- Home

- Our Stories

- Buffalo baseball has Hall of Fame legacy

Buffalo baseball has Hall of Fame legacy

Due to an insidious virus, Buffalo is now an integral part of a bumpy 2020 big league baseball season. But 140 years ago, the “Queen City,” in the nascent days of the National League, hosted a squad with four exceptional players who would one day have bronze plaques in Cooperstown.

Stars Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Bo Bichette and Nate Pearson are now calling Buffalo home after their team, the Toronto Blue Jays, were compelled by the Canadian government to find a new address for fear of spreading COVID-19 among its populace.

In this pandemic-shortened 60-game season, the Blue Jays’ home games take place at Sahlen Field, the home ballpark of Toronto's Triple-A affiliate since 2013. Buffalo hosted its first game – with no fans in attendance – on Aug. 11, the first time the city hosted a major league game in more than 100 years.

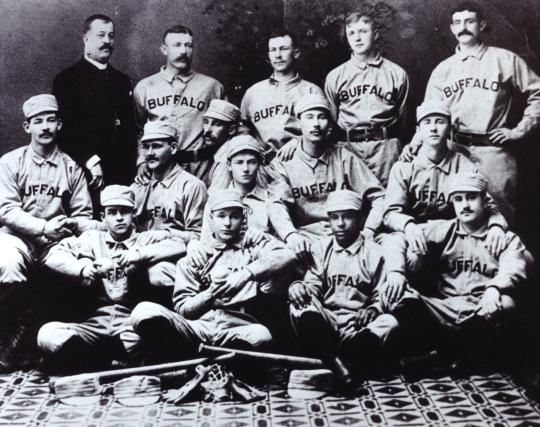

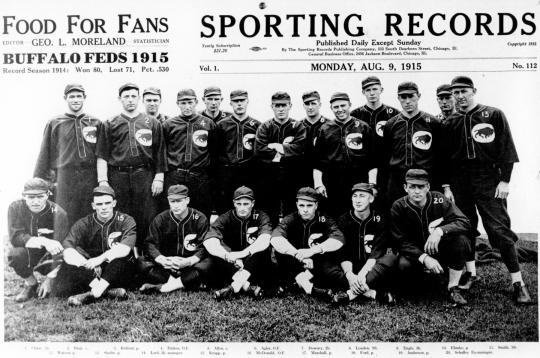

Buffalo’s previous taste of big league ball came more than a century ago, first as a member of the National League from 1879 to 1885, then a single season in 1890 with the Players League, and, lastly, as a part of the Federal League from 1914-15.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

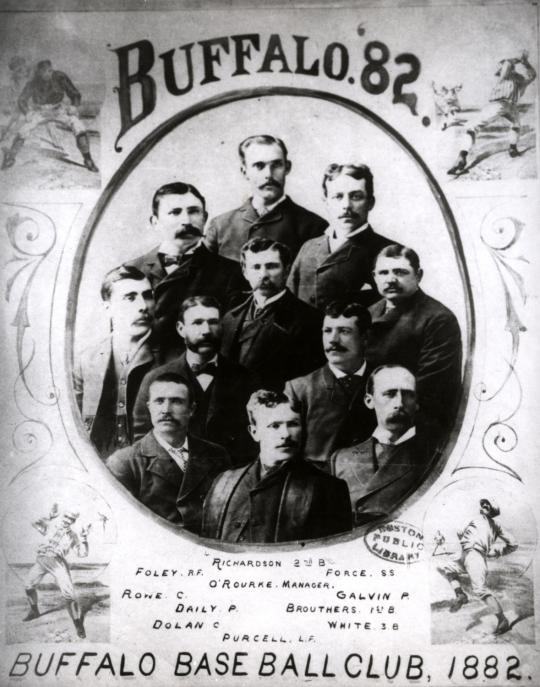

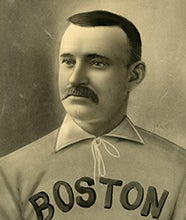

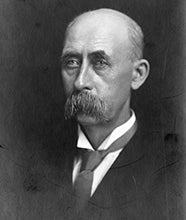

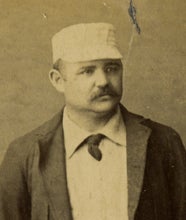

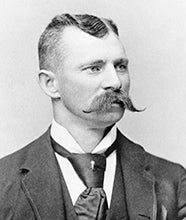

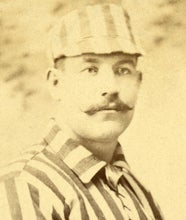

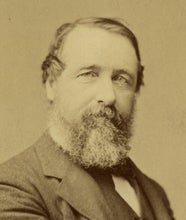

It was during the early days of the National League – a loop that began play in 1876 – that during a four-year period from 1881 to 1884, a team most commonly referred to today as the Buffalo Bisons had on its roster four future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Outfielder/first baseman/third baseman Deacon White (Class of 2013), third baseman/outfielder Jim O’Rourke (Class of 1945), first baseman/outfielder Dan Brouthers (Class of 1945) and pitcher Pud Galvin (Class of 1965).

Amazingly, despite the fact that the Bisons were a star-laden squad and had winning seasons every season from 1881-84 while compiling an overall mark of 206-169, the team never finished above third place in an eight-team NL. But their perceived underachievement can’t be thrust upon the four Hall of Famers, who all put up tremendous numbers during this period.

“They’re all in the Hall of Fame and in large part – and I know they had good careers elsewhere – for what they did right here in Buffalo,” said Buffalo baseball historian Brian Frank. “And it’s amazing how quickly it all fell apart.

“In 1885, Galvin wasn’t pitching that well and they ended up selling him to Pittsburgh in July. O’Rourke had left the year before. Since they weren’t winning games, their attendance dropped off. Their owner at the time seemed like he was done with baseball, so he ended up selling the franchise and all its players to Detroit in September. So that was the end of it for Buffalo in the National League. They lost 16 in a row to end that 1885 season.”

Among the artifacts in the permanent collection of the Baseball Hall of Fame from this unique era of Buffalo baseball history are a half-dozen scorecards from games between 1881 and 1884, a pair of bats and medals once belonging to Brouthers and a medal presented to O’Rourke.

Brouthers, a mighty slugger and all-round player, had a keen eye and tremendous power at the plate. Arguably the first left-handed batter to gain prominence in the game, the renowned cleanup hitter led the NL in batting average four times – including with Buffalo in 1882 (.368) and 1883 (.374) – home runs twice and runs batted in twice, and finished his career with a .342 batting average.

There’s even one legendary story of Brouthers being chased around the bases after a homer by an unhappy pitcher, the hurler reportedly screaming, “You big bully. You ought to be ashamed of yourself going around the country with a telegraph pole for a bat and knocking the bread and butter out of pitchers’ mouths.”

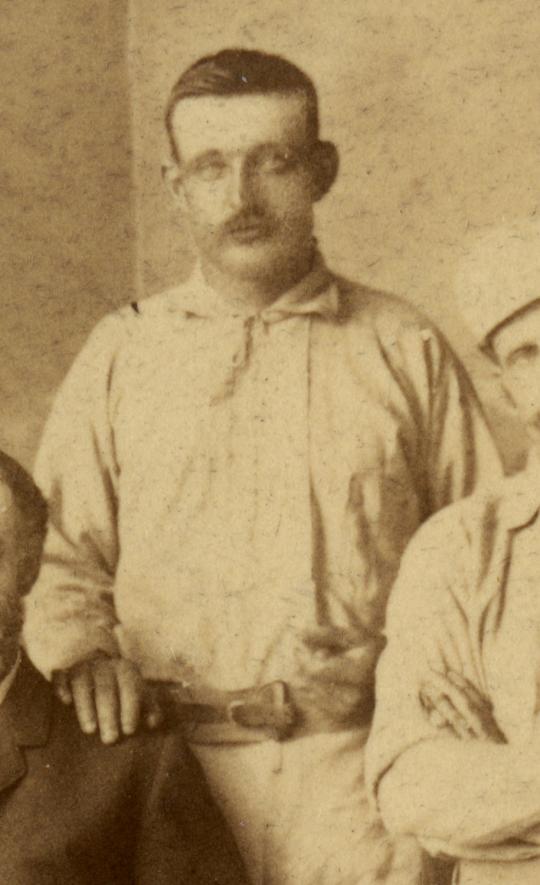

James “Pud” Galvin, though only 5-foot-8, was a peerless pitcher who was recognized as the hardest tosser of his day. Also known as “Gentle Jeems” and the “Little Steam Engine,” Galvin won 365 career games. His greatest success came with Buffalo, where, when teams had only two-man rotations and little relief help, he was victorious 218 times, including back-to-back 46-win seasons in 1883 and 1884.

“Galvin was the most popular player on the Buffalo team,” said onetime Bisons catcher Jack Rowe. “He never seemed to tire and was always anxious to go in. In fact, teams did not carry the number of twirlers they do today so that one man did the bulk of the pitching, being relieved when a team came along that another twirler was thought good enough to hold down.”

O’Rourke was one of the most notable figures in baseball when he arrived in Buffalo in 1881 to serve as player-manager. Nicknamed “Orator Jim” because of his extensive vocabulary – reportedly even using words with six syllables – the heavy hitter would go on to a 23-year big league playing career that included a NL-best .347 batting average in 1884.

Asked why he was able to play in the big leagues for almost two dozen season while contemporaries could not, O’Rourke said, “The reason is that they did not lead a clean life as I did. I never touched a drop of liquor in any form, nor did I ever use tobacco. I always took care of myself. That’s the reason why I went along while the other fellows hit the road which has no return route.”

White, who learned the game from a Union soldier back from the Civil War in 1865, was an acclaimed barehanded catcher in the 1870s before arriving in Buffalo in 1881. A powerful hitter, he won two batting titles in a 20-year career that ended with a .312 overall average, including a .301 mark during a five-year stint with Buffalo.

“What we most admired about White was his quiet, effective way,” said Hall of Fame pioneering journalist Henry Chadwick. “Kicking is unknown to him. And there is one thing in which White stands preeminent, and that is the integrity of his character. Not even a whisper of suspicion has ever been heard about Jim White. Herein lies as much of his value to his team as his great skills.”

Amazingly, Hall of Fame pitcher Old Hoss Radbourn, who would go on to win 310 major league games, including 60 for the NL’s Providence Grays in 1884, made his big league debut with Buffalo in 1880, but the only six games he played with the Bisons that season were split between second base and right field. He would be released in May 1880, reportedly due to his sore pitching arm.

“Buffalo had good teams during that time with four third-place finishes and the four future Hall of Famers playing for them. And they were a successful franchise until that 1885 season when things fell apart,” Frank said. “But the big thing to me was those four Hall of Famers were all really in their prime at that time. It’s amazing. None were youngsters and none were veterans just hanging on. They were all stars and played like it and are in the Hall of Fame because of it.

“I think with the Blue Jays playing here now, local baseball fans are now realizing there was a National League team that played in Buffalo. But if you asked people a month ago, your average fans wouldn’t have been aware.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum