- Home

- Our Stories

- Hall call brings rightful honors for Dandridge

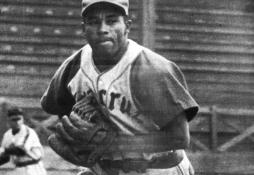

Hall call brings rightful honors for Dandridge

Ray Dandridge never got the chance to play in the American League or National League. But on March 3, 1987, that disappointment was finally soothed by the ultimate honor: Election to the Hall of Fame.

“I thought it would never come after so many others went in and I kept missing,” the 73-year-old Dandridge told the Associated Press after the Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee named him as their only electee to the Class of 1987. “I thought they had forgotten about me.”

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

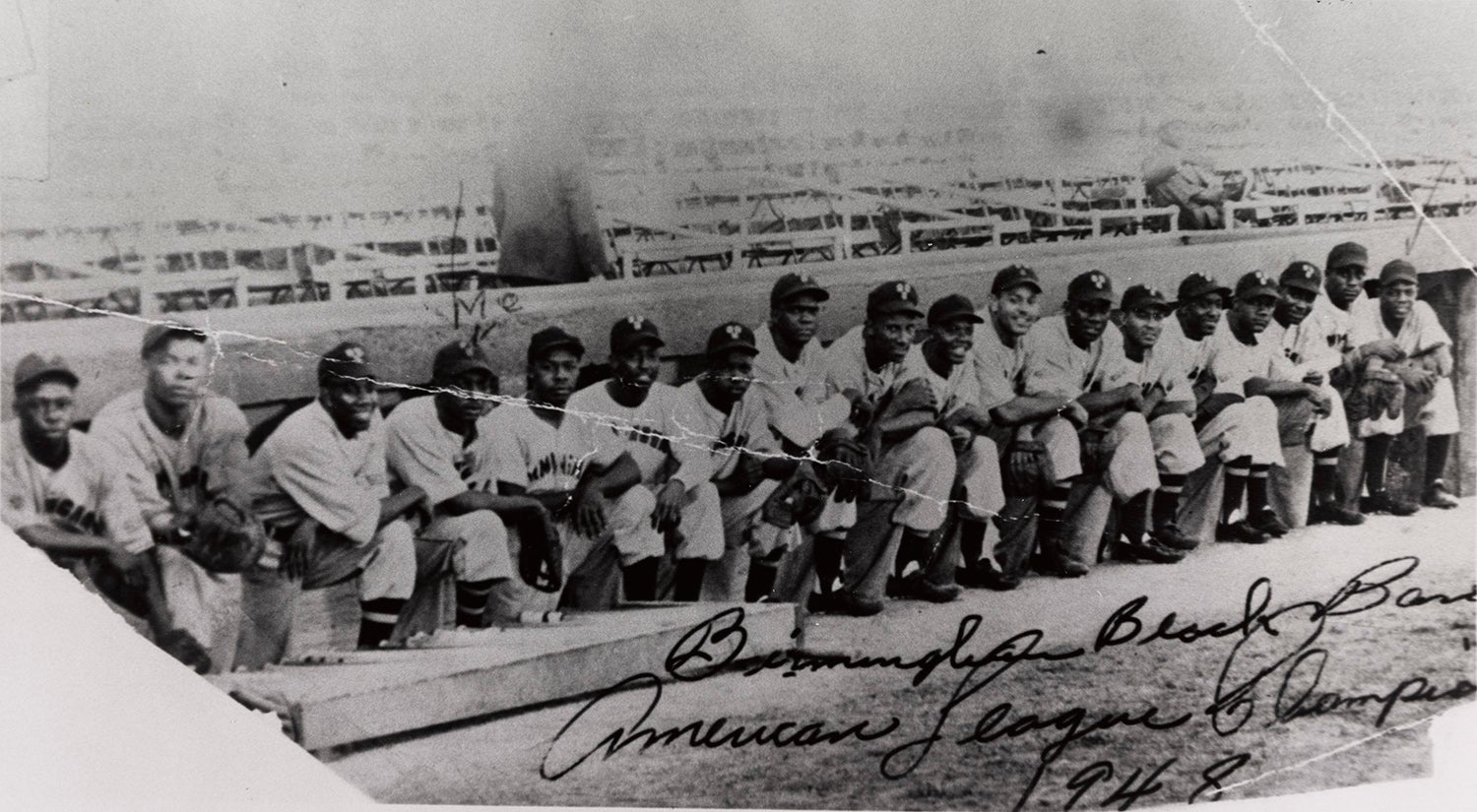

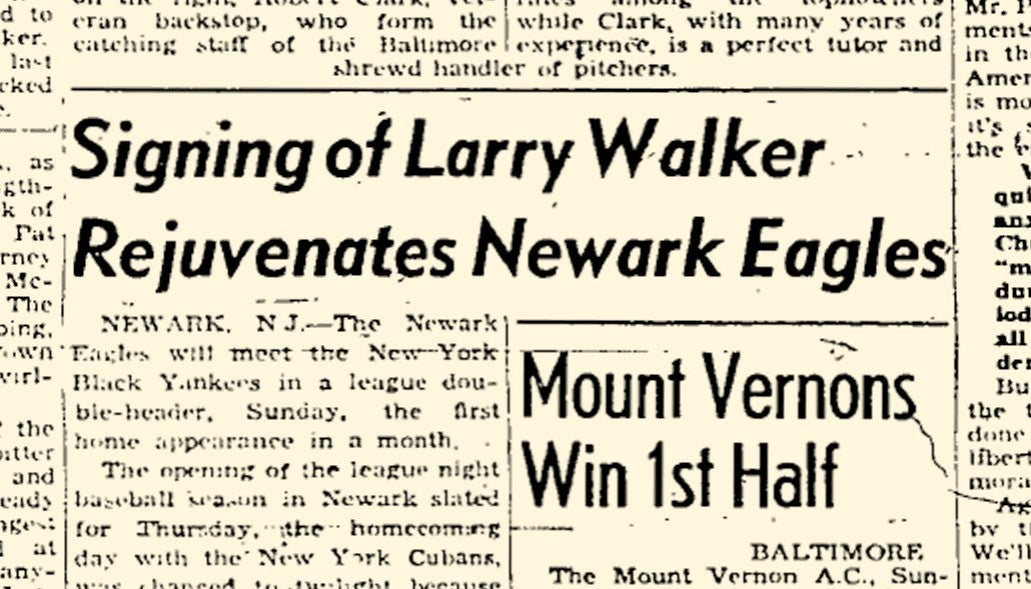

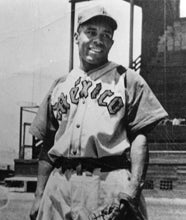

Dandridge, born Aug. 31, 1913, in Richmond, Va., starred in the Negro Leagues in the 1930s with the Newark Dodgers and Newark Eagles. A 5-foot-5 third baseman who excelled at the plate and in the field, Dandridge found opportunities and salaries were often better in the Mexican League – and throughout the 1940s moved regularly between the Negro National League and Mexico, playing for teams in Veracruz and Mexico City.

By 1947, Dandridge was in his mid-30s – but he was still attracting attention from AL and NL teams. But the timing never proved to be right, especially when Cleveland owner Bill Veeck offered Dandridge a chance to play in the American League.

“I was playing in Mexico then and they wouldn’t match what I was making there,” Dandridge told the AP. “I had to take care of my family.”

In 1949, Dandridge was signed by the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association – a top farm club of the New York Giants. Dandridge hit .362 in 99 games to earn Rookie of the Year honors and then followed that with a .311 average 11 homers, 80 RBI and 106 runs scored in 1950 to earn the American Association Most Valuable Player Award.

But even that wasn’t enough to convince the Giants to take a chance on Dandridge. Instead, he served as a mentor to a young Willie Mays in Minneapolis – and added to his legend with all those who saw him play.

“He was a natural third baseman because he was short, stocky and quick as a cat,” Monte Irvin, who was once Dandridge’s teammate on the Newark Eagles, told the AP. “You almost couldn’t hit the ball past him.”

Dandridge continued to play minor league ball into the mid-1950s before eventually retiring to Florida. Once he joined the ranks of the Hall of Famers, he relished his role and continued to honor the legacy of other Black baseball pioneers.

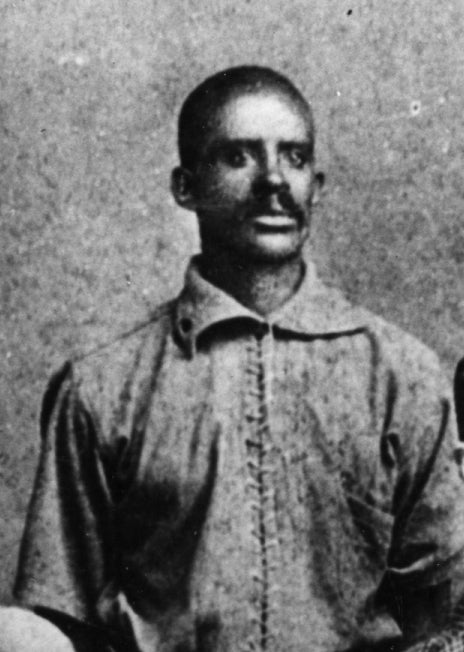

On the day before his Hall of Fame induction in 1987, Dandridge participated in a memorial service for 19th century star Bud Fowler in Frankfort, N.Y., where a new grave marker was installed. Thirty-five years later, Fowler joined Dandridge as a Hall of Famer.

“I’m thankful I’ll be able to see the Hall of Fame,” Dandridge told the Associated Press on the eve of the 1987 Induction Ceremony. “I always wanted to say I came out of the cornfields and got to the major leagues. That was my biggest dream. But now I can say I came out of the cornfields and got to the Hall of Fame.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum