- Home

- Our Stories

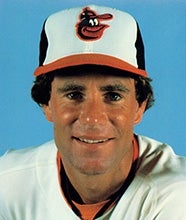

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Grant Jackson

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Grant Jackson

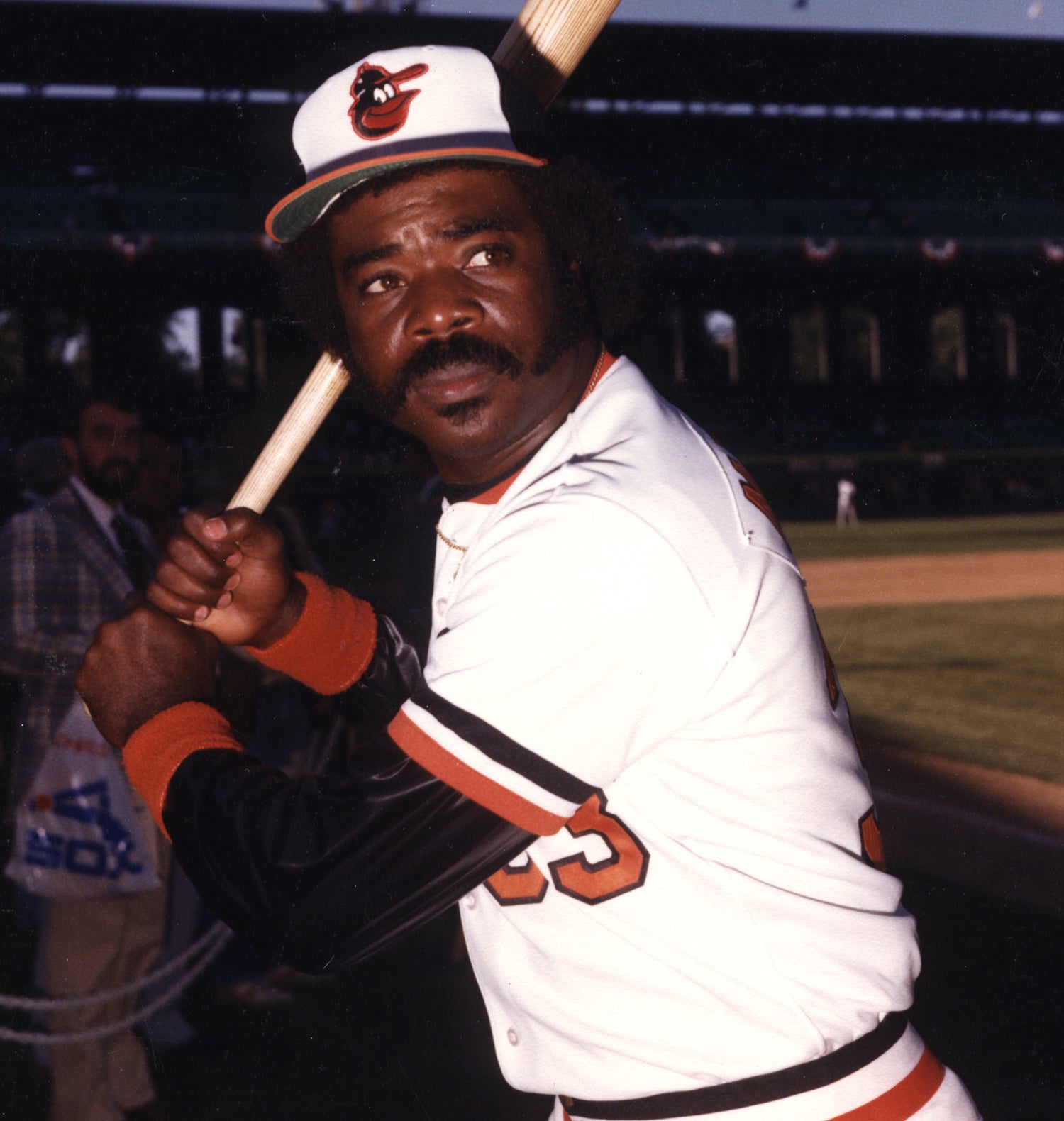

Willie Stargell’s two-run, sixth-inning home run in Game 7 of the 1979 World Series gave the Pirates a lead they would not relinquish and virtually clinched Fall Classic MVP honors for the future Hall of Famer.

But Grant Jackson played as important a role as Stargell that night, extinguishing a Baltimore rally the inning before Stargell’s blast and then shutting down the Orioles for two frames before handing the ball to closer Kent Tekulve.

Jackson got the win, carving out a place in Pittsburgh sports history. It was the peak of an 18-year big league career that saw Jackson transition from a starter into one of the game’s most effective left-handed relievers.

Born Grant Dwight Jackson on Sept. 28, 1942, in the northwest Ohio town of Fostoria, he was the fourth of nine children of Joseph and Luella Jackson. His father passed away soon after Jackson graduated high school, leaving one of his older siblings, Carlos, to take on the role of mentor.

A star basketball player at Fostoria High School who also lettered in track and football, Grant played American Legion baseball during the summer. He had only a mild interest in the game before attending a Milwaukee Braves tryout camp at age 16.

“One of the men saw me playing in the outfield,” Jackson told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1969, “and he asked me why I didn’t try pitching because I had a strong arm. It really didn’t make much difference to me because I wasn’t that interested in becoming a baseball player. I wanted to be a football player. I was a big fan of (Cleveland Browns running back) Jimmy Brown and watching him put a lot of ideas into my head. I wanted to do what he was doing.”

Jackson received several scholarship offers to play football and eventually enrolled at nearby Bowling Green State University. Carlos had starred as a football player at Bowling Green – finishing second in the Mid-American Conference in rushing in 1955 – and later served as a coach for several seasons before passing away in 1974.

But Grant never played college football, instead signing a contract with the Phillies.

“We needed money,” Jackson told the Inquirer. “I had eight brothers and sisters. I had been pitching and knew I had a chance to sign. There was a Phillies scout in our town named Tony Lucadello and he came around and offered me a bonus of $1,500 to sign. I took it.”

Lucadello signed dozens of prospects for the Phillies over the years, including Fergie Jenkins and Mike Schmidt. But soon after Jackson signed, he received a better offer from the Braves.

“Once in a Legion game in Lima, I had pitched both games of a doubleheader and struck out 33,” Jackson told the Inquirer. “(A Braves scout) saw the games. He told me he was prepared to offer me $35,000. I had to tell him I signed two days earlier with the Phillies.”

Jackson began his pro career in 1962 with Class C Bakersfield of the California League and went 4-5 over 29 games. He returned to Bakersfield in 1963, and this time went 12-8 while striking out 159 batters over 176 innings – employing a sinking fastball that would eventually become his bread-and-butter pitch. A year later, Jackson fanned 179 batters over 148 innings at the Class A and Double-A levels. Then in 1965, Jackson pitched most of the season for Triple-A Arkansas of the Pacific Coast League after impressing the Phillies’ brass during big league Spring Training camp.

“He comes to camp with a better arm than his credentials,” Phillies manager Gene Mauch told the Philadelphia Daily News.

The confident Jackson – who earned the nickname “Buck” – believed that he would soon be pitching in the big leagues. He struck out 158 over 155 innings in Triple-A while going 9-11 with a 3.95 ERA before the Phillies called him up to the big leagues when rosters expanded at the end of the year. Jackson debuted on Sept. 3 against the Reds, allowing three runs over two innings of relief while being tagged with a loss. He pitched in six games down the stretch, including two starts, going 1-1 while striking out 15 batters in 13.2 innings.

Jackson competed for the No. 4 starter role in the spring of 1966 and made the Opening Day roster. He pitched twice out of the bullpen but was sent back to Triple-A in late April after the Phillies acquired veteran starters Bob Buhl and Larry Jackson in a deal that sent Jenkins to the Cubs. He spent the rest of the year with San Diego of the Pacific Coast League, going 10-8 with a 3.96 ERA.

Jackson pitched for Caguas of the Puerto Rican Winter League for the second straight year following the 1966 campaign and made the Phillies as a reliever in 1967. In 43 games – including four spot starts – Jackson was 2-3 with a 3.84 ERA while fanning 83 batters over 84.1 innings.

He reprised his relief role in 1968, going 1-6 with a 2.95 ERA in 33 games for a Phillies team that finished 76-86. Mauch was relieved of his managerial duties midway through the season, and new manager Bob Skinner put Jackson in the rotation in 1969.

“I’m not a reliever,” Jackson told the Daily News in Spring Training of 1969. “I can’t adjust to throwing down there every day. My left index finger is much shorter than my middle finger and I get blisters from the uneven pressure I have to put on the ball.

“People ask me if this is a now-or-never year. I tell them it’s only going to be a ‘now’ year. I’ve had my last ‘never’ year. This is going to be my year. All I need is a little daylight.”

Jackson proved to be right. He started the Phillies’ fifth game of the season, allowing just one run over nine innings in an 8-1 win over Pittsburgh. He was 9-10 at the All-Star break but with a tidy 3.32 ERA – a performance that earned him a spot on the National League All-Star Game roster. He finished the year with a 14-18 record, 180 strikeouts and a 3.34 ERA over 253 innings for the 99-loss Phillies.

But in 1970, Jackson did not get along with new manager Frank Lucchesi and words were exchanged between them after Lucchesi pinch-hit for Jackson in the middle of an at-bat on July 1 in Montreal with the Phillies trailing the Expos 2-0. The Phillies eventually lost 4-1 and Jackson was charged with the defeat, dropping his record to 1-6.

“He threw a bat, kicked a batting helmet and said some things,” Lucchesi told the Daily News. “I went in (to the clubhouse during the game) and…Buck gave me some lip, which I didn’t appreciate. I said: ‘That’ll cost you $50. And if you say anything else, it’ll cost you $100.’”

The relationship deteriorated from that point, with Jackson and Lucchesi butting heads for much of the rest of the season. Jackson finished the year 5-15 with a 5.29 ERA over 149.2 innings. On Dec. 16, 1970, the Phillies traded Jackson, Jim Hutto and Sam Parrilla to the Orioles in exchange for outfielder Roger Freed. At that point, Jackson had a career record of 23-43.

Over the next 12 seasons, Jackson would go 63-32 and pitch for six teams that advanced to postseason play.

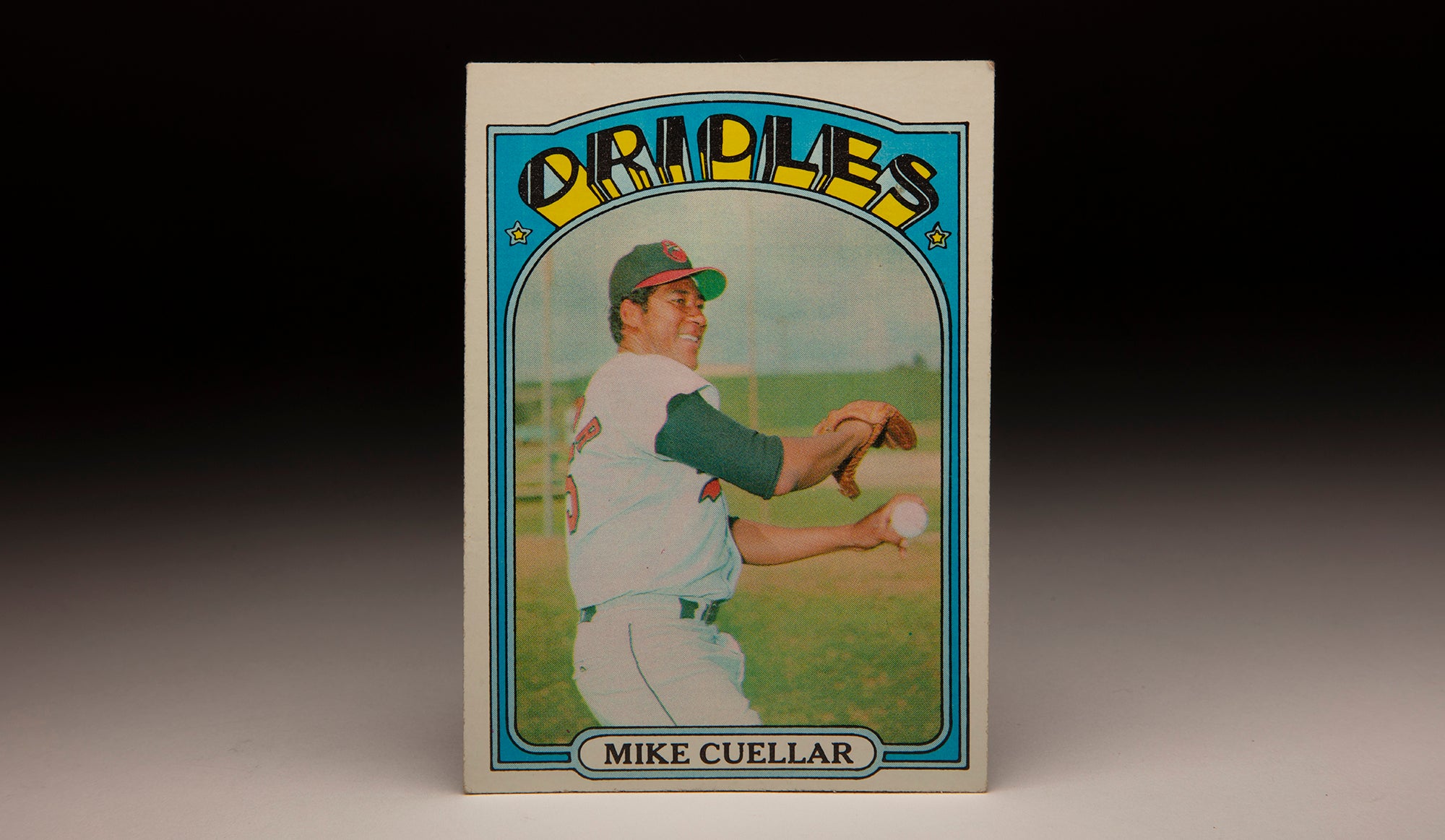

In 1971, Jackson was the de facto fifth starter for a Baltimore team that featured four 20-game winners: Mike Cuellar, Pat Dobson, Dave McNally and Jim Palmer. Jackson’s nine starts were the fifth-most on the team as he went 4-3 with a 3.13 ERA over 77.2 innings. He did not pitch in the Orioles’ sweep of the Athletics in the ALCS but made his postseason debut in Game 4 of the World Series against the Pirates, working two-thirds of an inning in relief of Dobson. In a game at Three Rivers Stadium that portended his future, Jackson got Stargell to ground out to second base to end his outing when Orioles manager Earl Weaver pinch-hit for Jackson in the top of the seventh.

Jackson did not pitch again in the World Series, which Pittsburgh won in seven games.

Jackson did not make any starts in 1972, appearing in 32 games out of the bullpen as Weaver once again leaned heavily on his four main starters. Jackson went 1-1 with a team-high eight saves and 2.63 ERA as Baltimore finished out of first place for the first time in the four-year history of the American League East.

Then in 1973, the Orioles returned to the top of the division as Jackson went 8-0 with nine saves and a 1.90 ERA in 45 games as Baltimore’s primary stopper out of the bullpen. He appeared in two games in the ALCS vs. Oakland, allowing no runs over three innings and picking up the win in Game 4 with 2.2 innings of hitless relief. But the A’s won the series in five games.

“Earl says: ‘If you’re afraid to throw strikes, we’ll get somebody in here for you,” Jackson told the AP about his successful conversion to a reliever. “He doesn’t like to walk anybody. One reason why Baltimore always has one of the best pitching staffs is because they have one of the best defenses, so why walk anybody? If you keep it inside the park, they’ll chase it down.”

