- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

#CardCorner: 1992 Topps Darryl Strawberry

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

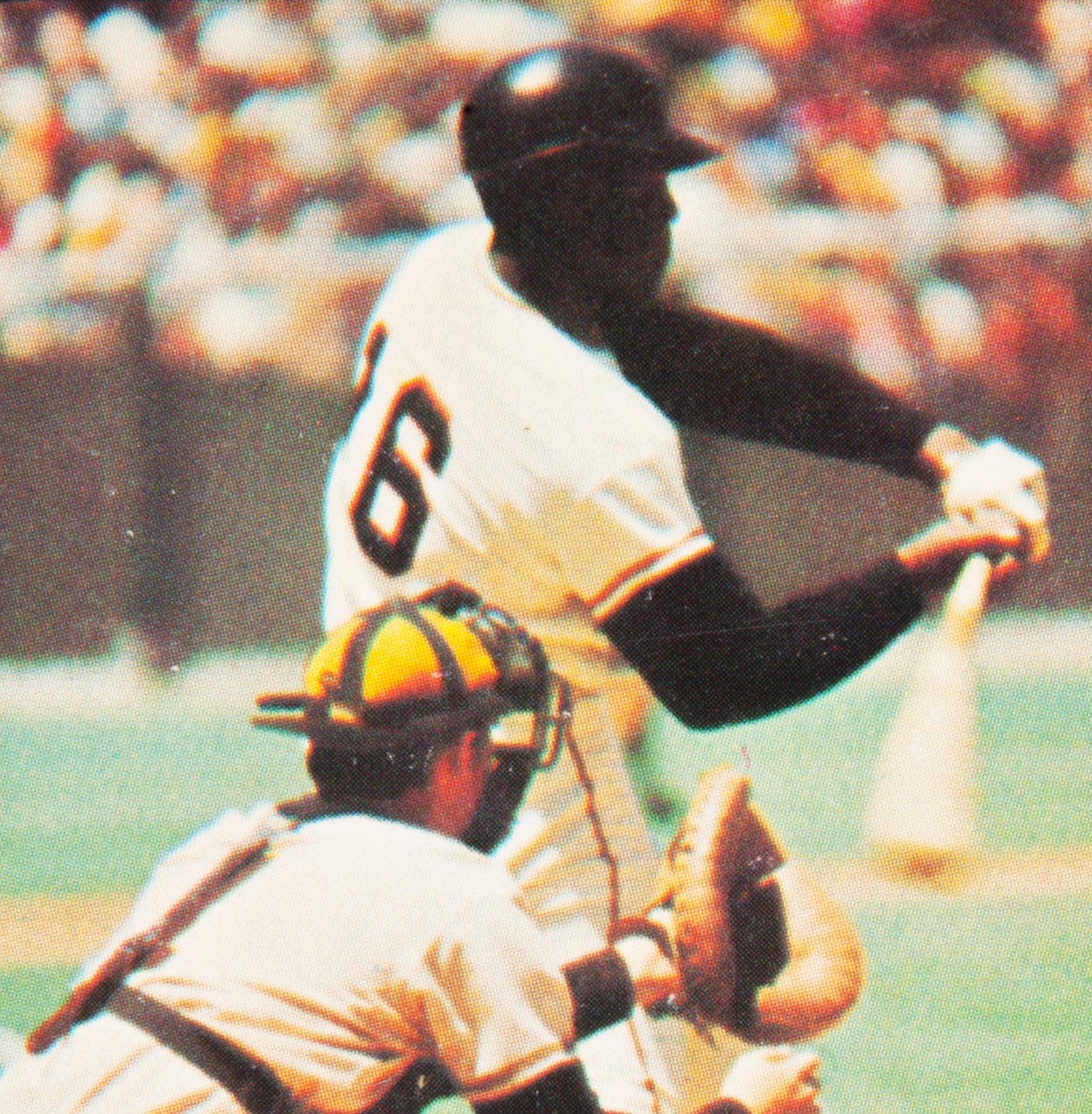

There’s just something about a landscape format on a baseball card. As younger fans, we would typically become excited seeing a card presented in such a way. The game, after all, is best seen in a panoramic view. By creating a horizontal view of the playing field, more players can be included in the photograph, and a wider swath of the field can also be seen. In contrast to the portrait, or vertical style, the landscape view gives you the collector the sense of seeing something different, something special, particularly as it applies to the action on the playing field.

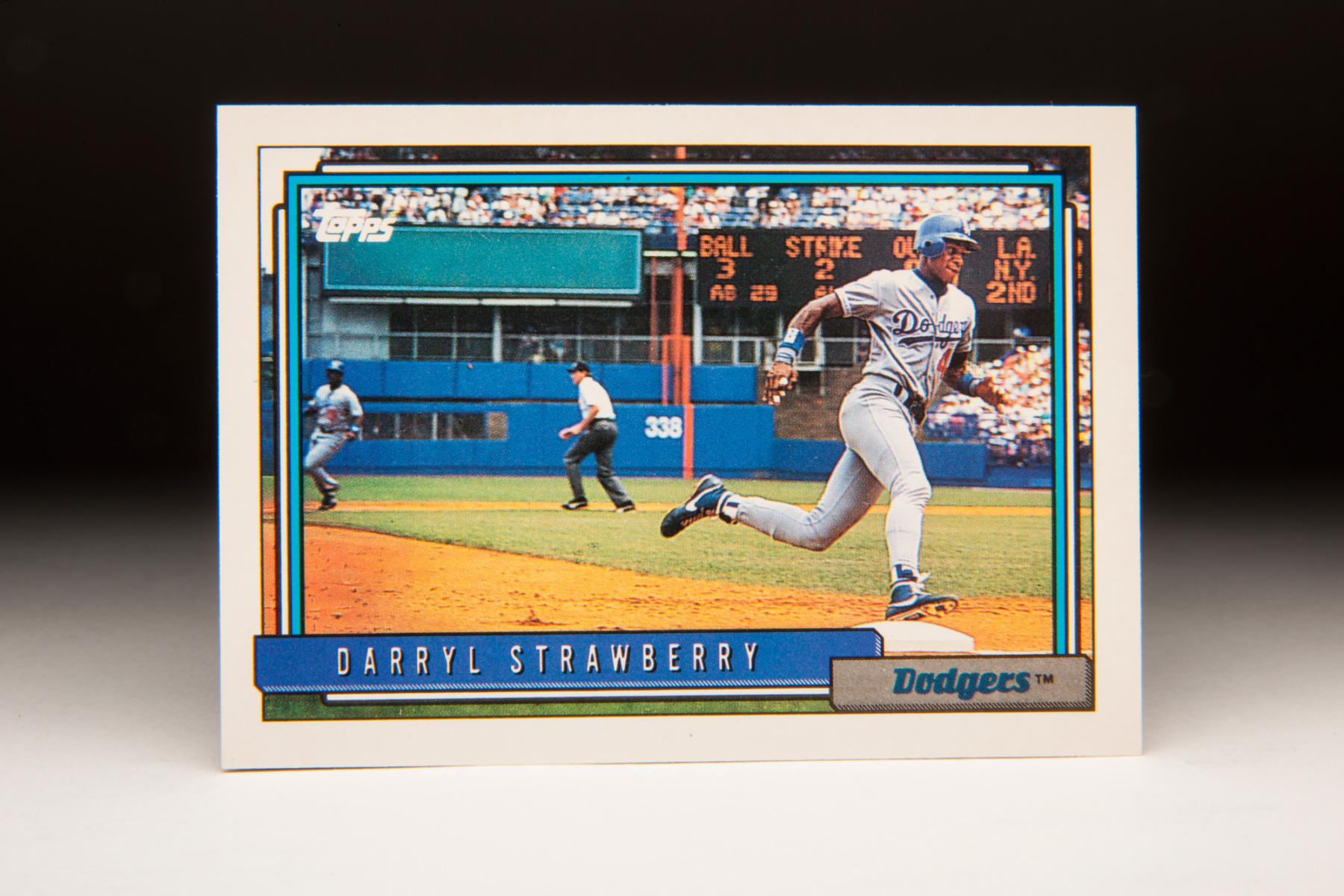

Such feelings came to light when I first took a look at Darryl Strawberry’s 1992 Topps card. We see “The Straw Man,” with his long legs and graceful running style, rounding the third base bag. One of his unknown teammates with the Los Angeles Dodgers is peddling his way into second base, while the umpire is trying to line himself up so as to have a better view of the throw from the outfield.

The Topps photographer secured this photo of Strawberry on a cloudy afternoon at Shea Stadium. Many of Shea Stadium’s classic elements are in play on this card. We see the predominance of the color blue, which was the color of the outfield walls and many of the seats. We also notice the 338-marker down the right field line, an indication of the ballpark’s deep dimensions and the difficulties created for home run hitters. We also notice the Mets’ trademark scoreboard just to the right of the right field foul pole, giving us the count on the batter, the inning by inning run total and the updated score of the game. For fans who attended numerous games at Shea Stadium, this photo captures the essence of the now defunct ballpark.

It’s only fitting that Topps picked Shea Stadium as the backdrop for its first card of Strawberry with the Dodgers. The power hitting outfielder had played for the New York Mets from 1983 to 1990, with Shea Stadium serving as his home park throughout his tenure there. The 1991 season, when this photo was taken, marked the return of Strawberry to Shea as a visiting player. It was a bittersweet moment for a player who had once helped the Mets to a world championship, only to have drug and alcohol problems affect his life and his performance. Strawberry’s departure from the ballclub via free agency upset some Mets fans, who had hoped that he would remain with his first franchise.

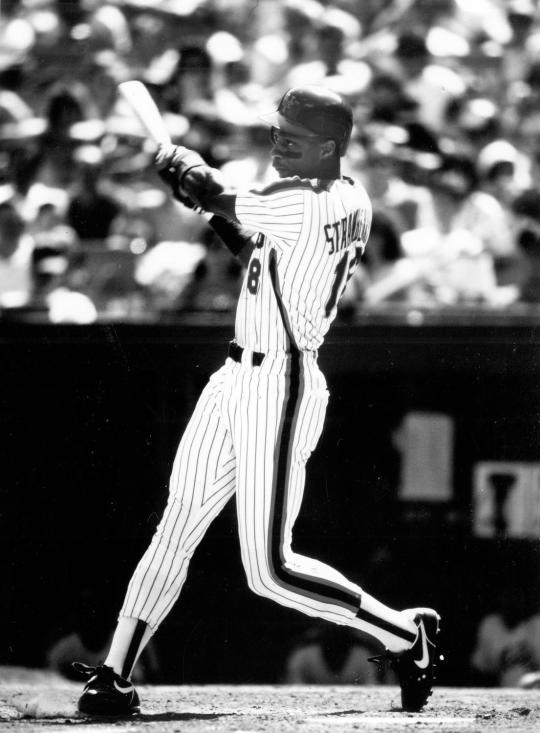

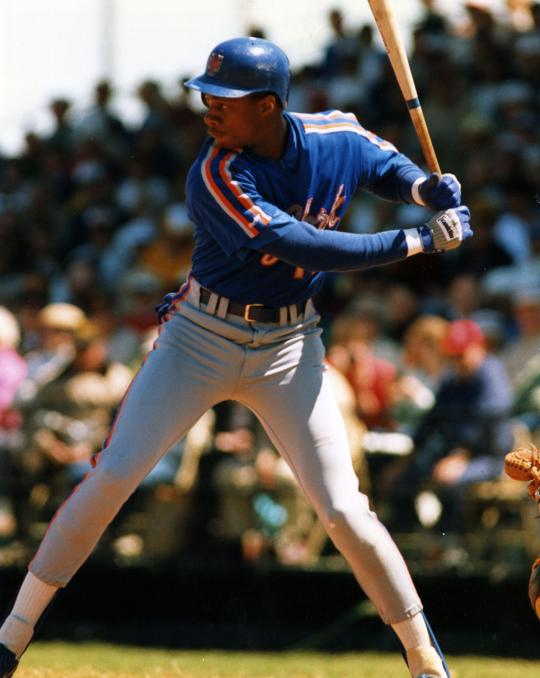

At one time, it would have been hard to imagine Strawberry playing for any team other than the Mets. The franchise made him the No. 1 overall pick in the 1980 draft, selecting him out of Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles. As a high schooler, Strawberry competed against another top-notch prospect in Eric Davis, but most scouts regarded Darryl as the superior talent. With his 6-foot-6 frame and lean build, Strawberry drew physical comparison to Ted Williams. In fact, some writers called him the “black Ted Williams,” likening his smooth swing to that of the “Splendid Splinter.” Such comparisons are never fair; to expect any young player to hit with the kind of precision that Williams did is simply beyond the realm of the reasonable.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

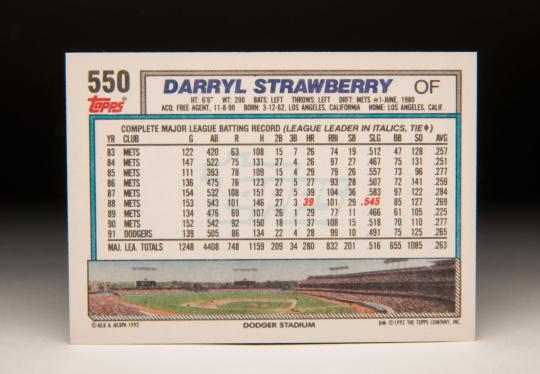

With his talent, his high draft status, and his distinctive last name, Strawberry created an unusual buzz throughout the New York metropolitan area in the early 1980s. Only three years after being drafted out of the high school ranks, Strawberry made his major league debut. Making him their everyday right fielder, the Mets watched Straw as he hit 26 home runs, slugged .512, and stole 19 bases, all on the way to winning National League Rookie of the Year honors in 1983.

Strawberry put up similar numbers over the next four seasons, including a 27-home run campaign in 1986 that coincided with the Mets’ first world championship since the miraculous year of 1969. He made the All-Star team each of those four seasons, as he would continue to do over the next four seasons, too. His career peaked in 1987 and ’88, when he posted OPS numbers of .981 and .911, respectively. In 1988, he led the National League in home runs and slugging percentage, and finished second in the MVP race, falling short to only Kirk Gibson, who actually had far inferior offensive numbers. By many measures, Strawberry seemed to deserve that MVP.

There were really only two shortcomings in Strawberry’s game. Despite a strong arm and excellent speed, he had a tendency to turn routine fly balls into misplays in the outfield. Offensively, he never hit for a particularly impressive batting average, reaching only as high as .284 in 1987, which made him something of a disappointment to those expecting another Ted Williams. In reality, Strawberry never had Williams’ ability as a hitter. Then again, who does? With a long swing and a tendency to strike out, Strawberry was never going to challenge for a batting title. His ability could be found in his power, his high slugging percentages, and his patience at the plate, which produced seasons in which he drew 97 and 85 walks at his best.

Like many New York stars, Strawberry could be controversial. In 1989, as the Mets players posted for the annual team picture, Strawberry tussled with team captain Keith Hernandez. Strawberry objected to standing next to Hernandez, saying, “I’d rather sit next to my real friends.” Hernandez responded by referring to Strawberry as “a baby.” As the two were separated by teammates, Strawberry yelled at Hernandez, “I’ve been tired of you for years!” That summer turned out to be Strawberry’s worst season in New York. He batted only .225, by far the lowest mark of his career.

There were other red flags. For a while Strawberry feuded with Mets second baseman Wally Backman, referring to him as “that little redneck.” At times, he publicly questioned his manager, Davey Johnson, never a tendency with a good end result. Strawberry’s biggest problem was his heavy involvement with cocaine and alcohol, which likely affected his play by the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Strawberry played better in 1990, a remarkable achievement given his off-the-field travails that season. Prior to the season, he underwent treatment in an alcohol rehabilitation center. He was also arrested on a weapons charge. To add to the list of transgressions, the courts ruled him guilty of tax evasion.

The array of personal problems and conflicts convinced the Mets to back off on any kind of aggressive attempt to resign Straw after the 1990 season. Instead, the Mets’ front office watched idly as the Dodges swooped in and sign him to a four-year free agent contract. Many observers criticized the Dodgers’ decision to sign Strawberry long-term in light of his personal failings.

Combating those critics, Strawberry played well in his first season with the Dodgers. He batted a respectable .265, hit 28 home runs, solidified right field for LA, and earned some votes in the MVP balloting. And then his career cratered. Wracked by back injuries, he played only a combined 75 games over the next two seasons. He clashed with manager Tommy Lasorda, who chided him for his lack of hustle and questionable work ethic. In April of 1994, Strawberry failed to show up for a game, a sign of a serious problem. Shortly thereafter, he entered the Betty Ford Center.

By the middle of 1994, the Dodgers did what was once considered unthinkable: They released the veteran star, receiving nothing in return for his services. They also swallowed the balance of Strawberry’s salary for 1994, a sign of just how much the Dodgers wanted him out of town.

For a player who once seemed destined for the Hall of Fame, the release underscored the general disappointment of Strawberry’s career. No one was predicting Cooperstown any longer for the onetime phenom. Undeterred, Strawberry soon found work with the Giants, but his career continued to flounder. The following spring, Strawberry received a 60-day suspension for illicit drug use. Fed up, the Giants released him that same day, putting his career firmly in the middle of the crossroads. At 32, Strawberry appeared to be done, at least in the minds of many major league officials.

Later in 1995, the New York Yankees developed a need for help in left field and at DH. Their owner, George Steinbrenner, also had a habit of signing name-brand veterans, and especially liked the idea of bringing a former Met into the Yankee fold. So on June 19, the Yankees made a controversial decision, signing Straw as a free agent. The signing drew criticism in some quarters, with some skeptics wondering why the Yankees would take a chance on a player with a history of drug abuse and a reputation as a clubhouse concern. Steinbrenner and Torre didn’t seem to care about the critics; they used Straw in a limited role, playing him only against right-handed pitching, and he did well. In 32 games, he put up an OPS of .812, while filling in as a left fielder, right fielder, and DH.

After the 1995 season, Strawberry found more trouble when he was charged with failing to make child support payments to his ex-wife. The story created embarrassment for him and the Yankees, upsetting Steinbrenner to the point that he released the veteran outfielder, only to resign him in July of 1996.

From 1996 to 1999, the Yankees continued to use Strawberry as a role player. Other than a lost 1997, a season in which he was saddled with injury, the veteran slugger proved highly productive for manager Joe Torre. He also battled back from a diagnosis of colon cancer, which occurred in early October of 1998 and prevented him from playing in the postseason, but he fought back to return to the playing field in 1999. As a supplemental player behind stars like Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, and Paul O’Neill, Strawberry fit in beautifully. Once questioned for a lackadaisical attitude, he became a likeable teammate and a strong veteran presence in the clubhouse. Along the way, he filled a key role as a background player for three world championship teams in 1996, ’98 and ’99.

Unfortunately, problems remained. After spending most of the 1999 season on leave, the latest punishment imposed by Major League Baseball, Strawberry rejoined the Yankees in September. Over the final month, he batted .327 with an OPS of 1.112. He then batted .333 in each of three consecutive postseason series, helping the Yankees win their second consecutive world championship. His performance gave every indication that he had plenty of talent left in the tank, but then came news of another failed drug test, this time resulting in a one-year suspension from baseball. That turned out to be the death knell for his career.

Sadly, the loss of his playing privileges left Strawberry more idle time to engage with drugs. He was arrested for driving under the influence, entered and then left a drug treatment center, relapsed repeatedly, and ultimately spent 11 months in prison on a variety of parole violations. At one point, he admitted that he lost his will to live, saying that he had stopped chemotherapy treatments because of ongoing depression.

In retrospect, it’s miraculous that Strawberry did not die, either from cancer or his repeated abuse of cocaine. His story could have ended in tragedy, his life lost in his early forties. But the story did not end there. Strawberry managed to earn his release from prison, leave drugs behind, and carve out a new career path. For that, Strawberry gives much of the credit to the example of his Hall of Fame teammate, Gary Carter. While Strawberry resisted Carter’s advice and example during his playing days, he came to realize that “The Kid” knew what he was talking about in terms of living clean, stressing the importance of family over the party scene, and making a place for religion in his life.

Strawberry and his third wife, Tracy, are now ordained ministers. In 2011, he established Strawberry Ministries, the headquarters for the spiritual mission run by him and his wife. Three years later, he co-founded a recovery center in Orlando, Fla. He has also done good work as a youth outreach spokesperson.

It has been 13 years since Strawberry used drugs and saw his life reach rock bottom in the form of cocaine and a prison cell. It has been 13 years since Strawberry reached a point where imminent tragedy, perhaps even death, seemed inevitable.

But as the world of baseball has seen so often, redemption is possible. A look at Strawberry’s 1992 card, where he is rounding the third base bag and heading for home, should remind us of just that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

Related Stories

Last Day in the Dugout

Sandberg to Host Otesaga Hotel Seniors Open Pro-Am

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Remembers Jim Bunning

Jim Bunning Throws His First No-Hitter

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

01.01.2023

Fans Cast Their Votes for Frick Award Ballot Candidates at Museum’s Facebook Page

01.01.2023

Yankees Slugger Alfonso Soriano Headed to Cooperstown for Hall of Fame Classic, May 23

01.01.2023