- Home

- Our Stories

- Paper trail: The Garry Herrmann collection

Paper trail: The Garry Herrmann collection

Lee Allen felt like a prospector who just struck the mother lode after the truckload of boxes were unloaded at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in the spring of 1960. Never mind about finding gold in them thar hills. Allen and future generations of baseball researchers would find gold in them thar boxes.

“It is going to take us at least three years to read all this material,” the Hall’s former historian said after the Cooperstown arrival of the voluminous collection of papers saved by August “Garry” Herrmann, the longtime Cincinnati Reds president and de facto commissioner of Major League Baseball prior to it becoming an official position. “This is the most valuable accumulation of baseball lore ever assembled.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

In fact, it would take much longer — decades, rather than years — to scour and organize the thousands of letters, telegrams, contracts, blueprints, ledgers, newspaper clippings, maps and other ephemera kept by the man who brokered the peace treaty between the warring National and American Leagues at the turn of the 20th century and who would become known as one of the fathers of the World Series.

Herrmann’s agglomeration is by far the largest paper collection in the Hall’s archives, featuring 151 boxes and taking up nearly 90 linear feet of space — roughly the distance between bases on a diamond. For the longest time, it remained a dormant resource, sparingly used by Museum staffers and researchers, but that changed after grants enabled thorough curations of the materials in the mid-2000s and again in 2014.

“The collection is monstrous and covers such a wide swath of baseball history — from 1887 to Herrmann’s last year as Reds president nearly a half century later,’’ said Cassidy Lent, Library director at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “Although it’s been processed and organized a couple of times and used by numerous researchers through the years, I don’t believe everything from the collection has been unearthed. I’m fairly confident more nuggets will be discovered.”

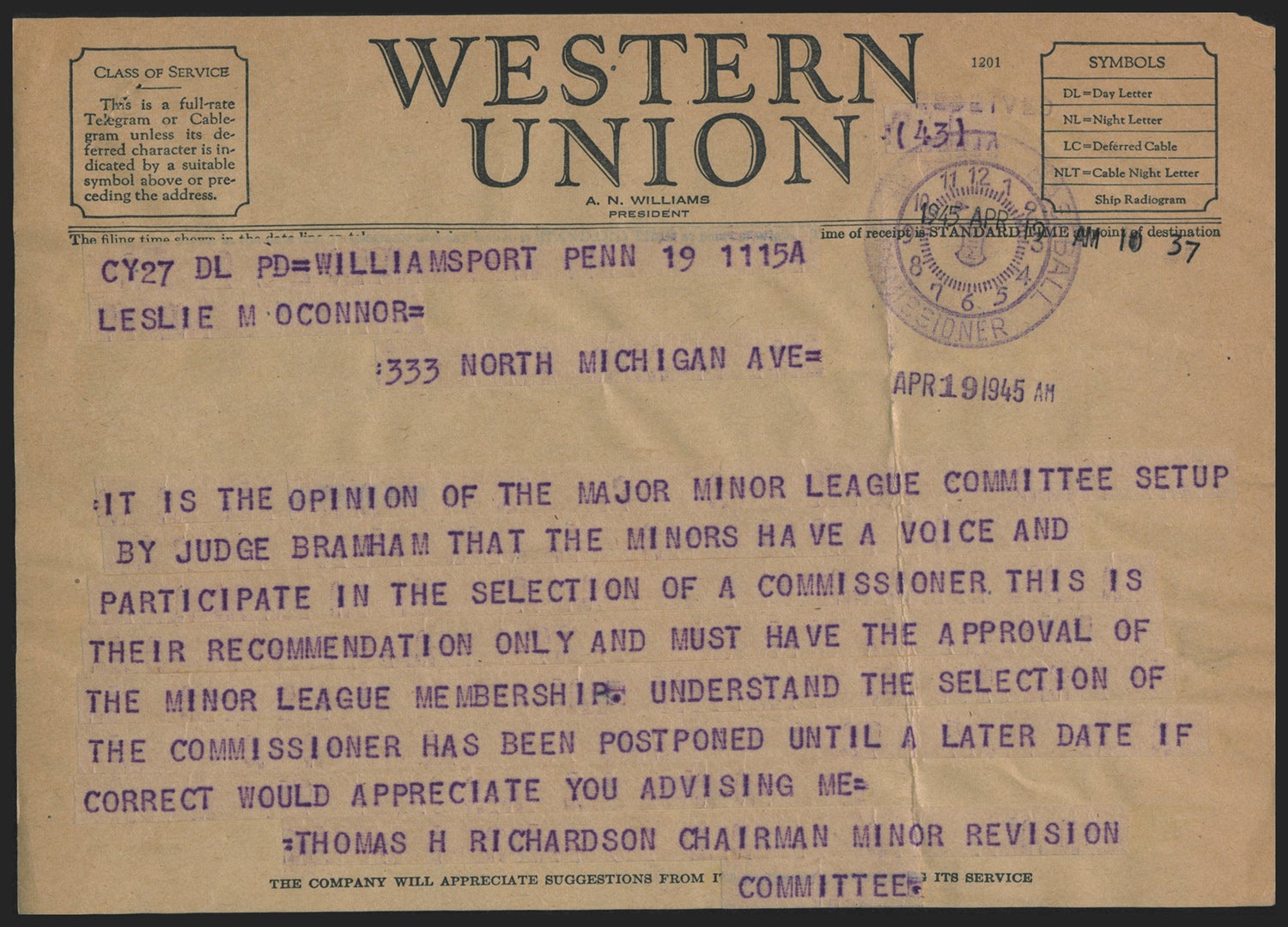

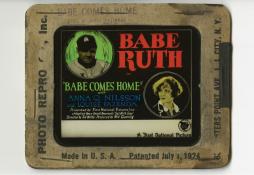

Perhaps nuggets such as one Allen discovered soon after the collection arrived. One of the first boxes he examined contained a telegram about a proposed deal that would have changed the course of baseball history. The Western Union correspondence had been wired to Herrmann by Boston Braves president James Gaffney on July 10, 1914. In it, Gaffney tells Herrmann how he turned down an offer from the Baltimore Orioles to purchase shortstop Claude Derrick and a promising young pitcher by the name of Babe Ruth for $16,000.

“Advised them prohibitive and requested lower price,’’ Gaffney wrote in the telegram. “They replied, asking us to make offer. We made none, as we knew we had no chance.”

The next day, Gaffney’s crosstown rival, the Red Sox, purchased Ruth’s contract. Imagine if the Braves had consummated that transaction? The Sultan of Swat likely never would have wound up in New York and launched the Yankees dynasty, and perhaps the Braves would still be in Boston, instead of making moves to Milwaukee and Atlanta.

Herrmann’s collection has spawned similar, juicy “what-if” discoveries, while providing an insider’s look into the operations of early 20th century ballclubs and the first governing body of baseball.

“It’s a window into a pivotal period of the game’s professional evolution — one that laid the foundation for the structure of today’s game, including the office of commissioner,’’ Lent said. “I think the breadth of what it covers is really what’s significant about the collection. It touches on so many topics, so many issues because Herrmann had a hand and say in seemingly everything.”

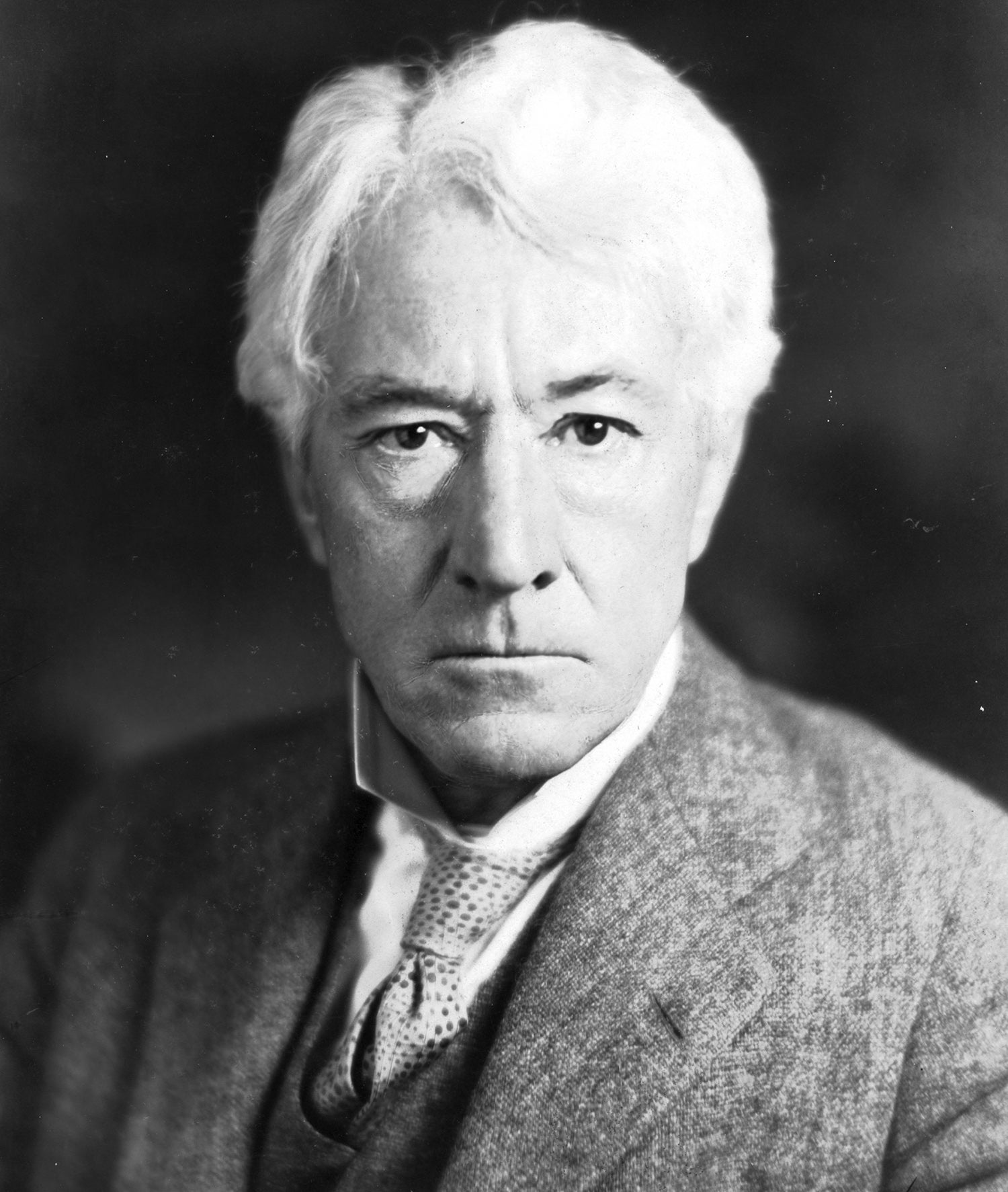

A Cincinnati native and the son of German immigrants, Herrmann became an errand boy and printer’s apprentice after being orphaned at age 11. His work ethic, welcoming personality and precocious organizational skills enabled him to climb the ladder quickly, and by his mid-20s, he had become a prominent businessman and player in the Cincinnati political machine. In 1902, Herrmann and a group of Queen City luminaries purchased the Reds ballclub, and a year later, he helped negotiate the deal between the established National League and upstart American League. As part of the agreement between the two warring factions, a three-person National Commission was formed, featuring the presidents of the two leagues and a neutral person to serve as chair. That person wound up being Herrmann. Despite his stake in the Reds, complaints of bias by him in favor of the Senior Circuit were rarely raised.

Herrmann would earn his World Series reputation after making participation in the Fall Classic mandatory for the two league champions in 1905. This was in response to the previous year when John McGraw refused to allow his NL pennant-winning New York Giants to play the AL champions from Boston. Herrmann would take the lead on other issues during what would be a tumultuous period. One of his toughest challenges was holding MLB together amid labor strife and the poaching of NL and AL players by the upstart Federal League in 1914 and 1915.

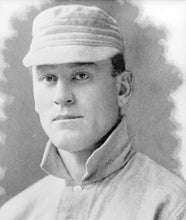

August “Garry” Herrmann helped baseball thrive as the chairman of the National Commission in the early 1900s. His papers from that tenure and from his time as president of the Reds serve as an invaluable look into that era of the National Pastime. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

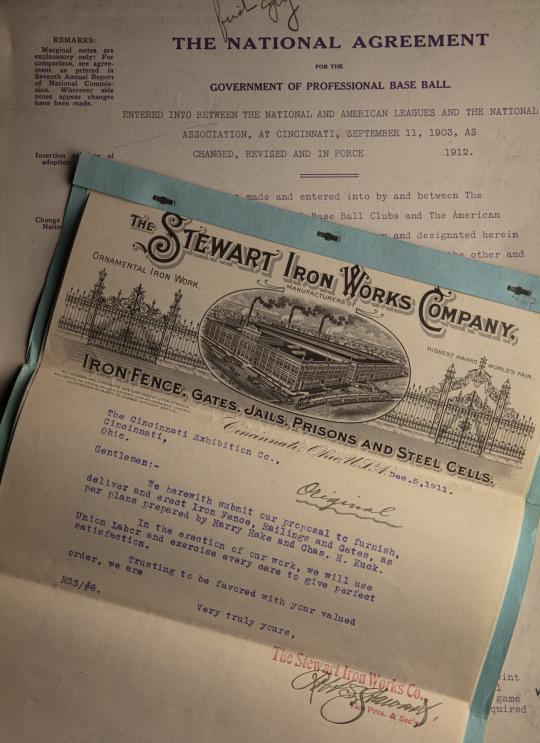

The personal papers of August “Garry” Herrmann comprise more than 150 boxes in the collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. (Collage by Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Herrmann’s most fulfilling baseball moment also would be one that contributed to his departure as chairman and the dissolution of the commission. In 1919, he brought a World Series title to his beloved hometown, but that shining achievement would be tarnished by revelations that the Reds’ opponent, the Chicago White Sox, had thrown the Fall Classic. Herrmann subsequently resigned as National Commission chairman on Jan. 8, 1920, and his position was never filled. The Black Sox scandal forced owners to hire Kenesaw Mountain Landis as the game’s first official commissioner. True to his character of doing what he thought best for the game, Herrmann supported Landis’ appointment.

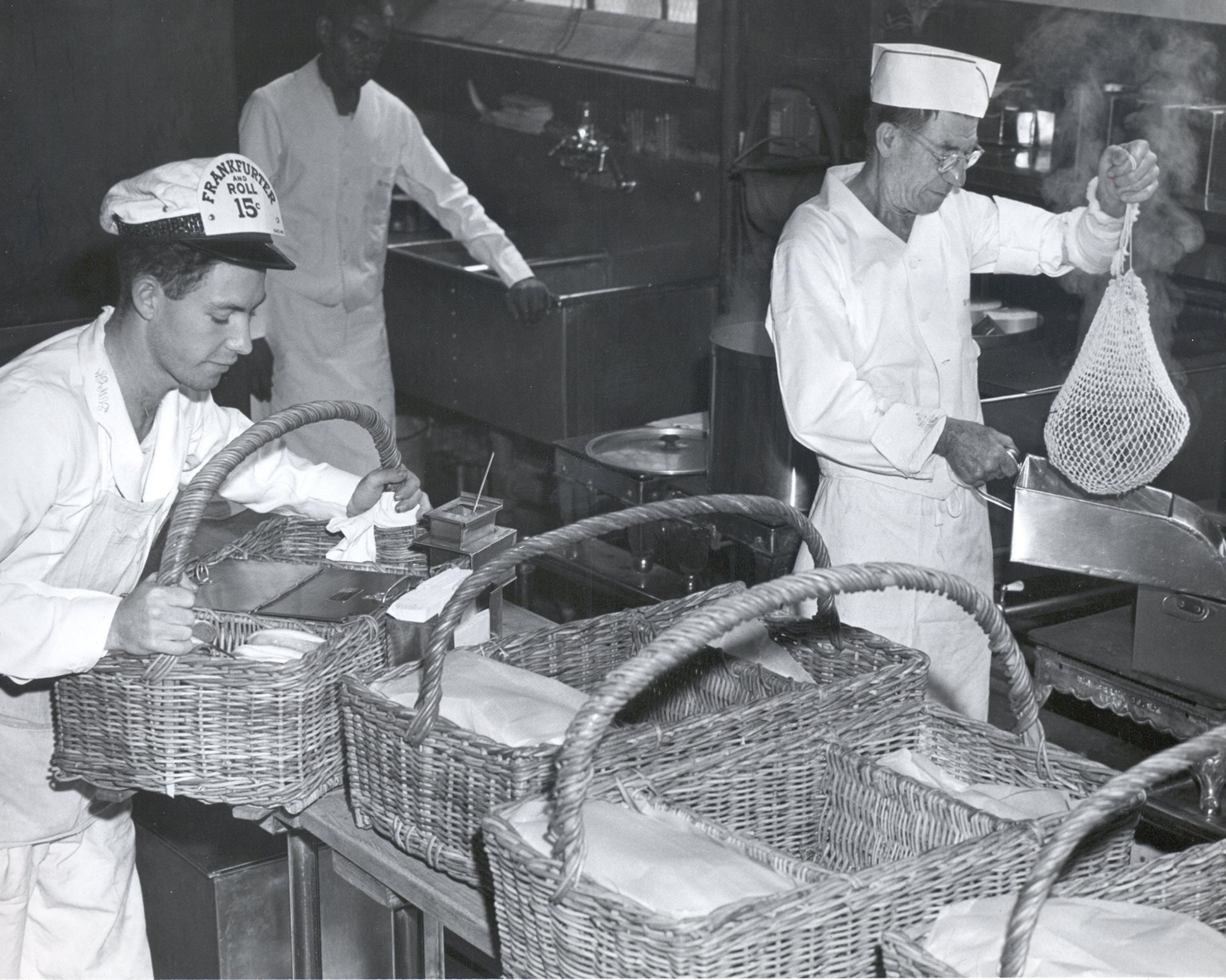

Besides insights into the overarching baseball issues of the early 20th century, Herrmann’s collection has provided researchers with a behind-the-scenes view of what it was like to be an owner in those days. His files include letters from vendors, such as a young soda company called Coca-Cola, as well as prices for bats, balls, uniforms, program advertisements and hotel accommodations for road games. There are even pages devoted to payrolls, like the one from 1906 that listed 21 Reds players earning a combined total of $9,310, topped by future Hall of Famer Joe Kelley’s $2,000 salary.

While running the Reds, Herrmann received frequent inquiries about renting his team’s ballpark. Through letters he kept, we learn that Negro National League president and future Hall of Famer Rube Foster, as well as the owner of a touring championship all-women’s team called the American Bloomer Girls, were among those interested in playing games at Redland Field.

The collection also contains a disturbing, type-written request from the head of the Cincinnati Ku Klux Klan to hold a Klan Day at the park on July 20, 1924. Herrmann responded that the date wasn’t available because the New York Giants were going to be in town. The Reds president added he would discuss the matter upon returning from a trip, but there is no additional correspondence from him in the files, and no record of the KKK rally being held at the ballpark that season, despite another letter of request from the Klan’s leader.

The collection also includes a letter Herrmann received from Warren G. Harding, in which the 29th President of the United States thanked him for his hospitality while attending a Reds home game.

Author John Zinn is one of numerous researchers who’s benefited from the Herrmann collection.

“One of the great things about it is that it gives you not only Hermann’s perspective, but the perspectives of other owners and players because he saved everything,’’ said Zinn, who has written books about the Dead Ball Era and Brooklyn Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets.

“While researching the construction of Ebbets Field, I saw correspondence to Herrmann that the Dodgers owner had run out of money and was asking other owners to bail him out. The newspaper accounts hinted Ebbets was experiencing financial problems, but the correspondence in the Herrmann files gave me the full story, and how Reds co-owner Julius Fleischmann told Herrmann he wasn’t going to lend Ebbets the money. And neither were any of the other owners. As a result, Ebbets had to sell the controlling rights in his club. Without that letter, I never would have known what was truly going on.”

Another author who panned gold combing the Herrmann files is Daniel Levitt, whose book, “The Outlaw League and the Battle That Forged Modern Baseball,” explores in comprehensive detail the Federal League, which briefly threatened the NL and AL’s major league monopoly.

“The back-and-forth correspondence between Herrmann and his fellow owners provided a fascinating look at all the backroom stuff and horse trading going on,’’ Levitt said. “You saw how the owners in the established leagues were trying to buy off [Chicago’s Federal League] owner Charles Weeghman in hopes he would betray his peers and the upstart league would crumble. It was such an adrenaline rush when I discovered that material in Herrmann’s files. As a researcher, it’s what you pray for.”

Following Herrmann’s death at age 71 in 1931, his collection was boxed up and put in storage in a large room beneath a grandstand at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. It remained there for two decades before former Reds owner Powel Crosley Jr. donated it to the Hall, where it now resides in a massive, climate-controlled preservation room.

“Thank goodness it wasn’t thrown away,’’ Lent said. “And thank goodness it ended up with us because there is so much history in that collection.”

With perhaps more nuggets to be mined.

Scott Pitoniak is a nationally honored journalist and author residing in Penfield, N.Y. Among his 35 books is “Remembrances of Swings Past: A Lifetime of Baseball Stories.”