Jackson picked up the save for the Orioles on Opening Day in 1974 but was tagged with his first loss in more than a year two days later against the Tigers. He was 2-4 with 12 saves and a 2.72 ERA heading into play on Sept. 27 when he reeled off four wins over five days to help the Orioles fend off the Yankees and win the AL East for the fifth time in six seasons. Jackson picked up the victory on Oct. 1 against the Tigers as Baltimore clinched the division.

But once again, the Orioles fell to the A’s in the ALCS as Jackson appeared in just one game, allowing two unearned runs over one-third of an inning in Baltimore’s 5-0 loss in Game 2. The runs came on a three-run homer by Ray Fosse, who came to the plate after Frank Baker – who was playing shortstop after slick-fielding Mark Belanger was removed for a pinch-hitter – was charged with an error on a two-out ball hit by Claudell Washington.

In 1975, Jackson was 4-3 with seven saves and a 3.35 ERA in 41 games. Weaver again worked his starters as much as possible, but change was in the air – both on and off the field – after the Orioles finished four-and-a-half games behind the Red Sox in second place in the AL East.

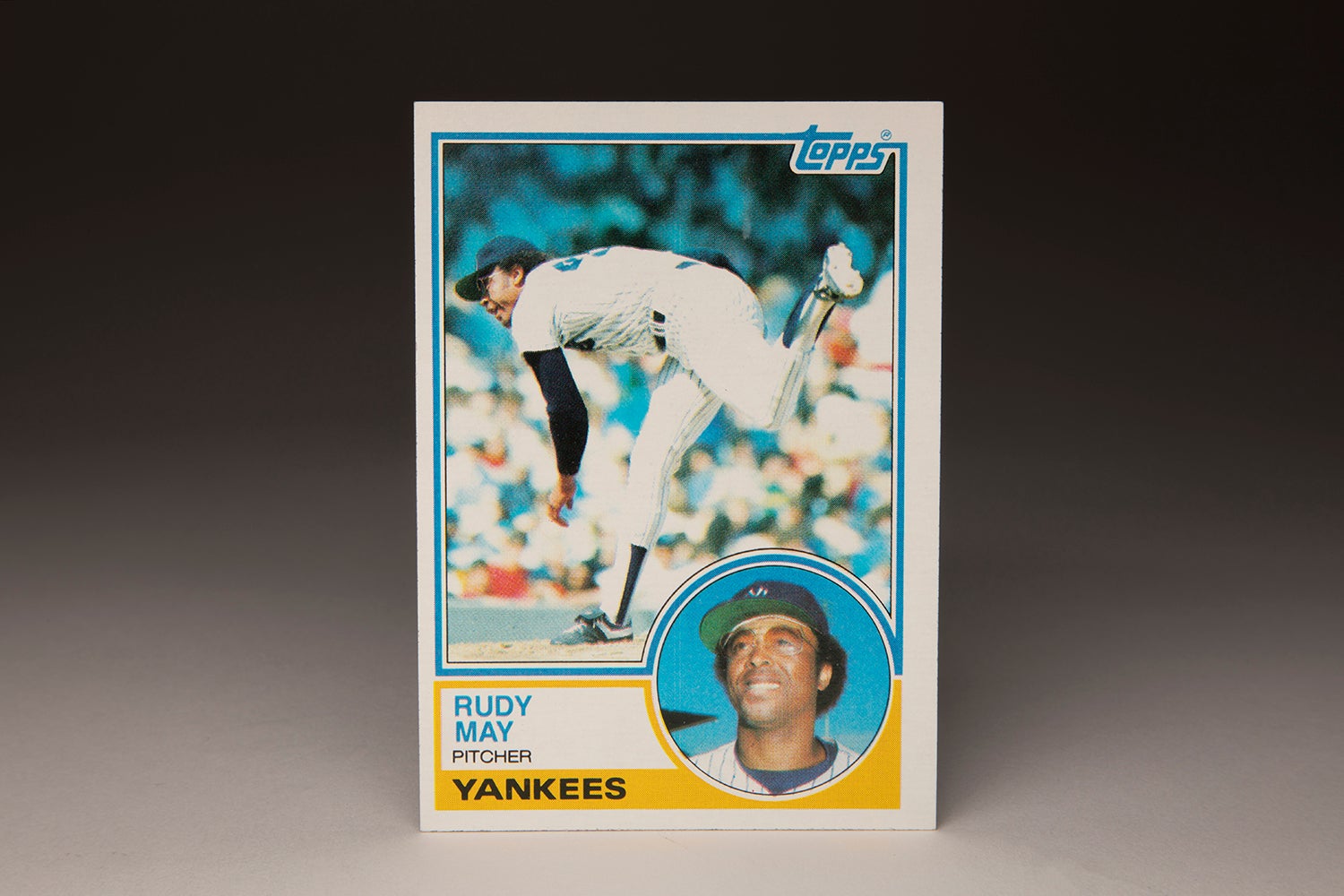

The 1976 season began with a work stoppage following the arbitrator’s decision that made Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally free agents following the 1975 campaign. Once play began, Jackson pitched well until three rough outings in early June as trade rumors swirled. On June 15, the Orioles and Yankees executed a rare deal between contenders when Baltimore sent Doyle Alexander, Jimmy Freeman, Elrod Hendricks, Ken Holtzman and Jackson to New York in exchange for Rick Dempsey, Tippy Martinez, Rudy May, Scott McGregor and Dave Pagan. The trade was meant to bolster New York’s pennant push while the Orioles stocked up on prospects.

Jackson wasted no time getting acclimated to New York, picking up a win in his first appearance on June 18 and giving manager Billy Martin an effective veteran out of the bullpen. Jackson even made two spot starts down the stretch, throwing a five-hit shutout against Detroit in his last appearance of the year on Sept. 24. He finished the season with a combined 7-1 record, four saves and a 2.54 ERA as the Yankees won the AL East for the first time in team history.

Pitching in the postseason for the fourth time in six seasons, Jackson made two appearances against the Royals in the ALCS. He allowed one run over 2.1 innings in Game 4 as the Royals won 7-4 to push the series to a deciding fifth game.

In Game 5, Jackson entered the game in relief of starter Ed Figueroa with one on and no one out in the top of the eighth. Jackson quickly allowed a single to Jim Wohlford before surrendering a three-run home run to George Brett that tied the ballgame at 6. Dick Tidrow relieved Jackson to start the ninth and kept Kansas City off the board, setting up Chris Chambliss’ walk-off home run against Mark Littell that sent New York to the World Series.

After the game, some media members questioned why Martin turned to Jackson to face Brett instead of Sparky Lyle, who led the AL with 23 saves that year. But in the celebration that followed Chambliss’ home run, that strategic moment was largely forgotten.

The Yankees were swept by the Reds in the World Series, and Jackson appeared in just one game – working 3.2 innings and allowing two runs in Game 3. Following the season, MLB held an expansion draft to stock the Seattle Mariners and Toronto Blue Jays – and the Yankees left Jackson unprotected, just like the Phillies did following the 1968 season when the Expos, Pilots, Royals and Padres stocked up for their inaugural seasons.

But this time, Jackson was drafted by the Mariners with the 11th pick in the draft on Nov. 5, 1976. A month later, the Mariners traded Jackson to the Pirates in exchange for Craig Reynolds and Jimmy Sexton. That same day, the Pirates traded Manny Sanguillén and cash to the Athletics for manager Chuck Tanner, who had been an early adapter of the new bullpen tactics with the White Sox in the mid-1970s.

Soon, Tanner and the Pirates had a bullpen that featured future Hall of Famer Goose Gossage, Terry Forster, Kent Tekulve and Jackson.

“Eight or nine clubs talked to us about Jackson,” Mariners manager Darrell Johnson told United Press International after the trade with the Pirates. “The man is a heckuva relief pitcher. He could make the difference in a pennant race and obviously the Pirates felt that way, too.

“If the Pirates win their division by three or four games next season, Grant Jackson will be the difference. (But) we’re after young people. We know we have to build for the future.”

The Pirates, meanwhile, were aiming for the present.

“We could even spot start (Jackson),” Tanner told UPI, “but right now our plans are to use him strictly in the bullpen. He’s proved he can do the job.”

Jackson did his job in 1977, going 5-3 with four saves and a 3.86 ERA over 91 innings in 49 games. Gossage saved 26 games and struck out 151 batters over 133 innings, while Tekulve went 10-1 with seven saves in 72 games. Forster was relegated to middle relief and spot start duties, going 6-4 with one save. But with all that bullpen firepower, the Pirates still fell short of first place – winning 96 games but finishing five games behind the Phillies.

Gossage and Forster left via free agency following the season, however. Suddenly, Tekulve was the closer and Jackson was his set-up man. It proved to be a championship combination.

In 1978, Tekulve appeared in 91 games, saving 31 while going 8-7. Jackson ranked second on the team in appearances with 60 while going 7-5 with five saves and a 3.26 ERA. But Pittsburgh once again finished second to Philadelphia in the NL East.

Doubling down on their bullpen strategy, the Pirates acquired reliever Enrique Romo from the Mariners on Dec. 5, 1978 – along with Rick Jones and Tom McMillan – in exchange for Odell Jones, Mario Mendoza and Rafael Vásquez. Romo would team up with Jackson and Tekulve as one of the first seventh-eighth-ninth trios the game had seen, often allowing Tanner to remove his starters after six innings.

“If we take this season one game at a time, we’re going to be tough to beat,” Jackson told the Pittsburgh Press during the 1979 season. “We have the depth now where one guy can take his rest and the other guy will do just as good a job.”

Jackson predicted during Spring Training that the Pirates would clinch the National League East title on Sept. 25. He proved to be off by less than one week as Pittsburgh wrapped things up on Sept. 30 with a win over the Cubs and an Expos loss to Philadelphia. Jackson ended the season with an 8-5 record, 14 saves and a 2.96 ERA in a career-high 72 appearances.

In the postseason, Jackson was nearly perfect. He appeared in two games of the NLCS vs. the Reds, winning Game 1 with 1.2 innings of scoreless relief and then recording the first out of the eighth inning of Game 2 (with the Pirates ahead 2-1) as Tanner employed a bullpen by committee. The Reds eventually tied the game in the ninth off Tekulve but Pittsburgh rallied in the 10th and Don Robinson closed the door for the victory.

The Pirates swept the series but entered the Fall Classic against the Orioles as underdogs.

“We aren’t going down there to lose,” Jackson told the AP before Game 1 in Baltimore. “They’ve got good pitching. We’ve got good pitching. It should be a good series.”

“I’ll take our bullpen over Baltimore’s.”

Both Tekulve and Romo – who made 84 appearances during the regular season and won 10 games as Tanner deployed his bullpen regularly – had shaky moments in the NLCS vs. the Reds. But Jackson wasn’t concerned.

“Everybody’s talking about how Enrique didn’t do this and that in the playoffs,” Jackson told the AP. “But it was his first time in that situation, and he was probably a little scared. But I talked to him in Spanish (Jackson made his offseason home for years in Puerto Rico) and he’ll be all right.”

In fact, Romo gave up five hits and three walks over 4.2 innings in the World Series while appearing in only two games (both Pirates losses). Jackson, meanwhile, was remarkably effective for a pitcher who had turned 37 just days before the end of the regular season.

Jackson worked a scoreless inning in Game 1 in Pittsburgh’s 5-4 loss then retired the only batter he faced in an 8-4 Baltimore win in Game 3. He faced the same batter he did in Game 3 – Al Bumbry – the next day in Game 4, and this time Jackson got Bumbry to ground into a double play. Once again, Jackson was replaced by the next inning, limiting his outing to one batter.

In Game 7, however, Jackson had to be much more durable. The Pirates trailed 1-0 after four innings, and Tanner pinch-hit for starter Jim Bibby in the top of the fifth. Robinson entered the game in the bottom of the inning and allowed a single and a walk sandwiched around two fly balls, bringing up the lefty-hitting Bumbry and once again causing Tanner to call on Jackson – who got Bumbry to pop out to third to end the threat.

Stargell’s home run gave Pittsburgh a 2-1 lead in the top of the sixth, and Jackson retired all six batters he faced in the sixth and seventh. But in the eighth, Lee May drew a one-out walk. Bumbry followed May to the plate and finally found some success, drawing another walk. Baltimore manager Earl Weaver then sent Benny Ayala up to pinch-hit for Kiko Garcia, who finished the World Series with eight hits (in 20 at-bats for a .400 average) and six RBI. Tanner countered with Tekulve, and Weaver then countered by pinch-hitting Terry Crowley for Ayala.

Crowley grounded out to leave runners on second and third with two outs, and Tekulve intentionally walked Ken Singleton to get to Eddie Murray. On a 2-and-2 pitch, Murray hit a ball to deep right field that died on the warning track and fell into Dave Parker’s glove for the third out.

“I walked Lee May on purpose because he could tie the game with one swing of his bat,” Jackson told United Press International after Game 7. “I walked Bumbry because the umpire (Jerry Neudecker of the American League) was squeezing the strike zone. I threw some strikes – at least they were National League strikes.”

With the threat ended, the Pirates pushed two runs across the plate in the ninth against five different Baltimore pitchers, and Tekulve set down the side in order in the bottom of the ninth to preserve Jackson’s victory and Pittsburgh’s 4-1 win. He became the sixth Black pitcher to win an AL/NL World Series game.

For Jackson and his family, the 1979 season was the apex of their big league life.

“I still haven’t come down from winning the World Series,” Jackson’s wife Millie, who married Jackson while he was still with the Phillies, told the Bradenton (Fla.) Herald in the spring of 1980. “I can’t explain it. It’s not the money; it’s the pride.”

Jackson virtually duplicated his 1979 season in 1980, going 8-4 with nine saves and a 2.92 ERA over 61 games. But the Pirates finished third in the NL East.

Then in 1981, Jackson was 1-2 with four saves and a 2.51 ERA through 35 games when the Pirates sold his contract to the Montreal Expos on Sept. 1. Jackson was on the verge of gaining his 10-and-5 rights – which would have allowed him to veto any trade – so the deal was not unexpected. But he struggled with Montreal as the Expos finished first in the NL East in the second half of that season, going 1-0 with a 7.59 ERA over 10 games. His win came against the Pirates on Sept. 23 when he pitched two scoreless innings of relief.

He did not pitch in the postseason.

On Jan. 14, 1982, the Expos traded Jackson to the Royals in exchange for Ken Phelps. He went 3-1 in 20 games with Kansas City before being released on July 9. Two months later, he signed with the Pirates and made one appearance – allowing a grand slam home run against the Mets’ Ron Hodges before retiring the final two batters he faced on Sept. 8. It would be the last game of his big league career.

The Pirates released Jackson on Oct. 4, 1982, but he quickly returned to the organization as a coach in 1983. He remained on Tanner’s staff through 1985 when Tanner was dismissed before joining the Reds – and former teammate Davey Johnson, who was the team’s manager – as bullpen coach in 1994 and 1995. He continued as a minor league coach for another few years before retiring.

On Feb. 2, 2021, Jackson passed away in Canonsburg, Pa., due to complications from COVID-19.

Over 18 big league seasons, Jackson went 86-75 with 79 saves and a 3.46 ERA. And though he often downplayed his role in the Pirates’ 1979 World Championship team, Jackson etched his named into the record books in a bullpen that changed the way managers used relievers.

“I don’t put much stock in being the winning pitcher of the seventh game,” Jackson told the Pittsburgh Press in the spring of 1980. “It could just as well been Don Robinson or Dave Roberts. Chuck Tanner brought me in earlier than he usually would, and I did the job. I was just happy to be on the winning side for a change.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum