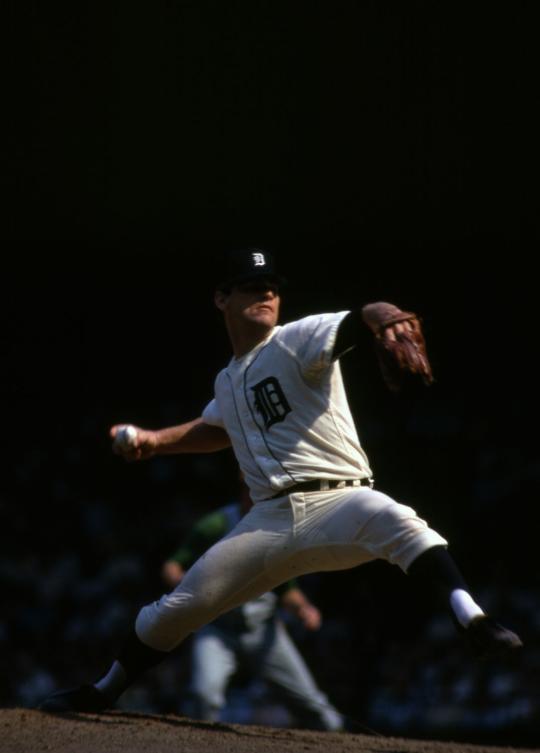

It was “The Year of the Pitcher” and McLain, the young and brash right-handed hurler with the Detroit Tigers, was on the precipice of immortality as he approached his 30th win of the 1968 regular season.

The last big leaguer to reach the coveted mound milestone was Dizzy Dean, a “Gashouse Gang” legend with the Cardinals when he finished with a 30-7 won-loss record in 1934. You have to go back to 1931 with Lefty Grove to find the previous American League 30-game winner, the Philadelphia Athletics southpaw finishing that stellar campaign with a 31-4 mark.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Sporting a 29-5 record and with only two weeks left in the ’68 regular season, the 5-foot-11, 190-pound McLain, in only his fourth full season, had the starting nod against the visiting Oakland Athletics on the balmy afternoon of Saturday, Sept. 14, at Tiger Stadium.

Not only were there 44,087 fans in the stands – including McLain’s wife Sharyn (the daughter of Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau), his widowed mother Betty, brother Tim and 3-year-old daughter Kristi – but an estimated 30 million watched the nationally televised “Game of the Week” broadcast on NBC-TV with Curt Gowdy doing play-by-play and Pee Wee Reese and Sandy Koufax serving as color commentators.

Even the opposing starting pitcher was getting some good-humored attention, with Oakland backup catcher Jim Pagliaroni before the game sporting a homemade sign hanging from his neck that read, “Chuck Dobson Goes for No. 12 Today.”

The outlook, though, looked dire for McLain with Detroit down 4-3 in the bottom of the ninth. The 24-year-old had pitched admirably, tossing 114 pitches over nine innings while giving up four earned runs on six hits and a walk while striking out 10 before departing for a pinch-hitter – Al Kaline – to lead off the bottom of the ninth.

The dramatic comeback – in a game that took exactly three hours to complete – began with a Kaline walk and a Mickey Stanley single that put runners on first and third before a Jim Northrup fielder’s choice tied the game. With the home crowd cheering wildly, local favorite Willie Horton drove a 2-2 pitch off losing pitcher Diego Segui over the head of drawn-in left fielder Jim Gosger’s head for a walk-off single that gave the Tigers a 5-4 win. For McLain, his historic 30th victory of the year was also his 27th complete game in 38 starts.

“I was confident going in today, although about the fifth inning I felt it just a bit. I’m not the type to stand out there and worry, though, and my idea was just to keep us close until this club could explode. We always do,” said McLain after the game. “This club does things that way; they’ve been doing it all year. When Al got on in the ninth, I knew we could do it. I always think we’re going to win, but I figured that maybe the string had run out when we failed to put across any scores in the eighth. Then Al did it.

“It really built up right from the beginning of the game. There was a great amount just trying to keep us close after we fell behind. But you probably could feel it too. The people out there went crazy when we won it, and so did I. No, I didn’t think we were going to lose. I always think I’m going to win. And when we came to bat in the ninth I half expected it, especially the way this club is.”

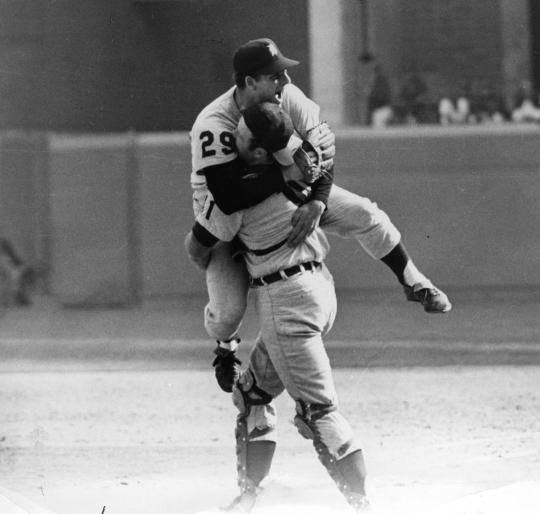

Kaline, the future Hall of Famer whose walk started the ninth-inning rally, said, “I was sitting next to Denny on the bench when Horton hit it. He jumped up like he didn’t believe it and raced out there to get to Horton.”

Soon after Horton’s game-winning hit fell safe, Tigers teammates lifted McLain – who had already beaten the A’s three times that season – and carried him to their third-base dugout. Then excited fans could be heard chanting, “We want Denny!” before the man of the hour was brought out onto the field to receive a standing ovation from the crowd.

“I was up for this one. Getting to 30 is passing a hump. Yet all the time I was going through this excitement, I really was more sincerely concerned about the Tigers winning the pennant than my reaching 30 victories,” said McLain after the Tigers’ magic number to clinch the AL pennant for the first time since 1945 was reduced to four games with the win.

Tigers catcher Bill Freehan lifts pitcher Mickey Lolich into the air following the final out of Game 7 of the 1968 World Series. Lolich won three games during that World Series, but Denny McLain's clutch performance in Game 6 set the stage for the decisive Game 7. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“I hope we clinch the pennant here at home. These fans deserve it. Today I could feel the people with me on every pitch. We’ll draw more than two million fans at Tiger Stadium this season and they should be rewarded by seeing us win the clincher at home. You think today was exciting! Wait’ll the day we win the clincher. Then you’ll see a real celebration.”

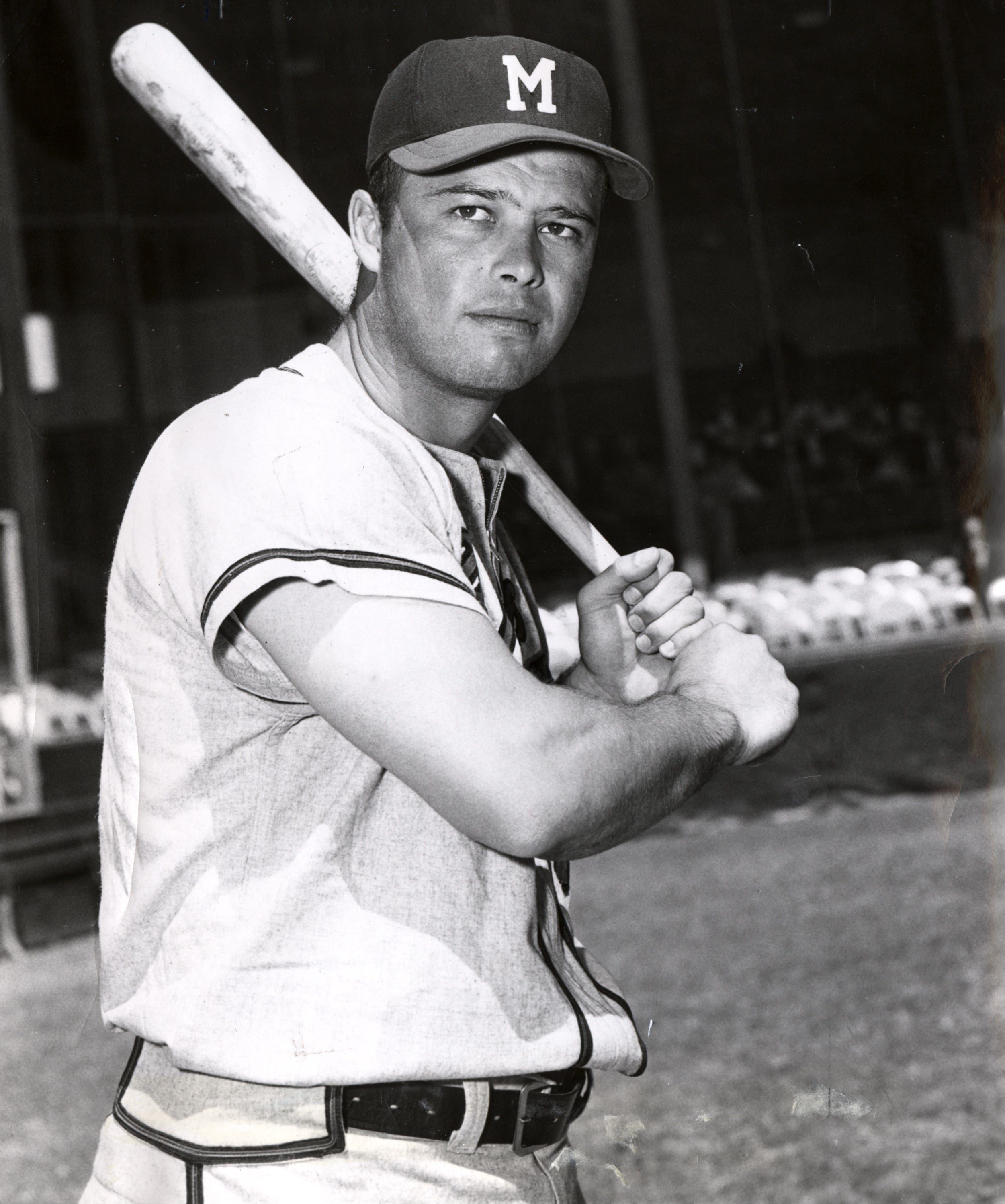

Twenty-two-year-old Reggie Jackson, a future Hall of Famer, shined in defeat for Oakland, clubbing two homers - his 27th and 28th of the season - into the right-field stands as well as throwing a runner out at the plate from right field.

“That was the change-up that Reggie Jackson hit for his second homer. His first home run came on one of my good curveballs – he was just waiting for it,” McLain said. “It was a good curve ball that Jackson hit and I shouted at (A’s first baseman Danny) Cater that Jackson had better look for that damn thing again because he sure was gonna get it. I struck him out with the same pitch in the ninth.”

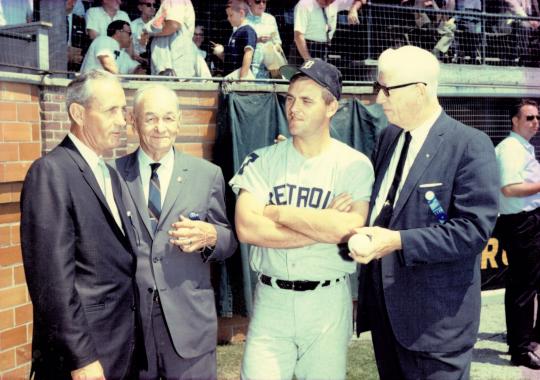

Dean, who attended the game clad in his signature cowboy hat, was asked what he said to McLain in a pregame talk. “I told him that it was just another ballgame and that winning No. 30 wasn’t any tougher than winning No. 1. They’re all tough and they all count.”

“They won’t have this much excitement here if they win the World Series,” added Dean, who traveled 1,400 miles from his home in Wiggins, Miss. to be at the game. “I wanted him to win today. But after seeing this kid, I wonder why they called me Dizzy.”

Contacted by the Boston Globe, the 68-year-old Grove said he watched McLain’s 30th win on television.

“McLain’s a great pitcher,” said Grove from his son’s home in Norwalk, Ohio. “I got a kick out of seeing him win.”

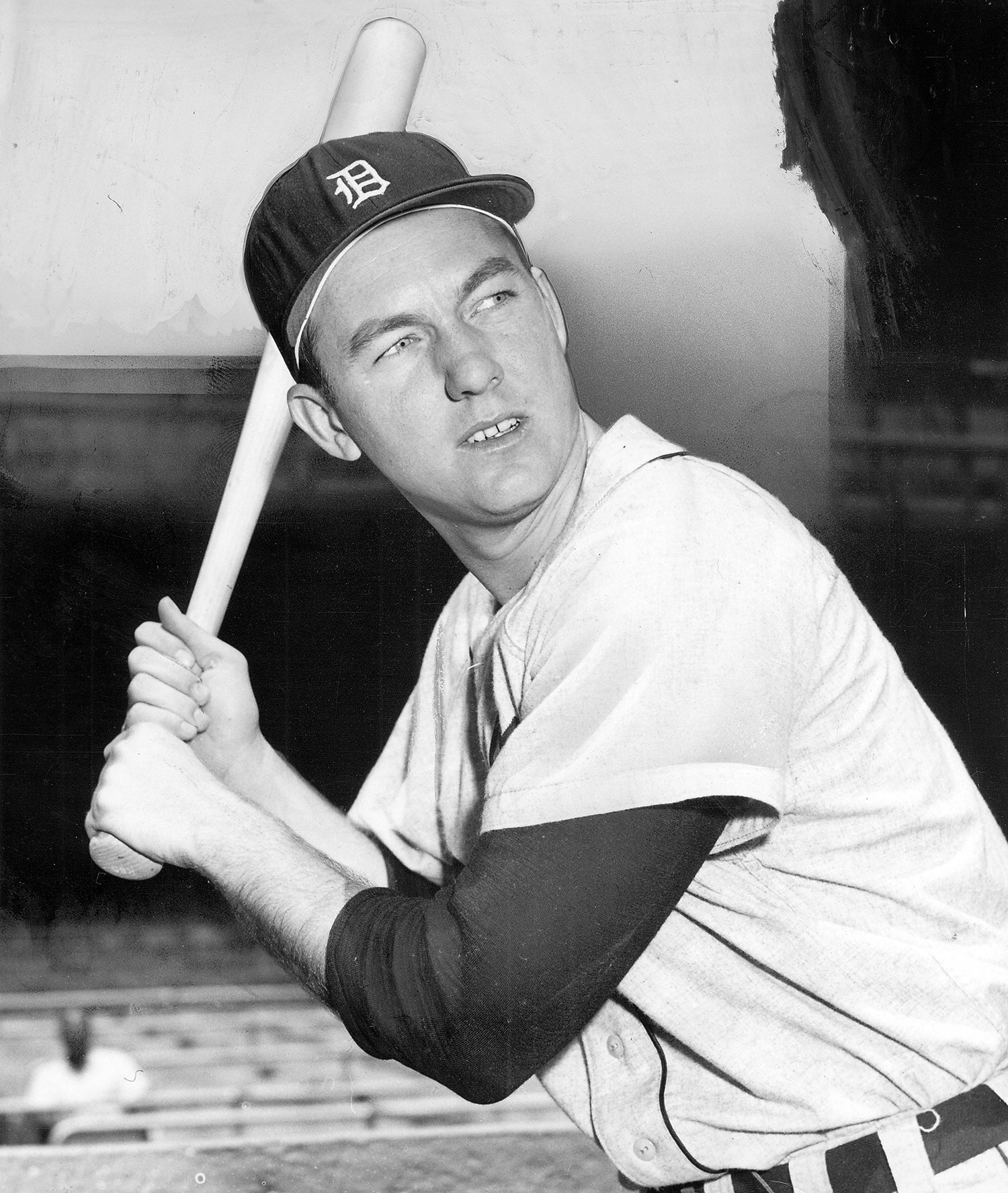

According to McLain’s Detroit teammate Eddie Mathews, the future Hall of Famer had seen many great pitchers during his career, “But I’ve never seen any pitcher who does it as effortless as this man. Believe me, he’s going to be one of the real great ones.”

What began as “Mickey Lolich Day,” on official dedication by the Croatian Club of Detroit for a fellow Tigers pitcher, changed at 5:30 p.m. when Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanagh made the proclamation that it was now “Denny McLain Day.”

“Well, I’m congenial, I’m honest, I’m mild-mannered. I’ve got a good sense of humor, nothing hardly ever bothers me, and I’m a fun lover,” said McLain in a September 1968 issue of LIFE magazine. “My idols are Frank Sinatra and Arnold Palmer. I like the way they’ve made their fortunes. They worked for it. I like the way they live. They’ve got security. They’re independent. Sinatra doesn’t give a damn about anything and neither do I.”

Tigers manager Mayo Smith would later explain handling an extrovert like McLain.

“You don’t deal with a type of personality like Denny’s. This is a 24-year-old boy reaching for Utopia. You accept what he is and work with that,” said Smith. “Oh, you still talk to him about some of the things he does. I talk to him probably more than anyone about keeping things toned down. But this is what makes him a great pitcher – a great pitcher. He’s brash enough. You can’t take that brashness away from him and you wouldn’t want to. I like him for what he is.

“This is his secret – a new pitch, concentration and control of himself. Last year he couldn’t throw a slider. But in Spring Training the second day in camp, all of a sudden he got it. As for concentration, I couldn’t do that for him. John Sain (pitching coach) couldn’t do that for him. He did that himself,” Smith added. “That’s why I say Denny has grown up a lot since last year. He has learned to keep his emotions better under control. There have been times he could have blown his top in a tough situation. But he hasn’t.”

McLain – whose pitching repertoire at the time included a fastball and curve from overhand, three-quarter and sidearm deliveries – admitted it took him some time to master the slider. “Some guys learn it in two weeks. It took me a year.”

“Denny has always known what he can do with the baseball,” said Sain in a July 1968 issue of Sports Illustrated. “Now he has learned the technique of doing it correctly. He knows when to throw a rising fastball instead of a sinking fastball, when to throw a change-up instead of a curve. He knows a lot more about what he is doing than the 30,000 people in the ballpark think he does.”

Besides the personal acclaim that came with his mound success – appearing on the covers of Time and Sports Illustrated during this period - there was a financial component that accompanied it that McLain was well aware of.

“When Denny reaches 30, then we’re ready to really move,” said Frank Scott, a talent agent from New York who handled Don Larsen after his perfect game in the 1956 World Series, Mickey Mantle when he won the Triple Crown in 1956 and Roger Maris after his 61 homers in 1961. “We have eight to 10 deals already, but 20 or so are waiting on his winning 30. Thirty will bring in 25 percent more than 29.

“The most earned by a ballplayer in outside income was $200,000 by Roger Maris in 1962, the year after he hit 61 homers,” revealed Scott, who estimated that McLain, who was also a professional organist, might earn at least $100,000 in television appearances and endorsements during the winter. “Where a Mantle or a Maris could command only $1,000 or $1,500 an appearance because they were limited to saying a few words, McLain can play the organ and ask for and get $2,500.”

Legendary Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio, then a coach with Oakland, explained the financial aspect of baseball popularity. “People always are willing to pay to see a baseball star. A World Series hero can get between $500 and $2,000 for an appearance. All he needs to do is show up at the cocktail party, shake a few hands, go to the banquet, accept an award, and tell a few old jokes.

“But McLain has a great plus for himself. He is a master at the organ console. He can go into nightclubs in Las Vegas, Miami Beach, Chicago, and along the way, and give a great act. He can play his own fanfare. People who wouldn’t pay a nickel to see McLain, who wouldn’t give a penny for his autograph, will love him at the organ.”

Offseason plans for the Denny McLain Quintet included an appearance on the Ed Sullivan TV show as well as bookings around the country. Also around this time, the Hammond Organ Co. had introduced a new model in New York City and selected McLain, among others, to play the instrument.

There were also reports at the time that McLain would be asking for a $100,000 salary from the Tigers in 1969 after his 30-win season. “Well, after today I’m in a better bargaining position. But I don’t like to ask. I just wish the Tigers would make an announcement. Like real soon.”

McLain, whose Tigers would go on to capture the 1968 World Series in seven games over the Cardinals, would in the offseason be named unanimous winners of both the American League’s Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards. In a remarkable campaign, he went 31-6, starting 41 games and completing 28, tossed six shutouts, struck out 280 batters in 336 innings, and finished with a 1.96 ERA. The Tigers workhorse led the Junior Circuit that year in wins (31), winning percentage (.838), games started (41), complete games (28) and innings pitched (336).

If not for arm troubles and off-the-field issues derailing his promising career, McLain may have had a bronze plaque in Cooperstown. But there are artifacts from his 30th win of the ’68 season at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including the fielder’s glove he wore that afternoon and a baseball used in the game.

McLain would end a 10-season career (1963-72), eight spent with the Tigers, with a 131-91 record, a 3.39 ERA and 1,282 strikeouts in 1,886 innings. He won 16 or more games five years in a row, from 1965 to ’69, and won 20 or more games three times. A three-time All-Star, he topped Cy Young Award voting twice, winning in 1968 and sharing the honor with Baltimore’s Mike Cuellar in 1969.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum