- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Fred Norman

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Fred Norman

The process of coming up with a theme for Card Corner is sometimes less than scientific. In fact, it might be called downright bizarre, as it is with this one. In recent weeks, I’ve been watching the entertaining show, Bates Motel, in reruns on Netflix. One of the central characters to the show is the infamous Norman Bates, who was originally played by Anthony Perkins in the 1960 Hitchcock classic, Psycho. In the Bates Motel rendition, the younger version of Bates is played by talented British actor Freddie Highmore. Once you blend the first name of the actor with the first name of the character, you come up with the name, “Fred Norman,” or “Fredie Norman.” And that leads us to this selection from the 1973 Topps set.

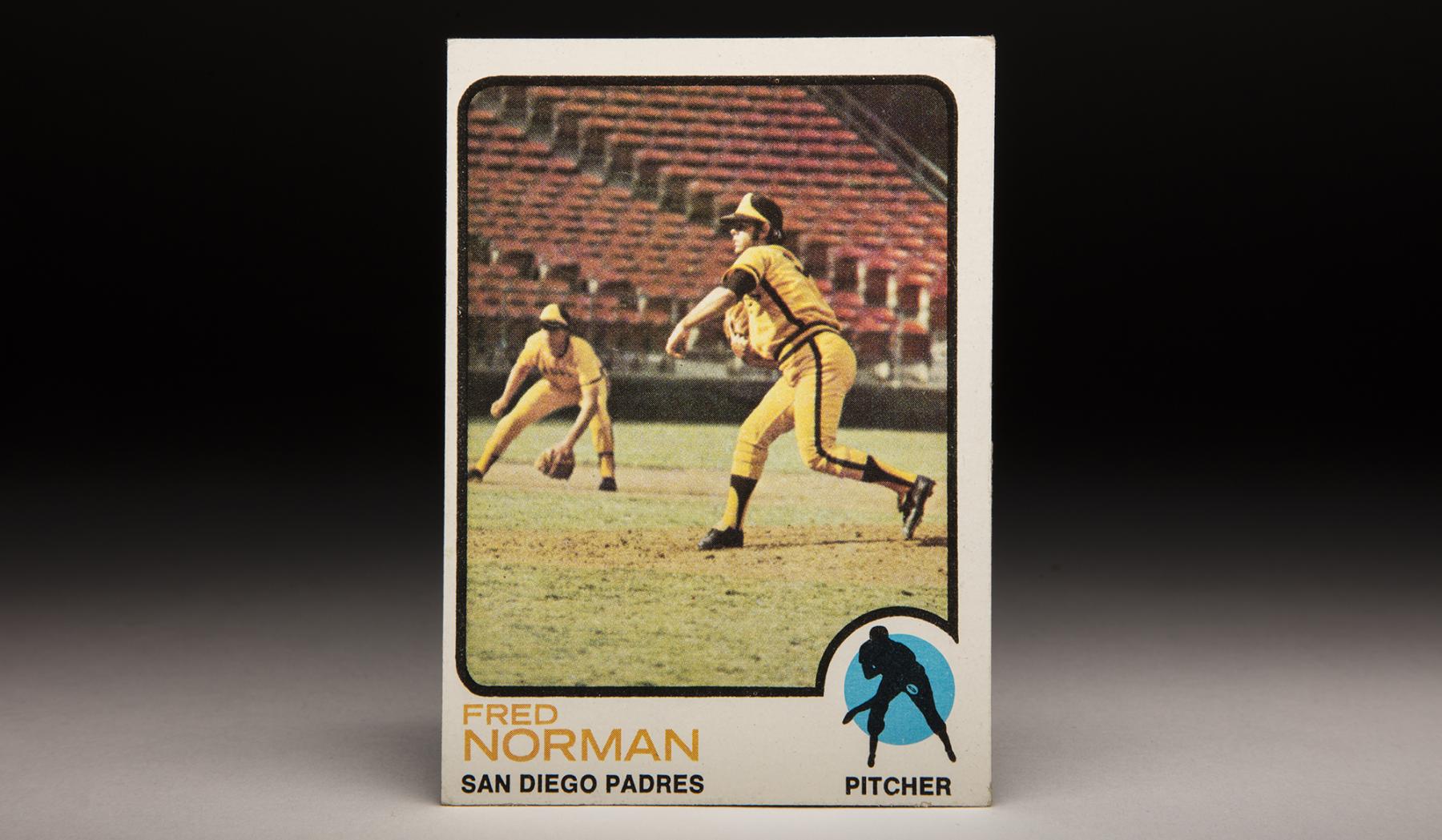

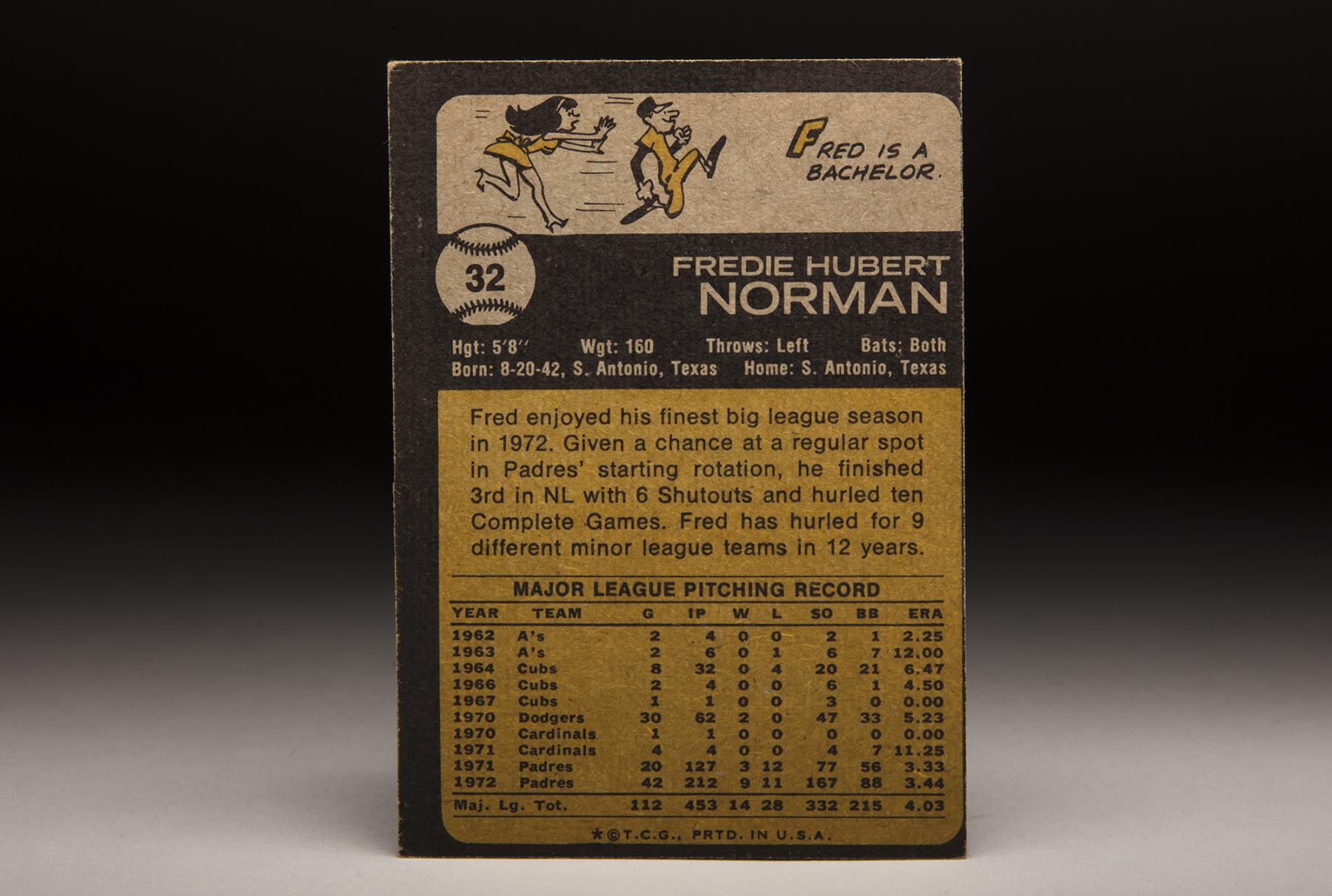

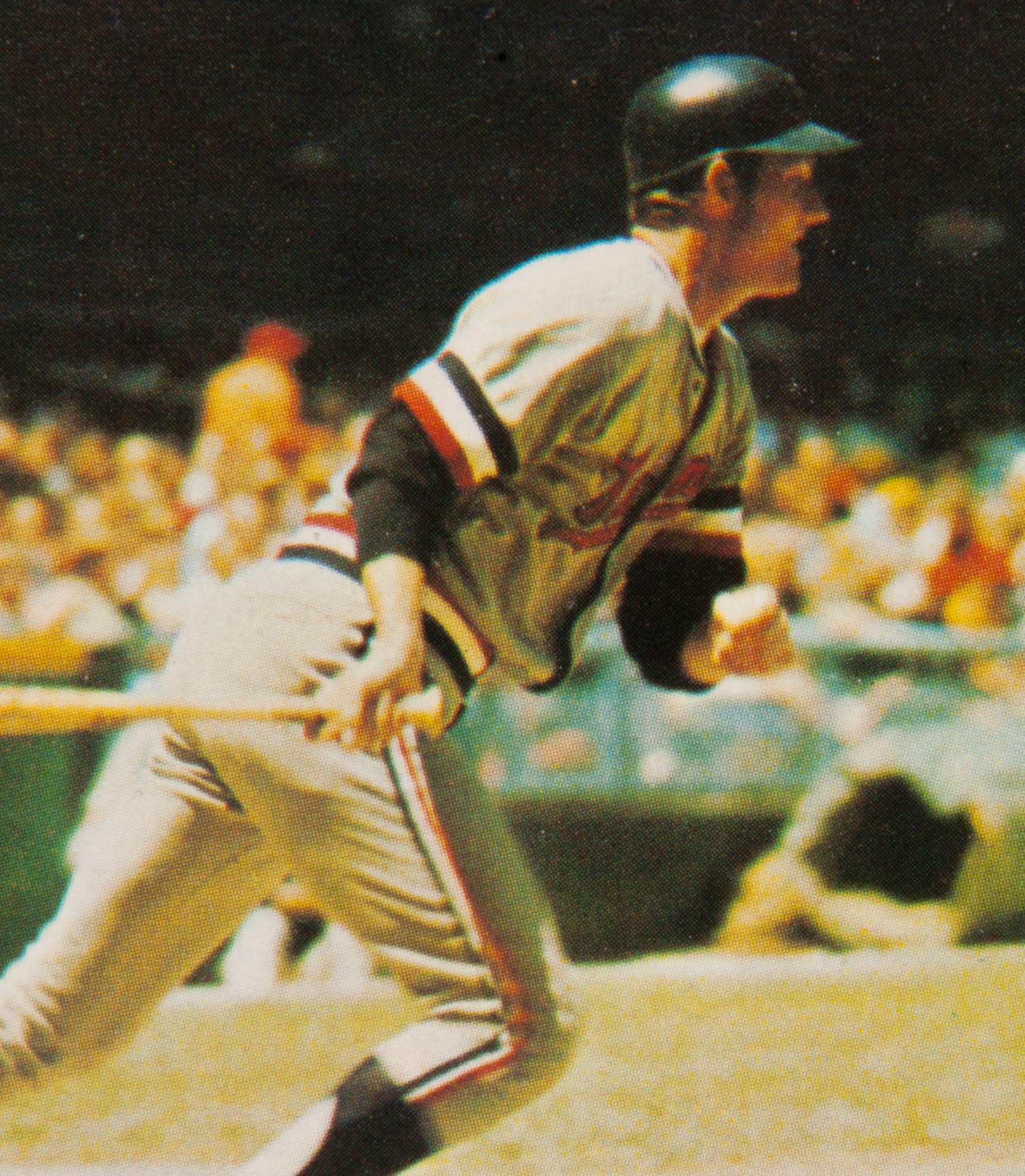

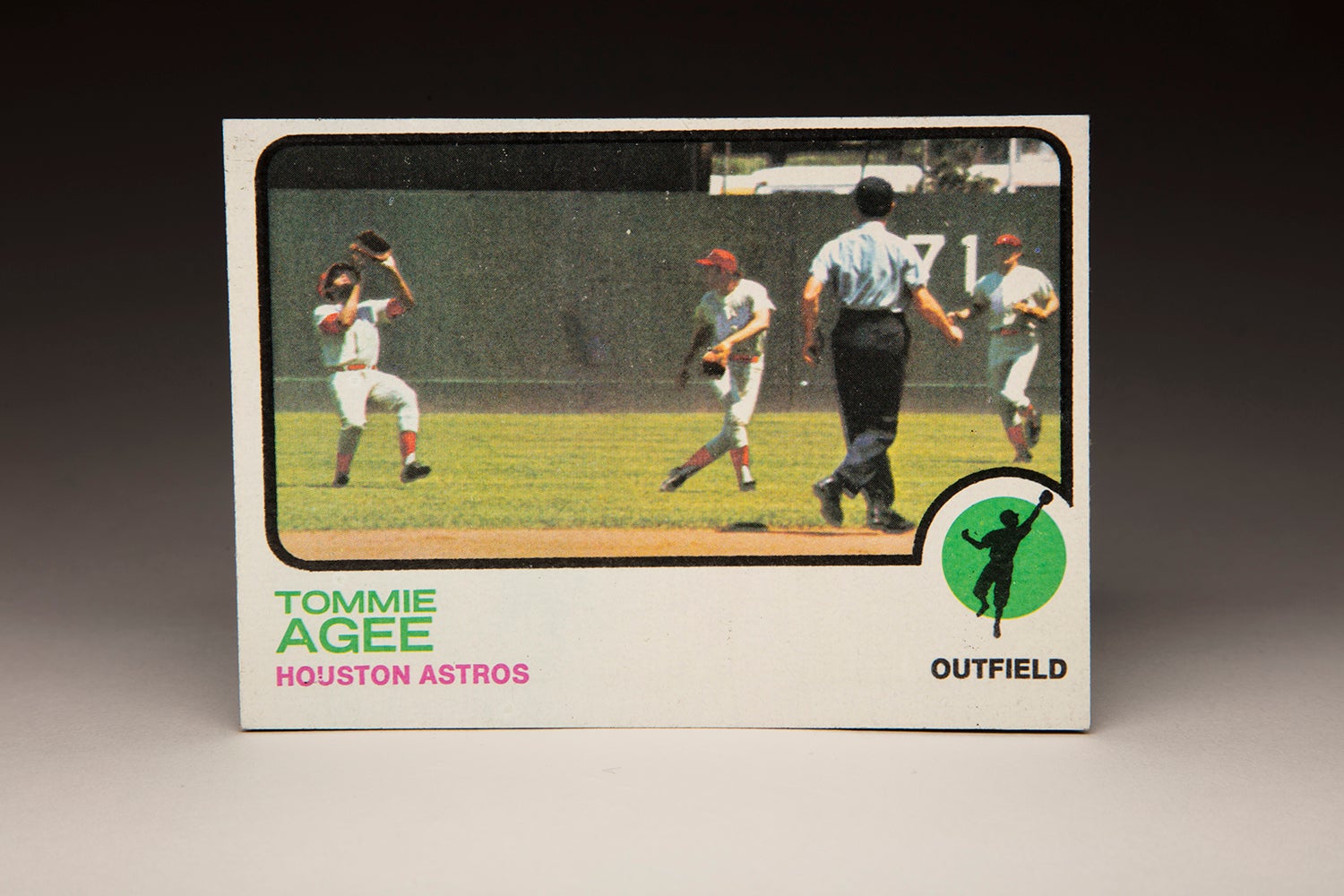

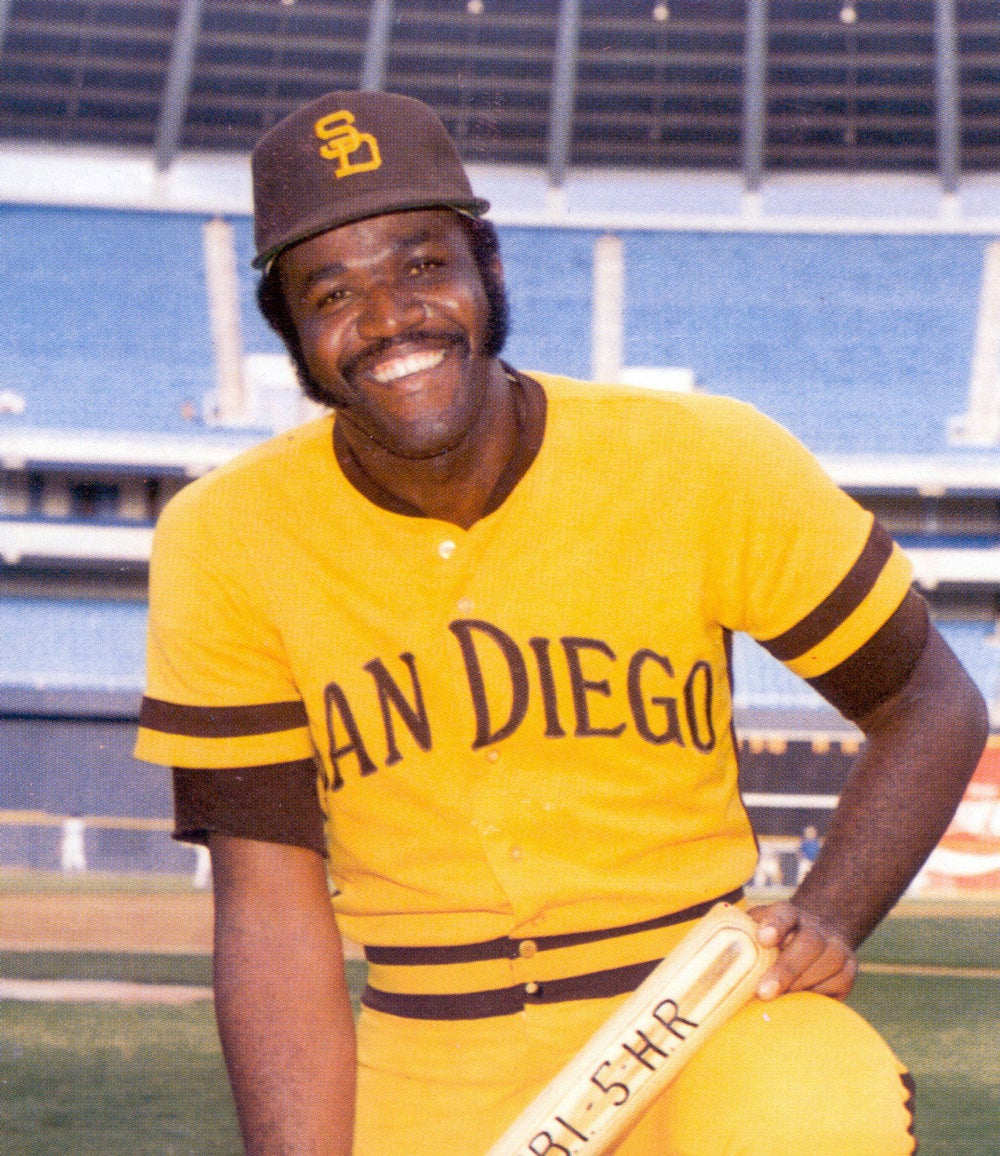

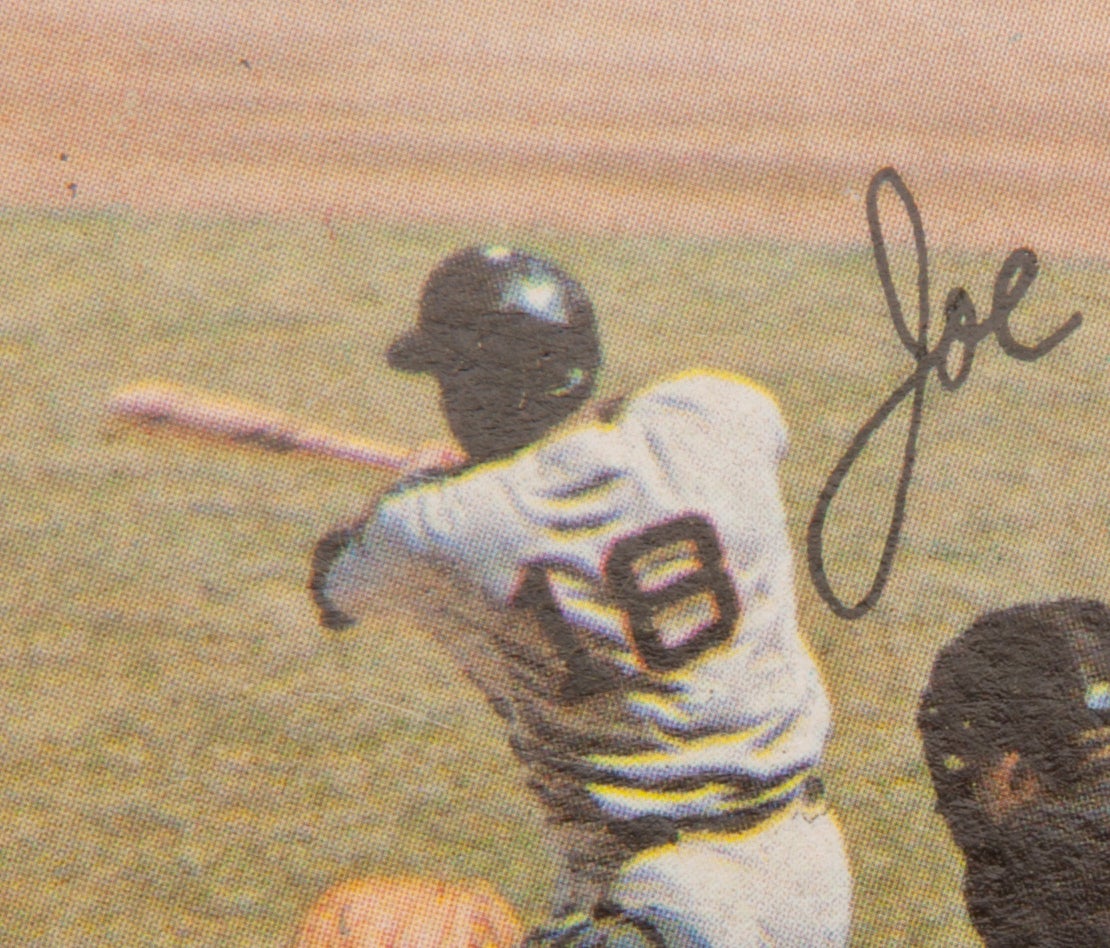

The Norman Bates connection is just one of many factors behind my interest in the Fred Norman card. The card itself contains several noteworthy features. Let’s begin with those memorable yellow-and-brown uniforms worn by the San Diego Padres in 1972, when this photograph of Norman was taken. The color yellow is fine when blended with other colors, but when yellow becomes the dominant color of a uniform, covering both the jersey and the pants on a team’s uniform, it is a little bit much. And when complemented by brown as the trim color, the end result is something that is gaudy to the extreme.

Second, the Padres of the early 1970s did not draw particularly well. No, those aren’t fans dressed in all-red outfits on the Norman card; those are rows and rows of empty seats along the left field line at old San Diego Stadium. In fact, every seat in this photograph is empty; there isn’t a fan to be found anywhere on this card. The Padres drew scant crowds in 1972, attracting only 644,000 fans over the course of the entire season. Those fans who did turn out saw a last-place team that won only 58 games while losing 95. Other than Nate Colbert and LeRon Lee, the ’72 Padres didn’t hit very much. And outside of Norman, Clay Kirby and Steve Arlin, the pitching staff did not make up for the offense’s shortcomings.

Norman’s card is also notable because of the presence of one of his teammates in the background. Given the angle from which the photographer took this shot, it appears that the player is the Padres’ third baseman. Based on the frequency of games played, the best bet is that it is Dave Roberts, a versatile player who played more games at third than anyone on the Padres’ roster in ’72. If it’s not Roberts, it might be the late Dave Hilton, who was taken in the first round of the January 1971 draft. Two other possibilities are Dave “Soup” Campbell, who would later go on to a successful career as a broadcaster at ESPN; or Fred “Chicken” Stanley, the future utility infielder for the New York Yankees. But it doesn’t look like Soup or Chicken to me. I’ll stick with Mr. Roberts as my guess.

There’s one other piece of intrigue with the Norman card. It has to do with Norman’s right foot, or the foot that he led with during his delivery. The foot, covered in a dark brown Padres shoe, appears to be cut off in the middle. The toes look to be missing from that foot, as if Norman had some kind of disfigurement, reminiscent of the long-ago NFL placekicker, Tom Dempsey. Yet, I have no recollection of Norman having any problem at all with his foot. Perhaps this is simply an imperfection in the photograph, but for now the mystery of the odd foot will have to remain unanswered.

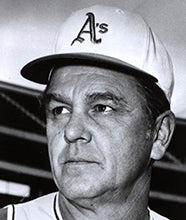

More pertinent to the discussion is Norman’s left arm, and the resilience that he showed during a career that could have ended all too soon. As an amateur pitcher in Florida, Norman threw an electric fastball which belied his diminutive 5-foot-8, 155-pound stature. At the time, major league scouts didn’t seem to care as much about a pitcher’s height as they do in today’s game, so Norman became the target of several teams. One of them was the Kansas City Athletics, run by their aggressive new owner, Charlie Finley.

With Finley leading the charge, the A’s signed Norman to a contract, including a large bonus in the range of $40,000 to $60,000. The A’s liked Norman enough that they assigned the first-year pro to the Double-A Southern Association. As much talent as he possessed, young Norman still had a little too much Bates in him; more specifically, he was far too wild. In 53 innings, he walked 64 batters, which helps explain why his ERA rose all the way to 5.70.

Realizing that Norman needed to be brought along more slowly, the A’s sent him down to Lewiston of the Class B Northwestern League in 1962. He pitched reasonably well there and received a call-up to Binghamton of the Eastern League. After a stint in Binghamton, where he posted mediocre numbers, the pitching-needy A’s rushed him up to the major leagues before season’s end.

The following summer, Norman went back to Double-A ball, where he started to turn the corner. Norman set an Eastern League record by striking out 258 batters for Binghamton. After dominating Eastern League hitters, the A’s again chose to have him bypass Triple-A and head right back to Kansas City. Once again, Norman wasn’t ready; he posted an ERA of 11.37 in two nightmarish late-season appearances.

After that season, the A’s traded Norman that winter, sending him to the Chicago Cubs for outfielder Nelson Matthews. Rather than have Norman receive some seasoning at Triple-A, the Cubs opted to put him on their Opening Day roster. Norman made five starts and three relief appearances, flopping in both roles. With a record of 0-4 and an ERA of 6.54, it was obvious that Norman needed more time in the minor leagues.

Over the next season and a half, Norman struggled with his control in the minors. Then came a breakthrough in 1966 while toiling for Double-A Dallas-Ft. Worth in the Texas League. Norman pitched brilliantly, forging an ERA of 2.73 and winning 12 games. The Cubs rewarded him with a late-season recall to Chicago. In 1967, Norman made the Cubs’ Opening Day roster, but he was used infrequently by manager Leo Durocher. “I was just there, the 10th pitcher,” Norman said years later in an interview with Sports Collectors Digest.

Norman recalled a game where he pitched extremely well in relief, but remained an afterthought in the bullpen. “I pitched one inning and struck out [Willie] Stargell, [Donn] Clendenon and [Roberto] Clemente, but I guess that wasn’t enough.” Norman felt that Durocher didn’t care for him. As it turned out, another National League team took a strong liking to Norman. In mid-1967, the Los Angeles Dodgers acquired the left-hander in a one-for-one trade for right-hander Dick Calmus.

The Dodgers immediately assigned Norman to Spokane of the Pacific Coast League, where they started him every fourth day. Unfortunately, Norman soon hurt his left shoulder. The injury did permanent harm, reducing his velocity. Realizing that Norman was no longer a power pitcher, the Dodgers worked with him on his control and his refinement of his breaking pitches. They also altered his pitching mechanics.

Despite the oversight from his coaches, Norman returned to the disabled list in 1968. Norman eventually returned to pitch for Albuquerque, the Dodgers’ top affiliate in the PCL. The team’s manager, Roger Craig, put in some serious work with Norman, principally teaching him to throw a slider. The sessions with Craig paid off in 1970, when the Dodgers finally promoted Norman to the major league roster.

Still, positive major league results eluded Norman. He appeared in 30 games as a reliever, posting a bloated ERA of 5.23. By September, the Dodgers gave up on Norman. They placed him on waivers, allowing the St. Louis Cardinals to claim him for a small fee. Although the transaction was officially described as a waiver claim, Norman believes the Dodgers arranged for him to go to St. Louis as part of a future trade that would be announced just a few days after the season; that blockbuster deal would send slugger Richie Allen to the Dodgers for second baseman Ted Sizemore and catcher Bob Stinson. “I found out I was the third guy in that trade,” Norman told Sports Collectors Digest.

In 1971, Norman made the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster, but he pitched poorly out of the bullpen and soon returned to the minor leagues. At this point, no one could have blamed Norman for giving up. He was 28 – and headed on the fast track toward oblivion.

At Triple-A Tulsa, Norman encountered a new manager: Hall of Famer Warren Spahn. Norman paid heed to Spahn, who showed him the proper way to throw a screwball. It was the pitch that would change Norman’s career, finally allowing him to take a toehold in the major leagues. Spahn also worked with Norman on both the physical and mental aspects of the game. “He taught me the mechanics and psychology of pitching, after all those years,” Norman said years later in an interview with Baseball Digest.

The Cardinals themselves would not see the benefit of Spahn’s work. In June, the Cards traded Norman and outfielder LeRon Lee to the expansion Padres for right-hander Al Santorini. With that trade, Norman’s days in the minor leagues had come to a complete stop.

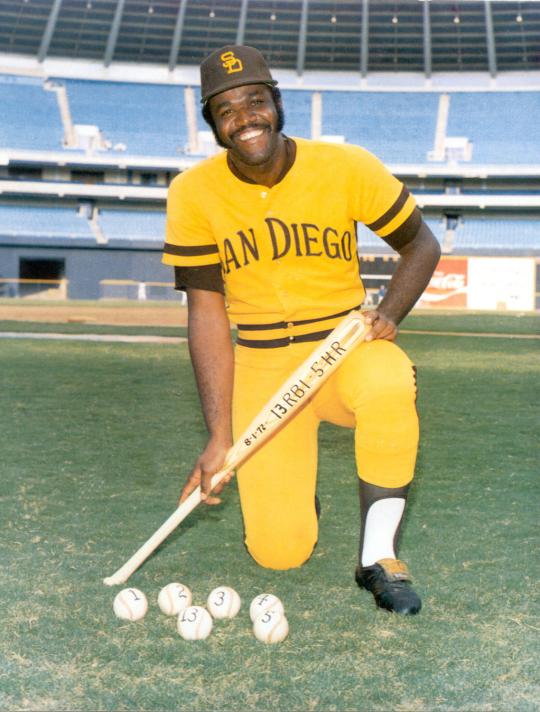

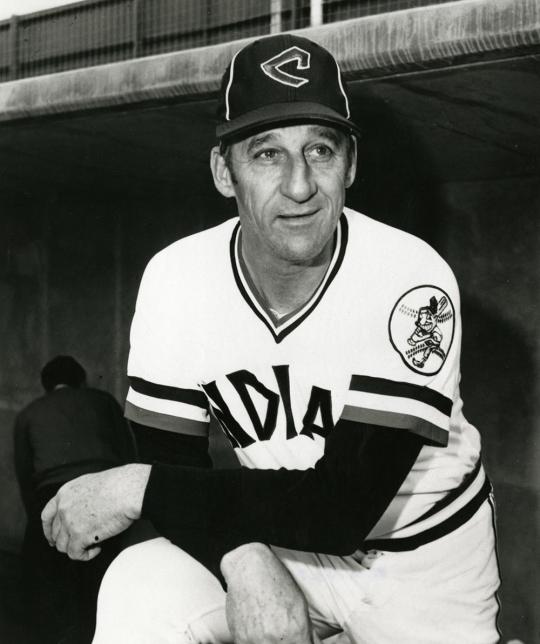

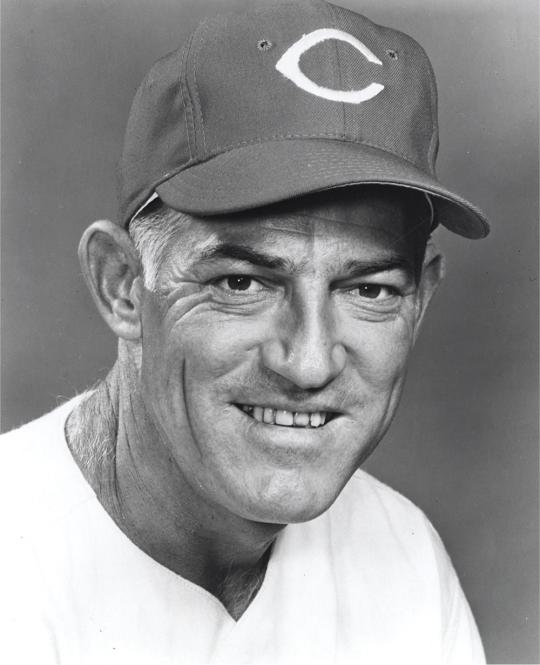

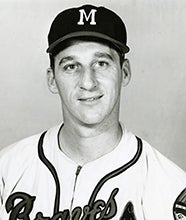

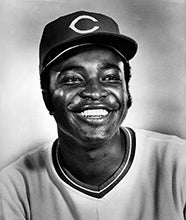

Reds manager Sparky Anderson put Fred Norman into the team's rotation following a trade that brought Norman to Cincinnati from San Diego. Norman was a mainstay on the Reds' staff during back-to-back World Series-winning seasons of 1975 and 1976. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Having entered the National League only two years earlier, the Padres badly needed pitching. They made Norman a part of their rotation and gave him the chance to work regularly with Roger Craig, his former coach in the Dodgers’ system. Now the Padres’ pitching coach, Craig urged Norman to use both his slider and his screwball. Norman went only 3-12 for the Padres, but that record was a product of terrible run support. Norman’s ERA of 3.32 better reflected his pitching. Norman was now on his way.

In 1972, Norman’s bad luck on the mound continued, as he lost seven of his first eight decisions. Opposing scouts were not fooled by Norman’s won/loss record. Several National League general managers contacted the Padres about Norman’s availability, including the Houston Astros and San Francisco Giants.

But it was another team that won the bidding war. On June 12, the Cincinnati Reds offered a package headlined by minor league outfield prospect Gene Locklear. The Padres took the offer, making Norman a Red. Initially, the trade brought a shock to Norman’s system, if only because of the Reds’ strict policy regarding long hair, beards, and mustaches. “Back then I had a mustache and long hair, and of course, there was none of that on the Reds,” Norman told writer Scott Lauber. “I get a call from manager Sparky Anderson, and he says, ‘You know those locks you got? That’s got to go. And you know that thing above your lip? That’s got to go, too.’”

Norman cut his hair and shaved the mustache, but that was a small price to pay for being on the Reds. Norman now had one of the game’s best offensive attacks primed to score runs for him. The Reds’ lineup featured a cavalcade of stars: Johnny Bench, Tony Pérez, Joe Morgan, George Foster and Pete Rose. The Reds also played well in the field, with a defensive core led by Bench, Morgan, shortstop Davey Concepcion and center fielder Cesar Geronimo, giving Norman a level of support he had never seen previously.

In making the trade, the Reds viewed Norman as a potentially important part of their rotation. They liked his competitiveness, regarding him as a bulldog who battled hard, particularly on days when he lacked stuff or control. The Reds also liked Norman’s ability to command and mix his pitches, making him unpredictable to hitters.

After joining the Reds in mid-1973, Norman went 12-6 and put up an ERA of 3.30. With the addition of the 30-year-old Norman, the Reds now had a highly capable No. 4 starter behind the trio of Jack Billingham, Ross Grimsley and Don Gullett.

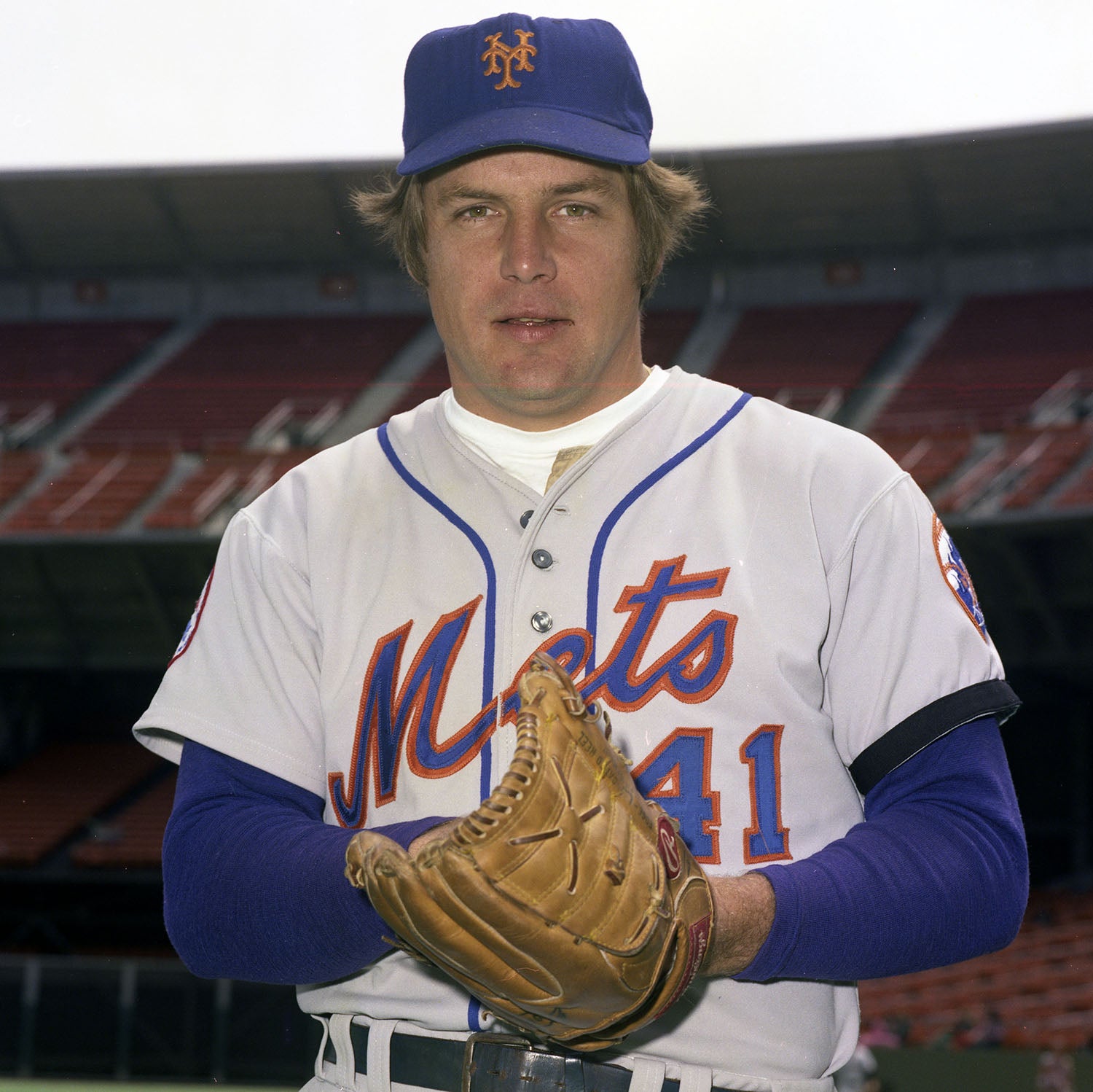

While the Reds’ offense garnered most of the headlines in 1973, Norman played an important role, too. With a deeper pitching staff aided by Norman, the Reds won 99 games and captured the National League West, earning an NLCS date with the New York Mets. In the playoffs, Norman made one effective start against the Mets, allowing just a run in five innings, but the Reds dropped the series in five games.

In 1975 and ’76, Norman continued to contribute in a complementary way to the Reds’ dominance. He now had a full repertoire of five pitches (fastball, screwball, slider, curve and change-up), and a willingness to throw any pitch on any count. Over that two-year span, he won 24 games against only 11 losses, pitching both as a starter and occasional reliever. In August of 1976, Sparky Anderson told the Sporting News: “Right now Fred is the best pitcher in the league.”

In contrast to his regular season success, Norman struggled in the 1975 and ‘76 World Series, putting up an ERA of 6.10 in 10 innings, but his postseason hiccups did not hurt the Reds. Instead, Norman and his teammates picked up a pair of World Series rings.

As a member of the Reds, Norman was often subjected to quick removal by Anderson, the manager known as “Captain Hook.” At times, Norman complained privately to Anderson, but the manager allowed it because of his respect for a serious, hardworking pitcher like Norman. All along, Norman remained a consistent mainstay in the Reds’ rotation, winning in double figures every season for Anderson.

Even as the Reds’ run of dominance came to an end in the late 1970s, Norman continued to contribute. In 1978, he raced out to a 10-3 start. The Reds believed that Norman’s first-half performance earned him a place on the National League All-Star team, but the veteran left-hander did not make the cut. Some observers believed that Norman’s exclusion was caused by the presence of four other Reds on the All-Star Game roster. Norman did not pitch as well over the second half of 1978, but he remained the Reds’ No. 2 starter behind Hall of Fame Tom Seaver.

Norman would continue to pitch effectively again in 1979, winning 11 games and logging 177 innings, but the team allowed him to pursue free agency that winter. At the time, the Reds took a passive approach toward free agents, allowing Norman to sign with the Montreal Expos, where manager Dick Williams made him part of a revamped bullpen. For the first time since his Padres days, Norman saw his ERA rise above 4.00. Even though he did not pitch terribly, and appeared to have enough left to come back for another season, the Expos released Norman the following spring, ending his career.

With his playing days behind him, Norman worked for a few seasons as a minor league coach in the Reds’ organization and then left the game entirely. He decided to open a new business, a garbage removal service in the Los Angeles area. Norman now lives in retirement in North Carolina.

For much of his career, Norman was an overlooked player, one who received little acknowledgment for his contributions to the Big Red Machine of the 1970s. Perhaps that has started to change; in 2018, the Reds named Norman to their Hall of Fame.

No matter the level of recognition, Norman still has those two World Series rings from his days in Cincinnati. That’s quite the accomplishment for the pitcher who spent all of those seasons swinging between the minors and the big leagues, and then had to endure pitching in front of all of those empty seats in San Diego. With Norman, as it does so often in baseball, perseverance and patience paid the bills.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame