- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Waite Hoyt Remembers The Babe

#Shortstops: Waite Hoyt Remembers The Babe

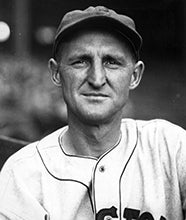

Waite Hoyt had a remarkable life in baseball. He signed with the New York Giants as a 15-year old high school student, earning the nickname “Schoolboy.” He appeared briefly with the Giants as a baby-faced 18-year old in 1918, then pitched in the big leagues for the next 20 years.

He earned his place in the Hall of Fame on the strength of his 10 years with the Yankees, where he was an instrumental part of the 1920s Bronx Bombers dynasty. He played in six World Series, winning three championships (he appeared in another later with the Athletics). He was probably the most important pitcher on the powerhouse 1927 Yankees when he led the American League in wins (with 22) and all of baseball with a .759 winning percentage. He was even better the next year, winning 23 games against 7 losses while also leading the league in the yet-to-be-invented statistic of saves, with eight.

Five months after retiring as a player 1938, he hosted his first regular radio show, doing 15-minute sports wraps. After providing color commentary for Red Barber and the Dodgers, he was hired by Cincinnati Reds, where he did play-by-play for 24 years and more than 4,000 games. If he wasn’t as polished as some announcers, he made up for it in his sincerity and deep knowledge of the game. Listeners would look forward to rain delays when Hoyt would tell stories. And one of his favorite subjects, always, was Babe Ruth, a former teammate in both Boston and New York.

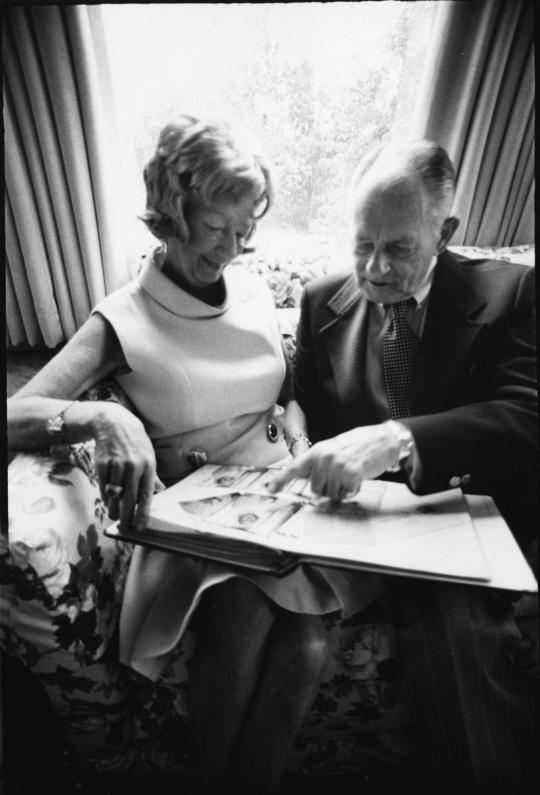

In 1981, over the course of two days in October, for nearly six hours, Hoyt, then 82 years old, recalled some of those stories in an interview for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Recorded on cassette tapes, the oral history was recently digitized as part of the Digital Archives Project.

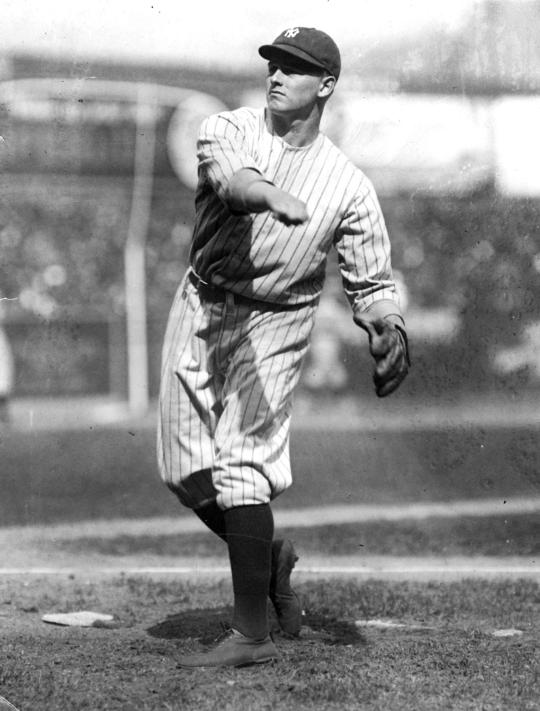

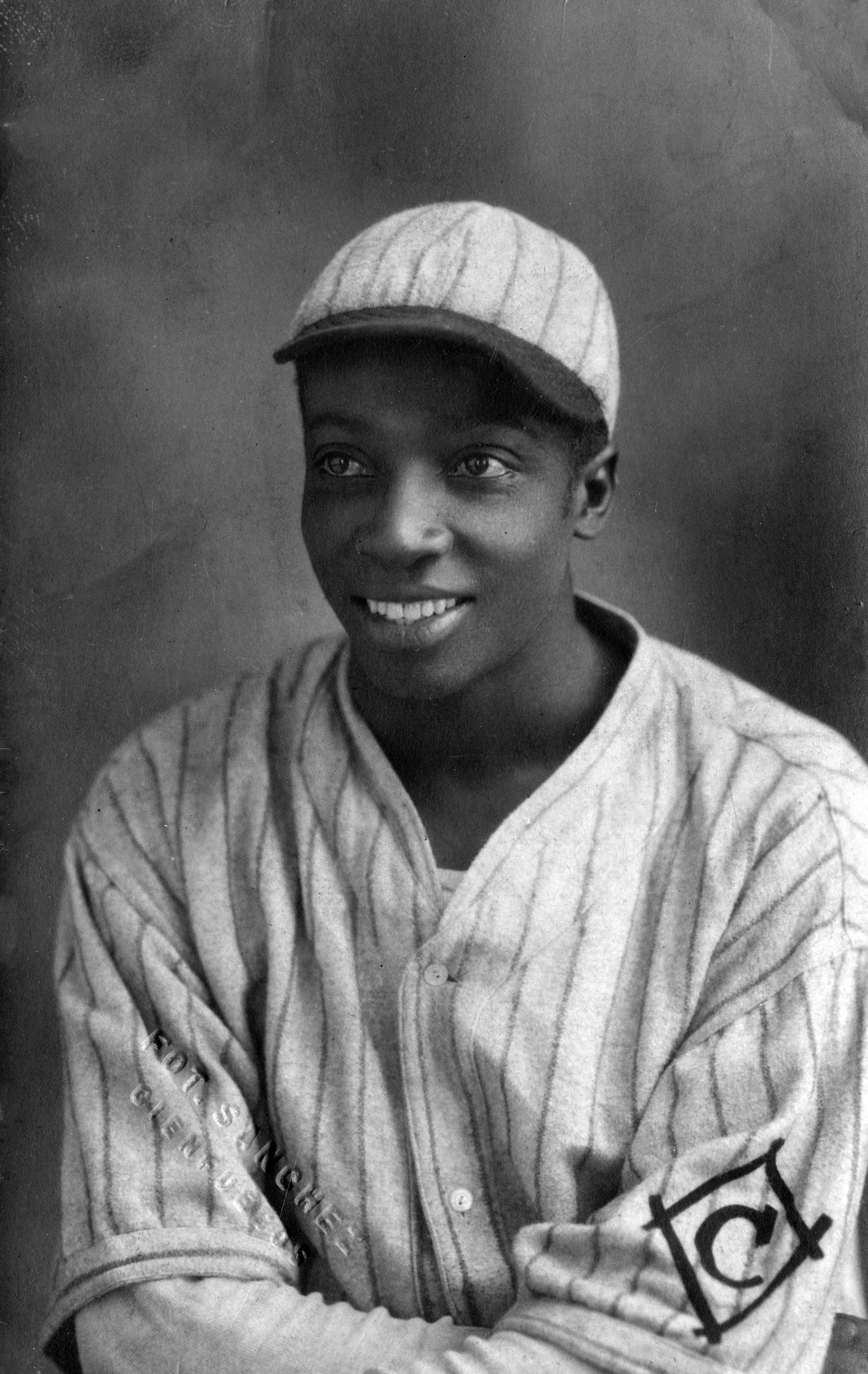

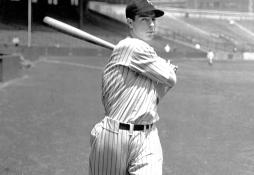

Drafted as a 15-year old, Waite “Schoolboy” Hoyt made his Major League debut at 18 at the end of the 1918 season, the same year this photo was taken. Hoyt-Waite-2452-86_HS (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

“I could tell stories about that guy all day long,” Hoyt says, and then he talks about Ruth for nearly an hour. First on his agenda – in a voice that is loud, definitive, and about as agitated as Hoyt sounds on the tapes – was to clear up some popular misconceptions:

To begin with, let me tell you this about Babe Ruth. He was not fat. And he did not have skinny legs. He had rather tapered ankles, that’s true. But . . . the calves of his legs were very good sized, and he was not fat. He had a big chest and he had a very small fanny and he was not big around the waist.

He was not a drunk, by no chance. He drank, and I guess at times he was drunk, but he was never, never was he, did he miss a game because of that or have a bad day because of it, never. Never. Never. Any of these lame-brains that write and talk on the air about fat, drunk Babe Ruth, that’s silly and ridiculous.

Apologizing in advance for being “so frank,” he confesses that “we used to compare him to an Airedale or a dog or a sheep hound or something.” He’d go out “carousing” all night, “visiting his girlfriends,” then come home to a “very respectable family, and the family would pat the dog on his head and say, ‘What a nice dog Rover is.’ Ruth was like that.”

Hoyt tells of a time the Yankees played in Detroit on Harry Heilmann Day, when Heilmann was presented with a number of gifts, including a Great Dane (“jeez, a beautiful animal”), but Heilmann didn’t know what to do with it. “So he sent the clubhouse boy over, and the clubhouse boy said [to Ruth], ‘Mr. Heilmann wants to know if you’d like to have that dog.’ And Babe says, ‘What kind of dog is it?’ The kid says, ‘A Great Dane.’ And Ruth says, ‘Well, if it’s a great dame, I’ll take it!’”

Hoyt doesn't gloss over Ruth's faults. He admits that Ruth “did not know the social graces.” He recalls a time when Hoyt was pitching and a fly ball was hit to Ruth in right field. Hoyt says it looked like Ruth “short-legged it, meaning he didn’t take long strides, and pulled up short, and the ball fell for a base hit.” Hoyt stood on the mound, shaking his head, hands on his hips, glaring at Ruth. After the inning, Ruth stormed into the dugout: “Don’t you ever show me up again.”

Hoyt was pulled from the game and had just finished showering when the game ended. “I was sitting on my bench in front of my locker without any clothes on” and Ruth comes up to him and calls him names and says, “I’ll punch you in the nose.” Hoyt snapped back, “’Well, you’re not tied.’ So he took a kick at me, with his spikes on, and he’s in full uniform.” Hoyt jumped up and they exchanged blows, teammates trying to pull them apart, with tiny Miller Huggins, all 5-foot-6 and 140 pounds, climbing between the two men to break it up (and not without suffering a few blows himself). Then, with a voice more quiet, sounding humbled, maybe embarrassed, Hoyt says “But Ruth, after that, he and I didn’t speak for a couple of years.”

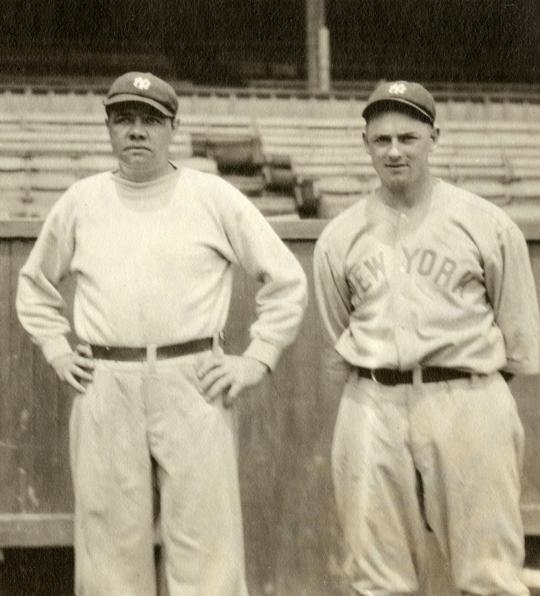

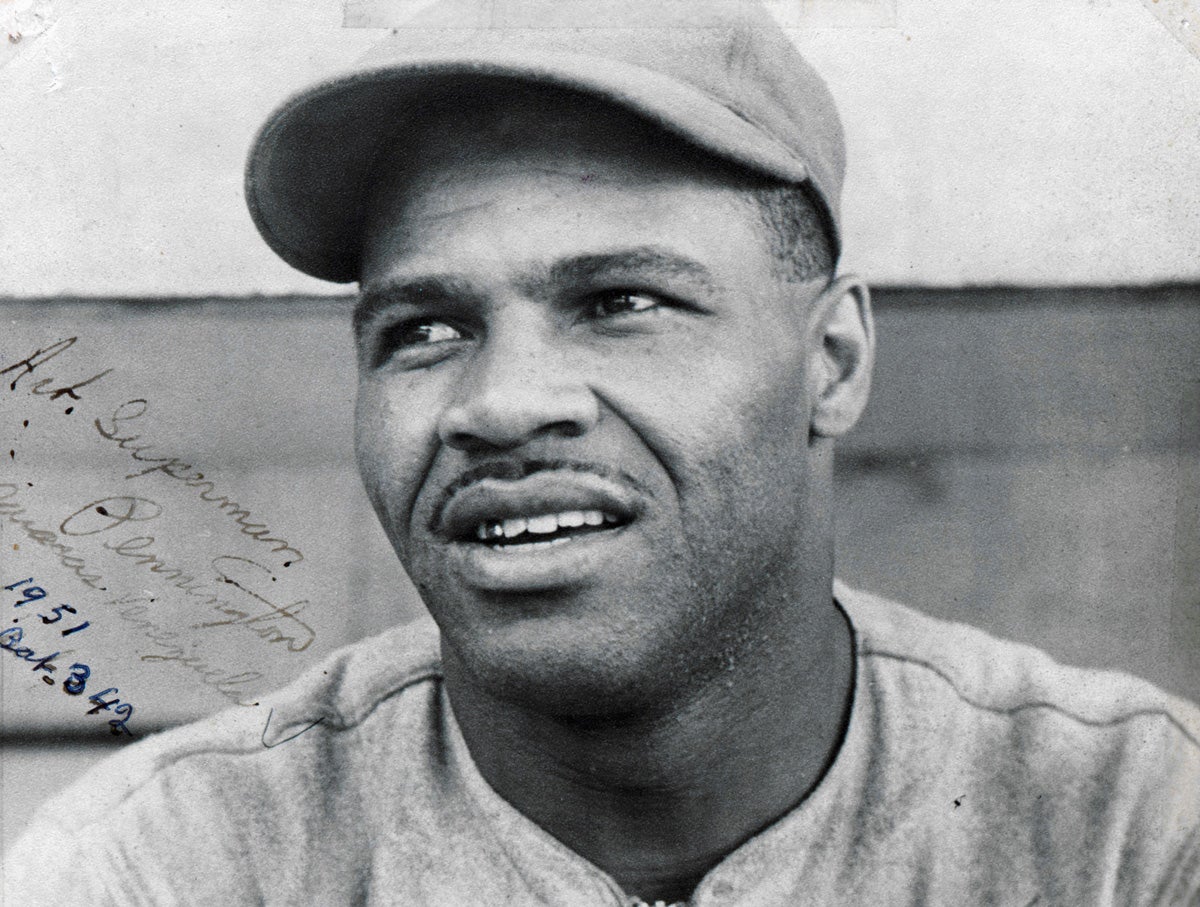

Waite Hoyt and Babe Ruth were teammates for ten years, including nine with the Yankees' dynasty in the 1920s (image cropped). BL-4122-91 (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

In St. Louis, whenever the team's train left town, Ruth would arrange to have one of the women’s restrooms on their Pullman car converted into a kind of saloon. There would be some home brew “plus about 15 or 20 racks of spare ribs. . . . He would set up shop and he’d charge 50 cents for all the beer you could drink and all the ribs you could eat.” Hoyt walked by the open door of Ruth’s make-shift bar during one of these train rides of out St. Louis, and muttered, “No, no” he didn’t want any. But for Ruth, it had gone on for too long. “Ah, come on,” Ruth said. “Let’s forget this. This is ridiculous.” They made peace over beer and ribs on the rattling train home.

“Ruth was a very good guy,” Hoyt says, as if lost in memory. He remembers a time when the Yankees had a meeting on potential World Series shares. Some didn’t want to give a player who had been on the team only a couple of months a full share if they won. Ruth stood up and said if the guy didn’t get a full share, he would sit out the Series. There was no further discussion.

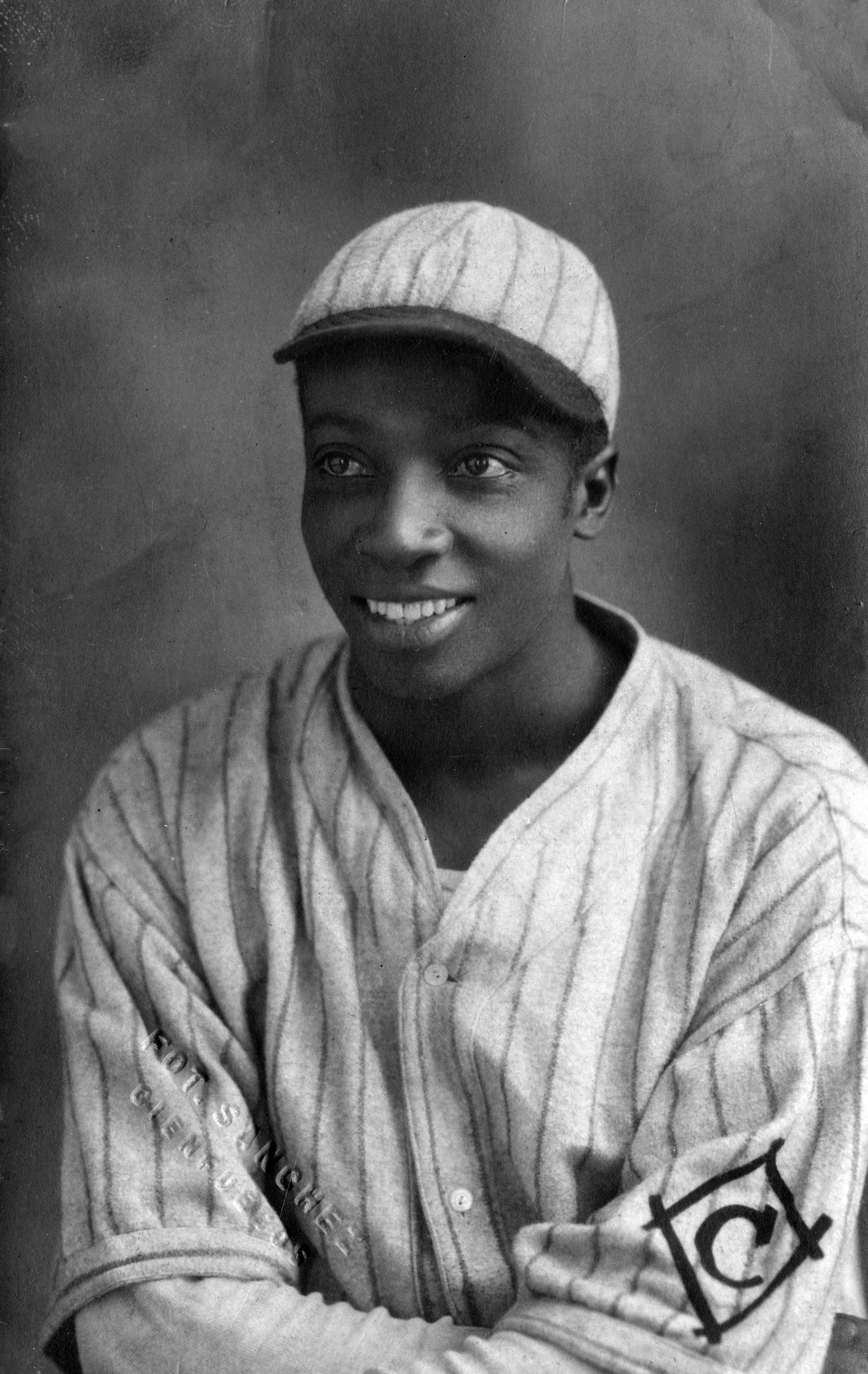

He mentions Ruth’s warmth with fans, his philanthropic work, his love of children, his generosity with teammates (filling his bathtub with ice and beer and hosting after-game parties in a red robe with a velvet collar and in red Moroccan slippers), repeating that Ruth “was a good guy.”

Hoyt becomes serious and somber for a moment, describing his own religious beliefs – his belief in “a power greater than ourselves, God, or destiny, or whatever you care to call it. . . . If there is a Judgement Day,” Hoyt says, “I believe that Ruth will receive more pluses than minuses.” He concludes with a story to illustrate, he says, “how Ruth was, at the bottom of his heart.”

It was in the winter of 1947-1948, a cold day, when “Mrs. Hoyt” and Waite Hoyt went to visit Ruth in his hotel suite, where Ruth was dying from cancer. Ruth, he says, was on the sofa, “slumped low with his head almost below his knees. He had a glass of beer on the table,” one of the only things he could keep down. They visited, talking mostly with Ruth’s wife, Claire, because Babe was so sick “he could hardly talk.” After an hour or so, the Hoyts said they needed to get going. As they rose, Ruth stirred. He struggled to lift himself out of the sofa. Hoyt describes the rest:

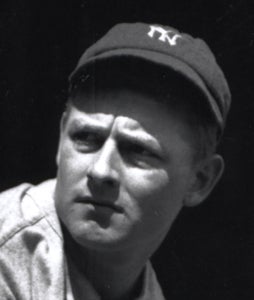

Babe Ruth loved children, one of many qualities, or “pluses,” that Hoyt saw in Ruth. Ruth-Babe-5641.95_w-kids_-NBL (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Share this image:

So he said, “Hey, wait a minute, doll” to Mrs. Hoyt. He said, “Hey, wait a minute,” he said. ‘I’ve never known you,” he said. “I’ve never given you anything either,’ he said. So, he went into the kitchen . . . . and he opened the refrigerator door and there were two orchids in there. And he came out with the orchids and he gave them to Mrs. Hoyt and he said, “Here,” he said. “Do me a favor,” he said. “Don’t forget the old Babe, will ya?”

Larry Brunt is the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. To support the Hall of Fame Digital Archive Project, please visit www.baseballhall.org/DAP

More #Shortstops

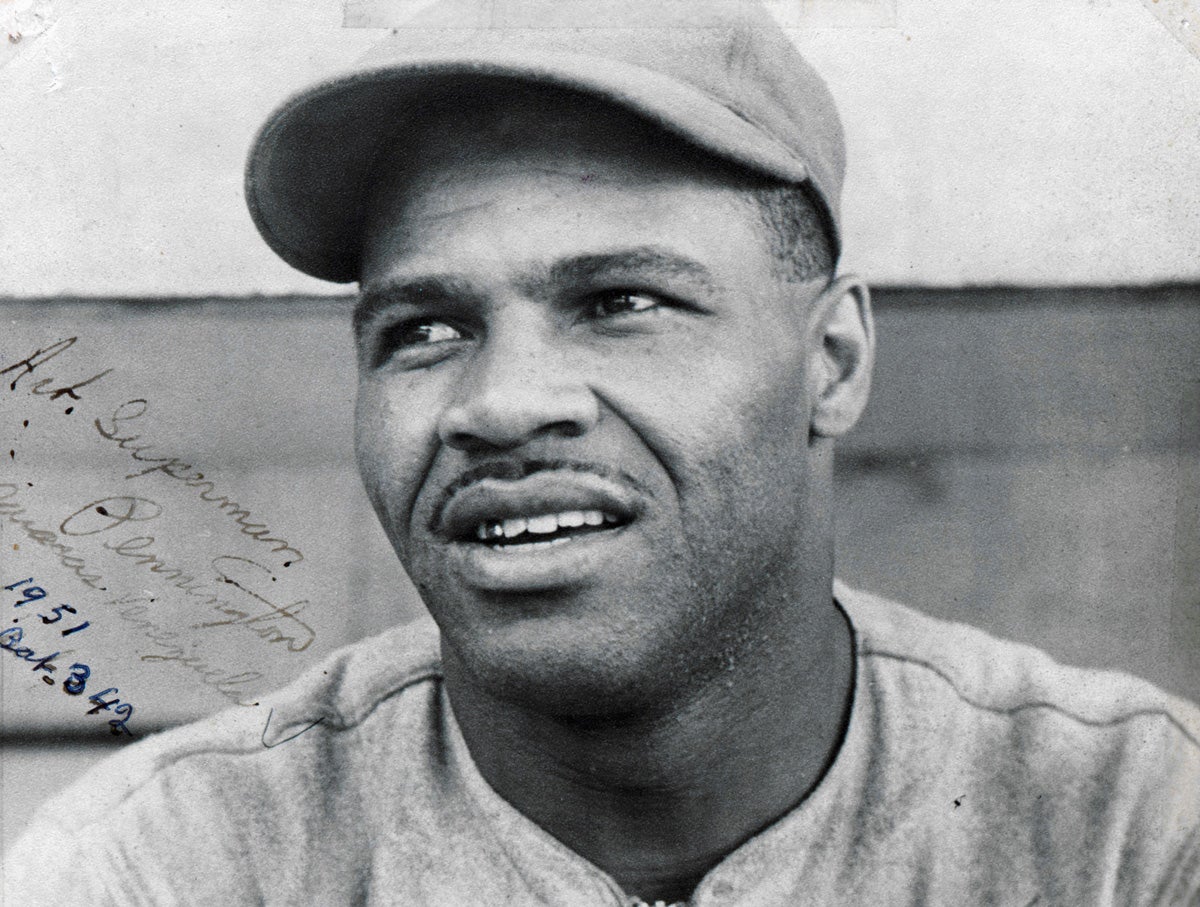

#Shortstops: Art Pennington: An Equal among Greats

Christy Mathewson: The First Face of Baseball

Fast feet, Cool shoes

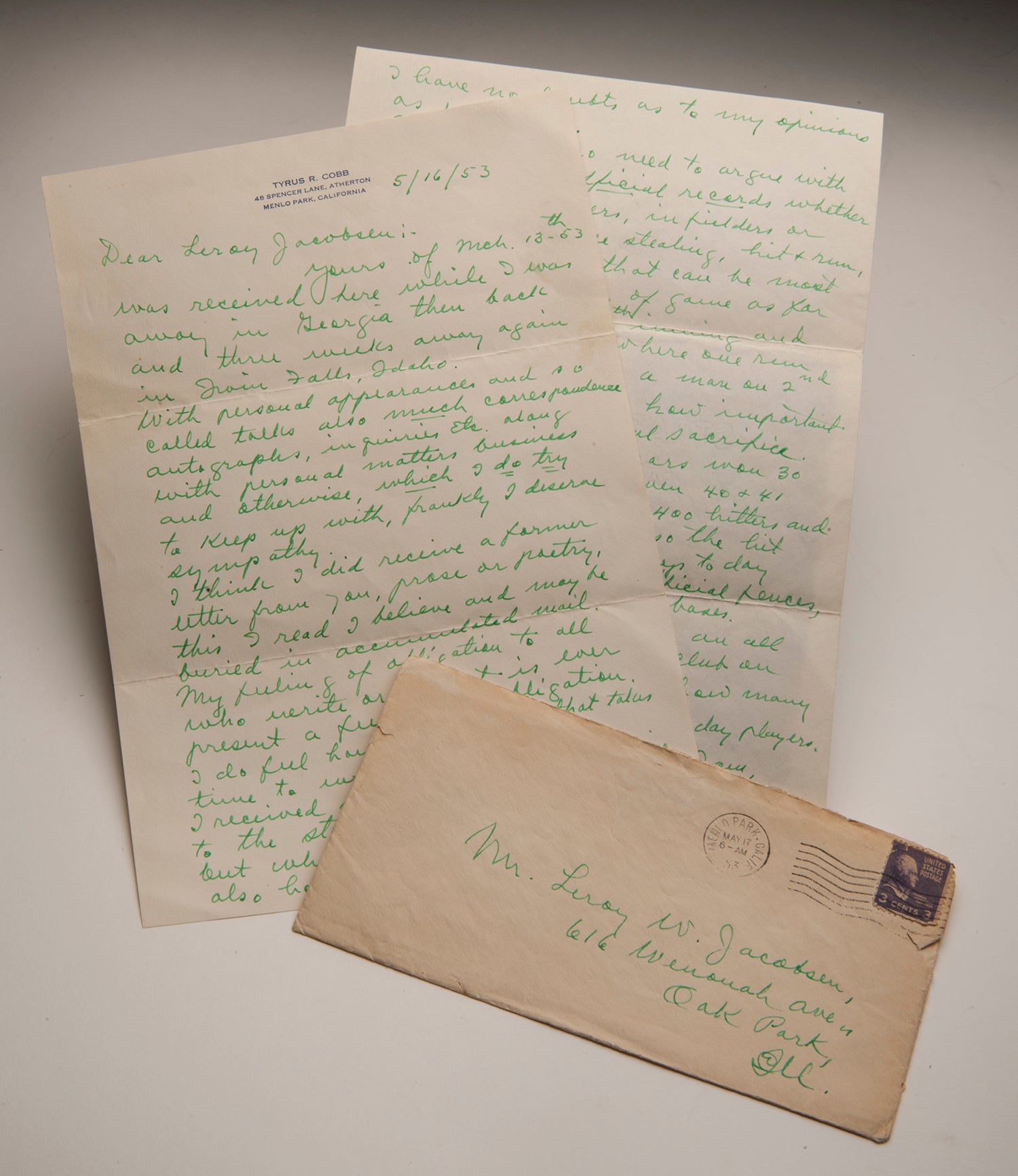

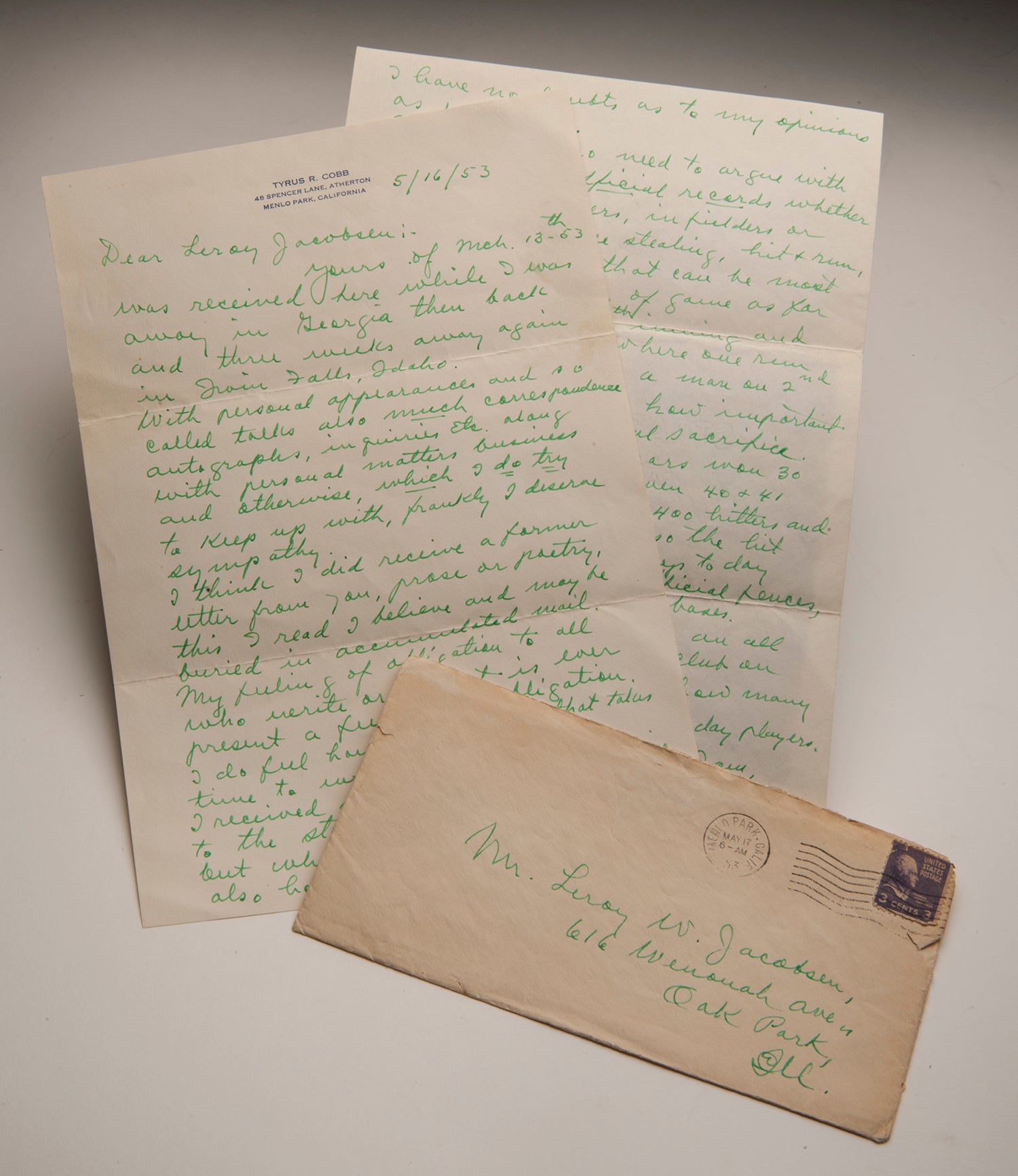

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb

#Shortstops: Art Pennington: An Equal among Greats

Christy Mathewson: The First Face of Baseball

Fast feet, Cool shoes

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb

Related Stories

Albert Belle’s numbers earn him a place on Today’s Game Era ballot

Remembering Joe Garagiola

Baseball and the Funny Papers

Juan Marichal makes his final MLB start with the Los Angeles Dodgers

1943 Hall of Fame Game

'Fastball' Headlines Tenth Annual Baseball Film Festival

Rickey Henderson’s two RBI lead A’s to 11th straight win to start 1981 season

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Bob Bailey

Domination in the Dome: Nolan Ryan throws his fifth no-hitter

Spaceman Headlines 11th Annual Baseball Hall of Fame Film Festival Sept. 23-25 in Cooperstown

Pre-Integration Era Committee Ballot to Be Considered Dec. 7 at Baseball’s Winter Meetings

01.01.2023

Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk Featured in Nov. 7 Voices of the Game event as Museum Unveils Whole New Ballgame Exhibit

01.01.2023

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

01.01.2023

Baseball Writers’ Association of America Election Results Revealed Wednesday, Jan. 18

01.01.2023